|

History of trigonometry

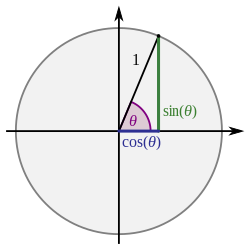

Early study of triangles can be traced to the 2nd millennium BC, in Egyptian mathematics (Rhind Mathematical Papyrus) and Babylonian mathematics. Trigonometry was also prevalent in Kushite mathematics.[1] Systematic study of trigonometric functions began in Hellenistic mathematics, reaching India as part of Hellenistic astronomy.[2] In Indian astronomy, the study of trigonometric functions flourished in the Gupta period, especially due to Aryabhata (sixth century AD), who discovered the sine function, cosine function, and versine function. When during the Middle Ages, the study of trigonometry continued in Islamic mathematics, by mathematicians such as Al-Khwarizmi and Abu al-Wafa. It became an independent discipline in the Islamic world, where all six trigonometric functions were known. Translations of Arabic and Greek texts led to trigonometry being adopted as a subject in the Latin West beginning in the Renaissance with Regiomontanus. The development of modern trigonometry shifted during the western Age of Enlightenment, beginning with 17th-century mathematics (Isaac Newton and James Stirling) and reaching its modern form with Leonhard Euler (1748). EtymologyThe term "trigonometry" was derived from Greek τρίγωνον trigōnon, "triangle" and μέτρον metron, "measure".[3] The modern words "sine" and "cosine" are derived from the Latin word sinus via mistranslation from Arabic (see Sine and cosine § Etymology). Particularly Fibonacci's sinus rectus arcus proved influential in establishing the term.[4] The word tangent comes from Latin tangens meaning "touching", since the line touches the circle of unit radius, whereas secant stems from Latin secans "cutting" since the line cuts the circle (see the figure at Pythagorean identities).[5] The prefix "co-" (in "cosine", "cotangent", "cosecant") is found in Edmund Gunter's Canon triangulorum (1620), which defines the cosinus as an abbreviation for the sinus complementi (sine of the complementary angle) and proceeds to define the cotangens similarly.[6][7] The words "minute" and "second" are derived from the Latin phrases partes minutae primae and partes minutae secundae.[8] These roughly translate to "first small parts" and "second small parts". AncientAncient Near EastThe ancient Egyptians and Babylonians had known of theorems on the ratios of the sides of similar triangles for many centuries. However, as pre-Hellenic societies lacked the concept of an angle measure, they were limited to studying the sides of triangles instead.[9] The Babylonian astronomers kept detailed records on the rising and setting of stars, the motion of the planets, and the solar and lunar eclipses, all of which required familiarity with angular distances measured on the celestial sphere.[10] Based on one interpretation of the Plimpton 322 cuneiform tablet (c. 1900 BC), some have even asserted that the ancient Babylonians had a table of secants but does not work in this context as without using circles and angles in the situation modern trigonometric notations will not apply.[11] There is, however, much debate as to whether it is a table of Pythagorean triples, a solution of quadratic equations, or a trigonometric table.[12] The Egyptians, on the other hand, used a primitive form of trigonometry for building pyramids in the 2nd millennium BC.[10] The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, written by the Egyptian scribe Ahmes (c. 1680–1620 BC), contains the following problem related to trigonometry:[10]

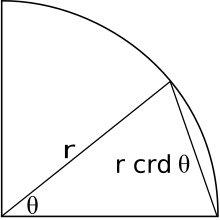

Ahmes' solution to the problem is the ratio of half the side of the base of the pyramid to its height, or the run-to-rise ratio of its face. In other words, the quantity he found for the seked is the cotangent of the angle to the base of the pyramid and its face.[10] Classical antiquity Ancient Greek and Hellenistic mathematicians made use of the chord. Given a circle and an arc on the circle, the chord is the line that subtends the arc. A chord's perpendicular bisector passes through the center of the circle and bisects the angle. One half of the bisected chord is the sine of one half the bisected angle, that is,[13] and consequently the sine function is also known as the half-chord. Due to this relationship, a number of trigonometric identities and theorems that are known today were also known to Hellenistic mathematicians, but in their equivalent chord form.[14][15] Although there is no trigonometry in the works of Euclid and Archimedes, in the strict sense of the word, there are theorems presented in a geometric way (rather than a trigonometric way) that are equivalent to specific trigonometric laws or formulas.[9] For instance, propositions twelve and thirteen of book two of the Elements are the laws of cosines for obtuse and acute angles, respectively. Theorems on the lengths of chords are applications of the law of sines. And Archimedes' theorem on broken chords is equivalent to formulas for sines of sums and differences of angles.[9] To compensate for the lack of a table of chords, mathematicians of Aristarchus' time would sometimes use the statement that, in modern notation, sin α/sin β < α/β < tan α/tan β whenever 0° < β < α < 90°, now known as Aristarchus's inequality.[16] The first trigonometric table was apparently compiled by Hipparchus of Nicaea (180 – 125 BC), who is now consequently known as "the father of trigonometry."[17] Hipparchus was the first to tabulate the corresponding values of arc and chord for a series of angles.[4][17] Although it is not known when the systematic use of the 360° circle came into mathematics, it is known that the systematic introduction of the 360° circle came a little after Aristarchus of Samos composed On the Sizes and Distances of the Sun and Moon (c. 260 BC), since he measured an angle in terms of a fraction of a quadrant.[16] It seems that the systematic use of the 360° circle is largely due to Hipparchus and his table of chords. Hipparchus may have taken the idea of this division from Hypsicles who had earlier divided the day into 360 parts, a division of the day that may have been suggested by Babylonian astronomy.[18] In ancient astronomy, the zodiac had been divided into twelve "signs" or thirty-six "decans". A seasonal cycle of roughly 360 days could have corresponded to the signs and decans of the zodiac by dividing each sign into thirty parts and each decan into ten parts.[8] It is due to the Babylonian sexagesimal numeral system that each degree is divided into sixty minutes and each minute is divided into sixty seconds.[8]  Menelaus of Alexandria (c. 100 AD) wrote in three books his Sphaerica. In Book I, he established a basis for spherical triangles analogous to the Euclidean basis for plane triangles.[15] He established a theorem that is without Euclidean analogue, that two spherical triangles are congruent if corresponding angles are equal, but he did not distinguish between congruent and symmetric spherical triangles.[15] Another theorem that he establishes is that the sum of the angles of a spherical triangle is greater than 180°.[15] Book II of Sphaerica applies spherical geometry to astronomy. And Book III contains the "theorem of Menelaus".[15] He further gave his famous "rule of six quantities".[19] Later, Claudius Ptolemy (c. 90 – c. 168 AD) expanded upon Hipparchus' Chords in a Circle in his Almagest, or the Mathematical Syntaxis. The Almagest is primarily a work on astronomy, and astronomy relies on trigonometry. Ptolemy's table of chords gives the lengths of chords of a circle of diameter 120 as a function of the number of degrees n in the corresponding arc of the circle, for n ranging from 1/2 to 180 by increments of 1/2.[20] The thirteen books of the Almagest are the most influential and significant trigonometric work of all antiquity.[21] A theorem that was central to Ptolemy's calculation of chords was what is still known today as Ptolemy's theorem, that the sum of the products of the opposite sides of a cyclic quadrilateral is equal to the product of the diagonals. A special case of Ptolemy's theorem appeared as proposition 93 in Euclid's Data. Ptolemy's theorem leads to the equivalent of the four sum-and-difference formulas for sine and cosine that are today known as Ptolemy's formulas, although Ptolemy himself used chords instead of sine and cosine.[21] Ptolemy further derived the equivalent of the half-angle formula Ptolemy used these results to create his trigonometric tables, but whether these tables were derived from Hipparchus' work cannot be determined.[21] Neither the tables of Hipparchus nor those of Ptolemy have survived to the present day, although descriptions by other ancient authors leave little doubt that they once existed.[22] Indian mathematicsSome of the early and very significant developments of trigonometry were in India. Influential works from the 4th–5th century AD, known as the Siddhantas (of which there were five, the most important of which is the Surya Siddhanta[23]) first defined the sine as the modern relationship between half an angle and half a chord, while also defining the cosine, versine, and inverse sine.[24] Soon afterwards, another Indian mathematician and astronomer, Aryabhata (476–550 AD), collected and expanded upon the developments of the Siddhantas in an important work called the Aryabhatiya.[25] The Siddhantas and the Aryabhatiya contain the earliest surviving tables of sine values and versine (1 − cosine) values, in 3.75° intervals from 0° to 90°, to an accuracy of 4 decimal places.[26] They used the words jya for sine, kojya for cosine, utkrama-jya for versine, and otkram jya for inverse sine. The words jya and kojya eventually became sine and cosine respectively after a mistranslation described above. In the 7th century, Bhaskara I produced a formula for calculating the sine of an acute angle without the use of a table. He also gave the following approximation formula for sin(x), which had a relative error of less than 1.9%: Later in the 7th century, Brahmagupta redeveloped the formula (also derived earlier, as mentioned above) and the Brahmagupta interpolation formula for computing sine values.[11] Another later Indian author on trigonometry was Bhaskara II in the 12th century. Bhaskara II developed spherical trigonometry, and discovered many trigonometric results. Bhaskara II was the one of the first to discover and trigonometric results like: Madhava (c. 1400) made early strides in the analysis of trigonometric functions and their infinite series expansions. He developed the concepts of the power series and Taylor series, and produced the power series expansions of sine, cosine, tangent, and arctangent.[27][28] Using the Taylor series approximations of sine and cosine, he produced a sine table to 12 decimal places of accuracy and a cosine table to 9 decimal places of accuracy. He also gave the power series of π and the angle, radius, diameter, and circumference of a circle in terms of trigonometric functions. His works were expanded by his followers at the Kerala School up to the 16th century.[27][28]

The Indian text the Yuktibhāṣā contains proof for the expansion of the sine and cosine functions and the derivation and proof of the power series for inverse tangent, discovered by Madhava. The Yuktibhāṣā also contains rules for finding the sines and the cosines of the sum and difference of two angles. Chinese mathematics In China, Aryabhata's table of sines were translated into the Chinese mathematical book of the Kaiyuan Zhanjing, compiled in 718 AD during the Tang dynasty.[30] Although the Chinese excelled in other fields of mathematics such as solid geometry, binomial theorem, and complex algebraic formulas, early forms of trigonometry were not as widely appreciated as in the earlier Greek, Hellenistic, Indian and Islamic worlds.[31] Instead, the early Chinese used an empirical substitute known as chong cha, while practical use of plane trigonometry in using the sine, the tangent, and the secant were known.[30] However, this embryonic state of trigonometry in China slowly began to change and advance during the Song dynasty (960–1279), where Chinese mathematicians began to express greater emphasis for the need of spherical trigonometry in calendrical science and astronomical calculations.[30] The polymath Chinese scientist, mathematician and official Shen Kuo (1031–1095) used trigonometric functions to solve mathematical problems of chords and arcs.[30] Victor J. Katz writes that in Shen's formula "technique of intersecting circles", he created an approximation of the arc s of a circle given the diameter d, sagitta v, and length c of the chord subtending the arc, the length of which he approximated as[32] Sal Restivo writes that Shen's work in the lengths of arcs of circles provided the basis for spherical trigonometry developed in the 13th century by the mathematician and astronomer Guo Shoujing (1231–1316).[33] As the historians L. Gauchet and Joseph Needham state, Guo Shoujing used spherical trigonometry in his calculations to improve the calendar system and Chinese astronomy.[30][34] Along with a later 17th-century Chinese illustration of Guo's mathematical proofs, Needham states that:

Despite the achievements of Shen and Guo's work in trigonometry, another substantial work in Chinese trigonometry would not be published again until 1607, with the dual publication of Euclid's Elements by Chinese official and astronomer Xu Guangqi (1562–1633) and the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci (1552–1610).[36] Medieval Islamic world Previous works were later translated and expanded in the medieval Islamic world by Muslim mathematicians of mostly Persian and Arab descent, who enunciated a large number of theorems which freed the subject of trigonometry from dependence upon the complete quadrilateral, as was the case in Hellenistic mathematics due to the application of Menelaus' theorem. According to E. S. Kennedy, it was after this development in Islamic mathematics that "the first real trigonometry emerged, in the sense that only then did the object of study become the spherical or plane triangle, its sides and angles."[37] Methods dealing with spherical triangles were also known, particularly the method of Menelaus of Alexandria, who developed "Menelaus' theorem" to deal with spherical problems.[15][38] However, E. S. Kennedy points out that while it was possible in pre-Islamic mathematics to compute the magnitudes of a spherical figure, in principle, by use of the table of chords and Menelaus' theorem, the application of the theorem to spherical problems was very difficult in practice.[39] In order to observe holy days on the Islamic calendar in which timings were determined by phases of the moon, astronomers initially used Menelaus' method to calculate the place of the moon and stars, though this method proved to be clumsy and difficult. It involved setting up two intersecting right triangles; by applying Menelaus' theorem it was possible to solve one of the six sides, but only if the other five sides were known. To tell the time from the sun's altitude, for instance, repeated applications of Menelaus' theorem were required. For medieval Islamic astronomers, there was an obvious challenge to find a simpler trigonometric method.[40] In the early 9th century AD, Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī produced accurate sine and cosine tables, and the first table of tangents. He was also a pioneer in spherical trigonometry. In 830 AD, Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi produced the first table of cotangents.[41][42] Muhammad ibn Jābir al-Harrānī al-Battānī (Albatenius) (853–929 AD) discovered the reciprocal functions of secant and cosecant, and produced the first table of cosecants for each degree from 1° to 90°.[43] By the 10th century AD, in the work of Abū al-Wafā' al-Būzjānī, all six trigonometric functions were used.[44] Abu al-Wafa had sine tables in 0.25° increments, to 8 decimal places of accuracy, and accurate tables of tangent values.[44] He also developed the following trigonometric formula:[45]

In his original text, Abū al-Wafā' states: "If we want that, we multiply the given sine by the cosine minutes, and the result is half the sine of the double".[45] Abū al-Wafā also established the angle addition and difference identities presented with complete proofs:[45] For the second one, the text states: "We multiply the sine of each of the two arcs by the cosine of the other minutes. If we want the sine of the sum, we add the products, if we want the sine of the difference, we take their difference".[45] He also discovered the law of sines for spherical trigonometry:[41] Also in the late 10th and early 11th centuries AD, the Egyptian astronomer Ibn Yunus performed many careful trigonometric calculations and demonstrated the following trigonometric identity:[46] Al-Jayyani (989–1079) of al-Andalus wrote The book of unknown arcs of a sphere, which is considered "the first treatise on spherical trigonometry".[47] It "contains formulae for right-handed triangles, the general law of sines, and the solution of a spherical triangle by means of the polar triangle." This treatise later had a "strong influence on European mathematics", and his "definition of ratios as numbers" and "method of solving a spherical triangle when all sides are unknown" are likely to have influenced Regiomontanus.[47] The method of triangulation was first developed by Muslim mathematicians, who applied it to practical uses such as surveying[48] and Islamic geography, as described by Abu Rayhan Biruni in the early 11th century. Biruni himself introduced triangulation techniques to measure the size of the Earth and the distances between various places.[49] In the late 11th century, Omar Khayyám (1048–1131) solved cubic equations using approximate numerical solutions found by interpolation in trigonometric tables. In the 13th century, Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī was the first to treat trigonometry as a mathematical discipline independent from astronomy, and he developed spherical trigonometry into its present form.[42] He listed the six distinct cases of a right-angled triangle in spherical trigonometry, and in his Book on the Complete Quadrilateral, he stated the law of sines for plane and spherical triangles, discovered the law of tangents for spherical triangles, and provided proofs for both these laws.[50] Nasir al-Din al-Tusi has been described as the creator of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline in its own right.[51][52][53] The law of cosines, in geometric form, can be found as propositions II.12–13 in Euclid's Elements (c. 300 BC),[54] but was not used for the solution of triangles per se. Medieval Islamic mathematicians developed a method for finding the third side of an arbitrary triangle given two sides and the included angle based on the same concept but more similar to the modern formulation of the law of cosines. A sketch of the method can be found in Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī's Book on the Complete Quadrilateral (c. 1250),[55] and the same method is described in more detail in Jamshīd al-Kāshī's Key of Arithmetic (1427).[56] Al-Kāshī also computed the sine of 1° accurate to 8 sexagesimal digits, and constructed the most accurate trigonometric tables to date, accurate to four sexagesimal places (equivalent to 8 decimal places) for each 1° of arc.[citation needed] Al-Kāshī presumably worked on Ulugh Beg's even more comprehensive trigonometric tables, with five-place (sexagesimal) entries for each minute of arc.[citation needed] Modern

European renaissance and beyondIn 1342, Levi ben Gershon, known as Gersonides, wrote On Sines, Chords and Arcs, in particular proving the sine law for plane triangles and giving five-figure sine tables.[57] A simplified trigonometric table, the "toleta de marteloio", was used by sailors in the Mediterranean Sea during the 14th-15th Centuries to calculate navigation courses. It is described by Ramon Llull of Majorca in 1295, and laid out in the 1436 atlas of Venetian captain Andrea Bianco. Regiomontanus was perhaps the first mathematician in Europe to treat trigonometry as a distinct mathematical discipline,[58] in his De triangulis omnimodis written in 1464, as well as his later Tabulae directionum which included the tangent function, unnamed. The Opus palatinum de triangulis of Georg Joachim Rheticus, a student of Copernicus, was probably the first in Europe to define trigonometric functions directly in terms of right triangles instead of circles, with tables for all six trigonometric functions; this work was finished by Rheticus' student Valentin Otho in 1596. In the 17th century, Isaac Newton and James Stirling developed the general Newton–Stirling interpolation formula for trigonometric functions. In the 18th century, Leonhard Euler's Introduction in analysin infinitorum (1748) was mostly responsible for establishing the analytic treatment of trigonometric functions in Europe, deriving their infinite series and presenting "Euler's formula" eix = cos x + i sin x. Euler used the near-modern abbreviations sin., cos., tang., cot., sec., and cosec. Prior to this, Roger Cotes had computed the derivative of sine in his Harmonia Mensurarum (1722).[59] Also in the 18th century, Brook Taylor defined the general Taylor series and gave the series expansions and approximations for all six trigonometric functions. The works of James Gregory in the 17th century and Colin Maclaurin in the 18th century were also very influential in the development of trigonometric series. See also

Citations and footnotes

References

Further readingWikiquote has quotations related to History of trigonometry.

|