|

Imperial Guard Cavalry (First Empire)

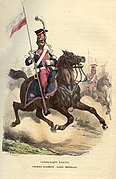

The Imperial Guard cavalry corresponds to all the military cavalry units belonging to Napoleon I's Imperial Guard. An elite fighting unit, it became the army's ultimate reserve. It was used as a last resort to deliver the coup de grâce or break the deadlock in perilous situations. In 1804, the Imperial Guard cavalry initially comprised three units: mounted grenadiers, mounted chasseurs, and mamelukes. Subsequently, other cavalry corps joined the Imperial Guard, such as the dragoons in 1806, the Polish lancers in 1807, the red lancers in 1810, the Lithuanian lancers and Lithuanian tatars in 1812, and the scouts in 1813. Other cavalry units were attached to the Imperial Guard or served alongside it, such as the elite gendarmes, the gendarmes d'ordonnance, the chevau-légers de Berg, and the guards of honour. At the height of the First Empire in 1812, the Imperial Guard numbered around 7,000 cavalrymen, while the Grande Armée as a whole numbered approximately 77,000. From its creation until 1813, the Guard cavalry was commanded by Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessières, Duke of Istria. Killed by a cannonball at the start of the German campaign, his command was taken over by General Nansouty. Organic UnitsThe Imperial Guard was created at the start of the First Empire by imperial decree on July 29, 1804, replacing the Consular Guard. It initially comprised three cavalry units: the régiment des mounted chasseurs, the mounted grenadier regiment, and the mameluk company (attached to the mounted chasseurs). The elite gendarmes were also part of the Imperial Guard, but their roles and missions differed from those of the other units. In 1806, the Dragoons regiment was created. The Polish lancers regiment was formed in 1807, and recruited from the Polish nobility. The lance was not introduced until 1809, after the Battle of Wagram. In 1810, a new regiment of lancers, the red lancers, was formed from the regiment of hussars of the Dutch Guard. In 1812, a third regiment of lancers, the Lithuanian lancers, was recruited, along with a squadron of Lithuanian tatars. In 1813, three regiments of lance-armed scouts were formed. The first was attached to the mounted grenadiers, the second to the dragoons, and the third to the Polish lancers. The mounted grenadiers, mounted chasseurs, mamelukes, dragoons, Polish lancers, and the 1st squadron of the 1st scout regiment formed part of the prestigious Old Guard. Mounted grenadiersThe origins of the mounted grenadiers date back to October 1796, when the French government decided to incorporate a mounted unit into the Directoire Guard: a corps of two companies, totaling 112 cavalrymen, was created.[1] The following year, this unit was renamed the mounted grenadiers, and after the coup d'état of 18 Brumaire, it became the first cavalry formation of the Consular Guard.[1]  In 1804, with the establishment of the First Empire, the corps of mounted grenadiers of the Consuls' Guard became the regiment of mounted grenadiers of the Imperial Guard, comprising four squadrons with a total strength of 1,018 cavalrymen.[2] They took part in the Austrian campaign of 1805 and particularly distinguished themselves at Austerlitz, where their charges against the cavalry of the Russian Guard, in the company of chasseurs and mamelukes, proved effective in repelling Grand Duke Konstantine's counter-attack.[3] Absent from the Prussian campaign, they made up for lost time at the Battle of Eylau, when Colonel Lepic and his grenadiers managed to break through the encirclement to the French lines.[4] The regiment then left for Spain but was not much used there. In 1809, the mounted grenadiers were present at Essling and Wagram. Their strength was increased to five squadrons in 1812, on the eve of the Russian campaign.[2][5] During the latter, they suffered heavy losses, and the regiment was reduced to four squadrons in February 1813.[2] It subsequently fought in the German campaign and the French campaign, notably at Vauchamps and Craonne. Under the First Restoration, the mounted grenadiers were renamed the Corps Royal des Cuirassiers de France. During the Hundred Days, the regiment reverted to its former name and took part in the Belgian campaign of 1815, charging the British squares at the Battle of Waterloo. The Mounted Grenadiers Corps was finally disbanded on November 25, 1815, during the Second Restoration.[2] Mounted chasseursOn April 24, 1796, during the first Italian campaign, General Napoleon Bonaparte ordered the creation of a company of mounted guides to protect him and his staff. Captain Bessières, of the 22nd Regiment of Mounted Chasseurs, took command of the corps, with the power to appoint or dismiss soldiers for his unit.[6] The compagnie des guides distinguished itself at Arcole, before taking part in the Egyptian campaign, where it charged at Mont-Tabor and Saint-Jean-d'Acre. After Napoleon's return to France and the establishment of the Consulate, the compagnie des guides became the company of mounted chasseurs of the Consular Guard, with Captain Eugène de Beauharnais as its commander.[7]  In 1804, Napoleon became Emperor and established the Imperial Guard. The compagnie des chasseurs became the régiment des chasseurs à cheval de la Garde impériale, organized into four squadrons totaling 1,018 men, to which was added the compagnie des mameluks.[8] The unit took part in the Austrian campaign of 1805, under the command of Colonel Morland: at Austerlitz, they repelled the Russian Guard cavalry, together with mounted grenadiers and mamelukes, for 22 killed, including Morland.[9] The regiment did not take an active part in the Prussian campaign of 1806, but the following year charged the Russian infantry at Eylau under the command of General Dahlmann, who was mortally wounded. In 1808, General Lefebvre-Desnouettes took command of the Guard's mounted chasseurs. That same year, they took part in the Spanish War, helping to suppress the Dos de Mayo uprising.[10] Defeated at Benavente, the chasseurs moved on to central Europe and distinguished themselves at the Battle of Wagram, where they routed Austrian cavalry in the company of Polish chevau-légers.[11] In 1812, during the Russian campaign, the Guard mounted chasseurs to protect Napoleon at the battle of Gorodnia, repelling the Cossacks with the help of the other Guard cavalry regiments.[12] By the end of the campaign, the unit had been reduced to 209 cavalrymen, but their numbers were increased and they took part in the campaigns in Germany and France, notably at Leipzig, Hanau, Montmirail and Craonne. During the First Restoration, the Guard's mounted chasseurs became the Corps royal des chasseurs de France, before reverting to their former name during the Hundred Days, when they charged at Waterloo.[13] The Imperial Guard mounted chasseurs unit was disbanded between October 26 and November 6, 1815, during the Second Restoration. MameluksIn 1798, during the Egyptian campaign, General Napoleon Bonaparte confronted the Mameluks, cavalrymen who had been subjugated to the Ottoman Empire for several centuries. Impressed by their qualities as soldiers, he decided to incorporate a similar unit into the French army.[14] These mamelukes followed the expeditionary corps on its return to France, and on October 13, 1801, a decree ordered the creation of a 240-strong mameluke squadron as part of the Consular Guard, a number later reduced to 150 on January 7, 1802.[15] The squadron was commanded by Colonel Jean Rapp, Napoleon's aide-de-camp. On April 21, 1802, the squadron had 13 officers and 155 men.[16] In 1804, the Mamluks were reduced to a single company, attached to the mounted chasseurs of the Imperial Guard.[17]  Taking part in the Austrian campaign of 1805, the Mamelukes particularly distinguished themselves at Austerlitz: while the French infantry was being battered on the Pratzen plateau by the cavalry of the Russian Guard, the Emperor ordered Marshal Bessières to charge with the cavalry of the Imperial Guard, held in reserve. An initial attack by the chasseurs and grenadiers having failed, the mamelukes in turn attacked, breaking through a Russian square and capturing a battery.[18] After this engagement, Napoleon awarded the company an eagle. The Mamelukes then took part in the Prussian and Polish campaigns, where they were present at the Battle of Eylau. During the Spanish Civil War, they played an active role in suppressing the Dos de Mayo uprising, earning the hatred of the Spanish who saw them as descendants of the Moors.[19] In 1812, the company was involved in the Russian campaign, following in the footsteps of the chasseurs, and suffered heavy losses. Reorganized as a squadron in 1813, the Mamelukes fought in the German campaign at Dresden and Hanau, and in the French campaign at Montmirail, Saint-Dizier, and Paris. Under the First Restoration, the squadron was incorporated into the Corps Royal des Chasseurs de France, then reformed by decree during the Hundred Days. After Napoleon's second abdication, the last Mamelukes returned to the refugee depot in Marseille, where they were almost all massacred by the royalist population.[20] DragoonsThe creation of the régiment des dragons de la Garde impériale dates back to April 1806: satisfied with the participation of the dragoons de la ligne in the Austrian campaign of 1805, Napoleon decreed the formation of a dragoon regiment integrated into the Imperial Guard.[21] The unit was organized into four squadrons, each with two companies, and the Emperor personally appointed the corps officers from the Guard or the line.[22] The regiment was placed under the command of Colonel Arrighi de Casanova.[23]  A few months later, they were present at the Battle of Friedland, where they formed the left flank of the Guard cavalry formation.[24] During the Russian campaign, notably at Maloyaroslavets and Berezina, the regiment was almost entirely decimated while covering French troops during the retreat from Russia.[25] In 1813, the dragoons took part in the battles of Leipzig and Hanau. At the Second Battle of Saint-Dizier in 1814, accompanied by a platoon of Mamelukes, they dislodged enemy soldiers from their positions and captured 18 pieces of artillery.[26] During the First Restoration, the regiment was transformed into the Corps Royal des Dragons de France. On Napoleon's return during the Hundred Days, the regiment returned to its previous organization. On June 18, 1815, under the command of Marshal Ney, they set off against the British squares positioned on Mont-Saint-Jean, where they suffered heavy losses in the face of precise British infantry fire. By the end of the Belgian campaign, the regiment had lost 25 officers and almost 300 soldiers. The regiment was finally disbanded after Napoleon's second abdication.[25] Polish lancersIn 1807, after defeating Prussia, Napoleon entered Warsaw, escorted by a dashing Polish honor guard of noblemen. Seduced, on April 6 the Emperor decreed the creation of a regiment of Polish chevau-légers integrated into the Imperial Guard and placed under the command of colonel Krasiński.[27][28] Comprising 968 men with no military experience, the unit was supervised by Guards cavalry officers, such as the two colonel-majors.[29]  As they formed up, the Polish detachments headed for the Chantilly depot, then on to Spain, where they were to fight.[29] They were present at Medina de Rioseco, then at Burgos under the command of General Lasalle.[30] As Napoleon marched on Madrid, he was blocked on November 30, 1808, at the Somosierra Pass by the troops of General Benito de San Juan.[31] With the infantry unable to take the position, the Emperor ordered the 3rd squadron of Polish chevau-légers to charge. Commanded by Kozietulski, the Poles suffered heavy losses from Spanish infantry and artillery fire but managed to capture the opposing batteries.[32] Their decisive intervention was hailed by Napoleon, who gave the regiment the rank of Old Guard. Back in France, the chevau-légers took part in the Austrian campaign of 1809, particularly at Wagram, where they overpowered Schwarzenberg's uhlans.[33] After this confrontation, the Emperor agreed to Colonel Krasiński's request to equip his men with lances, and the unit took the name of "Polish Lancers". In 1810, the Lancers regiment took the number 1 after the creation of the Red Lancers.[34] It was then engaged in the Russian campaign, where it distinguished itself at Gorodnia and Krasnoi. After heavy losses, the Polish lancers were reorganized and took part in the battles of the German campaign in 1813, as at Lützen, Peterswalde, and Hanau, where they lost Major Radziwill.[35] In 1814, during the French campaign, they charged at Brienne, La Rothière, Montmirail, Berry-au-Bac, Craonne, Reims, and Paris. During the First Restoration, the Polish Lancers were disbanded and sent back to Poland, except for a squadron commanded by Jerzmanowski, which accompanied Napoleon to Elba.[36] During the Hundred Days, this squadron became the 1st of the Red Lancers regiment, with which it charged at Waterloo. At the time of the Second Restoration, the Polish squadron was definitively disbanded and its members enlisted in the Russian army.[37] Red LancersIn 1810, Napoleon annexed the Kingdom of Holland and forced his brother Louis to abdicate. On July 14, a decree officially announced the attachment of Holland to the Empire, and at the same time prescribed the incorporation of the Dutch Royal Guard into the Imperial Guard.[38] On August 10, the Royal Guard hussar regiment, under the command of Colonel Dubois, left the kingdom for Versailles, arriving on August 30. Organized into four squadrons, the Dutch fraternized with their French comrades. A decree of September 13, 1810, transformed the hussars into a second regiment of Imperial Guard lancers.[39] General Colbert-Chabanais took command, and non-commissioned officers from the corps, instructed by Polish lancers from the 1st regiment at Chantilly, taught their men how to handle the lance.[40]  In 1812, the regiment was involved in the Russian campaign. Placed in the vanguard, the red lancers seized numerous convoys of goods and provisions, then formed a brigade with the Polish lancers, under the command of general Colbert-Chabanais.[41] Arriving in Moscow in September, their battle strength rose to 556 cavalrymen by October.[42] After the burning of Moscow and the battle of Winkowo, Colbert's lancers were placed in the rear to cover the retreat. On October 24, they repelled a large party of Cossacks, outnumbered, who attempted to attack the rearguard.[43] Because of the weather conditions, losses in men and horses were heavy, and by the end of the campaign, only 60 lancers still had a mount.[44] Reorganized, the 2nd Lancers then took part in the German campaign, where they distinguished themselves at the battle of Reichenbach on May 22, 1813. In 1814, the red lancers of the Jeune Garde fought in Belgium, while the squadrons of the Moyenne Garde confronted the coalition armies in numerous clashes during the French campaign. The First Restoration transformed the 2nd Lancers into the Corps royal des chevau-légers lanciers de France. During the Hundred Days, the regiment reverted to its former name, taking in the squadron of Polish lancers from the island of Elba.[45] It joined the light cavalry division of the Guard with mounted chasseurs, and took part in the Belgian campaign of 1815. The Red Lancers were present at Quatre Bras and charged the British squares at the Battle of Waterloo.[46] After Napoleon's second abdication and the return of the Bourbons, the regiment was disbanded on August 30, 1815. Lithuanian lancersAt the beginning of July 1812, Napoleon decided to form a 3rd Lancers regiment as part of the Imperial Guard,[47] with a theoretical strength of 1,218 men divided into five squadrons.[48] Two squadrons were formed in Warsaw with Lithuanian noblemen.[49][50] Command of the regiment was entrusted to General Konopka, Major of the Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard.[51] A squadron of Lithuanian Tarars was attached to the corps to carry out reconnaissance missions.[52]  Having received orders to go to Minsk, the 3rd Lancers set off as part of the Russian campaign. On the way, Konopka decided to stop in the village of Slonim, where he set up camp.[53] Colonel-major Tanski, who advised his commander to leave as soon as possible, was sent back to the depot in Grodno, but the night after his departure, Russian general Czaplicz attacked the Lancers' camp with his soldiers; General Konopka and 246 men were taken prisoner.[54] The regiment also lost important equipment, as well as the corps' registers, papers, and accounts.[49] After this defeat, Major Tanski's other two squadrons in Grodno formed the 3rd Lancers, but the unit was finally disbanded on March 22, 1813, and its elements were incorporated into the Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard.[49] Lithuanian tatarsThe idea of creating a unit of Lithuanian Tartars was born in June 1812. The latter, members of communities originally from the Crimea, had the reputation of being excellent horsemen, as confirmed by General Michel Sokolnicki, who stated that "their probity, as well as their courage, are tried and tested".[55] Napoleon called on Major Mustapha Achmatowicz to recruit a thousand soldiers, but only one squadron was set up.[52] The unit was officially created in October 1812, and attached to the 3rd Lancers of the Imperial Guard.[56][57]  Commanded by Achmatowicz, the Tartars took part in the Russian campaign, following in the footsteps of the lancers.[52] They suffered heavy losses defending Vilna against the Russians, including Achmatowicz, who was killed.[58] At the end of the campaign, the survivors were incorporated into the ranks of the 3rd Guards Lancers, then formed the 15th company of the Polish Lancers regiment of the Imperial Guards.[59] Despite their small numbers, the Tatars were able to maintain their position in the ranks of the Imperial Guards. Despite their small numbers, the Lithuanian Tartars of Captain Ulan, who had replaced Achmatowicz, charged repeatedly during the German campaign and again distinguished themselves in France as part of the 3rd regiment of scouts-lanciers.[60][61] After Napoleon's abdication on April 6, 1814, the last Lithuanian Tartars returned home.[60] Mounted chasseurs of the Young GuardOn March 6, 1813, the Imperial Guard mounted chasseur regiment grew from five to nine squadrons. The 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th squadrons took the title of "second chasseurs", then "Jeune Garde mounted chasseurs".[62] At this time, the corps was commanded by Colonel Major Charles-Claude Meuziau, with whom it took part in the German campaign of 1813. In 1814, the chasseurs were detached to General Maison's Armée du Nord, where they were mainly tasked with reconnaissance missions, although this did not prevent them from charging on several occasions, as at Courtrai on March 30.[63] The squadrons were disbanded during the First Restoration, most of the men being returned to the line or placed on half-pay. During the Hundred Days, the Jeune Garde squadrons were reformed and renamed the Second Imperial Guard mounted chasseur regiment. However, due to a shortage of men and horses, the unit did not leave its Chantilly garrison and did not take part in the Belgian campaign of 1815. The régiment des chasseurs de la Jeune was finally disbanded between October 8 and November 8, 1815.[64] ScoutsGiven the dramatic prospect of having to fight on French soil for the first time since the wars of the Revolution, Napoleon reorganized his Imperial Guard on December 4, 1813. Three regiments were created: the first, comprising the scout-grenadiers, was attached to the mounted grenadiers; the second, comprising the scout-dragoons, was attached to the dragoons; and the third, comprising the scout-lancers, was attached to the Polish lancers. These new units had time to take part in the French campaign of 1814, where they clashed repeatedly with the Cossacks. Although tasked with reconnaissance missions at outposts, they also led charges on several occasions, such as at Brienne, Montmirail, and Craonne, when Colonel Testot-Ferry led the 1st regiment in an assault on Russian artillery. They also took part in the defense of Paris, before being disbanded during the First Restoration. Units attached to the Guard or operating in conjunction with itElite gendarmesThe elite gendarmerie was created in July 1801 and integrated into the Consular Guard in July 1802, in the form of a squadron.[65] Integrated into the Imperial Guard in 1804, the elite gendarmerie comprised two squadrons each divided into two companies, plus two short-lived companies of foot gendarmes.[66] A minimum height of 1.76 meters is required for recruitment.[67] At its creation, the unit comprised 632 officers, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers, including foot gendarmes. The elite gendarmes were part of the prestigious Old Guard. In 1806, the companies of foot gendarmes were disbanded, reducing the number of cavalry to 456.[66]  The elite gendarmerie was responsible for the security of the imperial palaces and military quarters and protected Napoleon's campaign headquarters.[68] It was also used, albeit less frequently, to escort the Emperor on his travels and to protect important figures.[66] Although they played a relatively minor role in the wars of the First Empire, the elite gendarmes charged at Medina de Rioseco and Montmirail, and took part in the Belgian campaign of 1815. The elite gendarmes unit was finally disbanded in September of the same year. Gendarmes d'ordonnanceBy decree of October 1st, 1806, Napoleon ordered the creation of a Regiment de Gendarmes d'Ordonnance, attached to the Imperial Guard.[69] The Emperor hoped to reconnect with members of the Ancien Régime aristocracy, who had been banished during the French Revolution. In theory, anyone could join this new unit, but recruits had to spend 1,900 francs on uniforms and equipment.[70] He also had to prove that his family was paying him a pension of 600 francs.[69] On August 1st, 1807, the gendarmerie d'ordonnance numbered 216 cavaliers.[71] Berg chevau-légers

Honor guards

The Guards of Honor are four light cavalry regiments raised in 1813 by Napoleon to reinforce the Imperial Guard cavalry decimated during the Russian campaign of 1812. Dressed à la hussarde, drawn from the bourgeoisie and petty nobility and equipping themselves at their own expense, they were attached to the Guard on July 29, 1813: "the 1st regiment was attached to the mounted chasseurs, the 2nd to the dragoons, the 3rd to the grenadiers and the 4th to the lancers".[73] Command From 1804 to 1813, Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessières, Duke of Istria, was commander-in-chief of the Imperial Guard cavalry. A former captain in the 22nd mounted chasseur regiment, in 1796 he took charge of the company of guides, with whom he took part in the campaigns of Italy and Egypt.[74][75] He charged at the Battle of Marengo with the cavalry of the Consular Guard, and was promoted to brigadier general in July 1800. When the First Empire was established in 1804, he was elevated to the dignity of maréchal d'Empire and appointed colonel-general of the Imperial Guard cavalry.[76] Bessières set about reforming the corps, imposing strict discipline. He commanded the Guard cavalry during parades, as well as during military campaigns.[77] During battles, Bessières, "a reserve officer full of vigor, but prudent and circumspect" according to Napoleon, personally led the charges of his cavalrymen in the face of the enemy.[78] The marshal was much appreciated by his men, and when he was wounded by a cannonball at Wagram, the Emperor told him: "Bessières, here's a fine cannonball, it made my Guard cry".[78] He remained commander-in-chief of the Guard cavalry during the Russian campaign of 1812, before taking part in the German campaign the following year.[79] On May 1st, 1813, near Weißenfels, he was killed by an Austrian cannonball that cut off his hand and pierced his chest. His death was deeply resented by the army and by Napoleon.[80] On July 29, 1813, General Étienne Marie Antoine Champion de Nansouty succeeded Bessières as commander-in-chief of the Guard cavalry.[81] Considered one of the best cavalry generals in the army, Nansouty led the Guard cavalry during the German campaign, particularly at the battle of Hanau, where he brought down the Bavarian infantry and cavalry with a series of vigorous charges. He again played a decisive role in the victories of Montmirail and Château-Thierry in 1814, but his relations with the Emperor deteriorated and he left his command, officially for health reasons, on March 8, shortly after the battle of Craonne. General Augustin-Daniel Belliard took interim command of the Guard cavalry at the battle of Laon before General Horace Sébastiani took permanent command until the end of the 83rd campaign.[82]

Gallery

See alsoReferences

Further reading

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia