|

Larinum

In Roman times, Larinum (today Larino) was a thriving and large settlement of ancient origin, located in the hills of the hinterland at an altitude of about 400 m, not far (about 26 km) from the coast of the Adriatic Sea, of considerable importance due to its strategic location: it stretched over a large, fertile and flat area (today's Piana San Leonardo), in a strategic position, overlooking the valley floor and the lower course of the Biferno river, and it was also an important road junction, as it was located at the convergence of important road axes, which allowed profitable trade exchanges.[1] These particular geographical features, together with the favourable climate and the fertility of the soil, which was easy to cultivate, explain the prosperity and economic development of Larinum, which already reached its peak in the 3rd century BC. This made it a frontier town and a crossroads of cultures, between the Adriatic coast and the inland area of Samnium, always open to the influences of different cultural environments, as confirmed by the archaeological remains, which attest to the existence of a rich and populous town even before the Punic Wars.[2] The territoryThe city was located along the so-called via litoranea (also mentioned by Livy), an ancient road that from the north descended along the Adriatic to Histonium (Vasto) and then, by an inland route, after passing Larino, proceeded eastward to Sipontum (Manfredonia) and continued, again along the coast, to Brindisi;[3] this great artery of communication was called Traiana Frentana, an appellation derived from a sepulchral inscription of a certain Marco Blavio, who was one of the curatores of the road connecting Ancona to Brindisi.[4] Moreover, Larinum, through the Biferno valley floor, easily connected with the inland area of Pentrian Samnium, in the direction of Bovianum (Bojano), and by grafting onto the route of the Celano-Foggia sheep-track easily entered into communication with northern Daunia, in the direction of Luceria (Lucera). This dense network of routes defined, therefore, an extensive territory, a crossroads of cultures of various origins, a land of passages and settlements, but always in relationship with neighboring peoples, in a mutual relationship of cultural exchange.[5] The geomorphological investigations carried out in the territory of Larino have shown how this territory has proven, since time immemorial, to be propitious both for the choice of inhabited settlements and for the construction of roadways. In fact, the reserves of clay and, to a lesser extent, limestone, present locally, suitable for exploitation in the furnaces, facilitated in ancient times the construction of masonry works, together with the presence of abundant river stones, easily available due to the proximity of the Cigno and Biferno rivers.[6] Moreover, the territorial framework of the ancient Frentania, to which Larino belonged, represented the least impervious area of the entire Samnium, since it included the hilly strip (about 30 km. wide), easily passable, sloping toward the Adriatic Sea, consisting of arenaceous and clayey soils that were drained to the narrow, flat coastline. Encompassed between the Sangro, to the north, and the Fortore,[7] to the south, the Frentanian region was rich in rivers from the inland Apennine areas (Sangro, Trigno, Biferno, Fortore) and minor watercourses (Foro, Osento, Sinello, Cigno, Saccione, Tona), whose valleys represented natural and easy communication routes between the coast and the interior. In addition to the main road system, the area was also served by a series of secondary routes, which constituted a dense network of communications, into which large and small settlements were inserted, able to connect with each other easily. It is assumed that the river courses themselves were used as easy routes between the coast and inland areas, since some ancient sources (Livy, Pliny), in defining portuosum flumen both the Trigno and the Fortore, suggest the existence of port activities in that stretch of the Adriatic coast.[5] Therefore, the morphological configuration, the abundance of water, the decidedly mild climate, the presence of a widespread forest vegetation on the hills, and the wide network of sheep-tracks, running parallel to the coast, favored the life and economy of the local populations in pre-Roman times, encouraging forms of settlement and organization of the territory.[8] Larinum is currently an archaeological site in the province of Campobasso, Molise, Italy. In 2016, the archaeological area had 1,566 visitors.[9] Admission is free. HistoryA systematic archaeological exploration of Samnium is a relatively recent initiative, as it was started in the early 1970s and gradually increased in the following decades. The earliest records of collections of prehistoric material of various Molisian provenance are available through surface surveys carried out beginning in 1876 by anthropologist Giustiniano Nicolucci and palethnologist Luigi Pigorini. The latter wrote in that very year complaining of a great poverty of information about the Stone Age in the province of Molise. It consists of eight knives from Larino, a scraper and two knives from Casacalenda and a knife from Montorio nei Frentani. Currently, the material found is partly preserved at the Luigi Pigorini National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum in Rome and partly at the Anthropological Museum of the University of Naples Federico II.[10][11] Subsequently, it was to the credit of the British mission of the University of Sheffield and the team led by archaeologist Graeme Barker, to have conducted a capillary surface reconnaissance, started in 1974, along the wide strip of territory (Pentrian and Frentanian) that constitutes the Biferno Valley (The Biferno Valley Survey), which from the Matese massif reaches the sea, following the course of the Tifernus. Systematic land sampling has led to the identification of about one hundred and twenty ancient settlements of various sizes, covering a period from the Neolithic to the first century B.C. Barker's analysis of the results of the survey offers a picture of an intense peopling of the Frentanian territory gravitating on the lower Biferno valley, where 60 percent of the identified inhabited settlements turn out to be located. Settlement choices seem to be dictated not only by the need to exploit the sites most favorable to cultivation, but also by the intention to keep close to natural communication routes.[12] Through Barker's survey, the main information on the nature of early Neolithic settlements located along the Biferno valley is available, particularly of the most substantial one identified on Monte Maulo (about 350 m a.s.l.), a vast plateau below Larino, overlooking the lower Biferno valley, at the edge of a promontory about 20 km. from the sea as the crow flies. Inspection of the site, explored in 1978, led to the discovery of several species of mollusks and snails; 146 charred seeds were recovered, mainly cereals (barley and wheat) and legumes, and numerous samples of animal bones (cattle, sheep and pigs), mostly slaughtered. The excavation conducted at the top of the slope, among the plowed soil, recovered about 1,500 sherds of common pottery, mostly decorated, and about 200 pieces of chipped flint, almost all of a local stone of poor quality. Radiocarbon dates, obtained in an Oxford laboratory, date from the second half of the fifth millennium BCE. Thus, the botanical and faunal records appearing in the area confirm that early agricultural communities were present in the lower Biferno Valley as early as the late fifth millennium B.C.[13] The site has also yielded traces of human habitation, consisting of a series of circular holes, probably dug to recover flint, filled with ceramic fragments, and structural remains of Neolithic huts (pressed clay with branch imprints). The data from Monte Maulo make it possible to reconstruct the paleoenvironment of this small part of Molise; they confirm that as early as the Early Neolithic period a mixed economy of gathering and farming was in force, with prevalence of the latter, given the variety of botanical remains found, both cereals (spelt, barley, common oats, millet, soft wheat) and legumes (broad beans, peas, lentils), as well as the numerous faunal remains, relating to animals raised, slaughtered and consumed on site. Between 1969 and 1989, an accurate study conducted by Eugenio De Felice on the settlement of Larinum and the territory surrounding the ancient Frentanian center further enriched what is known about the early phases of occupation of this area. It has thus been possible to identify a number of Neolithic Age agricultural villages distributed throughout the territory, thanks to the numerous finds of ceramic fragments and remains of lithic industry, settlements mostly located on hilly heights and near water sources. Ceramic and bronze material, referable to the late Bronze Age - early Iron Age, has been found in various places at Montarone and Guardiola, two heights bordering to the south and north the ancient settlement of Larino, suitable for the settlement of humans and animals, well connected to both the Biferno valley floor and the coastal plain.[14] Although of very ancient origin, as evidenced by sporadic finds dating from the Final Bronze Age and the early Iron Age, the first significant evidence of living contexts of the city of Larino starts from the fifth century B.C.; these are mostly burial cores, often not even perfectly intact, since, due to building expansion and massive earthworks carried out for the construction of the railroad, much has been destroyed and very little remains to be explored. Even the evidence of the Roman phase, the one best known, is currently in an extremely fragmentary state. Also of particular interest for the reconstruction of Larinum's history are the coins and epigraphic texts that have been found, references that are also useful for an understanding of the scant archaeological evidence recovered in the different areas of its urban fabric. However, these data significantly reveal continuity of life in the area as far back as protohistoric times.[15] From the very beginning, in 1977, the first archaeological investigation tests, initially carried out by the Soprintendenza Beni Archeologici del Molise along the southern slopes of Monte Arcano (about 2 km northwest of Piana San Leonardo), on the hills facing north, ascertained the presence of an archaic necropolis, dating back to the 6th century BCE. B.C. with rectangular burial graves, with mound covers of limestone chippings; the vessel trove almost constantly includes the large olla, bucchero, and clay pottery vessels coarsely imitating Daunian forms. Explorations conducted in other areas as well have revealed, albeit fragmentarily, the presence of a settlement stratification of ancient origin throughout the Larinum countryside, covering a rather wide time span. However, over the years it has only been possible to carry out explorations limited to the areas that remained free of construction, the entire area having by then been abundantly urbanized since the post-war period.[16] Subsequent archaeological investigations, extended to other municipalities close to the Molise coastal area, found similar presence of burial nuclei, of considerable size, dating back to the pre-Roman historical phase, in the centers of Termoli, Guglionesi, Montorio nei Frentani and Campomarino. In the latter center, in the locality of Arcora, excavations carried out since 1983 have unearthed substantial traces of a protohistoric village, dating between the Final Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age (9th-7th centuries B.C. ), which extended, over an area of about four hectares, along the ridge facing the Adriatic coast, naturally defended on two sides by steep walls; the flat area inland showed clear traces of defense and enclosure structures (wall, palisade and moat). Surface reconnaissance attests to a continuous occupation of the site up to the entire fifth century B.C.[17] In addition to partial ruins of living structures, the site has yielded conspicuous traces of human activities: numerous artifacts of ceramic material, vessels and containers for cooking and storing foodstuffs, utensils and objects of domestic use, hearths and stoves. Numerous bone remains of animals, both domestic (cattle and pigs) and wild (deer and fox), with obvious traces of slaughtering. The amount of seeds recovered during the excavation, both legumes and grains, was remarkable. A community, then, with a simple social organization, living on agriculture, animal husbandry, hunting and gathering wild fruits, as part of a household-based subsistence economy.[18] Traces of other settlements have been found to the north and south of the Arcora area: it seems clear, therefore, that the Adriatic coast, from the Biferno to the Fortore, was occupied by settlements that exploited the natural platforms separated from the coast by steep and craggy ridges. This evidence from lower Molise documents the existence of numerous scattered settlements, not large, distributed over a fairly wide area and consisting of communities mainly with an agricultural and pastoral vocation. Still in this area the centuries between the 6th and 4th B.C. are known mainly thanks to the conspicuous archaeological documentation from the numerous necropolises, which show a dense occupation of the territory. The grave goods and personal ornaments of the deceased testify to cultural differentiations between the different centers: for example, the coastal settlements show aspects predominantly akin to the Daunian culture; on the contrary, Larino, a frontier town, also has a part in Western culture, coming from the Pentrian and Campanian areas, as shown by the presence in some burials of bucchero pottery, which is completely absent in the contemporary necropolis of Termoli.[19] In funerary ritual, on the other hand, the entire Frentanian area shows substantial cultural unity, which differentiates it from Daunia, where, for example, the deceased is habitually laid in a crouched position, on his side, and not supine. But beyond this single difference, there is cultural uniformity and substantial continuity between the two areas: between Daunia and Frentania, therefore, the Gargano promontory does not constitute a dividing line; between the Tavoliere and the Molise coast there is an undeniable continuity.[20] Monetary finds, moreover, also confirm the picture of Larino as a city open to Apulian influences and at the same time important for its connections with inland Samnium: for this reason, even from ancient sources, there was already a certain difficulty in framing Larino in one precise cultural sphere rather than another. Among the various bronze issues, for example, some follow the Greek weight system, in use in the Campanian and Samnite mints, while others, more recent, follow the Italic system, with decimal fractionation, typical of the Adriatic areas.[21] In the necropolises of lower Molise, in the Archaic period, burials habitually involved the inhumation of the deceased, in a supine position, in pits dug in the clay layer and filled with limestone chippings. It is likely that these stone mounds outcropped from the ancient ground level, marking the location of the grave. The grave goods, laid at the feet of the buried person in a specially made space, usually consisted of small ceramic objects (cups, amphorae, bowls and mugs); metal vessels were rare. In female burials there are objects of personal adornment (fibulae, necklaces, beads, pendants, rings), in male burials weapons and utensils (iron knives, razors and spear or javelin cusps).[22] Bronze helmets have also been found sporadically, some of the Picenian type, others of the Appulo-Corinthian type, which evidently served to highlight the social rank of the deceased. The grave goods of Frentanian burials from the 6th-5th centuries B.C.E. are usually richer in material than those of the contemporary ones from the inland areas of Samnium. They prove to be mostly uniform in the type of materials deposited. Italic periodLarinum urbs princeps Frentanorum reads an ancient tombstone, underscoring the important role played in the past by this flourishing city of lower Molise, which was one of the main centers of the Frentanian territory. According to historian Giovanni Andrea Tria, as the centuries passed, the name underwent numerous changes and was deformed into Alarino, Larina, Laurino, Arino, Lauriano, until it reached the definitive toponym of Larinum in Roman times.[23] According to an ancient tradition, taken up by historian Alberto Magliano, its foundation would most likely date back to around the 12th century B.C. at the hands of the Etruscans, in the course of their immigrations to the fertile plains of Apulia; the city's first name would have been Frenter, as inferred from some coins found in the Larinese countryside.[24] The hypothesis has even been advanced that the people who inhabited ancient Larinum were descendants of the ancient Liburnians, who came from the coast of present-day Dalmatia, either via the Adriatic Sea or by land migrations at the end of the Bronze Age.[25] One of the most reliable theses is that the Samnites descended from the Sabines, also in view of the etymological connection between Safinim, Sabinus, Sabellus, Samnis, Samnitis, which can be traced back to a common Indo-European root.[26] In fact, one of the most debated points in the history of Samnium in recent years is the one concerning the ethnogenesis of the Samnites, already the subject of various conjectures by the ancients in the past. According to the most recent research in historical linguistics, Osco-Umbrian populations, having left the steppes of central and eastern Europe and crossed the Alps, penetrated the Italic peninsula in the second half of the second millennium B.C., settled along the central Apennine ridge, pushing even southward along the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian coasts and overlapping with the indigenous peoples. Later, as Strabo (V, 4, 12) narrates, another Indo-European population, the Samnites, akin in language and religion to the Oscans, would immigrate to the central southern area of the peninsula, to the point that the two groups would eventually coincide and overlap, albeit with varied tribal differentiation. Both Greek and Roman sources identify the tribes of the Carecini, Caudini, Irpini, Pentri and Frentani in Samnium, emphasizing that all were fierce adversaries of Rome, although they provide little information on the differences between them.[27] It is impossible to know with certainty where these peoples came from, how numerous and different from each other they were, and in how many waves they arrived. It is known with certainty, however, on the basis of abundant archaeological evidence, that as early as the second half of the eighth century B.C. these peoples were permanently settled in what would historically be Samnite territory. Inscriptions and epigraphic records testify that as early as the 6th century B.C. central-southern Italy, south of the Liri and Sangro rivers, was inhabited by populations traditionally defined as Italic-speaking, with the exclusion of Latium, Latin-speaking, and Apulia, Messapic-speaking. Oscan-speaking (Samnium, Campania, Lucania, and Bruzio), Umbrian-speaking (in the territories of Gubbio, Assisi, and Todi), and Sabellian-speaking (including Vestini, Marrucini, Peligni, Equi, Marsi, Volsci, and Sabini), closely related populations were distinguished. This situation reflected the progressive chronological stratification of different, but in many ways also related, cultural and linguistic entities.[28] As early as the 4th century B.C. dialectal variations had become entirely negligible. Most likely the name "Oscan" was given to the language of the Samnites precisely because the language of the invaders was very similar to that of the Oscans whose lands were invaded. Although it was spoken over such a vast area, no written use of it was made until relatively late, about 350 B.C. when the Samnites came into contact with the more developed culture of the Greeks and Etruscans, and began to regulate their exchanges with the Romans in writing. Ancient sources (literary, epigraphic and numismatic) have handed down both the Oscan form of the name by which the Samnites called themselves and the Greek and Latin form of the name by which other peoples called them. It seems that the Samnites called their own region Safinim and designated themselves by the name Safineis.[29] In Latin the region became Samnium and the inhabitants were called Samnites. In Greek the Samnites were called Σαυνίται and their land was called Σαυνίτις as attested by Polybius (III, 91, 9) and Strabo (V, 4, 3 and 13).[30] Probably descended from the same ancient lineage, they show in the cultural sphere many similarities (language, religion, customs), but also differences resulting from the geographical location and morphology of their respective territories. While the Frentanian Samnium faces the Adriatic coast, in contact with populations with a maritime orientation, the Pentrian Samnium is oriented toward the Mainarde and the Matese and is connected with the Campanian side. The former benefits from material conditions that allow it a higher economic development and rapid urbanization, while the latter remains anchored to more archaic forms of production and only after the Social War reached a widespread level of urbanization. While the Pentri, spread over mountainous territory, remain tied to a scattered form of settlement, with a dense network of fortifications on the heights, the Frentani, spread over a flat territory, already in the fourth century B.C. aggregate into urban centers, mostly located on the ancient routes. They would all be equally subdued and eventually their territory would be greatly reduced in size and surrounded on all sides by cities and peoples allied with Rome.[31] The Samnites can be said to make their entry into history only from 354 B.C. when, having come into contact with the Romans for the first time, they entered into a pact of non-belligerence with them (Livy, 7.19.4; Diodorus 16.45.8). This was an agreement probably motivated by the need to define the limits of their respective zones of expansion. Soon thereafter would begin a fierce and very long confrontation, protracted, albeit with interruptions, for more than fifty years (from 343 B.C. to 290 B.C.), which would end with the final subjugation of the gentes fortissimae Italiae, as Pliny the Elder defined the Samnites (Naturalis Historia III.11.106)[32] and the beginning of a process of Romanization of central and southern Italy. Pliny's words corroborated the image of a fierce and warlike people whose valiance as warriors was recognized even by the Romans, their bitter enemies, in the struggle for supremacy over the Italic peninsula. This aggressive and rough character of the Samnites, already present in ancient tradition,[33] their primitive and wild lifestyle, according to how Livy describes them (IX.13 .7. montani atque agresti), their recognition of warrior valor and military qualities, would eventually influence even the representation that ancient historical tradition handed down of the Frentani.[34] In fact, although they were the only one settled on the Adriatic coast, the tribe of the Frentani, in Strabo's scholarly interpretation (V, 4, 29), is also linked to the inland mountainous areas, according to a reconstruction made a posteriori on the basis of meager factual data.[35] After the humiliating defeat at the Battle of the Caudine Forks suffered in 321 B.C., the Romans attempted a series of alliances with various Samnite peoples (Livy,X,3,1), following a precise strategy, that of disarticulating the solid national consciousness of that people, securing the loyalty of certain tribes.[5] In 304 B.C. the Frentani, who had already been defeated in 319 B.C. by the Romans, asked for and obtained, along with other tribes, peace with Rome, making with it a foedus, a pact of alliance (Livy,IX,45,18) and obtaining in return greater spaces of autonomy. They thus became, along with the Marsi, Peligni and Marrucini, associates of Rome, which was particularly interested in keeping trade links with Apulia open. The treaty greatly benefited the Romans; in fact, the Samnites had to resign themselves to the loss of Saticula, Luceria, and Teanum Sidicinum, as well as the entire Liri valley, where the Romans had already founded three Latin colonies (Sora, Fregellae, and Interamnia) at the end of the fourth century B.C., finding themselves surrounded by civitates foederatae and peoples allied with Rome, which made it difficult for them to be able to seriously threaten Latium. And indeed after only six years there was war again, this time involving the Etruscans and Gauls.[5] It is likely that it was due to the effect of the treaty that the Frentanian community of Larinum obtained the autonomous status of civitas foederata. According to historians it was precisely the attainment of this special status as early as the beginning of the 3rd century B.C. that would have fostered the economic development and early urbanization and Latinization of Larinum, with the final transition from the primitive form of scattered rural settlements to a properly urban form.[5] The abandonment of necropolis and scattered habitation sites coincides with a gradual detachment of the ager Larinas from the rest of Frentania, the area located west of the Biferno, which instead retained the Oscan alphabet and institutions peculiar to the Pentrian area until the first century B.C. as a sign of tenacious adherence to its character as Σαυνιτικόν έθνος (Strabo, V,4,2), remaining one of the least Latinized Italic areas.[36] It was precisely this phase of change in territorial arrangements and administrative organization that initiated a process of transformation of the Frentanian economy in the direction of greater dynamism in the local economic system and thus an increasing use of currency. Although with a certain chronological approximation, it can be assumed that in the period 270-250 B.C. there were already circulating monetary issues both by the city of Larinum and by the Frentani.[37] For the preceding decades, although numerous finds are attested, it cannot be assumed, however, that these areas were in intense monetary circulation. On the basis of excavation find data, there seems to have been a fair amount of penetration of "foreign" coinage both in the Larinum region and in inland Samnium from Campanian and Apulian environments. It was not until the years of the Second Punic War that the mint of Larino began to produce abundant and articulate series of coins, following the decimal fractionation system of the Roman as, typical of cities located on the Adriatic belt.[38] A rare issue of silver obols from the 4th century B.C. with the Greek legend ΣΑΥΝΙΤΑΝ would suggest a phase of political unity of the people of Samnium. For the first time, the tip of a javelin (the saunion) appears on the reverse, within a laurel wreath, and a veiled female head, on the obverse. The presence of the ethnic in Greek characters, and not in the Oscan alphabet, suggested a provenance from the mint of Taranto, the result of a probable alliance. The archaeological data seem to confirm that the Frentanian territory was rather reluctant to the use of minted coinage, both with respect to inland Samnium and to the northern Adriatic, beginning to produce coins only after the middle of the third century BC.[39] The Frentani, for their own bronze coinage chose, as a legend, the ethnic Frentrei in the Oscan language and spelling, right-handed, to emphasize their own sphere of autonomy, and used types of Greek setting, such as the head of the god Mercury, on the obverse, and a winged Pegasus, on the reverse. Based on the finds, it is assumed that circulation was limited to the region of origin and that these coins were used as a medium of exchange in very restricted trade circles.[39] Larinum, on the other hand, by then already included in a circuit of cultural contacts and trade relations with the Campanian and Apulian worlds, used a variety of types and legends, beginning with a bronze series, with a Greek legend and Campanian type, ΛΑΡΙΝΩΝ, with the head of Apollo and Bull with a human face, dating from 270-250 BCE. C. and moving on to two types with Apulian and Campanian iconographic motifs, with Oscan legend but Latin (left-handed) spelling, Larinei (coin issued in Larino), with a head of helmeted Athena and a galloping horse, and then Larinod (coin issued from Larino), with a head of helmeted Athena and a lightning bolt.[40] The few known specimens pertaining to these issues and the lack of precise contexts mean that the dating of this issue cannot be known with certainty. These early monetary experiments in Larino are considered to be of no long duration; they remained in use for several decades, complementing the Roman coinage, which was by then spreading throughout the region; its area of circulation, however, remained confined to Samnium and the central-southern Adriatic coastal strip, as a means of small exchange. Regarding the Frentani, for a long time it was considered uncertain whether they belonged to the Samnite ethnic group, which was cast into doubt on the basis of the archaeological documentation relating to the Archaic phase: the more cultural features and ritual customs that distinguished this population from the Samnites settled in the inland Apennine areas emerged as a result of research, the more discussion of the broad questions of Italic ethnohistory was revived.[41] It is no coincidence that the ancient sources themselves (Strabo, Ptolemy, Mela, Pliny) mostly disagree on the territorial extent of Frentania and its geographical delimitation, and the geographical location of the various inhabited settlements also appears in them to be approximate and imprecise: even in the eyes of the ancient authors the history of Samnium appeared extremely changeable, like a magma in continuous modification, which in certain areas presented itself with connotations and differences that were sometimes accentuated.[42] In the mid-eighteenth century, historian Giovanni Andrea Tria also noted, "As for the origin of the Frentani, not even historians agree: some estimate that the Frentani came from the Samnites, others that they came from the Liburnians, others from the Sabines, and others from the Etruscans."[43] Precisely on the basis of this complex affinity-diversity perspective, the geographer Strabo (V,4,2) considers the Frentani an ethnically Samnite population (Σαυνιτικόν έθνος), but at the same time their region distinct from Samnium in cultural terms. After all, the Frentani in almost all ancient sources are described in a condition of peripherality to the Samnite region, in a marginal position in relation to the central Apennine area. There are not many references by ancient historians to the life of the Samnites, but archaeological excavations are yielding a rich documentation of their daily habits and activities, giving an effective insight into their daily life. Thus emerges a portrait of a population markedly different from the one described by ancient historians, who were concerned rather with conveying to posterity a narrative according to a version decidedly favorable to Rome, magnifying the exploits of their nation, depicted as a heroic saga.[44] Described by ancient sources as crude and primitive peoples, perched in the mountains, recent research has instead brought to light evidence of an extremely mobile people, capable of relating to and interacting with various Mediterranean peoples. Archaeological data attest to the existence of stable settlements, with a socio-economic organization of a simple type, based on a reduced specialization of labor, in which productive activities were mainly seasonal in nature. This was a territorial organization characterized by accentuated fractionalization, vicatim, as stated by Livy (IX,13,7; X,17,2); in flat and hilly areas, usually near watercourses and communication routes, there were scattered villages, small in size, defended by ditches or palisades (the vicus, connected to pastures, woods and cultivated land) or, in mountainous areas, fortified citadels of varying size (the oppidum defended by short walls), positioned in strategic conditions for the control of the territory.[45] In a predominantly mountainous territory, agricultural production and livestock breeding were the basis of the Samnite economy, aimed at satisfying the primary needs of the communities; in pre-Roman Samnium, livestock breeding took place in both sedentary and transhumant forms, albeit on a smaller scale than later in Romanized Samnium. Among the craft activities, wool and leather working was certainly practiced, as well as the production of pottery and bricks. Bojano, for example, represented an important tile manufacturing district, complete with its own trademark. Of no little importance was warrior activity,[46] especially for the populations of the inland areas, which was carried out in forms of robbery, forced levy, and tolls resulting from military control of communication routes, practiced through ambushes, sudden assaults, raids and ambushes. Numerous excavation campaigns carried out at Monte Vairano (in the countryside of Busso and Baranello, near Campobasso, 998 m above sea level) have unearthed a Samnite fortified settlement, dating back to the 4th century B.C. distributed over an area of about 49 hectares, articulated in houses, stores, places of worship, artisans' workshops, well distributed on a complex road fabric, protected by a long wall (of about 3 km.), which in some cases exceeds two meters in height, with related access gates and watchtowers. This is a settlement of considerable size, which presupposes the presence of a community with its own social organization, which drew up, according to a constructive logic, an organic plan for the arrangement of the area, bounded by the walls. Mortars, amphorae, jugs, loom weights were found in the various buildings, effective evidence of a cross-section of the daily life of that population. The area, inhabited even before the Samnite wars, ceased to be frequented in the mid-first century B.C. when the buildings collapsed.[47] With the rest of the Italic world, for example, contacts are evident from the presence of Etruscan bronze objects, mainly related to cultic practices. Close relations also existed with the city of Taranto, but valuable ceramics also arrived in Samnium from Apulia and Campania. Economic and commercial contacts between the Samnites and much of central southern Italy are confirmed by coins from Apulian, Campanian and Bruttian mints found in Samnium territory. Skilled exporters of lumber and the products of animal husbandry, the Samnites reached as far west as Marseille and the Balearic Islands, and as far east as the Bosporus and the Aegean Islands, from which they imported fine wine, as evidenced by wine amphorae bearing the mark of Rhodes, Chios and Knidos, found in the various necropolises of Molise. In addition, Samnite weapons and belts, evidence of their mercenary activity, have been found not only in Magna Graecia, but also in some Greek cities.[48] In direct contact with the inhabited agglomerations, they knew how to create sacred areas of particular monumentality, located in suggestive places and in the wide valleys, built with great technical skill and rich in decorative apparatuses.[48] These places of worship testify to how much in ancient Samnium life, in its daily ordinariness, was constantly imbued with the sacred, in marital life, in the work of the fields, in religious recurrences, and in mournful events.[49] In the end, the history of Samnium, seen over a long period, between the Iron Age and the end of the ancient era, is the story of a progressive evolution, with highly diversified situations depending on the geographical areas: while the center of the Samnite area remains longer bound to archaic forms (in which the dominant groups try to preserve the class structure, dating back to the 7th century), at its margins the southern periphery is about to make a qualitative leap, moving rapidly toward urbanization. While in the central-Italic Samnite areas urbanization penetrates only in the 1st century B.C., in the southern periphery between Frentania and Daunia, economic development as early as the 3rd century B.C. marches decisively toward an urban civilization.[50] Moreover, even on the Tyrrhenian side of central-southern Italy the process of urbanization takes place early, compared to the inland areas, and is closely related to advanced economic and social development, brought about by contact with the innovative trends of the Greek world. In the realities that have not yet experienced urbanization, on the other hand, production levels remain low and the development of specializations scarce.[51] Roman Period   Already at the beginning of the Hellenistic period, Larinum seemed by then to have attained a definitive physiognomy and to have acquired a preeminent role in relation to the other centers in the area. To the fertility of the soil, the strategic geographical position, the flourishing commercial activity and the numerous contacts already established with a variety of cultural circles, Larinum added, on a par with other state entities, the recognition by Rome of the status of res publica Larinatium (Livy XXVII,43,10), granted on the basis of the criteria of geographical and "political" expediency habitually used by the Romans in their activity of urbanization and administrative control of the territory.[5] This favored the development of an autonomous administrative role and the establishment of an autonomous local bronze coinage, as well as the presence of accentuated features of mixed Osco-Latin culture, not documented in the region north of the Biferno River. As a result of the Roman order, the city, now rich and populous and endowed with its own laws and magistrates, also succeeded in producing a rapid transformation of the organization of its urban center and initiating a concentration of investment initiatives of a building and infrastructural nature, in an effort to strengthen the urban entity. Investments that involved not only public spending, but also that of private origin.[52] Excavation investigations conducted over the years in the settlement of Piana San Leonardo, although limited to areas that are not very large, have revealed a rather complex and chronologically articulated settlement reality, starting from the Archaic period and reaching the late Hellenistic period, with traces of cobblestones, paved streets, public paving, craft and dwelling quarters, and a sacred area (Via Jovine), which point to increasingly advanced building techniques.[53] It is known that, with the final Augustan order, the Biferno River became the natural boundary between Regio IV and Regio II, between which the Frentani were divided. The territory west of the river, assigned to Regio IV, retained the name Regio Frentana and included the cities of Anxanum (Lanciano), Histonium (Vasto), Hortona (Ortona), and Buca (possibly Termoli) (Pliny, Naturalis Historia, III, 106). The territory east of the Biferno River, assigned to Regio II, was in fact assimilated into Daunia: it included Cliternia, Teanum Apulum and Larinum, going as far as Fortore, the flumen portuosum Fertor mentioned by Pliny (N. Hist. III, 103). However, this particular physiognomy of Larino allowed it to preserve, in its official name, memory of its ethnic pertinence to the Frentani area: Larinates cognomine Frentani, Pliny in fact writes (N. Hist. III, 105). The divergences existing among ancient texts, therefore, regarding the exact attribution of Larinum to a precise territorial area should not be surprising. The city is mentioned by the geographer Stephanus of Byzantium as πόλις Δαυνίων, in Pomponius Mela it is only an oppidum of Daunia, for Ptolemy it is one of the main centers of the Frentani, according to Pliny the Elder it is a Frentanian city, but it is included in Regio II, which includes Apulia.[54] Systematic excavations, carried out since 1977 at Piana San Leonardo, have yielded a very interesting stratigraphic sequence, albeit only in limited areas, and have made it possible to identify, albeit discontinuously, the area of extension of the Roman city, although at present it is not possible to specify exactly the perimeter of the walls. In fact, the building expansion of Larino, which occurred in the post-war period precisely in the area of Piana San Leonardo to meet the housing needs of the community, overlapped almost faithfully with the ancient site, realizing a rapid and almost complete urbanization of the entire area. This condition resulted, in the following years, in an extremely problematic situation from the point of view of archaeological research, whereby it was possible to explore only those few remaining vacant areas, located between the modern built-up areas, the only ones susceptible to conservation and enhancement initiatives of those archaeological evidences not yet compromised by the building development.[55] Archaeological explorations at Piana San Leonardo have ascertained the presence of settlements dating from the late 5th century B.C. - first half of the 4th century B.C. consisting of cobblestones and remains of perimeter walls of buildings. Later, other buildings were set on top of the older ones, dating from the late 4th century - early 3rd century B.C. that adopted more advanced building techniques, with dry-stone walls, with irregular stones and with rows of tiles, or bonded with cement mortar. Later on, the area corresponding to the present Jovine Street came to assume a sacred destination: in fact, the Hellenistic phase (late 3rd century B.C. - early 2nd century B.C.) is characterized by the presence of a large amount of votive material, which can be attributed to the activity of a sanctuary, most likely to be identified with a building of considerable size, of which some large, well-squared blocks of tuff stone remain. Judging from the votive material, the area was dedicated to a female deity, most probably Aphrodite: in fact numerous are the terracotta figurines depicting the goddess. The temple of the goddess has been partially recognized in a structure of limestone blocks, which is complemented around the 2nd century B.C. by a rectangular hall paved with mosaic, forming a lattice pattern. At this stage, albeit limited to certain sectors of the city, well-squared tuff blocks, which would be used for a long time, were adopted only for larger buildings. The area adjacent to the temple was used, throughout the period of the sanctuary's operation, as an unloading area for votive material, which is scattered throughout the area. In addition, limited to certain zones, the area was also used for special sacrifices, as evidenced by the presence of piles of pebbles arranged in a pyramid shape, mixed with coals, clay figurines and votive figurines.[56] The votive objects include ceramic material, clay and bronze figurines, and many coins, including a hoard of twenty-two, hidden in an earthenware jar, forming a veritable treasure trove, dating to the mid-2nd century B.C. But the most distinctive element of the votive deposit can undoubtedly be considered the small-scale coroplastic art: these are figurines made in molds, which are therefore hollow internally and mostly of homogeneous clay. The front part is more accurate in detail, the back part is only barely sketched and of coarse workmanship; the heads, executed in all round, making use of two matrices, were usually created separately and then applied to the base of the neck. Of the different types attested at Larino, the draped female figures predominate, following the Attic style that spread rapidly throughout the Hellenistic world until the first century BCE.[5] The presence of these statuettes constitutes an interesting document for understanding the different directions of diffusion of Hellenistic cultural iconographic motifs from Taranto and the Magna Greek area in general and directed not only toward Campania and Latium, but also toward the Middle Adriatic regions. This confirms the relevant role played by the city in the spread of these and other products to vast areas of central Italy.[5] Another of the most widely explored areas is the one in the Torre Sant'Anna locality, which knew a long life, passing through various phases. Initially there was a refined domus, built around the 3rd-2nd century BC, of which the atrium, paved in polychrome pebbles, and some surrounding rooms survive. The richness of the building is evidenced by the presence of a large impluvium with a polychrome mosaic pavement, depicting an octopus in the center and four groupers in the corners.[5] But the life of the domus was abruptly interrupted due to supervening public needs. The area, in fact, was designated to house a public area, with monumental buildings, including the forum, a large structure, quadrangular in plan, made of opus mixtum of latticework and brickwork. The building consisted of a series of exedras, with a central apse, opening onto a porticoed interior. Behind, with access to the east, the brick wall sections of another building with a pronaos are preserved, perhaps originally covered on the inside with marble and mosaic flooring, of which a sacred destination is hypothesized, perhaps the temple of Mars to which Cicero alludes when he reports on the presence in Larino of the Martiales, public slaves, consecrated to the worship of the god according to ancient religious traditions.[5] A third area of Piana San Leonardo removed from the building sprawl is the one between the kindergarten and the Civil Court, where an urban sector with a paved road and sidewalks has come to light, inexplicably, along which residential buildings on one side and artisanal buildings on the other are evident. Inexplicably, because it is a rather decentralized area from what was believed to be the limit of the ancient city. Some living quarters still preserve mosaic and opus signinum floors; the artisanal part, although in worse condition, preserves tanks, opus signinum floors, and runoff channels.[57] In 91 BC, the Social War broke out: it was the last challenge against Rome by the Italic peoples. The Samnites also rose up to obtain full Roman citizenship, and formed, along with the other peoples, the Italic League; they represented, in the line-up of insurgents, the strongest and most determined element. In the face of the rebels' initial successes, Rome reacted by enacting a number of laws (the lex Julia and the lex Plautia Papiria) granting Roman citizenship to all Italic peoples who were not at that time in arms or who were willing to lay them down. The initiative turned the tide in Rome's favor since a large proportion of the rebels accepted the proposal. The long wars had now sapped Italic resistance and Rome's upper hand had become inevitable. The granting of citizenship enabled the Romans to organize land use through the founding of municipia, not only seats of administrative power but also organizational centers of productive, agricultural, building and commercial activities. Municipalization did not immediately come easy, because it came to clash with the Italic system, traditionally linked to an agricultural-pastoral economy expressed in a form of scattered settlement. In time Samnium also adapted to the Roman municipal system, a prelude to a complete Romanization of the territory: in the Molise area, municipalities were established in Isernia, Venafro, Trivento, Bojano, Sepino and Larino, according to the organizational needs of central power. During the same period, evidence of life in almost all Samnite sanctuaries disappeared.[58] The Samnites, rebels in the social war, had not, however, forgotten the opposition shown by Lucius Cornelius Sulla to their admission to Roman citizenship: when civil war broke out, therefore, they did not hesitate to side with Gaius Marius. When Sulla returned from the East in the year 83 BC, he decided that he would fight the last of the Samnite wars. The bloody battle of the Colline Gate (82 B.C.) was for the Samnites their last great battle: guilty of having supported Marius' populares, they had to reckon with the merciless vengeance of the victor, who was particularly against them, convinced, as Strabo (V ,4, 11) narrates, that no Roman would be safe as long as an organized Samnite community existed.[5] The defeat marked the end of the Samnites as a state entity, endowed with their own identity, institutions, language, and religion. Never again would they play a role in the Roman state, confined to obscurity and largely ignored. From that moment on, the Romans felt no need to reconcile with them and began a slow process of denationalization of Samnium. Large tracts of territory were confiscated and distributed to veterans; those not assigned became ager publicus available to farmers. Even the Oscan language was downgraded to a peasant dialect, giving way completely to Latin. Already by the end of the first century CE a large percentage of the population of Samnium was no longer to be Samnite.[5] At a later date, very few Samnites occupied the high commands of the army, and even in the political sphere very few held high-ranking official positions or managed to sit in the Roman Senate.[59] Although the earliest phases of Larino's history are entrusted to the results of archaeological research, only one, but very authoritative ancient source, Cicero, is now available to us for a record of what life in a provincial town like Larino might have been in the first century B.C. in the years immediately following the Social War, a portrait of local society projected into the context of the much broader events of Italy at the time. In 66 BC. Cicero, in his 40s, delivered in Rome before the criminal court an oration in defense of the native of Larinum Aulus Cluentius Habitus (the famous Pro Cluentio), an aristocrat of equestrian rank, a man of "ancient nobility", accused by his mother Sassia of attempted murder of his stepfather Statius Oppianicus and of attempting to bribe the trial judges.[5] To attest their esteem to their friend and testify on his behalf, not only the noblest citizens of the Frentani, Marrucini and Samnites of the interior came to Rome, but also Roman equites from Lucera and Teano Apulo. This was undoubtedly a very "talked about" trial, since the Cluentii belonged to the equestrian rank and were one of the wealthiest and most prominent families in the city. By the time the events described by Cicero took place, Larino had become an industrious, wealthy and lively city: it had gone through various urban arrangements, festivals and public games were organized there, markets were held, and intense trade was interwoven, thanks to the rapid and easy road connections. During the recent social war the popular party fought on the side of the Italics, the conservative party, of ancient nobility, sided with Sulla. The city was torn apart by internal strife and violent unrest, clashes between the two opposing factions, who unscrupulously resorted to any means to vie for political power with their opponent. This is the climate that now characterizes the crisis of the republican regime in the last century B.C.[5] The oration offers Cicero cues to describe, even if only incidentally, the customs and standard of living of the aristocratic families of Larino, many of them in close friendship and business relations with senators and prominent figures in the capital, where they certainly went with considerable frequency. Families accustomed to living in luxury and comfort, deriving their profits from business, pastoral and agricultural activities (negotia, res pecuariae, praedia).[60] Very little is known about the affairs of Larino in the late imperial age: certainly the area was still inhabited in the fourth century CE, a time to which date the approximately six thousand bronze coins found by chance in the locality of Lagoluppoli, perhaps near an ancient road, now disappeared, that continued from Larino to Rotello, and the mosaics found in old excavations, which attest to the vitality of the town. Certainly Larino, too, was affected by the terrible earthquake of 346 A.D. that devastated the entire Samnium, as evidenced by inscriptions on public buildings restored by the state. It is precisely from Larino that comes an inscription relating to Autonius Iustinianus, the first governor of the newly established Samnii Province, who was particularly concerned with the disastrous situation in Isernia. Samnium, in fact, after being united with Campania, towards the end of the 3rd century AD, with the profound administrative reorganization of the Empire promoted by Diocletian, again became an autonomous province towards the middle of the 4th century AD, preserving its territorial unity unaltered until the end of the 6th century AD when, with the advent of the Lombards, it definitively lost its administrative autonomy.[5] In the early medieval age the whole site of Piana San Leonardo was probably already in a state of abandonment, the object of systematic plundering of stone materials, used for the construction of the dwellings of the medieval center, further downstream; in particular, the brick parts of the amphitheater were removed, which, by then no longer in use, was occasionally used for burials and was also used for makeshift shelters in some spaces of the upper ring of the cavea; in the ramp of the east gate functioned until the beginning of the 8th century AD. C. a lime kiln.[61] UrbanismDespite countless archaeological excavations and tests carried out in recent decades in different parts of its urban fabric, it is still difficult to say precisely where and how far the city extended: it is presumable, especially on the basis of the archaeological evidence, that it occupied an area, so to speak, in the shape of a bird's wing, with the amphitheater at the apex (located, therefore, a little on the edge of the town) and the two arms arranged one toward the Montarone hill (the area currently most affected by modern construction) and the other toward Torre Sant'Anna (presumably the area of the Roman town richest in public and private buildings).[5] This urban conformation was certainly conditioned by the particular sloping terrain and the pre-existence of connecting road routes, which determined the choice of housing sites. Certainly an ancient road connected Torre Sant'Anna with the Biferno valley floor, just as the present road to Montarone serves, as it did then, as a link with the Larino Plain and the Adriatic coast. A third arm of the road, which has survived to the present day, is the one that runs inland from the amphitheater in the direction of Casacalenda, where the Roman necropolis stood, as evidenced by the numerous epigraphs and tombstones found in the late 19th century, when the present railway station was built.[62] Although within the Frentanian area Larino is the best known city, due to the ruins that have remained partially always above ground and thanks to the results of recent archaeological research, gradually more and more extensive, only since the 1960s was a first archaeological constraint extended to the areas immediately adjacent to the amphitheater, already abundantly urbanized. Since the 1970s the municipal administration, in conjunction with the establishment of the Archaeological Superintendence of Molise, has constructively addressed the problem concerning the protection of those areas still free of construction, conditioning the destination of the plots, which were thus spared from building development. Since the implementation of expropriation measures was no longer feasible, it was possible to proceed with archaeological exploration only in those areas that remained vacant, carrying out, where necessary, restoration and conservation work in the areas where archaeological evidence (mosaics, pavements, artifacts) was found.[5] All the structures found in the last thirty years, although immersed among modern building agglomerations, have undergone consolidation and restoration: mosaics, in particular, have been placed on specific supports, positioned in situ so that they can be removed, if necessary, at any time.[63] However, due protection has been ensured to each artifact, in order to slow down its disintegration process, while still leaving it fully usable. In fact, between the possibility of removing a mosaic to display it in the hall of a museum and that of leaving it in its original site, after careful restoration operation, this second solution was mostly preferred, because of the need to give back to the artifact its most complete usability, preserving it in its original environment. The Roman amphitheater With its ruins, which have always remained partially outcropping, the amphitheater is certainly the most famous ancient monument in Larino; it has always represented the symbol of the city. In recent decades, however, the area has been affected by intensive urbanization, as it is adjacent to the railroad and the state road.[5] The bathsIn the immediate vicinity of the amphitheater, but still within the current archaeological park, it is possible to admire the remains of the sumptuous baths, rich in polychrome mosaics, with representations of fantastic as well as marine animals, and geometric figures; it is currently possible to visit two baths intended for bathing in hot, warm and cold water (calidarium, tepidarium, frigidarium), the compartment in which water heating was produced by fire (praefurnium), a room with suspensurae (i.e., with the small columns that supported the raised floor in which the hot air passed), a large pillar pertaining to the porticoes, an accurate water drainage system, consisting of a mighty sewer, covered by tiles arranged as a cist. The special feature of this archaeological find is that it still preserves the hypocaust layout, that is, the underground rooms in which the ovens and other service rooms were located. Due protection has been provided for what has been brought to light by installing an appropriate covering structure; in addition, a metal walkway allows the mosaic to be viewed from above without treading on it.[5] The forumIn the Torre Sant'Anna excavation area, the eastern side of the Forum, with its monumental buildings, has been identified: in this urban sector several phases are concentrated, clearly visible. The first, dating from the 3rd - 2nd century B.C., does not yet provide for public use; a large and refined domus is located there, of which the atrium paved in halved polychrome pebbles and some of the rooms that were distributed around the atrium and on either side of the wide access corridor can be found. In addition to the pavement of the atrium, the special feature is also the presence of a large impluvium whose polychrome mosaic floor depicts an octopus in the center and four groupers at the corners, with a wide marginal band with vines and bunches of grapes.[5] This part of the ancient city underwent two successive building phases: after its construction between the second half of the second century B.C. and the first half of the first century B.C., it was heavily renovated in the fourth century A.D., when the governor of the newly established Samnii Province had to start restorations after the disastrous earthquake that struck the area in the year 346 A.D. The life of the city continued thereafter, but in a stunted way: slowly the buildings, by then abandoned, began to undergo systematic spoliation, for a reuse of materials. Modest hovels were erected here and there, built from stripped materials.[5] The domusThe domus located near the Forum, in terms of its size, decorative richness, and the economic effort put into its construction, certainly belonged to one of the families of the Larinian agrarian aristocracy, whose rise, which began in the 3rd century B.C. would continue without interruption. In fact, at the beginning of the 1st century BC the domus underwent renovations in the area of the impluvium and modifications of its previous state. Then, after about a century, its existence was abruptly interrupted due to supervening public needs: the area was destined to house monumental buildings, which bordered the eastern side of the Forum, positioned on a large structure with a quadrangular plan, made of opus reticulatum and bricks. The side facing the Forum opened onto the porticoes by means of three rooms; the opposite side was divided into a series of exedras with a central apse, which in turn opened onto an inner porticoed space.[5] Behind it, with access to the east, is another building with a pronaos, originally covered inside with fine marble and with a mosaic floor; the brick wall sections of it are preserved today, up to a considerable height. It is hypothesized that this building, situated in a prominent position on one side of the Forum, had a sacred purpose, and was the probable temple of Mars, alluded to by Cicero, when he speaks of the presence in Larino of the Martiales assigned to the worship of the god.[5] The three polychrome mosaics, now preserved in the Ducal Palace, testify to the richness of the decorations that graced the domus of local notables; the most striking one is the mosaic depicting the central scene of the Lupercal (with the classical pose of the she-wolf suckling the twins), surrounded by a complex frame with acanthus bushes at the corners and spirals with hunters and animals. The other two mosaics, the Lion and Bird mosaics, also inspired by classical models, belonged to an early third-century AD domus not far from the amphitheater.[5] The mosaicsThe numerous mosaics, found by chance in the town of Larino, cover a time span of at least five centuries, from the 2nd century B.C. to the 3rd century A.D., and testify to the richness of the decorations that adorned the domus of local notables; of the eight tessellated mosaics that still exist today, half are polychrome. Of the latter, the three most conspicuous and longest known are currently preserved in the local Civic Museum, at the Ducal Palace in Larino. They also testify that in the Larino of the imperial age there were workers with excellent technical qualities, not only organized in workshops, but probably also itinerant.[64] The first two mosaics, known by the names of the Lion and the Birds, came to light in 1937 in a third-century AD domus on Julius Caesar Avenue (near the present Reclamation Consortium), located not far from the amphitheater, of which part of the walls with a limestone-block lattice facing remains. Both are of considerable size and are inspired by classical models. Excavation records from 1941 show that they were adjacent, separated only by a wall. In the summer of 1949 they were detached, restored, and musealized in their present location.[5] The first (m. 6.02 x m. 5.30), overall in a good state of preservation, depicts in the central emblem a roaring lion advancing from the left, his gaze turned backward, inserted in a white background carpet in which some palms are recognizable; the outer frame has plant motifs (with stylized ivy shoots), while the marginal band has the four-headed braid motif on a black background and at the margins a wide band on a white background with ivy racemes is drawn.[5] The second (m. 5.07 x m. 5.30), which is more incomplete, depicts in the central field numerous vine shoots with vine leaves, on which birds of various kinds perch, facing the center; it has a wide marginal band with ivy racemes and a series of concentric frames with ogive and polychrome braid motifs on a black background.[65] A third mosaic (m. 6.08 x m. 7.17), known as the Lupercal, was found in 1941 at the present Agricultural Technical Institute, near Railway Station Square, and in 1973, after a long series of stormy events, it was restored and placed together with the other two. It is undoubtedly the most conspicuous and well-known one, dates from the third century AD and is in an excellent state of preservation. It depicts in the lower part of the central field the Lupercal scene, with the classical pose of the she-wolf in the act of suckling the twins in the cave, and in the upper part two shepherds, in profile, observing the scene in amazement, from the top of a hill. The depiction of the she-wolf, whose striped cloak rather resembles a tiger, is unusual. The central field is surrounded by a complex ornate frame, with large acanthus heads at the four corners and spirals with six hunters, armed with arrows and javelins, and wild animals in profile (felines, antelopes, deer). The mosaic scene is found reproduced on altars, tombs, vases, paintings, coins, and monuments of various kinds, as it is a widespread iconography in the ancient world.[66] In contrast, the fourth polychrome mosaic (m. 2.72 x m. 4.60), known as the Octopus, found among the remains of a Hellenistic-era domus near Torre Sant'Anna, is still located in situ. It constitutes the floor of an impluvium for collecting rainwater and depicts a large octopus in the center, with eight tentacles, and four groupers at the corners, rendered with great naturalism, in a frame of vine shoots with bunches of grapes, represented schematically. Brought to light first in 1912 and then in 1949, it was detached in 1981, properly restored, and finally relocated in 1985 to the site of discovery. It is currently on display for visitors under a protective metal structure. It is a subject commonly used for the decoration of particular environments, such as baths, fountains and public baths.[67] The bichromatic, black-and-white mosaics were all found later than the polychromatic ones. In 1971, in the course of an excavation, the mosaic known as the Dolphins (m. 6.70 x m. 4.90) was found in Via Tito Livio, near the municipal stadium. Buried, it was unearthed in the summer of 1985, was detached, restored and welded onto movable fiberglass panels. Given its size, the mosaic presumably embellished a prestigious room of considerable size. It has an outer decorative band of waves running to the left and a central band with meandering swastikas alternating with panels with figurative and decorative subjects; in two of them appear a skyphos and an aryballos and in two others dolphins. The figures, despite their small size, are well defined in detail. The mosaic has a conspicuous gap over the entire right half, but among the two-colored ones it is definitely the most elegant and beautifully executed.[68] In 1973, an apsidal mosaic (m. 5.10 x m. 7.00) was discovered near that of the octopus, in the Torre Sant'Anna locality, during test excavations, and was provisionally left in situ, covered by a thick layer of river sand. It was unearthed in 1981, detached and restored. Placed on fiberglass panels, it was relocated in situ on a concrete base. It features a square central field, decorated with geometric motifs, shamrocks and lotus flowers, enclosed in three concentric frames and an apsidal lunette. In 1984, on Morrone Street, during construction work on the municipal kindergarten, in the area adjacent to the Palace of Justice, the so-called Kantharos mosaic (m. 1.45 x m. 2.25) was found, conspicuously damaged during earthworks in the area. The Superintendence verified, through the stratigraphic sequence, the presence of pit tombs excavated in the tuff layer, dating from the Archaic period, and the presence of settlement structures dating from the later Hellenistic-Roman period. The mosaic, in a poor state of preservation, has geometric motifs with octagons and lozenges.[5] Another mosaic is the so-called opus signinum mosaic, found during excavations carried out by the Superintendence in the years 1977-1978 in the area of Piana San Leonardo, in Via F. Jovine. It dates back to the 2nd century B.C. and constitutes the pavement of a large building from the Hellenistic period, of which only squared blocks of sandstone remain, in an area of sacred use. It is composed of a red earthenware mixture, with a grid of lozenges in the central part and an outer band with geometric patterns of squares alternating with swastikas. In 1983 it was detached and restored, mounted on fiberglass panels, and stored in the Superintendency's repositories.[69] See alsoReferences

Bibliography

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||

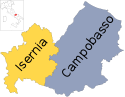

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia