|

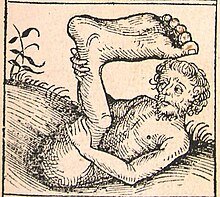

Kui (Chinese mythology)Kui (Chinese: 夔; pinyin: kuí; Wade–Giles: k'uei) is a polysemous figure in ancient Chinese mythology. Classic texts use this name for the legendary musician Kui who invented music and dancing; for the one-legged mountain demon or rain-god Kui variously said to resemble a Chinese dragon, a drum, or a monkey with a human face; and for the Kuiniu wild yak or buffalo.  Word While Kui 夔 originally named a mythic being, Modern Standard Chinese uses it in several other expressions. The reduplication kuikui 夔夔 means "awe-struck; fearful; grave" (see the Shujing below). The compounds kuilong 夔龍 (with "dragon") and kuiwen 夔紋 (with "pattern; design") name common motifs on Zhou dynasty Chinese bronzes. The chengyu idiom yikuiyizu 一夔已足 (lit. one Kui already enough") means "one able person is enough for the job". Kui is also a proper name. It is an uncommon one of the Hundred Family Surnames. Kuiguo 夔國 was a Warring States period state, located in present-day Zigui County (Hubei), that Chu annexed in 634 BCE. Kuizhou 夔州, located in present-day Fengjie County of Chongqing (Sichuan), was established in 619 CE as a Tang dynasty prefecture. Kuiniu 夔牛 or 犪牛 is an old name for the "wild ox; wild yak". The (1578 CE) Bencao Gangmu[1] entry for maoniu 氂牛 "wild yak", which notes medicinal uses such as yak gallstones for "convulsions and delirium", lists kiuniu as a synonym for weiniu 犩牛, "Larger than a cow. From the hills of Szechuan, weighing several thousand catties." The biological classification Bos grunniens (lit. "grunting ox") corresponds with the roaring Kui "god of rain and thunder" (see the Shanhaijing below). Translating kui 夔 as "walrus" exemplifies a ghost word. The Unihan Database lists the definition as "one-legged monster; walrus".[a] However, Chinese kui does not mean "walrus" (haixiang 海象 lit. "sea elephant"), and this ghost first appeared in early Chinese-English dictionaries by Robert Henry Mathews and Herbert Giles. Mathews' Chinese-English Dictionary[2] translates kui as "A one-legged monster; a walrus; Grave, respectful", which was adapted from A Chinese-English Dictionary[3] "A one-legged creature; a walrus. Grave; reverential". Giles's dictionary copied this "walrus" mistake from his translation[4] of the Zhuangzi (see below), "The walrus said to the centipede, 'I hop about on one leg, but not very successfully. How do you manage all these legs you have?'" He footnotes, "'Walrus' is of course an analogue. But for the one leg, the description given by a commentator of the creature mentioned in the text applies with significant exactitude."     CharactersThe modern 21-stroke Chinese character 夔 for kui combines five elements: shou 首 "head", zhi 止 "stop", si 巳 "6th (of 12 Earthly Branches)", ba 八 "8", and zhi 夂 "walk slowly". These enigmatic elements were graphically simplified from the ancient Oracle bone script and Seal script pictographs for kui 夔 showing "a face of demon, two arms, a belly, a tail, and two feet".[5] Excepting the top 丷 element (interpreted as "horns" on the ye 頁 "head"), kui 夔 is graphically identical with nao 夒 – an old variant for nao 猱 "macaque; rhesus monkey". The Oracle and Seal script graphs for nao pictured a monkey, and some Oracle graphs are interpreted as either kui 夔 or nao 夒. The (121 CE) Shuowen Jiezi, which was the first Chinese dictionary of characters, defines nao 夒 and kui 夔.[6]

Kui, concludes Groot, "were thought to be a class of one-legged beasts or dragons with human countenances." Most Chinese characters are composed of "radicals" or "significs" that suggest semantic fields and "phonetic" elements that roughly suggest pronunciation. Both these 夔 and 夒 characters are classified under their bottom 夂 "walk slowly radical", and Carr notes the semantic similarity with Kui being "one-legged".[8] Only a few uncommon characters have kui 夔 phonetics. For instance, kui 犪 (with the "ox radical" 牛) in kuiniu 犪牛 "wild ox; wild yak", and kui 躨 (with the "foot radical"足) in kuiluo 躨跜 "writhe like a dragon". EtymologiesThe etymology of kui 夔 relates with wei 犩 "yak; buffalo". Eberhard[9] suggested Kui "mountain spirits that looked like a drum and had only one leg" was "without doubt phonetically related" to the variant name hui 暉; both were classified as shanxiao 山魈 "mountain demons" ("mandrill" in modern Chinese). He concludes there were two series of names for "one-legged mountain imps", xiao or chao in the southeastern languages of Yue and Yao, and kui or hui "from a more western language". Schuessler[10] connects the etymologies of the word wei 犩 "wild buffalo" < Late Han ŋuɨ and the ancient word kui 夔 or 犪 "a large mythical animal of various descriptions … with one foot … as strong as an ox … a large buffalo" < Late Han guɨ < Old Chinese *grui or *gwrə. The Chinese mythical kui 夔 originated as a loanword from a Kam–Tai source (cf. Proto-Tai *γwai 'buffalo' and Sui kwi < gwi 'buffalo'), comparable with Proto-Austronesian *kəbaw (cf. Tagalog kalabao, Malay kĕrbao, and Fiji karavau). Chinese wei 犩 "wild buffalo" derives from "ultimately the same etymon as kui", but the source might have been a Tibeto-Burman language, compare Proto-Tibeto-Burman *Iwaay 'buffalo', Jinghpaw ʼu-loi or ŋa-loi (ŋa 'bovine'), and Burmese ကျွဲ kywai < klway. Classical usagesKui frequently occurs in Chinese classic texts. Although some early texts are heterogeneous compositions of uncertain dates, the following discussion is presented in roughly chronological order. Early authors agreed that the mountain dragon-demon Kui had yizu 一足 "one foot" but disagreed whether this also applied to Shun's music master Kui. Since the Chinese word zu 足 ambiguously means "foot; leg" or "enough; sufficient; fully; as much as", yizu can mean "one foot; one leg" or "one is enough". "The Confucianists," explains Eberhard,[11] "who personified K'ui and made him into a 'master of music', detested the idea that K'ui had only one leg and they discussed it 'away'" (e.g., Hanfeizi, Lüshi Chunqiu, and Xunzi below). Instead of straightforwardly reading Kui yi zu 夔一足 as "Kui [had] one foot", Confucianist revisionism[12] construes it as "Kui, one [person like him] was enough." There is further uncertainty whether the mythical Kui was "one footed" or "one legged". Compare the English "one-footed" words uniped "a creature having only one foot (or leg)" and monopod "a creature having only one foot (or leg); a one-legged stand". ShujingThe Shujing uses kui 夔 in three chapters; Current Text chapters mention Shun's legendary Music Minister named Kui, and Old Text "Old Text" chapter has kuikui "grave; dignified". (New or Current Text and Old Text refer to different collections of Shangshu material with the Current Text being collected before the Old Text version. There is a long history of debate about the relative authenticity of the Old Text version as well as the dating of the constituent texts in both the Current and Old Text versions; see the article on the Shujing for more information.) First, the "Canon of Shun"[13] says the prehistoric ruler Shun appointed Kui as Music Minister and Long 龍 "Dragon" as Communication Minister.

Second, "Yi and Ji"[14] elaborates the first account.

Third, "The Counsels of the Great Yu"[15] uses kuikui 夔夔 "grave; dignified; awestruck" to praise Shun's filial piety for his father Gusou 瞽叟 (lit. "Blind Old Man"); "with respectful service he appeared before Gu-sou, looking grave and awe-struck, till Gu also became transformed by his example. Entire sincerity moves spiritual beings." Chunqiu and ZuozhuanThe (c. 6th–5th centuries BCE) Chunqiu and (early 4th century BCE) Zuozhuan use Kui as the name of a feudal state and of the legendary Music Master. The Chunqiu history records that in 634 BCE[16] the army of Chu destroyed Kui 夔; "In autumn, an officer of Ts'oo extinguished K'wei, and carried the viscount of K'wei back with them." Zuo's commentary notes the viscount of Kui, also written Kui 隗, was spared because the ruling families of both Chu and Kui had the same surname (see Guoyu below). The Zuozhuan for 514 BCE[17] provides details about Kui's raven-haired wife Xuanqi 玄妻 "Dark Consort" and their swinish son Bifeng 伯封.

GuoyuThe (c. 5th–4th centuries BCE) Guoyu uses kui 夔 as a surname and a demon name. The "Discourses of Zheng" (鄭語) discusses the origins of Chinese surnames and notes that Kui was the tribal ancestor of the Mi 羋 "ram horns" clan. Since Kui was a legendary descendant of the fire god Zhurong 祝融 and a member of the Mi clan, Eberhard explains,[11] he was a relative to the ruling clans of Chu and Yue. The "Discourses of Lu"[18] records Confucius explaining three categories of guai 怪 "strange being; monster; demon; evil spirit", including the Kui who supposedly resides in the 木石 "trees and rocks".

De Groot[19] says later scholars accepted this "division of spectres into those living in mountains and forests, in the water, and in the ground", which is evidently "a folk-conception older, perhaps much older, than the time of Confucius." For instance, Wei Zhao's (3rd century CE) commentary on the Guoyu:

XunziThe (early 3rd century BCE) Confucianist Xunzi mentions Kui twice. "Dispelling Obsession"[21] says, "Many men have loved music, but Kui alone is honored by later ages as its master, because he concentrated upon it. Many men have loved righteousness, but Shun alone is honored by later ages as its master, because he concentrated upon it." Another chapter (成相 [no translation available], 夔為樂正鳥獸服) says when Kui rectified music, the wild birds and animals submitted. HanfeiziThe (c. 3rd century BCE) Hanfeizi[22] gives two versions of Duke Ai 哀公 of Lu (r. 494–468 BCE) asking Confucius whether Kui had one leg.

Lüshi ChunqiuThe (c. 239 BCE) Lüshi Chunqiu uses kui 夔 several times. "Scrutinizing Hearsay"[24] records another version of Duke Ai asking Confucius about Kui's alleged one-footedness, and it states that Kui came from the caomang 草莽 "thick underbrush; wilderness; wild jungle".

One or two of "The Almanacs" in Lüshi Chunqiu mention kui. "On the Proper Kind of Dyeing"[25] mentions a teacher named Meng Sukui 孟蘇夔: "It is not only the state that is subject to influences, for scholar-knights as well are subject to influences. Confucius studied under Lao Dan, Meng Sukui, and Jingshu." "Music of the Ancients"[26] has two passages with zhi 質 "matter; substance" that commentators read as Kui 夔.

Note that the Lüshi Chunqiu says Kui was music master for both Yao and Shun, instead of only Shun. ZhuangziThe (c. 3rd–2nd centuries BCE) Daoist Zhuangzi mentions Kui in two chapters. "Autumn Floods"[27] describes Kui as a one-legged creature.

Burton Watson glosses Kui as "A being with only one leg. Sometimes it is described as a spirit or a strange beast, sometimes as a historical personage – the Music Master K'uei." "Mastering Life"[28] describes Kui as a hill demon in a story about Duke Huan of Qi (r. 685–643 BCE) seeing a ghost and becoming ill.

Shanhaijing The (c. 3rd century BCE – 1st century CE) Shanhaijing mentions both Kui 夔 "a one-legged god of thunder and rain" and kuiniu 夔牛 "a wild yak". The 14th chapter of the Shanhaijing, known as "The Classic of the Great Wilderness: The East" (大荒東經,[b] describes the mythical Kui "Awestruck", and says the Yellow Emperor made a drum from its hide and a drumstick from a bone of Leishen 雷神 "Thunder God" (cf. Japanese Raijin).

Groot[29] infers that the in "one-legged dragon" Kui, which was "fancied to be amphibious, and to cause wind and rain", "we immediately recognize the lung or Dragon, China’s god of Water and Rain". Carr interprets this cang 蒼 "dark green; blue" color "as a crocodile-dragon (e.g., Jiaolong) with its tail seen as 'one leg'", and cites Marcel Granet that the Kui's resemblance to a drum "is owing to drumming in music and dancing".[12] The account of Minshan Mountain (岷山, 崌山) in the 5th chapter of the Shanhaijing, the "Classic of the Central Mountains"[c] describes kuiniu "huge buffalo" living on two mountains near the source of the Yangtze River 長江 (lit. "long river").

The Shanhaijing commentary of Guo Pu describes kuiniu 夔牛 as a large yak found in Shu (present-day Sichuan). LijiThe (c. 2nd–1st century BCE) Liji mentions the music master Kui in two chapters. The "Record of Music"[30] explains. "Anciently, Shun made the lute with five strings, and used it in singing the Nan Fang. Khwei was the first who composed (the pieces of) music to be employed by the feudal lords as an expression of (the royal) approbation of them." The "Confucius at Home at Ease"[31] has Zi-gong ask whether Kui mastered li 禮 "ceremony; ritual; rites".

BaopuziGe Hong's (320 CE) Daoist Baopuzi 抱樸子 mentions kui 夔 in an "Inner Chapter" and an "Outer Chapter". "Into Mountains: Over Streams"[32] warns about several demons found in hills and mountains, including Kui 夔 with the variant name hui 暉 'light, brightness' (or hui 揮 'shake; wave' in some texts), "There is another mountain power, this one in the shape of a drum, colored red, and also with only one foot. Its name is Hui." "Breadth of Learning"[33] mentions two music masters, Kui 夔 and Xiang 襄 (from Qin), "Those who play the lute are many, but it is difficult to match the master of sounds of K'uei and Hsiang." Mythic parallels In addition to the Kui 夔, Chinese mythology has other uniped creatures. Based on "one-legged" descriptions, Carr compares kui with chi 螭 "hornless dragon; mountain demon" and hui 虺 "snake; python".[12] The Shanhaijing[34] mentions three one-footed creatures. The "Bellow-pot" bird "which looks like an owl; it has a human face but only one foot"; the "Endsquare" bird "which looks like a crane; it has one foot, scarlet markings on a green background, and a white beak"; and

Two other personages named Kui in Chinese folklore are Kui Xing 魁星 "the dwarfish god of examinations" and Zhong Kui 鍾馗 "the vanquisher of ghosts and demons". One-footed or one-legged Kui has further parallels in comparative mythology. For instance:

Notes

References

Footnotes

Further reading

External linksLook up 夔 in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia