|

June 2011 Christchurch earthquake

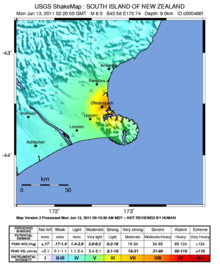

The June 2011 Christchurch earthquake was a shallow magnitude 6.0 Mw earthquake that occurred on 13 June 2011 at 14:20 NZST (02:20 UTC). It was centred at a depth of 7 km (4.3 mi),[1] about 5 km (3 mi) south-east of Christchurch,[7] which had previously been devastated by a magnitude 6.2 MW earthquake in February 2011. The June quake was preceded by a magnitude 5.9 ML tremor that struck the region at a slightly deeper 8.9 km (5.5 mi). The United States Geological Survey reported a magnitude of 6.0 Mw and a depth of 9 km (5.6 mi). The earthquake produced severe shaking, registering at VIII (Severe) on the Mercalli scale in and around Christchurch. It destroyed several structures and caused additional damage to many others which had been affected by previous earthquakes. The damaged tower of the historic Lyttelton Timeball Station collapsed before dismantling work could be completed. The earthquake downed phone lines and cut off power to 54,000 households. Restoration costs in Christchurch following the February earthquake were estimated to increase by NZ$6 billion (US$4.8 billion) because of the additional damage from this event. Forty-six people suffered injuries, two of which critical, and one elderly man died after being knocked unconscious. BackgroundNew Zealand lies along the boundary between the Australian and Pacific plates. In the South Island most of the relative displacement between these plates is taken up along a single dextral (right lateral) strike-slip fault with a major reverse component, the Alpine Fault. In the North Island the displacement is mainly taken up along the Kermadec subduction zone, although the remaining dextral strike-slip component of the relative plate motion is accommodated by the North Island Fault System (NIFS).[8] A group of dextral strike-slip structures, known as the Marlborough fault system, transfer displacement between the mainly transform and convergent type plate boundaries in a complex zone at the northern end of the South Island.[9] This zone of deformation is now known to be expanding south and east into the Canterbury region. Beneath the northern and eastern Canterbury Plains, a series of active SW-NE trending thrust faults have been recognised, linked by W-E trending strike-slip faults that at least in part reactivate Cretaceous age extensional faults.[10] New Zealand has a history of earthquakes. Since the European settlement, the largest on record was a magnitude 8.2 ML major earthquake that occurred on 23 January 1855 near the Wairarapa plains of the North Island.[11] Another destructive magnitude 7.8 ML earthquake struck the region near Hawke's Bay on 3 February 1931; it is the deadliest earthquake recorded in the country to date, greatly affecting much of Napier and Hastings.[12] In comparison, the South Island has experienced fewer large earthquakes. The magnitude 7.1 Mw event of 4 September 2010 produced by far the strongest ground motions ever recorded in the Canterbury region,[13] triggering a large number of aftershocks. Although similar aftershock sequences have historically occurred around the world, such occurrences were extremely unusual in the region, which had shown low levels of seismic activity for thousands of years. The event has led to the discovery of previously dormant geological faults across central-eastern South Island, in particular beneath regional plains and the adjacent seabed.[14] Earthquake The magnitude 6.0 Mw earthquake occurred inland on 13 June 2011 at 14:20 NZST, (02:20 UTC) at a shallow depth of 7 km (4 mi),[1] about 5 km (3 mi) to the south-east of Christchurch, New Zealand.[7] Owing to the interaction of the major Pacific and Australia Plates, much of the regional plate boundary along central South Island is characterised by land deformation. The earthquake was a direct result of strike-slip faulting at the eastern end of the rupture zone of a strong magnitude 6.2 MW earthquake, which occurred on 22 February 2011 along the Port Hills Fault.[15] The June earthquake was preceded by a magnitude 5.9 ML tremor with a similar focal mechanism that struck 1 hour and 20 minutes earlier.[16] Experts believe the quakes were triggered by a previously undiscovered fault in the region, located several kilometres south of the Port Hills Fault.[17] The United States Geological Survey reported a magnitude of 6.0 Mw and a focal depth of 9 km (5.6 mi) for the earthquake, while the precursor tremor was assigned a magnitude of 5.2 Mw at a similar depth.[18][19] Seismologists reported that the earthquakes were part of a prolonged aftershock sequence associated with the major magnitude 7.1 earthquake of September 2010, which includes the February 2011 event.[15] They were succeeded by multiple lighter aftershocks; the strongest, a moderate magnitude 5.1 ML struck a minute after the event. Another tremor 5.0 ML struck the region two days later.[20] Despite significant energy release, the earthquakes were believed to have increased the risk of an additional aftershock of similar magnitude; calculations from GNS Science indicated a 23 percent probability of a magnitude 6.0–6.9 ML earthquake occurring in the Canterbury aftershock zone within the 12 months following the event.[17] Weeks later, a magnitude 5.4 ML tremor jolted Christchurch overnight on 22 June, causing additional damage and prompting evacuations.[21] Focused only several kilometres below the surface, the earthquake resulted in significant shaking over a large portion of central-eastern South Island. Maximum ground motions registered at VIII (Severe) on the Mercalli intensity scale in Christchurch, while strong shaking (MMI VI) was felt in adjacent populated areas such as Rolleston and Lincoln. The landforms of Sumner recorded intensified shaking due to the effects of its topographic setting.[22] Widespread lighter motions were observed throughout much of the remaining region,[23] with slight property damage reported from as far afield as Dunedin. The earthquake was felt as far away as New Plymouth and Invercargill.[3] Damage, casualties and effects  The earthquake and the precursor tremor struck during the afternoon near a populated area, where most buildings had been left in precarious conditions by the February 2011 event. The June earthquake affected roughly 400,000 people, most of whom may have experienced strong (MM VI) shaking.[23] It caused damage to buildings and infrastructure alike, collapsing or otherwise destroying several homes.[24] There were at least 46 injuries: falling debris struck several people, and two others were hospitalised in critical condition.[6] In the city centre, two workers were brought to hospital after being rescued from a collapsed church. The following morning, officials confirmed the death of an elderly man who had been knocked unconscious from a fall in his nursing home.[5][25] In the wake of the earthquake, multiple phone lines were down, and scattered power outages affected about 54,000 households. The tremor had damaged 70 underground 11,000 volt cables, contributing to the outages,[26] and ruptured water mains, resulting in widespread street flooding.[27] Officials ordered the precautionary closure of bridges in the area,[28] as one bridge had already succumbed to the strong shaking.[27] Several days after the tremor, dislodged electrical wiring from the ongoing aftershocks sparked a small fire in a control panel at Christchurch Hospital.[29] Strong ground motions caused many secondary effects, including gas leaks and widespread soil liquefaction.[27] Consequently, sand boils emerged from asphalt roads, toppling a few cars and sinking another.[30] Several houses in the hill suburbs of Sumner and Redcliffs were affected by falling boulders from hillsides. Many parts of Christchurch lost water pressure, and residents were urged to be conservative in their water use.[31] In some parts of the Heathcote Valley, previously dormant or non-existent natural springs surfaced because of a sudden rise in the water table, flooding some properties.[32] Socioeconomic impactThe NZX 50 Index fell by 0.4 percent to its lowest level since 20 April.[33] In addition, the New Zealand dollar declined in the wake of the disaster, dropping by nearly 0.01 US dollar, or about 1.3%.[34] Following a dramatic decline in event numbers, Vbase, a venue management company, disemployed 151 of its full-time staff.[35] Nationwide, building consents tumbled considerably, further dropping by 4.5% in the wake of the aftershock.[36] The earthquake's impact extended beyond national grounds; in light of its occurrence, Insurance Australia Group reported a net claim loss of A$65 million (US$61.5 million).[37] Damage evaluationThough the exact extent of the losses was unclear, the earthquake caused additional damage to many previously affected structures in Christchurch; around half of the buildings in the city centre had already damaged or destroyed by previous earthquakes.[38] Preliminary assessments found that over 100 additional buildings had been rendered beyond repair.[39][40] Despite its moderate magnitude, the preceding magnitude 5.6 ML tremor caused several two-story buildings at a road intersection to collapse.[41] Multiple hospitals and residential care facilities in Christchurch were left without essential services, and some even reported considerable infrastructural damage.[42] Despite earlier renovation attempts, authorities were considering the complete demolition of the 130-year-old Christchurch Cathedral. The building had become structurally compromised due to its collapsed western wall, and the strong vibrations had shattered its stained glass rose window.[43] The Christchurch Arts Centre sustained similar damage, though it had been in a precarious state prior. A three-month reconstruction project was scheduled to start in October 2011, with an estimated total cost of NZ$30 million (US$24 million).[44] The tower of the historic Lyttelton Timeball Station, which endured damage from the February 2011 earthquake, collapsed before dismantling work on the building could be completed.[45] Lyttelton Port, a major harbour in the region, suffered additional damage from the tremors and underwent full engineering assessments.[46] The multi-story HSBC Tower shook considerably during the quake, but damage was limited to cracks and broken roof tiles.[47] Artefacts from the Canterbury Museum collection were thrown into disorder by the aftershocks, several days after reordering work following the February 2011 earthquake had been completed.[39] In all, experts estimated the earthquake would increase reconstruction costs in Christchurch by about NZ$6 billion (US$4.83 billion).[48] ResponseIn light of the possibility of aftershocks, police evacuated shopping malls and office buildings around the city. Essential organisations in the area were evacuated as a safety precaution, including the police headquarters and offices of the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority.[49] At Christchurch International Airport, officials halted operations after the earthquake, but all flights resumed later that day.[31] Months before the event, a severe magnitude 6.2 earthquake occurred in a similar area adjacent to Christchurch, causing widespread destruction and fatalities in the city. Concerns arose about the condition of previously damaged structures, and the 13 June earthquakes caused further distress among many victims.[27] Dozens of dissatisfied residents were expected to move out of the city, and many others sought professional help for anxiety and depression-related issues.[50][51] Relief effortsIn the immediate aftermath of the earthquakes, the National Crisis Management Centre was activated through The Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management to manage public response to the disaster;[49] hundreds of police officers were accordingly dispatched to patrol the city streets. Authorities proposed to set up an outdoors emergency operations centre, as well as a public welfare centre to provide shelter to victims overnight.[31] The Student Volunteer Army – which partook in silt shifting after the February 2011 quake – again prepared the recruitment of participants to initiate street clearing actions.[52] A total of NZ$285,000 (US$230,000) was allocated for donations to nine charities, including NZ$40,000 (US$32,000) to both the Red Cross Christchurch earthquake appeal and the Canterbury Earthquake Appeal Salvation Army funds.[52] At Westpac Bank, a public donation account was opened in order to provide financial assistance for earthquake victims.[53] Chief executives from the Commonwealth Bank sponsored an exclusive dinner in Sydney to raise money for rebuilding costs; an initial A$700,000 (US$660,000) was allocated prior to the event, with entry costs of A$10,000 (US$9,500) per ticket.[54] See also

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia