|

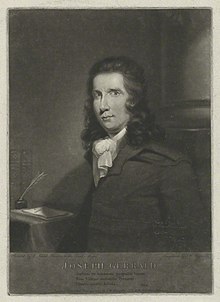

Joseph Gerrald

Joseph Gerrald (9 February 1763 – 16 March 1796)[1] was a political reformer, one of the "Scottish Martyrs". He worked with the London Corresponding Society and the Society for Constitutional Information and also wrote an influential letter, A Convention the Only Means of Saving Us from Ruin. He was arrested for his radical views and convicted of sedition in 1794. Subsequently, he was deported to Sydney, where he died from tuberculosis in 1796. Early and family lifeGerrald was born in St. Kitts, West Indies to Joseph Gerrald, a wealthy Irish planter, and Ann Rogers. In 1765, Gerrald and his family moved to London, where he attended a boarding school in Hammersmith until he was 11. Gerrald's mother died when he was very young – shortly after his family moved to England, and his father died when he was just 12 years old. After his father died in 1775, Gerrald was sent to study at Stanmore school under Dr. Samuel Parr. While at Stanmore, Gerrald performed very well in several subjects, such as Greek, Latin, and art, and became very close with Parr. Despite these successes, Parr needed to expel Gerrald because of 'extreme indiscretion'. In 1780, Gerrald moved back to the West Indies to tend to matters of the family fortune. Unfortunately, his father had been lavishly spending and had reduced the family estate considerably. During his stay, he brashly married a woman and they had a son and daughter together. Gerrald's wife died soon after the birth of the second child and he was left to raise two young children without much money. He then decided to move to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where he was a lawyer for several years. In 1785, he was listed in the muster roll for the City of Philadelphia, in the 3rd company 6th battalion of the Philadelphia militia.[2] Gerrald returned to London in 1788, but in 1789 he moved to Bath due to his declining health.[1] Political reformerAfter Gerrald's return to England, he began writing anonymous letters about politics and joined the Society for Constitutional Information and the more radical London Corresponding Society. He became popular among radical reform groups due to his eloquence and pleasant demeanor.[1] These groups were under continuous observation by royal authorities due to their promulgation of radical ideas; these ideas, in conjunction with eruption of war all over Europe during the 1790s, raised fears of a similar revolution in Britain. Gerrald was mostly concerned with parliamentary reform and was a large proponent of a national convention, alongside Thomas Paine. The convention would be democratically elected and would focus on sorting out the laws of England. Gerrald drew his ideas from the successful precedent of the Saxons' Convention, and outlined his plans in his pamphlet, A Convention the Only Means of Saving Us from Ruin (1793).[3] A Convention the Only Means of Saving Us from RuinGerrald sets the tone of the letter by discussing how legislators and the government may be offended by the criticisms he presents, but states that the government exists to represent the people and should learn from their suggestions. He draws on the trajectories and repercussions of the wars of the 18th century, including the American Revolution, to form his argument that the British should not have engaged in the current war, which Prime Minister William Pitt was carrying through. Throughout this pamphlet, Gerrald addresses the people of England on the need for common folk to be involved in politics. He believed that this was important because of the eruption of war between England and France, caused by the majority British opposition to French Revolution. He argues that even though the government declares war, it is made possible only because of the contributions of others – in the form of taxes and soldiers – and thus that people are morally obliged to understand and justify the wars. On this front, Gerrald uses the young United States, an example showing that there exists a country that doesn't go to war unless its citizens decide to. Gerrald also found civic involvement necessary because the wars themselves were not constructive. He suggests that negotiations could have made a larger impact on the people because the outcomes of the wars left civilians in a worse state than they had started with. In addition, he refers to the Society of the Friends of the People's report that many current representatives are self-elected or are tools for the aristocracy, and that the current system favors neither wealth nor population size. To overcome these issues, Gerrald suggests a plan where people can elect representatives who will follow instructions set by the general body.[4] Plans for the conventionThe convention will have 250 deputies from England and 125 from Scotland and these 375 men will speak out for the welfare of both England and Scotland. Any male can be elected to the convention unless a jury has found him to be a criminal, idiot, or lunatic. In order to determine the deputies in the convention, there will first be a primary assembly for each parish, 1250 in total. In this assembly, any males that are 21 and over and not deemed a criminal, lunatic, or idiot can vote. The members of the parish will vote for ten members to form a second assembly composed of the elected individuals from ten parishes. Each second assembly will then choose two deputies for the national convention. This process results in every deputy representing 5000 males each. Gerrald argues that because the deputies are elected with the specific purpose of speaking for their constituents, the people will have more political liberty while politics will have less corruption. He also states that war will be eliminated, as people will now have a voice in the declaration of it.[4] London Corresponding SocietyOn October 24, 1793, Gerrald and Maurice Margarot were chosen as delegates for a convention of reformers, the British Convention of the Delegates of the People, in Edinburgh.[5] While attending, Gerrald took a trip to the Scottish countryside to publicize the reform movement. This convention was considered incendiary because of its goals of universal suffrage and annual parliaments and Gerrald's participation in the convention is what led to his arrest.[1] Arrest and convictionThe aims of the British Convention were moderate, but Gerrald and others were arrested and in March 1794 he was tried for sedition. It was felt that the case was prejudiced, and while out on bail Gerrald had been urged to escape by his friends such as Dr. Parr, but he considered that his honour was pledged. At his trial in Edinburgh he made an admirable speech in defence of his actions but was condemned to 14 years transportation. The apparent courtesy and consideration with which the trial was conducted could not conceal the real prejudice which ruled the proceedings. Throughout the trial, Gilbert Wakefield provided Gerrald with moral support.[6] Gerrald was imprisoned in London until May 1795, when he was hurried on board the storeship Sovereign about to sail for Sydney. He arrived there on 5 November 1795. He was then in a poor state of health suffering from tuberculosis and was allowed to buy a small house and garden in which he lived. He died on 16 March 1796.[5] LegacyGerrald was a man sustained by his belief in the rights of mankind. In the account of his death David Collins speaks of his "strong enlightened mind" and that he went to his death "glorying in being a martyr to the cause which he termed that of Freedom and considering as an honour that exile which brought him to an untimely grave".[7] He was buried in the plot of land he had bought at Farm Cove. His son, Joseph, was cared for by Dr. Parr. Gerrald's associates included Thomas Muir, Thomas Fyshe Palmer, William Skirving and Maurice Margarot.[5] His name appears on the Political Martyrs' Monument (1844) on Calton Hill at Edinburgh and a similar monument at Nunhead Cemetery (1852) in London.[1] Gerrald's son Joseph was admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1800 at the age of 17.[8] See alsoCitations

|

||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia