|

Karen Jeppe

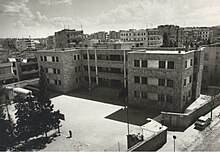

Karen Vel Jeppe (1 July 1876 – 7 July 1935) was a Danish missionary and social worker, known for her work with Ottoman Armenian refugees and survivors of the Armenian genocide, mainly widows and orphans, from 1903 until her death in Syria in 1935.[1] She was a member of Johannes Lepsius' Deutsche Orient-Mission (German Orient Mission)[2] and assumed responsibility (in 1903[3]) for the Armenian children in the Millet Khan German Refugee Orphanage after the 1895 Urfa massacres.[4] Work and activitiesBefore World War IIn 1902, Jeppe first heard about the persecutions of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, from her school headmaster H. C. Frederiksen (called also Friser) who presented an article written by Aage Meyer Benedictsen (1866–1927),[5] a Danish-Jewish-Icelandic linguist, writer, philologist and a secular antiimperialist intellectual.[6] Shortly after, she attended Benedictsen's lecture in Copenhagen, where he ended his talk by a cry for help to the Armenian people, passed on from an old Armenian. Benedictsen himself, was one of the first Danish cosmopolitans who was interested in the persecution of the Ottoman Armenians, and during one of his travels to Persia he visited the German Orient Mission in Urfa, which had started a school-orphanage, under the direct supervision of the German clergyman Johannes Lepsius. When Benedictsen returned to Denmark in 1902, he took the initiative to found the secular organization of the Danish Friends of Armenians ("Danske Armeniervenner" DA).[5] Deeply moved by Benedictsen's lecture, Jeppe was informed by him that Dr. Lepsius was just looking for a woman teacher for the school in Urfa. On 1 October 1903, she left home for a long journey across Europe and Asia Minor to arrive in Urfa (nowadays Şanlıurfa in Turkey), where she was welcomed by hundreds of Armenians, gathered to meet the newly arrived European lady.[5] Within a year, she learned Armenian, Arabic and Turkish, after which she started working at the school introducing new methods of teaching. In 1909, after the Adana massacres, Jeppe continued her work in providing the daily bread for the Armenians, buying a piece of land in the mountains, where she planted vineyards, and building up good relations with Kurds and Arabs. She was assisted by Misak Melkonian, a young Armenian orphan whom she had adopted.[7] During that period, Jeppe had also adopted Lucia, an orphan survivor of the Genocide.[5] During World War IAfter the outbreak of World War I, the Armenian genocide was conducted by the Young Turks. Jeppe tried to organize rescue efforts and help the Armenian refugees driven through Urfa, on their way to the death camps in the Syrian desert of Deir ez-Zor, providing food and water and hiding many of them under the floor of her house.[3][8][9] She never left Urfa during the war and helped many Armenians to escape by disguising them as Kurds and Arabs.[5][10] After World War I she was forced, due to ill-health, to return to Denmark in 1918, where she campaigned on behalf of Armenians. Jeppe in Aleppo After spending three years in Denmark, Jeppe decided to return to Syria. Upon her arrival at Aleppo in 1921, she found employment for Armenian widows by establishing orphanages, schools, medical clinics and workrooms, then worked to rescue two thousand Armenian women and children scattered in the area, as Aleppo director of the Commission for the Protection of Women and Children in the Near East.[3][11][12] It was set up under the auspices of the League of Nations to recover Armenian women and children who had been forcibly "absorbed" (a neutral term coined by Ara Sarafian - terms used contemporaneously included "kidnapped", "abducted", and "taken into slavery") into Turkish, Kurdish, and Bedouin households during the genocide, and to reintegrate them into the Armenian community. [13] However, the situation was deeply worsened in 1922, as new waves of Armenian refugees arrived in Aleppo escaping from the massacres in Cilicia, as the French troops -despite promises to the contrary- had evacuated Cilicia in 1921, leaving thousands of Armenians to be killed or expelled by Turkish nationalists.[5][14] In 1924, after negotiations with a wealthy Bedouin sheik, Hadjim Pasha, Jeppe rented parts of his lands to the west of Aleppo in the valley of the Euphrates, at a fair price.[15] In 1925, she was joined by two new assistants from Denmark; Jenny Jensen and Karen Bjerre who helped her to concentrate her efforts on this project. On the other hand, the French rulers in Syria had offered to create an agricultural colony for the Armenian refugees, but nobody joined in. The Armenians had lost confidence in the French rulers, after their withdrawal from Cilicia, which brought a fatal consequence to many of their compatriots.[5][16] Hadjim Pasha became a good friend of Karen Jeppe, helping her with practical things and maintaining the security of the new Armenian settlers through his status and the effect that he had in the region.[17] Life in the 1930s and death  Karen Jeppe made all efforts to create good relations between Bedouins and Armenian villagers, and she succeeded in founding six Armenian farming colonies in the region of Raqqa like Tel Armen, Tel Samen, Charp Bedros, Tineh, etc.[18] Jeppe visited Denmark for the last time in autumn 1933. Upon her return to Syria, she was affected by malaria. After a partial recovery, she continued directing her efforts towards the development of the newly created Armenian communities. In the summer of 1935, she suffered a more serious attack of malaria during her stay at her white house in the agricultural colony. She was taken to the hospital in Aleppo, where she died on 7 July 1935, at the age of 59.[5] She was buried in the Armenian cemetery of Aleppo.[19] Karen Jeppe has been described as the "Danish Mother of Armenians" by the Yerevan Golden Apricot International Film Festival.[20] The first Armenian high school in Aleppo (opened in 1947) is named after Karen Jeppe.[21] During the Syrian Civil War the school was closed and temporarily relocated to a safer region in Aleppo.[22] In 1927, Denmark bestowed the Medal of Merit in Gold (Danish: Fortjenstmedaljen i Guld) upon Jeppe.[23] See alsoNotes

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Karen Jeppe. |

||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia