|

Jorge Juan y Santacilia

Jorge Juan y Santacilia (Novelda, Alicante, 5 January 1713 – Madrid, 21 June 1773) was a Spanish mariner, mathematician, natural scientist, astronomer, engineer, and educator. He is generally regarded as one of the most important scientific figures of the Enlightenment in Spain. As a military officer, he undertook sensitive diplomatic missions for the Spanish crown and contributed to the modernization and professionalization of the Spanish Navy. In his lifetime, he came to be known as el sabio español ("the Spanish savant"). His career as a public servant constitutes an important chapter in the Bourbon Reforms of the 18th century. As a young naval lieutenant, Juan participated in the French Geodesic Mission to the Equator of 1735–1744, which established definitively that the shape of the Earth is an oblate spheroid, flattened at the poles, as predicted in Isaac Newton's Principia. With his fellow lieutenant Antonio de Ulloa, Juan travelled widely in the territories of the Viceroyalty of Peru and made detailed scientific, military, and political observations of the region. They also helped to organize the defense of the Peruvian coast against the English squadron of Commodore Anson, after the outbreak of the War of Jenkins' Ear in 1739. After returning to Spain in 1746, Juan became a protégé and collaborator of the Marquess of Ensenada, a leading minister under King Ferdinand VI. Under Ensenada's orders, Juan undertook an eighteen-month mission of industrial espionage in London, after which he worked tirelessly to modernize and professionalize naval architecture and other operations in Spain. Juan's influence declined somewhat after Ensenada fell from power in 1754. In 1760 Juan was appointed as Squadron Commander, the most senior officer in the Spanish Navy, but ill health soon forced him to give up that role and instead take up diplomatic and educational missions. As a mathematician and educator, Juan promoted the study and application of the infinitesimal calculus at a time when the subject was not taught in Spanish universities. He served as ambassador plenipotentiary to the Sultan of Morocco in 1766–1767, and as director of the Seminary of Nobles of Madrid from 1770 until his death in 1773. Family and education Jorge Juan was born of two distinguished hidalgo families: his father was don Bernardo Juan y Canicia, a relative of the Counts of Peñalba, while his mother was doña Violante Santacilia y Soler de Cornellá, who came from a prominent land-owning family in Elche. Both of his parents were widowed and had several children from their respective first marriages. Jorge Juan was born in a home in the estate El Fondonet (also known as El Hondón, in Castilian), owned by his grandfather don Cipriano Juan Vergara and located in Novelda, a town in the province of Alicante. He was baptised in the church of the neighboring town of Monforte del Cid. The family lived in a home on the Plaza del Mar in the city of Alicante and vacationed in Novelda. As a younger son, Jorge was not expected to inherit his father's estate. His family therefore intended him for a career in the military or the church, as was customary for younger sons of noble families. In fact, Jorge had been baptized in the parish of Monforte, rather than that of Novelda (his actual place of birth) in order to render him eligible for a benefice attached to the Collegiate Church of Saint Nicholas, in Alicante, should he eventually pursue an ecclesiastical career. His paternal uncle Antonio Juan was a canon of that church. His father Bernardo died when Jorge was only two years old.[1] Jorge received his first education at the Jesuit school in Alicante, under the supervision of his uncle, the priest Antonio Juan. Another of Jorge's paternal uncles, Cipriano Juan, was the bailiff of Caspe in the Order of Malta (also known as the "Order of Saint John", or the "Knights Hospitaller"). Cipriano eventually took charge of the education of the young Jorge, sending him to study grammar in Zaragoza as preparation for higher education. Knight of Malta Through Cipriano's influence, Jorge was admitted to the Order of Malta at the age of twelve. This required him to show that all four of his grandparents were of noble birth, by proving their armigerous status and "purity of blood". The young Jorge Juan then traveled to the island of Malta to serve as page to Grand Master António Manoel de Vilhena. "Hospitaller Malta" was at that time a vassal state of the Kingdom of Sicily, ruled by Habsburg emperor Charles VI. Juan stayed in Malta for nearly four years. There he took religious vows as a Knight of Saint John, which imposed upon him the requirement of lifelong celibacy. He took the first steps in his naval career by sailing in warships of the Order's navy. In 1729, at the age of sixteen, Juan received from the Grand Master the title of Commander of Aliaga (Comendador de Aliaga), a rank that he held for the rest of his life and which provided him with a benefice. Spanish navyJuan then returned to Spain and applied for admission to the Royal Company of Marine Guards, the Spanish naval academy, located in the port city of Cádiz. He entered the academy in 1730 and proceeded to study modern technical and scientific studies subjects such as geometry, trigonometry, astronomy, navigation, hydrography, and cartography. He also completed his education in the humanities with lessons in drawing, music, and dancing. He earned a reputation as a brilliant student and his fellow students nicknamed him "Euclid". As a naval cadet (guardia marina), Juan participated in the successful expedition against Oran. He finished his studies at the academy in 1734 and took part in the Battle of Bitonto against the Austrians in the Kingdom of Naples. Juan remained in the service of the Spanish Navy (the Armada) for the rest of his life. Sojourn in South AmericaIn light of the long-running debate between Cartesians and Newtonians over the figure of the Earth, the French Academy of Sciences decided to sponsor two geodesic expeditions: one to measure the arc length corresponding to one degree of latitude near the equator, and the other to carry out a similar measurement near the Arctic Circle. The only feasible location for the equatorial expedition was in the territory of the Audiencia of Quito, in what is now the country of Ecuador. At the time, this was part of the Viceroyalty of Peru under the Spanish Crown. In 1734, King Philip V of Spain agreed to allow the French expedition to carry out its work in Quito, under the condition that the French scientists should be joined by two Spanish naval officers capable of understanding and collaborating with the scientific work involved. Upon the recommendation of his First Secretary of State José Patiño, Philip appointed to that role Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, who were then 21 and 18 years old, respectively. The two were promoted to the rank of naval lieutenant (teniente de navío) so that they would have the appropriate seniority for the mission.[2] The equatorial expedition was led by three members of the French Academy of Sciences: the astronomer Louis Godin, and geographers Charles Marie de La Condamine and Pierre Bouguer. Their collaborators included the physician and naturalist Joseph de Jussieu and the engineer Jean-Joseph Verguin.[3] On 26 May 1735, Juan and Ulloa left Cádiz in the company of the Marquess of Villagarcía, who had been appointed as the new Viceroy of Peru. They met the French scientists at the Caribbean port of Cartagena de Indias, on the mainland of South America. They then sailed together to Portobelo, crossed the Isthmus of Panama, and proceeded by boat to the Pacific port of Guayaquil. Juan and Ulloa then traveled inland with Godin, reaching the city of Quito in May of 1736. The Arctic expedition was led by Pierre Louis Maupertuis and carried out its measurements in 1736–1737 in a part of Lapland that belonged at the time to the Kingdom of Sweden. Meanwhile, the mission to the equator, which had been organized first, proved much more challenging and took almost ten years to complete. Its members had to contend with the harsh climate and topography of the region, the prevalence of tropical diseases, and the suspicions of the local population and authorities. The geodesic work around the equator finally began in September 1736 with the measurement of the distance between two base points chosen to lie on the plain of Yaruquí, outside the city of Quito. Those points then served as baseline for the triangulation with which the members of the mission measured an arc of about three degrees of latitude that extended to the south, past Riobamba and up to an endpoint near the city of Cuenca.  In 1737, a personal dispute between Ulloa and the new president of the Audiencia de Quito, Joseph de Araujo y Río, caused Araujo to order the arrest of both Ulloa and Juan, while announcing his intention to have them killed.[4] The young officers took refuge in a church and Ulloa then escaped through the cordon of Araujo's men, reaching Lima and obtaining the protection of the Viceroy.[4] In 1739 surgeon Jean Seniergues, one of the French members of the mission, was killed by a mob in the bullring in Cuenca.[2]  After the War of Jenkins' Ear broke out between Spain and Great Britain in 1739, Juan and Ulloa were called upon to help organize the defense of the Peruvian coast.[4] Commodore Anson had set out in from England in September of 1740 with orders to sail around Cape Horn and then attack Spanish ships and settlements along the Pacific coast. Anson successfully circumnavigated the globe in 1740–1744, but in Peru his only significant action was the attack against the town of Paita, which was plundered and burned in November 1741. Their military responsibilities due to the war with Britain kept Juan and Ulloa from scientific work for long periods and further delayed the completion of the geodesic measurements. La Condamine was eager to mark the two base points of the triangulation with permanent monuments. In 1740 he began to erect these, each in the form a pyramid above a square base. This initiative, however, soon led to a dispute between the French and Spanish scientists. One source of contention was the inclusion of an ornament in the shape of a fleur-de-lis (the traditional symbol of the French monarchy) at the apex of the pyramid. Juan and Ulloa also objected to the proposed inscription, which named only the three scientists who were members of the French Academy of Sciences: Godin, Bouger, and La Condamine. The young Spanish officers then rejected La Condamine's offer to list their names as "assistants" or "auxiliaries", leading to protracted lawsuits in the Spanish courts that were not resolved before all of the members of the mission had returned to Europe.[5] The corregidor of Cuzco, Diego de Esquivel y Navia, wrote to La Condamine in 1742 that

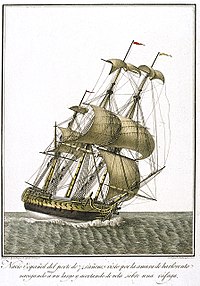

Despite this dispute, La Condamine continued to express high regard for the skills of the two Spanish officers and for their contribution to the mission. All of the topographical and astronomical measurements were concluded towards the end of 1742, and by March 1743 the members of the mission agreed on the result that they had been seeking: one degree of latitude around the equator corresponded to an arc length of 56,753 toises.[2] Together with the work of the Arctic expedition led by Maupertuis and with geodesic measurements carried out in France, this established unequivocally that the Earth is an oblate spheroid, i.e. flattened at the poles, as Newton had predicted. During the mission, Juan also successfully used a barometer to measure the heights of several of the peaks of the Andes, based on the formulas developed for that purpose by Edme Mariotte and Edmond Halley.[1] Return to SpainAt the end of 1744, Juan and Ulloa embarked for Europe on two different French ships, each carrying their own copies of their scientific and other papers, in order to minimize the risk that their work would be lost in the homeward journey. At the time, Great Britain was at war with both France and Spain, and Ulloa's ship was captured by the British Navy. Initially held as a prisoner of war in Portsmouth, Ulloa's scientific work attracted the attention of the new First Lord of the Admiralty, the Duke of Bedford. Bedford allowed Ulloa to travel to London, where Ulloa was elected as fellow of the Royal Society. Thank to the intervention of the President of the Royal Society, Martin Folkes, Ulloa was eventually allowed to continue on to Spain. Juan, for his part, landed safely in Brest on October 1745. Juan then travelled to Paris, where his contribution to the Geodesic Mission was rewarded by election as corresponding member of the French Academy of Sciences. Juan finally arrived in Spain at the start of 1746, a few months ahead of Ulloa.[1] They were both promoted to the rank of frigate captain (capitán de fragata).  Juan and Ulloa jointly published several works based on their South American observations. Juan, who was the more mathematically inclined of the two, was largely responsible for writing the Astronomical and Physical Observations Made by Order of His Majesty in the Kingdoms of Peru, which contained his calculations of the figure of the Earth. The publication of the book was held up by the Spanish Inquisition because Juan worked within the framework of the heliocentric cosmology, which the Catholic church still officially regarded as heretical after the condemnation of Galileo more than a century earlier.[1] The Inquisition allowed the publication of the book to proceed in 1748, after Juan modified the text to present heliocentrism as a hypothesis adopted for purposes of calculation. Ulloa, for his part, wrote most of the four volumes of the Historical Report of the Voyage to Southern America, which also appeared in 1748. Both authors collaborated in the composition of the Historical and Geographical Dissertation on the Demarcation Meridian between the Dominions of Spain and Portugal, published in 1749.[1] The purpose of that work was to determine precisely the line of demarcation as defined by the terms of the Treaty of Tordesillas between Spain and Portugal, signed in 1494 under the sponsorship of Pope Alexander VI. Juan and Ulloa also jointly signed a confidential report, written by Ulloa around 1746 and addressed to the Marquess of Ensenada, a powerful minister in the new government of Ferdinand VI. That report, titled Discourse and Political Reflections on the Present State of the Kingdoms of Peru, remained unknown to the public until it was published in London in 1826 by an otherwise obscure Englishman, David Barry, under the title Noticias secretas de América ("Secret News from America").[6] That report paints a dire picture of the social and political situation of the Viceroyalty of Peru in 1730s and 1740s, alleging many grave instances of lawlessness and mismanagement by the civil and church authorities in the region. It also denounces in very strong terms the exploitation of the Native American population by unscrupulous governors (especially the corregidores) and priests (especially the members of the mendicant orders). The importance and reliability of that confidential report have been subjects of enduring controversy among historians of Spanish America.[6] Espionage and naval architecture In March of 1749, the Marquess of Ensenada gave Juan a sensitive mission of industrial espionage in England. Juan traveled to London incognito as "Mr Joseus", communicating back to Ensenada using a numerical cipher. Juan's principal task was to learn about the design of the latest British warships and to recruit some of the constructors in order to help the Spanish Navy to improve its outdated fleet. He was also tasked with collecting information about the English manufacture of fine cloth, sealing wax, printing plates, dredges, and armaments, to purchase surgical instruments for the Royal College of Naval Surgeons, in Cádiz, and to procure steam engines to pump water out of mines. In London, Juan befriended Admiral Anson and the Duke of Bedford. In November 1749 he was elected fellow of the Royal Society.[7] With the help of a Catholic priest, Father Lynch, Juan was able to recruit about fifty naval artisans and workmen who defected to Spain. Some of these men, such as Matthew Mullan and Richard Rooth, went on to build the Spanish ships that would later fight in the American Revolutionary War and at the battle of Trafalgar. In 1750, Juan was elected as member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences upon the recommendation of its director, Pierre Louis Maupertuis. Maupertuis had been one of the key figures in the determination of the figure of the Earth from geodesic measurements and was therefore aware of Juan's contribution to that effort and of his mathematical skills. After eighteen months in England, Juan finally fled the country to avoid arrest as a foreign spy. Back in Spain, Juan was promoted to the full rank of captain (capitán de navío). The Marquess of Ensenada then put him in charge of all naval construction. Juan established his own system of shipbuilding, approved by the authorities in 1752. He carried out major improvements of the military shipyards, including those in Cartagena, Cádiz, Ferrol, and Havana. He implemented a modern industrial system of division of labor among the different disciplines involved in the construction of warships, such as dry-docks, shipyards, furnaces, rigging, and canvas making. Juan also modernized the armaments used by the navy. Juan was chiefly concerned to build ships with the least possible expenditure of wood and iron consistent with the vessel's stability. Among the warships built under Juan's "English system" were the Oriente (1753) and the Aquilón (1754). However, after the Marquess of Ensenada fell from power in 1754, Juan's "English system" started to be abandoned in favor of the "French system" promoted by Julián de Arriaga, the new Secretary of the Navy. Scientific and educational efforts During Juan's lifetime, the universities in Spain were wholly controlled by the Catholic Church and offered no modern scientific instruction. Juan promoted the teaching of differential and integral calculus in the Spanish military academies and helped to supply those institutions with modern scientific equipment.[1] In 1752, the King appointed Juan as Captain of the Royal Company of Marine Guards (Capitán de la Real Compañía de Guardias Marinas), which effectively put him in control of the Naval Academy in Cádiz. Juan appointed the French astronomer Louis Godin, with whom he had worked during the mission in South America, as director of the Academy. Together, in 1753 Juan and Godin established Spain's first astronomical observatory, the Royal Naval Observatory, based in Cádiz.[1] In 1757, Juan published a new textbook, the Navigational Compendium, for the instruction of the Academy's cadets. Juan was corresponding member of the French Academy of Sciences (since 1745), fellow of the Royal Society of London (since 1749), and member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences (since 1750). In 1755, Juan founded the Asamblea Amistosa Literaria de Cádiz ("Friendly Literary Assembly of Cádiz"), which for several years met every Thursday to discuss various intellectual subjects, and which was composed principally of teachers of the Naval Academy. Juan's goal was to lay the groundwork for the future establishment of a Spanish Academy of Sciences, something that came about only in 1847, long after Juan's death. Juan was made a member of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, in Madrid, in 1767, based on his contribution to architecture.  In 1770, King Charles III appointed Juan as director of the Seminary of Nobles in Madrid. That institution had been created in 1725 by Philip V to train the children of Spain's aristocracy in military and civil administration, but it had declined after the expulsion of the Jesuits (who had been in charge of the Seminary) in 1767. As its director, Juan succeeded in overhauling the faculty, modernizing the curriculum, and increasing the student enrollment.[1] Juan's principal scientific work was the Maritime Examination, published in two volumes in 1771. That work was principally concerned with practical naval architecture, but it also contained Juan's own original work on the theory of water's resistance to a ship's motion and of the generation of shock waves.[1] Juan criticized Leonhard Euler's theory of fluid resistance, which was based on the impact of the water flow upon the ship's solid surface, and proposed an alternative based on the action of gravity.[8] Both Euler's and Juan's theories were eventually found to be incorrect and have been superseded by the modern theory based on viscosity. Further military and diplomatic appointmentsIn 1760 Juan was appointed as Squadron Commander of the Royal Navy (Jefe de Escuadra de la Real Armada), making him the most senior Naval officer in Spain. Shortly after that, however, Juan began to suffer from a biliary colic that forced him to retire temporarily to the spa at Busot, in his native province of Alicante. In 1766–67, he served as ambassador plenipotentiary to the Sultan of Morocco, Mohammed ben Abdallah, for the purpose of concluding the negotiation of a peace treaty between Spain and Morocco. After accomplishing that mission, Juan returned to Madrid. In 1768, Juan was again forced to seek relief for his health ailments, this time at the baths in Trillo. His last official appointment was as director of the Seminary of Nobles in Madrid. Death and posterity Jorge Juan died in Madrid in 1773 at the age of 60. His reported symptoms, including muscle stiffness and seizures, may have resulted from a cerebral amebic infection. He was buried in the church of San Martín. In 1860 he was re-buried in the Pantheon of Illustrious Sailors in Cádiz. Among other posthumous honours, a mayor street in the Salamanca district of Madrid and a Churruca-class destroyer of the Spanish Navy were named after him.[9] In the last series of peseta banknotes (the Spanish currency before the adoption of the euro in 2002), the highest denomination bill (10,000 pesetas) carried Juan's portrait on the reverse side. Works

In collaboration with Antonio de Ulloa

References

Further sources

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Jorge Juan. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia