|

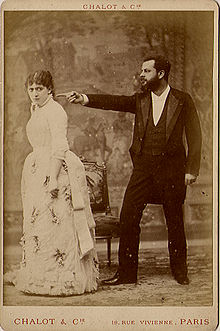

Jacques Damala

Aristides Damalas (Greek: Aριστεíδης Δαμαλάς, alternative spellings Aristidis or Aristide; 15 January 1855 – 18 August 1889), known in France by the stage name Jacques Damala, was a Greek military officer-turned-actor, and husband of Sarah Bernhardt in his last years. Damala's characterisation by modern researchers is far from positive. His handsomeness was as notable as his insolence and Don Juan quality. Writer Fredy Germanos describes him as an opportunistic and hedonistic person, whose marriage to the great diva would inevitably intensify and maximise his vices, namely, his vanity and obsession with women, alcohol, and drugs. Diplomatic career and notorious social life Damala was born at Piraeus, Greece on 15 January 1855[1] to the noble Damalas family. He was the second of three children of Ambrosios Damalas (2 June 1808 – 29 July 1869), a wealthy shipping magnate, who later served as mayor of Ermoupoli and Piraeus and his wife, Calliope Ralli (6 June 1829 – 14 February 1891), whose father, Loukas Rallis, had also once served as mayor of Piraeus and Ermoupolis, Syros (he had also came up with the name "Ermoupoli") and was a member of the Executive Committee which attempted the liberation of Chios in 1827, during the Greek War of Independence. The other children of Ambrouzis and Calliope were two sons, Ioannis (1845 – 1916) and Pavlos Damalas (17 July 1853 – 25 December 1925), and a daughter, Eirini (c. 1857 – ?). The family later moved to Marseille, France, where they spent several years until they moved to Ermoupoli, Syros after Ambrosios was appointed mayor there. The family later returned to Marseille and eventually to Piraeus. After finishing school in Piraeus, Damala spent four years abroad, mainly in England and France, where he pursued diplomatic studies. He became acquainted with representatives of high society, as well as the theatre world, since he had the dream of excelling as an actor one day. He returned to Greece in 1878 and recruited in the army. He later trained in the Page Corps in Russia but eventually quit his studies there and returned to Paris.[2] By the early 1880s, he had earned a post as a military attaché to the Greek Diplomatic Corps. He quickly acquired a reputation as "the handsomest man in Europe", as well as the nickname "Diplomat Apollo" by his friends and attribution as the most dangerous man in Paris among husbands who feared their wives would fall victim to his charms and be seduced by the young diplomat.[3] Damala was considered the epitome of handsomeness, and many women of high society in Paris were infatuated with him. He quickly earned the reputation of being a merciless heartbreaker and womaniser of the high circles. Besides his passion for women, he was also said to enjoy the company of young men.[4] His affair with the wife of a Parisian banker, Paul Meisonnier, ruined the woman's reputation to the extent of forcing her to leave France.[5] It was rumoured that he had driven two women to divorce and one to suicide.[6] One of his documented affairs was with the young daughter of a Vaucluse magistrate who had left her parents and home to follow Damala to Paris, where he deserted her when their illegitimate child was born. The young girl was never heard from again; she is presumed to have committed suicide.[7] Following these scandals, Damala was reassigned to Russia. Meeting with Bernhardt and stay in Saint Petersburg Before his transfer, he was introduced to Sarah Bernhardt by her half-sister Jeanne shortly before the summer of 1881. Damala and Jeanne belonged to a circle of well-known morphine-takers who were associated with the stage world. Damala had begun playing small parts as an amateur actor with the stage name of "Daria", and used to frequent the green rooms of theatres, along with fellow actors who shared a similar passion for morphine. He also frequented these places out of his desire to socialise with people from the theatre world and thus promoting his ambitions of becoming a great actor. Jeanne spoke to Bernhardt of Damala, and Bernhardt felt simultaneously repelled and fascinated by the prospect of meeting the most notorious man in Paris. Their meeting was a highly anticipated one from both parties. Madame Pierre Berton, who wrote a biography for Sarah Bernhardt, remarks the following: "It was inevitable that Bernhardt, the famous actress, and Damala, the equally notorious bon-viveur, should eventually meet. Each knew the reputation of the other and their reputation was only the more whetted thereby...Bernhardt prided on her ability to conquer men, to reduce them to the level of slaves; Damala vaunted his ability as a hunter and a spoiler of women...Their two natures were inevitably attracted towards each other...Damala boasted to his friends that, as soon as he looked at her, the great Sarah Bernhardt would be counted in his long list of victims; and Bernhardt was no less certain that she had only to command for Damala to succumb".[8] The two soon met. Although Bernhardt was appalled by Damala's insolence toward her, she was strongly attracted to him and soon fell madly in love with him. During that period, Bernhardt was about to begin her world tour; knowing that Damala was transferred in Saint Petersburg and interested in meeting him again, she decided to arrange a six-month stay in Russia despite the fact she had previously and repeatedly rejected offers of making appearances there. Indeed, she resided in Saint Petersburg for a few months, as an official guest of Emperor Alexander III of Russia, during which her romance with Damala flourished. The openness of their affair scandalised the social circles of the city and proved a common topic of discussion.[9][10] Marriage and new career The match was far from being blissful. Damala developed the habit of openly criticising and mocking Bernhardt in front of her friends. Bernhardt, in return, called him "Gypsy Greek" in an equal attempt to degrade him.[11] However, in most cases, Bernhardt was so overwhelmed by her infatuation for him that she tolerated his insults and even begged him for forgiveness, behaviour which reaffirmed that Damala had the upper hand in the relationship. After Bernhardt left Russia to extend her tour to other European countries, Damala resigned from the Diplomatic Corps and followed Sarah's theatre circle. While in London, completing the final part of her tour, Bernhardt had yet another fight with Damala. Bernhardt was supposed to have created the role of playwright Victorien Sardou Theodora during the tour. Instead, she sent Sardou the telegram: "I am going to die and my greatest regret is not having created your play. Adieu." A few hours later, Sardou received a second message by Bernhardt which simply stated: "I am not dead, I am married".[12] When asked later by Sardou why she had wed, she somewhat naïvely responded that it was the only thing she had never done. Her impulsive decision to marry was probably at her own initiative, as Damala sarcastically admitted to friends that it was she who had proposed to him. The wedding took place on 4 April 1882 in London, a city that proved a convenient choice for marriage, since religious differences would have been a hindrance for a possible marriage in Paris: Bernhardt was a Roman Catholic and Damala Greek Orthodox. Bernhardt's son, Maurice, was hostile to Damala and against this marriage.[13] Even though Bernhardt presented Damala to reporters with the phrase "This ancient Greek god is the man of my dreams",[14] the marriage became the object of criticism and even satire for press. Caricatures of Bernhardt and Damala virtually flooded newspapers for months. A review of Les Mères Ennemies featured Bernhardt holding Damala like a puppet, manipulating his limbs.[15] Damala's marriage to Bernhardt made him even more unfaithful. Three weeks after the wedding, he had a fight with Bernhardt when he insisted she should change her stage name to Sarah Damala to honour him. Following her refusal, he left the house. He was missing for a few days, much to Bernhardt's anxiety, and during this time was seen in the company of a young Norwegian girl. Upon his return, Sarah accepted his excuses. The tour went to Ostend. At their last night there, Damala fled again and was heard from two days later in Brussels, where he was accompanied by a Belgian woman. Bernhardt forgave him again when he returned. Despite the humiliations she endured, giving money to Damala so as to pay his mistresses and debts to prostitutes, and the fact her husband's infidelity had been a common topic for gossip, the lovelorn Benrhardt tolerated all of these. Following their return to Paris, Damala, compelled by the perspective of becoming a theatre star, decided to pursue an acting career. Some time later, Bernhardt bought a theatre, the Théâtre de l'Ambigu, and made the unfortunate decision of appointing Maurice as the manager and Damala as the leading man. Bernhardt's friends could not understand what she saw in him. Her contemporaries were puzzled by her decision to discard professional actors so as to perform next to a rank amateur. Bernhardt seems to have been blinded by emotion: Damala has been described as exceptionally untalented, lacking any acting qualifications, technique, or timing, and possessing an unintelligible Greek accent.[16] Bernhardt was oblivious of all these shortcomings, and on the basis of her attraction for him, considered him appropriate and cast him as Armand Duval in La Dame aux Camélias (The Lady with the Camelias). Bernhardt is cited as telling a (rather shocked) Alexandre Dumas about Damala: "Won't he make an excellent Armand? Only by looking at him, you understand why Marguerite Gautier dies in the way she does!".[14] The couple returned to Paris and performed La Dame aux Camélias. Sarah's performance was exalted; Damala's, on the other hand, received less than enthusiastic reviews. Damala was furious and blamed Bernhardt.[16] SeparationIn December 1882, Bernhardt opened in Victorien Sardou's Fédora and again received excellent reviews. Sardou had written the play specifically for her, but had refused to allow Damala to act in it.[17] Bernhardt appointed her husband manager of her theatrical company on tour ("Head of the Tour"), a decision that proved disastrous, given Damala's lack of skills in managing. Bernhardt was eventually forced to remove him from his post and reduce him to Prince Consort. This development, combined with Damala's frustration over the way his career developed provoked him to continue the habit of humiliating Bernhardt in front of her friends and openly criticising her. His increasingly deeper addiction to drugs, particularly morphine, created even greater problems in their marriage. Damala's drug-influenced behaviour became frequently scandalous. On one occasion, while on stage with Bernhardt, a drug-induced Damala tore down her dress and exposed her bare buttocks to the audience. On 12 December 1882, Bernhardt lashed out against Damala, refusing to cover his expenses on women and drugs anymore, to which Damala responded equally explosively with his own accusations. The next morning Damala left, without notice, for North Africa. Realising he would never be seen as something more than "Mr Sarah Bernhardt", he decided to enlist for service in the spahi troops in Algeria.[18] Bernhardt was left behind to settle for the debts arising from Damala's addiction to drugs and prostitutes as well as her son's gambling. In early 1883, she went to a tour in Scandinavia along with her lover, playwright Jean Richepin. Upon her return to Paris, she found that Damala was again living in her house. Bernhardt left Richepin and the couple reunited for a while; soon, however, the marriage deteriorated even further, due to Damala's extreme drug addiction and the final separation was to come. Allegedly, Bernhardt became so distraught over her husband while performing Ophelia on stage in Italy that she finished her part earlier, came off stage and said: "That's it".[19] Soon after, she moved him out of the house and put him into a clinic. Six months later, he returned to her house again, much to the dismay of Richepin. Bernhardt tried to prevent the pharmacists from providing him with drugs and then put him again to a clinic and later to a hotel, in the outskirts of Paris.[20] However, the two were not divorced and the marriage legally endured until Damala's death in 1889. Since Bernhardt was very strict with her Catholic views, she only opted for a semi-legal separation, which also settled that, in return for certain sums she sent to him on a monthly basis, he would never re-enter her life.[21] Life after separation and health deteriorationFollowing his separation from Bernhardt, Damala attempted returning to the diplomatic world. His re-entrance in the diplomatic profession proved very hard for him, though, and he remained in the acting profession. That same year, in 1883, he performed the most memorable role of his career (save for Armand) as Philippe Berlay opposite Jane Hading in the stage adaptation of Georges Ohnet's novel Maître de Forges (Ironmaster). The play was a great success and ran through the entire year in the Théâtre du Gymnase in Marseille. Damala starred in few memorable productions in the following years. He played the leading man (as Jean Gaussin) in the comedy Sapho, Alphonse Daudet's stage adaptation of his own novel, Sapho, mœurs parisiennes, again with Hading as his partner. The play opened in the Gymnase in Paris on 18 December 1885. Damala also participated in the stage adaptation of another Ohnet novel La Comtesse Sarah, in 1887. Despite these few prolific plays, Damala was quickly forgotten or even deliberately ignored by the Parisian society, following his separation from the great diva. In March 1889, Bernhardt returned to Paris after a year-long European tour and received a message from Damala informing her that he was dying in Marseille and begged her to forgive him and take him back. The fact she never stopped loving and caring for her husband was proved that very moment: she abandoned her performances in Paris, rushed to him and nursed Damala, whose health was wasted as a result of his longtime addiction. She took him in her house and after he recuperated, she cast him as her leading man in La Dame aux Camélias. Damala promised to stop taking morphine and embarked on a European tour with Bernhardt (which also included Egypt). In truth, Damala's addiction to drugs progressively worsened. He continued using the drug and occasionally ridiculed himself, his clarity severely reduced from the morphine. On one occasion, he was almost arrested for exhibiting himself naked in the Hotel de Ville in Milan.[22] Damala reprised his role as Armand but after a six-week run he collapsed and was carried in the hospital. Shortly before his death, he was offered another role by Bernhardt, in the play Lena, at the Théâtre des Variétés. Just after the second performance, he was considered incapable of playing the part, due to his now permanent lack of clarity and continuous influence from alcohol and drugs. Illegitimate daughterIn early 1889, Damala had also fathered a child with one of his mistresses, a theatre extra, who used to inject him with morphine during intermissions. After his mistress gave birth to a baby girl, she placed the baby in a basket on Bernhardt's doorstep with a note. Bernhardt was furious to discover that Damala's illegitimate daughter was placed in her care and contemplated having the infant drowned on the river Seine. Bernhardt's servants attempted to notify Damala of his child, but he was unable to contemplate the situation, due to severely reduced clarity (a result of his deep addiction). Thankfully, his daughter's life was saved by a friend of both Bernhardt and Damala, gun dealer and future tycoon Basil Zaharoff, who proposed to take the child so that he could find a surrogate family for her. Eventually, the girl was baptised Teresa (1889–1967) and was raised in Adrianople in Eastern Thrace, later becoming a socialite in royal Athens society. The adventures of Damala's daughter, who had love affairs with Ernest Hemingway, who called a her a "Greek princess", and Gabriele d'Annunzio, as well getting acquainted with Benito Mussolini, and serving as a model for Pablo Picasso in the early 1920s, were documented by Fredy Germanos in his historical novel Teresa (Greek: Tερέζα, pronounced Tereza), published in 1997. The book also makes reference to Damala's Parisian life and mentions that Bernhardt remained in love with him until the end of her life. In fact, Bernhardt and Teresa Damala met each other again years later. Death Damala was found dead in Paris on 18 August 1889,[23][24] in a hotel room,[24] from an overdose of morphine and cocaine.[25] The news of his death was concealed from Bernhardt until the time she had finished her performance. When she found out, she is cited as saying—presumably out of mercy for his condition—"Well, so much the better...".[26] Bernhardt wore mourning for a year after Damala's death. She had legally adopted his surname (i.e. Sarah Bernhardt-Damala) but never renounced it, even after her husband's death, though this was not widely known. She kept "Damala" as her legal name until she died, though her decision caused her some troubles during World War I when an officer in a consular office at Bordeaux refused to grant her a visa to her passport, due to the fact the latter was Greek (King Constantine of Greece was thought to support the German side during the war and the French state refused to grant visas to Greek passports). It took the intervention of the Minister of Interior for Bernhardt to have her visa granted.[27] LegacyOn one occasion during his marriage to Sarah, the famous author of Dracula, Bram Stoker, dined with Damala backstage at the Lyceum, he noted: "I sat next to him at supper, and the idea that he was dead was strong on me. I think he had taken some mighty dose of opium, for he moved and spoke like a man in a dream. His eyes, staring out of his white, waxen face, seemed hardly the eyes of the living."[28] Later in 1897, Stoker acknowledged that Damala was one of his models for Count Dracula.[29] He has been portrayed by three actors in film and television biopics of Sarah Bernhardt. He was portrayed by John Castle in the film The Incredible Sarah (opposite Glenda Jackson) in 1976, by Canadian actor Jean LeClerc in the TV movie Sarah (also 1976) and by Gonzalo Vega in the Mexican TV series La Divina Sarah (1980). His younger sister, Eirene (c. 1857–?) had a brief affair with notorious Irish-born American author and journalist Frank Harris, as recounted by the latter in his scandalous autobiography My Life and Loves. Harris had met the Damala family in the summer of 1880, when they were all residents at the Hotel d'Athènes, in Athens. Harris and Eirene Damala (referred to in the book as "Mme M.") had a brief romantic/sexual affair, which Harris describes very graphically in his book. Eirene was estranged from her Scottish husband, who had left her and returned to England. Harris also befriended Aristides Damala and the two became even closer friends when they met again in Paris, some time later. Harris also recounts an incident in Trieste when Bernhardt publicly lashed out against her husband for his infidelities, to which Damala responded "Madame, you will never again have the opportunity of calling me names". He then returned to Paris. A disconsolate Bernhardt broke off the tour and also returned to the French capital and begged Harris to intervene for the reconciliation to come. Damala is cited as telling Harris of Bernhardt: "A great talent, but a small nature and a foul tongue".[2] Memorable stage credits

References

|

||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia