|

L'étoile du nord

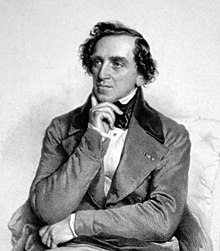

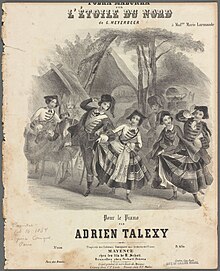

L'étoile du nord (The North Star) is an opéra comique in three acts by Giacomo Meyerbeer. The French-language libretto was by Eugène Scribe. The work had its first performance at the Opéra-Comique, Paris, on 16 February 1854.  Much of the material, including some plot similarities (with the flautist Frederick the Great substituted by the flautist Peter the Great), derived from Meyerbeer's earlier 1844 Singspiel Ein Feldlager in Schlesien.[1] However, there also are some significant differences, perhaps the most important of which is that it was permissible to actually have Peter the Great take part in the action, which was not the case for Frederick, who had to play his flute off-stage, since members of the Prussian royal family were not permitted to be impersonated on the stage in Berlin where that work had its premiere. Peter does more than just take part in the action, since he ends up being the romantic lead. A notable feature of the opera is the triple march in the finale to the second act. A rebellion against the Tsar is deflected as the "sacred march" is heard. The troops are then joined by a regiment of grenadiers from Tobolsk, to the music of a different march, followed by a regiment of Tatar cavalry to the music of a third march. Roles

SynopsisAct 1 A village square in the vicinity of Vyborg, on the shores of the Gulf of Finland. On the left, the rustic house of George Skawronski which is accessed by an external staircase. Right, the entrance to the church. In the background, rocks, and on the horizon, the Gulf of Finland. Ships' carpenters rest from their work and enjoy a meal break as Danilowitch, a pastry-chef from Russia, hawks his pies. Among the carpenters are Peter the Great of Russia, disguised as the lowly Peters Michaeloff. The absence of the lovely Catherine, who usually serves the workers, is noted, and the carpenters tease Peters for being in love with her, which annoys him. The carpenters propose a toast to Charles XII of Sweden, Russia's enemy, which angers Danilowitch and Peters, both of whom are Russian. The bell rings for the carpenters to return to work, and a potentially ugly scene is averted. Left alone, Peters tells Danilowitch that he is indeed in love with the beautiful Catherine and has even learned, like her brother Georges, to play her favourite tune on the flute in order to please her. The two Russians Danilowitch and Peters decide to return to their country together. At that moment Georges is heard playing Catherine's tune on the flute as he enters, followed by Catherine, who tells her brother that Prascovia, whom he loves, can now be his as Catherine has obtained consent to her marriage to Georges. Catherine tells Peters that her mother as she died prophesied that Catherine's life would be guided by the North Star; she would meet a great man and secure a brilliant future for herself. Catherine had been impressed by Peters at first, thinking he has a grand and impressive quality to him, but is now not so sure. She is disappointed by his drinking, she tells him, which angers him. Prascovia rushes in with news that Cossacks have arrived and are pillaging and looting the village. Catherine disarms Gritzenko, the Cossacks' leader, and the rest of his men, by disguising herself as a gypsy, telling their fortunes, and leading them in song and dance. She prophesies that Gritzenko will become a Corporal. Peters and Catherine declare their deep love for each other and exchange rings. Georges and Prascovia return, distraught that Georges has been drafted by the Cossacks. Catherine tells them not to worry and prays for their happiness (Prière: "Veille sur eux toujours"). Their wedding takes place, as Catherine, disguised as a Cossack, takes her brother's place and steps into the barge taking the new recruits away (Barcarolle : "Vaisseau que le flot balance"). Act 2 A military camp of the Russian army The vivandières Nathalie and Ékimona sing and dance for the Russian soldiers as they drink. Catherine is in the camp disguised as her brother Georges. Gritzenko, now a Corporal, has come into possession of a letter which he asks "Georges" to read out to him, as he is illiterate. The letter discusses a conspiracy against the Tsar. This rebellious feeling is increased when General Yermoloff enters with the news that the knout, a heavy whip, will thenceforth be used to discipline soldiers. A tent has been set up to serve as headquarters for the recently arrived Peters and Danilowitch, his aide. Catherine is shocked to see Peters drinking heavily and flirting with the two vivandières. She attempts to put a stop to this but Peters orders "him", as he thinks, to be taken away and shot. It is only after she has left that Peters realises that it is Catherine in disguise that he has ordered killed. She has sent him back his ring along with the letter that reveals a plot against the Tsar on the way to her execution. Gritzenko enters with the news that "Georges" escaped execution by running away and swimming across the river. Peters reveals that he is really the Tsar himself, and thereby crushes the rebellion. As massed military bands arrive (Marche sacrée), all proclaim their loyalty to him. Act 3 A rich apartment in the Tsar's palace. On the left, a door overlooking the gardens. On the right, a door leading to the palace apartments. At the back of the stage, a large window opening onto the park. Peter, in his rightful place as Tsar, is missing his life as a simple carpenter and Catherine, the girl he loves (Romance: "Ô jours heureux de joie et de misère ".) He has invited the carpenters he knew in Finland to come and visit him. Danilowitch assures Peter that Catherine is still alive and sets out to find her. Gritzenko enters with the news that the carpenters from Finland have arrived. Peter recognises him as the person who let Catherine escape and orders him to produce her on pain of execution. Georges and Prascovia arrive with the others from Finland. They fear that Georges will be executed as a deserter. Danilowitch returns - he has found Catherine, but the girl, thinking that Peter no longer loves her, has gone mad. Peter however knows how to restore her sanity - he gets out his flute and plays her favourite tune (Air with two flutes:" La, la, la, air chéri"). Her wits are restored, she learns that the man she loves is Tsar of Russia, who will marry her, and she is acclaimed by all as the new Empress of All the Russias.[2] Composition historyMeyerbeer and his librettist Eugène Scribe had presented sensationally successful French grand operas at the Paris Opéra. After the tremendous success of their Le prophète in 1849, Émile Perrin, director of the Opéra-Comique, invited Meyerbeer to compose a work in that genre for his theatre. Meyerbeer had long wanted to try his hand at this typically French style of work, and he decided to adapt his German singspiel Ein Feldlager in Schlesien, presented in Berlin in 1844, for that purpose.[3] Ein Feldlager in Schlesien, a celebration of the Hohenzollern dynasty ruling in Berlin and their illustrious ancestor Frederick the Great, had already been adapted into a piece for Vienna under the title Vielka in 1847 - Vienna being the capital of the ruling Habsburg dynasty, a glorification of the Hohenzollerns would not have been appropriate.[4] Meyerbeer's inherited wealth and his duties as official court composer to King Frederick William IV of Prussia meant that there was no hurry to complete the opera, and he and Scribe worked on the piece for more than four years before its premiere.[4] Peter the Great did travel through Western Europe under the assumed name "Peter Michaeloff" and worked incognito for a time on a wharf as a shipbuilder.[5] His second wife Catherine's origins are obscure; she worked as a servant for a time and seems to have had a connection with the Russian army,[6] which provided the basis for the switch of the libretto from Frederick the Great of Prussia to Peter the Great of Russia. These adventures of Peter the Great while working in disguise as a shipbuilder in Western Europe had already served as the basis for numerous comic operas including Il borgomastro di Saardam by Donizetti, 1827, and Zar und Zimmermann by Albert Lortzing, 1837.[7] Performance history L'étoile du nord was first performed at the Salle Favart by the company of the Opéra-Comique, Paris, on 16 February 1854. It was a big success, and in the following year was given in Dresden under the composer's baton, with Jenny Ney.[8] It was soon given in all the major theatres of Europe, North Africa, and the Americas. The Max Maretzek Italian Opera Company staged the work's United States premiere on September 24, 1856, at the Academy of Music in New York City.[9] The opera stayed in the repertory throughout most of the 19th century, but virtually disappeared by the early 20th century. However, the two big coloratura showpieces – the prayer and barcarolle in act 1 and the air with two flutes in act 3 – were still occasionally recorded by famous prima donnas such as Amelita Galli-Curci and Luisa Tetrazzini. The work has been revived in recent years: by Opera Rara in 1975, at Wexford (with Elizabeth Futral as Cathérine) in 1996 and by Kokkola Opera in Kokkola and Helsinki, Finland, in 2017.[10] MusicMost of the music in the piece is new, not adapted from Ein Feldlager in Schlesien. Meyerbeer composed some of the pieces in a light, humorous style largely new to his work in a Rossiniian spirit of playfulness, but there are also elements of the grand opera mode he had made so successful, for instance in the finale to the second act, with huge massed choruses, stage bands and processions.[4] Critics of the original production much admired many features of the work's orchestration, including the use of harps in the barcarolle in act 1 and the two flutes in the third act mad scene.[4] RecordingsBoth of the recent revivals are available, the first (Opera Rara) on a privately issued CD ROM, and the second (Wexford) on a commercial CD. The first is rather significantly cut, while the second has very minimal musical omissions but greatly abridged dialogue.

BalletIn 1937 Constant Lambert arranged excerpts from this opera and from Le prophète into the ballet Les Patineurs, choreographed by Sir Frederick Ashton. ReferencesNotes

Sources

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia