|

Invasion of Naples (1806)

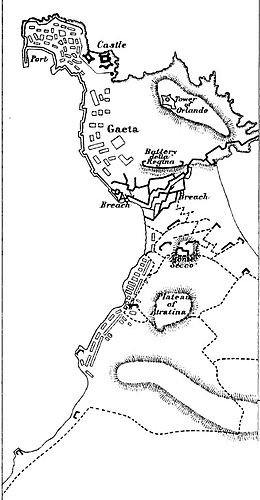

The Invasion of Naples was a front during the War of the Third Coalition, in 1806, when an army of the French Empire led by Marshal André Masséna marched from Northern Italy into the Kingdom of Naples, an ally of the Coalition against France ruled by King Ferdinand IV. The Neapolitan army was defeated at Campo Tenese and rapidly disintegrated. The invasion was eventually successful despite some setbacks, including the prolonged Siege of Gaeta, the British victory at Maida, and a stubborn guerrilla war by the peasantry against the French. Total success eluded the French because Ferdinand withdrew to his domain in Sicily, where he was protected by the Royal Navy and a British Army garrison. In 1806, Emperor Napoleon appointed his brother Joseph Bonaparte to rule over Southern Italy as king. The proximate cause of the invasion was Ferdinand's double-crossing of Napoleon. Wanting to keep things quiet in southern Italy, Napoleon and Ferdinand signed a convention that specified that the French would evacuate Apulia. In return, the Kingdom of Naples would stay neutral in the impending War of the Third Coalition. When the French occupying force marched away, Ferdinand admitted British and Russian armies into his kingdom. In December 1805, Napoleon's armies crushed the armies of Austria and Russia. When the Russian force in Naples was recalled, the British expedition withdrew, exposing Ferdinand's kingdom to French retribution. BackgroundStrategyTo defend his possessions in northern Italy, Emperor Napoleon maintained 94,000 men in the Army of Italy in early 1805. The main army under Marshal André Masséna numbered 68,000 men, the satellite Kingdom of Italy contributed 8,000, and 18,000 watched the border of the Kingdom of Naples under the command of General of Division Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr. However, after accounting for fortress garrisons, military depots, and the sick, only 60,000 troops were available in the field. There were 48,000 in the main army, 2,000 performing internal security functions, and 10,000 under Saint-Cyr.[1] Against these numbers, the Austrian army in Italy under Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen could deploy 90,000 men. Charles decided on a cautious strategy in the autumn campaign because he was anxious about events in Bavaria.[2] Among other things, the Treaty of Amiens of 1802 stipulated that Great Britain must abandon the island of Malta while France had to evacuate the part of the Kingdom of Naples that it occupied. The British politicians soon repented of their actions and refused to give up Malta. Consequently, the French army kept its grip on Apulia in the "heel" of Italy with its strategic ports, Taranto, Bari, and Brindisi.[3] The Neapolitan army of King Ferdinand IV numbered only 22,000 soldiers. Fearful that Saint-Cyr's army might invade his domain, the king agreed with Napoleon to remain neutral during the War of the Third Coalition.[4] The treaty was signed in France on 21 September 1805 by Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord and Ferdinand's minister Gallo. The accord required the Kingdom of Naples to dismiss all foreign officers from its army and not allow foreign troops to land in its territory. In return, the French agreed to evacuate Apulia. The treaty was ratified in Naples on 3 October.[5] Anglo-Russian expeditionsNotified of the terms of the treaty and its ratification, Saint-Cyr immediately evacuated Apulia, and his corps marched north to join Masséna's army in northern Italy. Almost at once, Ferdinand and Queen Maria Carolina reneged on the treaty and treacherously summoned two Coalition expeditionary forces to Naples. Lieutenant General James Henry Craig sailed from Malta with 7,500 British soldiers while General Maurice Lacy of Grodno (1740–1820) led 14,500 Russian troops aboard ship at Corfu.[6] Another authority gave lower numbers, 6,000 in Craig's force and 7,350 in Lacy's corps. The British and Russians landed at Naples on 20 November 1805. By this time, Masséna was in pursuit of Archduke Charles' army. Since Saint-Cyr moved one-third of his command to help besiege the Austrian garrison of Venice, only 10,000 Franco-Italian troops observed the Neapolitan border.[4]  Buoyed by news of the British victory at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805, Craig and Lacy readied their troops for a march into northern Italy. They were dumbfounded to discover that the poorly managed Neapolitan army could not support any offensive move. Without the help of a large body of allied soldiers, Craig and Lacy felt they could only assume a defensive posture. They deployed their troops at the frontier with the British behind the Garigliano River, the Russians on their right in the Apennine Mountains, and a small Neapolitan force under General Roger de Damas on the Adriatic coast in the east. The Neapolitan kingdom called for conscription, but military service was so unpopular that the army's size only increased by 6,000 men. The authorities even used the dubious expedient of pressing jailed convicts into the ranks. In the meantime, a reinforcement of 6,000 Russians landed.[7] Napoleon's great victory at the Battle of Austerlitz on 2 December 1805 brought about the end of the Third Coalition.[8] Czar Alexander soon ordered Lacy to request an armistice and withdraw from Naples. When Craig was informed, he decided that the prudent course was to withdraw the British contingent. These events made the Neapolitan government panic because it knew the kingdom would soon face the French emperor alone.[9] The king understood all too well that he had double-crossed Napoleon.[4] At first, Lacy was willing to interpret his instructions with some latitude. Yet when the Russian general proposed to take up a defensive position in Calabria in the "toe" of Italy, he was rudely rebuffed by the royal court. Insulted, Lacy determined to carry out his czar's orders to leave Naples. Craig first offered to defend the fortress of Gaeta, but its governor, Prince Louis of Hesse-Philippsthal, refused his men's entrance. The British general then suggested that he be allowed to land his troops at Messina. The Neapolitan government rejected this proposal and replied that if he landed his soldiers in Sicily, they would be treated as enemies. Nevertheless, he sailed to Messina after Craig embarked his corps at Castellammare di Stabia on 19 January 1806. There, his men waited on their naval transports until the king and queen came to their senses and allowed them to land on 13 February.[10] ForcesArmy of Naples In January 1806, Saint-Cyr's corps of observation was redesignated the Army of Naples under the nominal command of Joseph Bonaparte, though Masséna was the actual military leader. Napoleon had persuaded his elder brother to accept Naples's crown, and Joseph somewhat reluctantly agreed. Upset with being demoted to second-in-command, Saint-Cyr was recalled early in the campaign. The army was divided into three wings; the right wing and center were concentrated at Rome, and the left wing assembled at Ancona on the Adriatic. General of Division Jean Reynier led 7,500 soldiers of the right wing, Masséna personally commanded the center with 17,500 troops, and General of Division Giuseppe Lechi directed 5,000 men of the left wing. General of Division Guillaume Philibert Duhesme was on the march from Austria with a 7,500-man division, and 3,500 more were due to arrive from northern Italy. Altogether, Masséna's army would number more than 41,000 men.[11] While the Franco-Italian army was in good fighting trim, it suffered from poor administration. The troops were badly paid, fed, shod, and clothed. This led the soldiers to steal from the country's inhabitants, actions that would have consequences.[12]  A month after the invasion in March 1806, the Army of Naples was reorganized into three corps. The I Corps under Masséna consisted of two French infantry divisions under Generals of Division Louis Partouneaux and Gaspard Amédée Gardanne and two French cavalry divisions led by Generals of Division Julien Augustin Joseph Mermet and Jean-Louis-Brigitte Espagne. Partouneaux's division included the 22nd and 29th Line Infantry Regiments in General of Brigade Edme-Aime Lucotte's 1st Brigade and the 52nd and 101st Line in General of Brigade Louis François Lanchantin's 2nd Brigade. All regiments had three battalions. Gardanne's division had three battalions each of the 20th and 62nd Line in General of Brigade Louis Camus' 1st Brigade and one battalion each of the Corsican Legion and the 32nd Light Infantry Regiment plus the three-battalion 102nd Line in General of Brigade François Valentin's 2nd Brigade. Espagne's division was made up of a Polish regiment and the 4th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment in General of Brigade Louis-Pierre Montbrun's 1st Brigade and the 14th and 25th Chasseurs à Cheval in General of Brigade Christophe Antoine Merlin's 2nd Brigade. Mermet's division comprised the 23rd and 24th Dragoon Regiments in the 1st Brigade and the 29th and 30th Dragoons in General of Brigade César Alexandre Debelle's 2nd Brigade. All cavalry units had four squadrons. The corps artillery included six 6-pound cannons, two 3-pound cannons, and five howitzers.[13][14][15] Reynier's II Corps included his own division plus a second division under General of Division Jean-Antoine Verdier. Reynier's all-French division counted the 1st Light and 42nd Line in the 1st Brigade and the 6th Line and 23rd Light in the 2nd Brigade. All regiments had three battalions. Verdier's division comprised the three-battalion 1st Polish Legion and the 1st Battalion of the 4th Swiss in the 1st Brigade and the three-battalion French 10th Line in the 2nd Brigade. Corps artillery had three 6-pound cannons, four 3-pound cannons, and five howitzers.[13] Corps cavalry consisted of the French 6th and 9th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiments with four squadrons each.[16] Duhesme's III Corps comprised Lechi's infantry division and General of Division Jean Henri Dombrowski's cavalry division. Lechi's division was composed of three brigades. Three battalions each of the French 14th Light and 1st Line made up the 1st Brigade, two battalions each of the Italian 2nd and 4th Line Infantry Regiments formed the 2nd Brigade, and two battalions each of the Italian 3rd and 5th Line composed the 3rd Brigade. Dombrowski's cavalry division also counted three brigades. The Italian Napoleone and Reine Dragoons were in the 1st Brigade, the French 7th and 28th Dragoons made up the 2nd Brigade, and the Italian 1st and 2nd Chasseurs formed the 3rd Brigade. Corps artillery deployed six 6-pound cannons and two howitzers.[17] Neapolitan armyThe Neapolitan army was divided into two wings. The left wing under Roger de Damas consisted of 15 battalions and five squadrons, while Marshal Rosenheim's right wing had 13 battalions and 11 squadrons.[11] Damas' infantry contingent included three battalions each of the Princess Royal and Royal Calabrian Regiments, two battalions each of the Royal Ferdinand, Royal Carolina, and Prince Royal Regiments, and one battalion each of the Royal Guard Grenadiers, Royal Abruzzi, and Royal Presidi Regiments. The left wing cavalry counted two squadrons each of the Prince Nr. 2 and Princess Regiments and one squadron of the Val di Mazzana Regiment.[18] The infantry of Marshal Rosenheim's right wing was made up of two battalions each of the Royal Carolina Nr. 2, Albanian, and Royal Sannita Regiments and one battalion each of the Prince Royal Nr. 2, Abruzzi, German, Marie, Sammites, Apulia Chasseurs, and Calabria Chasseurs Regiments.[17] The right wing cavalry comprised three squadrons each of the Val di Mazzana, Royal, and King's Regiments and two independent squadrons. In addition to the two wings, there was the Duke of Hesse's garrison at Gaeta, which included 3,750 regular infantry.[18] Campo Tenese On 8 February 1806, French columns crossed the border, encountering no resistance and throwing the Neapolitan royal court into an uproar.[11] Queen Carolina fled from Naples to Sicily on the 11th. She had been preceded by Ferdinand, who departed on 23 January, even before the invasion.[19] On the Adriatic littoral, Lechi's division seized Foggia after one week. The Italian general eventually turned west, crossed the Apennines, and reached Naples. Masséna's column quickly arrived before Gaeta, about 40 miles (64 km) north of Naples, where Hesse refused to surrender. Since the powerful fortress dominated the coast road, the French commander left Gardanne's division to blockade the place and advanced to Naples with his other infantry division. On 14 February, Masséna seized Naples[20] and Joseph made a triumphant entrance to the city the next day. Ferdinand had left behind large quantities of gunpowder and at least 200 cannons.[21] Reinforced by Verdier's division from Masséna's main body, Reynier's column reached Naples at the end of February after marching on less-traveled roads.[20] Joseph assumed control of the army at this time. He placed all troops in the vicinity of Naples under Masséna, his mobile force under Reynier, and the troops on the Adriatic side under Saint-Cyr. Joseph ordered Reynier to rapidly march to the Strait of Messina.[22] Receiving word that the Neapolitan army was standing to fight to the south, Reynier left Naples and advanced to the attack[20] with approximately 10,000 troops.[22] The Neapolitan armies retired before the French invasion. Rosenheim, whose column was accompanied by Hereditary Prince Francis, retreated in front of Lechi's division on the east coast while Damas watched the French from south of Naples. Damas' left wing had between 6,000 and 7,000 regulars plus Calabrian militia. Rosenheim's right wing counted somewhat fewer soldiers.[22] The commanders of the two Neapolitan wings hoped to unite their forces near Cassano all'Ionio. Damas determined to hold a blocking position in the mountains until his colleague could reach the rendezvous. On 6 March at Lagonegro, Reynier's light infantry advance guard found Damas' militia rear guard under an officer named Sciarpa. The French routed their opponents with a loss of 300 casualties and four artillery pieces.[23] Reynier's scouts detected Damas' position on 8 March, and the French general prepared to attack the following day.[20]  The left wing under Damas numbered about 14,000 soldiers, of whom half were regulars. His force occupied a strong position near Campotenese with his troops behind breastworks.[23] His force was posted in a 1,500 yards (1,372 m) wide valley with both flanks protected by mountains.[20] The entry and exit points to the valley were narrow defiles. The pass behind the Neapolitans was the weak point in the defensive scheme.[23] Damas put nine battalions in the first line, defending three artillery redoubts. The first line was supported by cavalry, and his force balance was deployed in a second line. He did not post any troops to cover the mountains on either flank.[20] Reynier's troops moved out on the morning of 9 March. They were favored by a wind blowing snow in the defenders' eyes.[23] The French general put one brigade in his front line, organized a flanking column to turn the Neapolitan right flank, and posted Verdier in charge of the reserve. It was 3:00 PM before all was ready.[20] Reynier's light infantry negotiated the cliffs on Damas' right flank in a single file and eventually came out behind their adversaries. They spread into a swarm of skirmishers and attacked, sowing confusion. Meanwhile, General of Brigade Louis Fursy Henri Compère led the frontal assault.[24] The main attack first engaged the Neapolitans in a musketry duel, then stormed forward to capture one of the redoubts.[20] The Neapolitan line unraveled, and the men bolted for the exit defile. Soon, the pass was choked by fleeing soldiers, allowing the French to capture about 2,000 of their enemies, including two generals.[24] In the Battle of Campo Tenese, Neapolitan casualties numbered 3,000, while all their artillery and baggage were captured. French losses were unknown but light. This action finished the Neapolitan armies.[25] That evening, Reynier's troops bivouacked at the village of Morano Calabro. A French eyewitness, Paul Louis Courier, wrote of hungry soldiers robbing, plundering, raping, and killing the inhabitants. He later described the war as "one of the most diabolical waged in many years". Reynier covered the 60 miles (97 km) distance to Cosenza by 13 March. A week later, the French were in Reggio Calabria on the Strait of Messina; Prince Francis escaped only a few hours before.[24] While Reynier pursued Damas' wrecked wing, Duhesme and Lechi chased the wing led by Rosenheim and the prince.[26] During this time, the Neapolitan armies disintegrated; only 2,000 or 3,000 regulars from both wings remained to be evacuated to Messina in Sicily. The militia went home while most of the regulars deserted. Before departing for Sicily, Francis urged the militia to form flying columns to resist the invaders.[24] At the time, much of Calabria was a wild place. The 1783 Calabrian earthquakes killed 100,000 people. Parts of Reggio still lay in ruins as late as 1813, and many churches had not been rebuilt in 1806. The hardy Calabrians had a strong independent streak and practiced the vendetta against neighboring families and villages. Plundering French troops and greedy French civil authorities quickly ignited a revolt by the proud Calabrian peasants. However, the people of the major towns hated the Neapolitan royal administration and generally favored the French.[27] The rebellion flared up after individual events. At Scigliano, the French left a detail of 50 soldiers. A woman was raped, the villagers rose up, and most of the Frenchmen were slaughtered. The French commanders had only one answer to such incidents: to attack, plunder, and burn down the offending village. This led to a vicious cycle of atrocity and counter-atrocity.[28] For his part, Joseph Bonaparte tried to be fair, even ordering French soldiers to be shot for criminal offenses and French officials to be tried for malfeasance. Meanwhile, he conferred the title "Prince of Naples" to be hereditary on his children and grandchildren.[29] Maida At this time, the French Army of Naples was reorganized into three army corps (see Army of Naples section). Masséna's I Corps was assigned to besiege Gaeta, Reynier's II Corps ordered to put down the revolt in Calabria, and Duhesme's III Corps sent to occupy Apulia. Meanwhile, King Joseph set about creating a new royal army in Naples. Emperor Napoleon became angry in Paris that many Imperial armies were in front of Gaeta. The emperor impatiently wrote to his brother Joseph, "Gaeta is nothing, Sicily is everything".[26] He understood that Ferdinand's regime could survive intact in Sicily and insisted that 22,000 men quickly invade the island. However, Napoleon failed to give Masséna and Joseph sufficient numbers to accomplish the task. Also, no one seems to have considered how the troops might be ferried across the Strait of Messina.[30] The advance of Reynier's corps to Reggio deeply troubled Craig and Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood. Fearing a French invasion of Sicily, the two procured reinforcements from Malta. Soon after, the sick Craig went home to be succeeded by John Stuart and Collingwood appointed Rear Admiral Sidney Smith to command the local Royal Navy squadron. Stuart and Smith did not like each other, but they agreed to cooperate in the defense of Sicily.[26] However, Smith's stories of his actions at the 1799 Siege of Acre greatly irritated Stuart. Deciding that a raid on Calabria might forestall a French invasion of Sicily, Smith's squadron took 5,200 of Stuart's troops aboard on 30 June 1806. Underestimating Reynier's strength, they intended to drive the French from Calabria with the help of the local partisans.[31] Stuart's force was divided into four brigades under Brigadiers James Kempt, Lowry Cole, Wroth Palmer Acland, and John Oswald. Kempt's Advanced Guard consisted of 535 officers and men in seven light companies, 159 soldiers in the "flanker" battalion of the 5th Foot, and 272 troops in one Sicilian volunteer and two Corsican Ranger companies. Cole's 1st Brigade comprised 781 soldiers in the eight center companies of the 1st/27th Foot, 485 men from six grenadier companies, and 136 artillerists crewing 6-pound cannons. Acland's 2nd Brigade had eight center companies each of the 738-strong 2nd/78th Foot and the 603-man 1st/81st Foot. Oswald's 3rd Brigade included eight center companies each of the 576-strong 1st/58th Foot and the 624-man 20th Foot. Four center companies of De Watteville's Regiment with the strength of 287 soldiers were not attached to any brigade. All told, Stuart commanded 236 officers and 4,960 rank and file.[32]  On 1 July 1806, Stuart's force, including 16 guns, landed in the northern part of the Gulf of Saint Euphemia.[33] The location was designed to split Reynier's forces so that they could be destroyed piece by piece. To confuse the French, the 20th Foot landed farther south in a feint attack.[31] Immediately after landing, the Corsican Rangers headed inland, but they soon bumped into three companies of Polish legionaries who chased them back toward the beach. The 78th Foot and elements of the 1/58th Foot and 1/81st Foot reinforced the Corsicans, and they drove off the Poles. The Advanced Guard marched inland to occupy Nicastro while the rest of Stuart's command camped on the beach.[34] The troops constructed a fortified camp facing south near the village of Sant'Eufemia. To the north was rough terrain dominated by Calabrian partisans, while a coastal plain stretched to the south, the direction from which the French would probably approach.[33] About 200 Calabrian guerillas under a man named Cancellier joined Stuart,[35] but the Britisher did not think they were beneficial.[34]  Leaving garrisons at Reggio and Scilla, Reynier marched north, picking up troops. By 3 July, he assembled 6,440 soldiers near Maida, south of Sant'Eufemia. Verdier's division was somewhere to the north, much too far away to reach the field.[34] When Stuart got news of the French presence, he called in his outposts at Sant'Eufemia and Nicastro. The British general mistakenly believed he outnumbered his adversary.[34] Stuart's seaside camp was supported by Smith's warships anchored inshore. However, some British soldiers were already down with malaria.[35] Leaving 16 officers and 271 men of de Watteville's Swiss Regiment to guard the camp,[32] Stuart marched to the south down the beach. Spotting this maneuver from his hilltop position near Maida, Reynier set his force in motion to attack the British force. He gauged that his advance would strike his enemies at the mouth of the Amato River. Seeing the French approach, Stuart halted his column, faced his troops inland, and moved forward to meet the French. The battleground was in a scrub-covered plain on the north side of the swampy Amato River. Whereas Stuart's force was in the echelon with his right leading, Reynier's division was in the echelon with his left leading. Therefore, the British right and the French left became engaged first.[35] In the Battle of Maida on 4 July 1806, Reynier had three brigades on the field, led by Generals of Brigade Compère, Luigi Gaspare Peyri, and Antoine Digonet. Compère led two battalions each of the 1st Light (1,810) and 42nd Line Infantry Regiments (1,046). Peyri's brigade included two battalions of the 1st Polish Legion (937) and the 1st Battalion of the 4th Swiss Regiment (630). Digonet commanded two battalions of the 23rd Light Infantry Regiment (1,266), four squadrons of the 9th Chasseurs à Cheval (328), and several 6-pound foot and 3-pound horse artillery pieces (112).[32] On the French side, the 1st Light and 42nd Line were on the left, with the 42nd echeloned to the right and rear of the 1st, Peyri in the center, and Digonet on the right. On the British side, Kempt was on the right, Acland was in the center, Cole was on the left with the artillery, and Oswald was in the rear.[34] The British had three cannons while the French had four.[25] As the hostile forces approached each other, Kempt sent the Sicilian volunteers and the Corsican Rangers ahead. Crossing the Amato, they ran into a cloud of French voltigeurs and were driven back. The British brigadier moved the flankers of the 5th Foot and the 20th Foot's light company to check the progress of the enemy skirmishers. Once this was accomplished, the two units reunited with their brigade.[36] Kempt halted his brigade to meet the French charge.[37] There were 700-odd men formed in a two-deep line. The 1st Light advanced with its two battalions in attack columns. At 150 yards (137 m), Kempt's men fired a volley, but the French were not deterred. A second volley fired at a range of 80 yards (73 m) thinned the enemy ranks. Compère was hit, but he still led his soldiers on. At about 20 yards (18 m), Kempt's soldiers fired a final devastating volley. At this, the soldiers of the 1st Light turned and fled, except for a handful who continued to be killed or captured. Compère rode into the British line and was captured. The Advance Guard then charged their fleeing enemies. The British light infantry indulged in an uncontrolled pursuit as far as Maida, taking themselves out of the battle.[36]  Meanwhile, the 42nd Line in attack columns tried to rush Acland's brigade, which began volleying at a distance of 300 yards (274 m). When they saw the 1st Light bolting for the rear, the men of 42nd also ran away.[36] Luckily for Reynier, Kempt's disorderly pursuit gave the Frenchman time to patch up his line.[38] Acland got into a musketry duel with Peyri's brigade, and the Poles soon decamped, but the Swiss battalion refused to panic. The brigades of Acland and Cole converged on Digonet's position, which now included the Swiss. But every time the British advanced, the 9th Chasseurs galloped toward them, forcing them to halt and form a square. The French horsemen would then turn and ride back to the protection of their infantry. Even after Oswald reinforced Acland and Cole, the standoff continued.[39] Fortunately for the British, a breeze was blowing dust and smoke into the faces of the French artillerymen and their aim was poor.[40] Finally, the eight center companies of the 20th Foot appeared on the extreme British left, having returned from their diversionary attack. When the 20th Foot attacked Digonet's right flank, Reynier ordered the remains of his division to retreat to Catanzaro.[39] French losses were 490 killed, 870 wounded, and 722 captured. British losses were far fewer, 45 killed and 282 wounded.[25] His lack of cavalry, the exhaustion of his soldiers, and his innate prudence caused Stuart not to order a pursuit of his beaten enemies.[40] Stuart did his humane best to spare the French wounded from being murdered by the Calabrian partisans, offering a bounty for the recovery of each wounded man. Prevented by the emboldened guerillas from retreating north to Cosenza, Reynier stayed at Catanzaro for the next three weeks with his 4,000 demoralized survivors.[41] Meanwhile, Stuart remained immobile until 6 July while he and Smith decided what to do. They ultimately chose to move south and mop up any French garrisons.[39] Critics later pointed out that with Reynier neutralized, the British had the opportunity to sail either to Naples to depose Joseph or to Gaeta to raise the siege. Instead, they did neither.[42] Other actionsOn 6 July, Stuart captured one-half battalion of Poles at Monteleone di Calabria.[25] The next day, Captain Edward Fellowes of HMS Apollo (38) accepted the surrender of 370 Poles at Tropea Castle. On 9 July, 632 French troops at Reggio capitulated to General Broderick's 1,200 Anglo-Sicilians and Captain William Hoste in HMS Amphion (32).[43] Broderick's force landed south of the town at 7:00 AM. Bombarded from the sea and attacked from the land, the garrison sent out a white flag that evening.[44] Scilla Castle held out until 24 July when its 231-man garrison from the 23rd Light surrendered to Oswald's 2,600 soldiers. Oswald's command consisted of the 10th Foot, 21st Foot, and the Chasseurs Britanniques. On 28 July, Colonel Macleod's 78th Foot and Hoste's Amphion captured 500 men of the 3rd Battalion of the 1st Polish-Italian Legion at Cotrone.[43] Stuart's main body reached Reggio on 23 July. After placing garrisons in Reggio and Scilla, Stuart's troops quit the mainland as Smith's ships transported them to Sicily.[42] Reynier finally began his retreat to the north on 26 July, pursued by 8,000 partisans under Don Nicola Gualtieri, also known as Pane di Grano. The Imperial French troops sacked and burned every village that resisted them along their route. At Strongoli, the guerillas had captured 17 French soldiers and tortured and killed one victim every day. After dropping off its wounded at Cotrone, Reynier's column arrived unexpectedly on 29 July and rescued the ten survivors. Strongoli suffered the same fate as other places that resisted. On 1 August at Corigliano Calabro, Reynier's men fought a pitched battle with the partisans. After routing the Calabrians with heavy losses, the town was burned. Eventually, Reynier reached Cassano, where he joined Verdier, who had seized the town at bayonet point after a bitter struggle.[45] Gaeta In 1806, Gaeta had a population of about 8,000 and possessed powerful fortifications. The city stood on a peninsula that jutted into the sea. Gaeta's landward approaches were defended by a 1,300 yards (1,189 m) long fortified trace three lines deep in places. The Breach Battery was 150 feet (46 m) above the sea, the Queen's Battery even higher, while the Tower of Orlando stood 400 feet (122 m) high. These works could concentrate a large volume of fire against any attacker.[46] Gaeta's garrison under Hesse counted 3,750 foot soldiers disposed in the following regiments: 3rd Battalion of the Presidio (990), 3rd Battalion of the Carolina (850), Prince (600), Val di Mazzara (600), Apulia Chasseurs (110), Val Demone (100), and Val Dinotto (100). There were also 400 volunteers in the garrison. The garrison also included 2,000 irregulars.[18] Many of the regulars were poor material, the scrapings of Neapolitan and Sicilian jails.[47]  Gaeta's commander, Prince Hesse, was an eccentric soldier of fortune. The general was short in stature and red-faced with an aquiline nose. Known for his hard-drinking, he was also a good leader of men. He gained the respect of his poorly motivated soldiers by joking with them and showing outstanding personal courage. From the first days of the siege, he posted himself at the Breach Battery and announced that he would not quit until the siege was done. He also vowed to limit his drinking[47] to only one bottle a day. Referring to Karl Mack von Leiberich's surrender of Ulm, he famously yelled at the besiegers through a speaking-trumpet, "Gaeta is not Ulm! Hesse is not Mack!" When the French arrived in the neighborhood on 13 February, they demanded that the fortress be handed over to them. When Hesse answered the request by firing a cannon, the French left an observation force in the area.[48] The Siege of Gaeta began on 26 February 1806.[43] Masséna reconnoitered the fortress and assigned General of Brigade Nicolas Bernard Guiot de Lacour to command the besiegers. Batteries were dug and armed with cannons from the arsenals at Capua and Naples. The French siege lines were anchored on Monte Secco, 600 yards (549 m) from the fortress and on the more distant Plateau of Atratina. On 21 March, the French formally summoned Gaeta to surrender. Hesse replied that his answer would be found in the breach, which is to say that the French would first have to batter a hole in the wall. But when the besiegers' guns opened fire, they were quickly silenced by the 80 cannons Hesse had trained on their new batteries. The French returned to work rebuilding their batteries, bringing up more cannons, and digging trenches closer to the defenses. On 5 April, Hesse refused another French summons. When the besiegers' cannons opened fire, they were again rapidly put out of action by the superior weight of Gaeta's artillery.[49] Realizing that Gaeta could not be cheaply taken, the French appointed General of Brigade Jacques David Martin de Campredon, an engineering expert, to direct the siege. To get close enough to blast a breach in the walls, the French began digging parallels into the ground in front of Monte Sacco. Because the soil was rocky, this process was complex.[49] Hesse was reluctant to mount sorties to destroy the French siege lines because the Neapolitan soldiers would frequently desert to the French. Hesse requested assistance from his government but did not receive any right away because Admiral Smith was fully employed in supporting the guerrilla war in Calabria.[50] At length, Smith's squadron arrived at Gaeta and dropped off food, four heavy cannons, and the partisan leader Michele Pezza, also known as Fra Diavolo. Smith also ordered some gunboats under Captain Richardson to stand by the fortress, a reinforcement which proved troublesome to the enemy.[50] Sometime in April, the Royal Navy landed Fra Diavolo and a considerable force of irregulars near the mouth of the Garigliano. Their raid was successful initially, but the partisans were finally scattered, and Fra Diavolo returned to Gaeta. When Fra Diavolo was later implicated in a scheme to betray Gaeta, Hesse shipped him back to Palermo in chains.[51]  Until the end of May, the French besiegers never had more than 4,000 men. But after that date, they started to get heavily reinforced, so their numbers doubled by 28 June. On that day, Masséna took personal command of the siege. In the meantime, the garrison made sorties on 13 and 15 May, putting a few cannons out of action and carrying off some prisoners. By early June, the French had dug parallels within 200 yards (183 m) of the fortress and constructed batteries for 100 cannons. All the work was done under murderous defensive fire from Gaeta.[52] French General of Brigade Joseph Sécret Pascal-Vallongue was mortally wounded in the head on 12 June and died on the 17th.[53] On 28 June, the French opened fire with 50 heavy cannons and 23 mortars. Gaeta's artillery could not suppress the besiegers' fire this time, which dismounted some guns and caused numerous casualties. By 1 July, the bombardment had blown up three powder magazines in the fortress, but Hesse refused to give up. There was a lull while the French sapped closer to the walls.[54] On the 3rd, 1,500 reinforcements to the garrison arrived by sea. That evening, Richardson's vessels bombarded the French lines without result. At 3:00 AM on 7 July, the French opened fire again with 90 cannons. The mutual bombardment inflicted great damage to both attackers and defenders. But the greatest loss to the defenders occurred when Hesse was badly wounded by a bursting shell on 10 July and had to be evacuated by sea. His replacement was Colonel Hotz, an officer of only ordinary talent. Worried that their supply of shells would run out, the French offered a bounty for the recovery of unexploded ordnance. On the 11th, Masséna's artillery commander, General of Brigade François Louis Dedon-Duclos, begged the marshal to pause the bombardment, lest they run out of ammunition. Hoping that the loss of Hesse would demoralize Gaeta's garrison, Masséna ordered the fire to continue.[55] On 12 July 1806, two breaches began to be seen in Gaeta's walls, one at the Breach Battery on the left and one under the Queen's Battery on the right. Surrender was demanded, but Hotz refused. The bombardment continued, and on the 15th, a French engineer officer crept far enough forward to note that the west breach could be attacked. By 16 July, Masséna had heard about the French defeat at Maida and was anxious to capture Gaeta. There remained only 184,000 pounds of gunpowder and less than 5000 shot, a three-day supply.[55] By this time, the French had 12,000 troops in Partouneaux and Gardanne's infantry divisions, with Espagne and Mermet's cavalry divisions in support.[43] Despite the ammunition shortage, the bombardment dragged on, widening the breaches. Normally, the commander of the besiegers kept the time of the final assault on a fortress a secret from the defenders. But Masséna intended to overawe Hotz with his deliberate preparations for an attack. On the morning of 18 July, in full view of the defenders, the French massed a force of grenadiers and chasseurs under General of Brigade François-Xavier Donzelot to attack the left breach, while voltigeurs led by Valentin assembled to assault the right breach. The French ostentatiously marched up supporting troops. Masséna's gamble had the intended effect when Hotz put up a white flag at 3:00 PM.[56] Because of its prolonged defense and because he needed to capture Gaeta quickly, Masséna granted lenient terms to Hotz. The garrison was allowed to sail away to Sicily on the promise not to fight against France for one year. The fortress and all its cannons, one in three damaged, were given over to French control. An embarrassing incident occurred when a considerable body of the Neapolitan regulars deserted to the French. The French admitted losses of 1,000 killed and wounded, but they may have been twice that.[57] Out of a garrison of 7,000, the Neapolitans lost 1,000 killed and wounded plus 171 cannons.[43] Notes

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia