|

In the Bleak Midwinter

"In the Bleak Midwinter" is a poem by the English poet Christina Rossetti. It was published under the title "A Christmas Carol" in the January 1872 issue of Scribner's Monthly,[1][2] and first collected in book form in Goblin Market, The Prince's Progress and Other Poems (Macmillan, 1875). It has been set to music several times. Two settings, those by Gustav Holst and by Harold Darke, are popular and often sung as Christmas carols. Holst's is a hymn tune called Cranham, published in 1906 in The English Hymnal and simple enough to be sung by a congregation.[3] Darke's is an anthem composed in 1909 and intended for a trained choir; it was named the best Christmas carol in a 2008 poll of leading choirmasters and choral experts.[4] AnalysisA Christmas Carol

Christina Rossetti, (1872)

In verse one, Rossetti describes the physical circumstances of the Nativity of Jesus in Bethlehem. In verse two, Rossetti contrasts Christ's first and second coming. The third verse dwells on Christ's birth and describes the simple surroundings, in a humble stable and watched by beasts of burden. Rossetti achieves another contrast in the fourth verse, this time between the incorporeal angels attendant at Christ's birth with Mary's ability to render Jesus physical affection. The final verse shifts the description to a more introspective thought process. Literary critics have questioned a number of aspects of Rossetti's poem. Professor of Historical Theology, John Mulder, with his coauthor and fellow Presbyterian minister, F. Morgan Roberts, have noted that the reference to winter weather in the title and first verse is incongruous with its geographical setting in the hot climate of Judea. They note that, "Although not unheard of, snow in Palestine is rare", and that Rossetti was writing at a time when popular literary works such as Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol (1843) had established the strong association of snow with Christmas in the English mind.[5] Musicologist C. Michael Hawn, however, asserts that Rossetti is not implying that snow literally fell in Palestine, but that the wintry conditions described are a metaphor for a "harsh spiritual landscape" experienced at the time of Christ's birth, referring to the political oppression of Jews during the Roman occupation of Palestine.[6] Hymnologist and theologian Ian Bradley has questioned the poem's theology: "Is it right to say that heaven cannot hold God, nor the earth sustain, and what about heaven and earth fleeing away when he comes to reign?", which he considers not justified by scripture. He concedes that the image of a heaven unable to contain God, could be read as a "bold and original attempt to express the mysterious paradox at the heart of the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation".[7][8] Several writers have conversely pointed to scriptural precedent for the lines that Bradley finds questionable.[9][10] Mulder and Roberts have commented that Rossetti's lines "Heaven and earth shall flee away, When He comes to reign" accord with the apocalyptic account of the second coming in Revelation 21:1:[a] "Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away."[5] Guidance on the hymn, provided by the Methodist Church UK for their churches, notes that Solomon asks a similarly-phrased question in 1 Kings 8:27:[b] "But will God really dwell on earth? The heavens, even the highest heaven, cannot contain you ..." when he dedicates the temple. It also points to 2 Peter 3:10–11[c] as New Testament support for the phrase "heaven and earth shall flee away":[11]

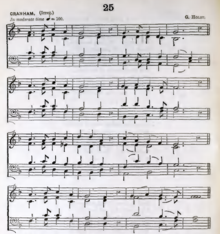

SettingsThe text of this Christmas poem has been set to music many times. Two of the most famous settings were composed by Gustav Holst and Harold Darke in the early 20th century. Holst Holst's setting, Cranham, is a hymn tune setting suitable for congregational singing, since the poem is irregular in metre and any setting of it requires a skilful and adaptable tune.[9] The hymn is titled after Cranham, Gloucestershire and was written for the English Hymnal of 1906.[12][3]  DarkeThe Darke setting was written in 1909 while he was a student at the Royal College of Music. Although melodically similar, it is more advanced; each verse is treated slightly differently, with solos for soprano and tenor (or a group of sopranos and tenors) and a delicate organ accompaniment.[7] This version is favoured by cathedral choirs and is the one usually heard performed on the radio broadcasts of Nine Lessons and Carols by the King's College Choir. Darke served as conductor of the choir during World War II.[13]  Darke omits verse four of Rossetti's original, and bowdlerizes Rossetti's "a breastful of milk" to "a heart full of mirth",[14] although later editions reversed this change. Darke also repeats the last line of the final verse. Darke would complain, however, that the popularity of this tune prevented people from performing his other compositions, and rarely performed it outside of Christmas services.[15] In 2016, the Darke setting was used in a multitrack rearrangement of the song by music producer Jacob Collier. It features contemporary compositional techniques such as microtonality.[16] Other settings Benjamin Britten includes an elaborate five-part setting of the first verse for high voices (combined with the medieval Corpus Christi Carol) in his work A Boy was Born. Other settings include those by Robert C. L. Watson, Bruce Montgomery, Bob Chilcott, Michael John Trotta,[17] Robert Walker,[18] Eric Thiman, who wrote a setting for solo voice and piano, and Leonard Lehrman.[19] See alsoNotesBiblical verses citedReferences

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to In the Bleak Midwinter. Wikisource has original text related to this article:

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia