|

History of Buffalo, New York

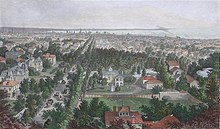

Buffalo is the county seat of Erie County, and the second most populous city in the U.S. state of New York, after New York City. Originating around 1789 as a small trading community inhabited by the Neutral Nation near the mouth of Buffalo Creek, the city, then a town, grew quickly after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, with the city at its western terminus. Its position at the eastern end of Lake Erie strengthened the economy, based on grain milling and steel production along the southern shores and in nearby Lackawanna. In the dawn of the 20th century, Buffalo was one of the most populous cities in the United States. It had hosted the Pan-American Exposition in 1901 and later became a center for the automotive industry. Later, the opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway combined with the effects of suburbanization, deindustrialization, and globalization led to the decline of the city's chief industries. The city lost over half of its population from 1950 to 2010. Buffalo retains many industries and has developed a diverse economy based upon advanced manufacturing, healthcare and education. Etymology

The City of Buffalo, formerly known as Buffalo Creek, received its name from the creek that flows through it. However, the origin of the creek's name is unclear, with several unproven theories existing. Early French explorers reported the abundance of buffalo on the Eastern shore of Lake Erie, but their presence on the banks of Buffalo Creek is still a matter of debate, although American Bison did range into western NY state at one time. Neither the Seneca name Teyohoseroron (the Place of the Basswoods) nor the French name Rivière aux Chevaux (River of Horses) survived, so the current name likely dates to the British occupation which began with the capture of Fort Niagara in 1759. Another theory holds that a Seneca Indian lived there, either whose name meant buffalo, or who had the physical characteristics of a buffalo, and was translated as such by the English settlers. The stream where he lived became Buffalo's Creek. Unlike other nearby creeks such as Scajaquada Creek and Smoke's Creek which were named after actual historic figures, there is no known reference to any Native American named Buffalo. Also given credence by local historians at one time was the possibility that an interpreter mistranslated the Native American word for "beaver" as "buffalo," the words being very similar, at a treaty-signing at present-day Rome, New York in 1784. The theory assumes that because there were beaver here, the creek was probably called Beaver Creek rather than Buffalo Creek.  Another theory holds that the name is an anglicized form of the French name Beau Fleuve (beautiful river), which was supposedly an exclamation uttered by Louis Hennepin when he first saw the Niagara River. This is a relatively recently proposed theory (1909) and is unlikely, as no period sources contain this quote. The earliest known name origin theory is an anecdote originally published in Sheldon Ball's Buffalo in 1825, about a party of explorers whose guide shoots a horse and passes it off as bison meat. Despite many years of speculation and garbling of previous debate, more recently available sources indicate that the name Buffalo Creek was in common use on the Niagara Frontier by 1764, as John Montresor referenced 'Buffalo Creek' in his journal of that year.[2] The name may have originated with an English speaking person sometime between 1759 and 1764, possibly after seeing animal bones, thought to be bison but possibly elk or moose or domesticated cattle, at the salt lick called Sour Springs located at the head of navigation about 6 miles up the creek. An alternate explanation put forward in late 2020, is that the origin comes from the French “Riviere du Bois Blanc” meaning “River of White Wood” being used to describe the creek. Bois Blanc pronounced “Boblo” or “Bob Low” around the Great Lakes, morphed into “Buffalo” when the British took control of the region in 1759–1760. These theories are summarized and ranked on a pamphlet developed by The Buffalo History Museum.[3] Pre-Columbian era to European explorationAmerindian CrossroadsThe first inhabitants of New York State are believed to have been nomadic Paleo-Indians who migrated after the disappearance of Pleistocene glaciers during or before 7000 BCE.[citation needed] The societies of the Native Forest dwellers we know as Native Americans or First Nations made highways of the Great Lakes' streams and were far more social than their reputed penchant for warfare, cruelty, and collecting scalps would suggest. Their canoes were built from lightweight birch bark, or far more often, Elm, the farther south the tribe, the more likely Elm was the material used for many purposes including the canoes. Buffalo, near the throat of the Niagara River, was a popular campsite for voyaging tribesmen, in a culture which often went on walk-abouts, touring neighboring lands and conducting the widespread practice of boy-meets-girl, trading of regional commodities.[a]  Prior to European colonization by French settlers, the region's inhabitants were an Iroquoian tribal offshoot called the Wenro people or 'Wenrohronon', who lived along the south shore of Lake Ontario and east end of Lake Erie and a bit of its southern shore. The population of the Wenro was small by comparison to other Iroquoian tribes the French encountered and reported upon, possibly because they'd only recently split off from other groups or because they'd suffered the misfortunes of war. They were possibly (most likely) a sub-group of the main Neutral Confederacy which had colonized the opposite shore, or possibly relatives of the great abutting neighboring Erie Nation,[b] which extended southwesterly through most of present-day Ohio, Western Pennsylvania and West Virginia. The American Heritage Book of Indians points out there are opposing (on the surface) contradictory theories[c] of the origination and the migration of the Iroquois and Iroquoian peoples that came to inhabit the region around Buffalo and the Niagara River.[d] The French found the Neutral groups helpful in mediating disputes with other tribes—in particular the League of the Iroquois which became sworn enemies of the French from their first meeting in 1609.[e] By comparison, the Huron also an Iroquoian people, were often at odds with the Iroquois once European traders offered highly desired goods for furs, especially water proof Beaver pelts[f] About 1651 the Iroquois Confederacy declared war on the Neutrals; by 1653, the Confederacy, particularly the Senecas, had practically annihilated the Neutrals[4][5] and the splinter tribe of Wenro people. The Wenro's area was subsequently populated by the Seneca tribe. Also in 1653 the large and populous Erie tribe, having taken in survivors of the Huron, Neutral, Wenro, and Tabacco peoples—Iroquoian peoples one and all, with traditions of adopting outsiders—received demands to send Neutrals to the Iroquois and instead launched a pre-emptive attack on the League, kicking off three years of desperate warfare that eventually shattered the Erie and bled the Iroquois of much of their strength.[g] Ohio and Western Pennsylvania became nearly vacant Iroquois hunting grounds, exploited for furs, but ten years later the Iroquois, having also adopted tribal members of peoples they'd recently thrashed, found themselves in a new war with the Susquehannocks who lived down below the Allegheny Front, the escarpment above most of today's central Pennsylvania along the Susquehanna River valleys—another people believed to have significantly outnumbered the Iroquois[h] —so warring along the Susquehanna Valley from lower New York to Maryland through central Pennsylvania. In 1667-68 the Susquehannocks nearly wiped out two of the Five Iroquois people. At that point the Susquehannock's suffered one or more horrendous plagues, losing up to 90% of their population and military capabilities, and by 1672 the Iroquois became the proverbial 'Last Man Standing' in the Northern Beaver Wars. First Europeans, 1758–1793Most of western New York was granted by Charles II of England to the Duke of York (later King James II & VII), but the first European settlement in what is now Erie County was by the French, at the mouth of Buffalo Creek in 1758. Its buildings were destroyed a year later by the evacuating French after the British captured Fort Niagara. The British took control of the entire region in 1763, at the conclusion of the French and Indian War. In 1764, British military engineer John Montresor made an inspection tour of Buffalo Creek before determining on a site for a fortification on the opposite shore. After the 1779 Sullivan Expedition, the British settled Seneca refugees in several villages on Buffalo Creek in the spring of 1780. The first white settlers along the creek were prisoners captured during the Revolutionary War.[6] The first resident and landowner of Buffalo with a permanent presence was Captain William Johnston,[7] a white Iroquois interpreter who had been in the area since the days after the Revolutionary War and who the Senecas granted creekside land as a gift of appreciation. His house stood at present-day Washington and Seneca streets.[8] Former enslaved man Joseph "Black Joe" Hodges,[9][10] and Cornelius Winney, a Dutch trader from Albany who arrived in 1789, were early settlers along the mouth of Buffalo Creek.[11] They set up a log cabin store there in 1789 for trading with the Native American community. The British retained control of the area and prevented further settlement by Americans until their evacuation of Fort Niagara in 1796. Erie Canal, grain and commerceHolland Land Purchase, 1793–1825 On July 20, 1793, the Holland Land Purchase, including the land of present-day Buffalo, was completed with land being acquired from the Seneca Indians and brokered by Dutch investors from Holland.[13] The Treaty of Big Tree removed Iroquois title to lands west of the Genesee River in 1797.[14] Although other Senecas were involved in ceding their land, the most famous today is Red Jacket, who died in Buffalo in 1830. His grave is in Forest Lawn Cemetery. In the fall of 1797, Joseph Ellicott, the architect who helped survey Washington, D.C., with brother Andrew,[15][16] was appointed as the Chief of Survey for the Holland Land Company.[17] Over the next year, he began to survey the tract of land at the mouth of Buffalo Creek. This was completed in 1803,[18] and the new village boundaries extended from the creekside in the south to present-day Chippewa Street in the north and Carolina Street to the west,[19] which is where most settlers remained for the first decade of the 19th century.[citation needed] Starting in 1801, parcels were sold through the Holland Land Companies office in Batavia, New York. The settlement was initially called Lake Erie, then Buffalo Creek, soon shortened to Buffalo. Although the company named the settlement "New Amsterdam," the name did not catch on, reverting to Buffalo within ten years.[20][19] Buffalo had the first road to Pennsylvania built in 1802 for migrants passing through to the Connecticut Western Reserve in Ohio.[21] On October 11, 1803, Ellicott sold Lot 41, Township 11, range 8 in the village of Buffalo to Cyrenius Chapin, a physician, for $346.50. It was one of the first properties Ellicott sold in the village proper and made Chapin Buffalo’s first physician. In 1805, he and his wife Sylvia built the village’s sixteenth frame building, an office/home, on their lot just a half mile from the Seneca reservation on Buffalo Creek.[22][23] The doctor became a friend to the Senecas, an active politician, and hero in the War of 1812.[24] In 1804, Ellicott completed his design of a radial grid plan that would branch out from the village forming bicycle-like spokes, interrupted by diagonals, like the system used in the nation's capital.[25] It is one of only three radial street patterns in the US [citation needed]. In the middle of the village was the intersection of eight streets, in what would become Niagara Square. Several blocks to the southeast he designed a semicircle fronting Main Street with an elongated park green, formerly his estate.[26][27] This would be known as Shelton Square,[28] at that time the center of the city (which would be dramatically altered in the mid-20th century),[29] with the intersecting streets bearing the names of Dutch Holland Land Company members,[30][i] today Erie, Church and Niagara streets.[26] Lafayette Square also lies one block to the north, which was then bounded by streets bearing Iroquois names.[18] In 1804, Buffalo's population was estimated at 400, similar to Batavia, but Erie County's growth was behind Chautauqua, Genesee and Wyoming counties.[31] Neighboring village Black Rock to the northwest (today a Buffalo neighborhood) was also an important center.[26] Horatio J. Spafford noted in A Gazetteer of the State of New York that in fact, despite the growth the village of Buffalo had, Black Rock "is deemed a better trading site for a great trading town than that of Buffalo," especially when considering the regional profile of mundane roads extending eastward.[31] Before the east-to-west turnpike[further explanation needed] was completed, travelling from Albany to Buffalo would take a week,[32] while even a trip from nearby Williamsville to Batavia could take upwards of three days.[33][j] According to an early resident, the village had sixteen residences, a schoolhouse and two stores in 1806, primarily near Main, Swan and Seneca streets.[34] There were also blacksmith shops, a tavern and a drugstore.[35] The streets were small at 40 feet wide, and the village was still surrounded by woods.[36] The first lot sold by the Holland Land Company was on September 11, 1806, to Zerah Phelps.[37] By 1808, lots would sell from $25 to $50.[38] Although slavery was rare in the state, limited instances of slavery had taken place in Buffalo during the early part of the 19th century. General Peter Buell Porter is said to have had five slaves during his time in Black Rock, and several news ads also advertised slaves for sale.[39] In 1808, Niagara County was established with Buffalo as its county seat. In 1810, the Town of Buffalo was formed from the western part of the Town of Clarence. Also in 1810, a courthouse was built. By 1811, the population was 500, with many people farming or doing manual labor.[40] The first newspaper to be published was the Buffalo Gazette in October that same year.[38] On December 30, 1813, during the War of 1812, British troops and their Native American allies first captured the village of Black Rock, and then the rest of Buffalo. On December 31, 1813, most of Buffalo and the village of Black Rock were burned by the British after the Battle of Buffalo.[41][42] The battle and subsequent fire was in response to the unprovoked destruction of Niagara-on-the-Lake, then known as "Newark," by American forces.[43][44] On August 4, 1814, British forces under Lt. Colonel John Tucker and Lt. Colonel William Drummond, General Gordon Drummond's nephew, attempted to raid Black Rock and Buffalo as part of a diversion to force an early surrender at Fort Erie the next day, but were defeated by a small force of American riflemen under Major Lodwick Morgan at the Battle of Conjocta Creek, and withdrew back into Canada. Consequently, Fort Erie's siege under Gordon Drummond later failed, and British forces withdrew. Though only three buildings remained in the village, rebuilding was swift, finishing in 1815.[45][46] Buffalo gradually rebuilt itself and by 1816 had a new courthouse. In 1818, the eastern part of the town was lost to form the Town of Amherst. Erie County was formed out of Niagara County in 1821, retaining Buffalo as the county seat. Erie Canal, 1825–1850 On October 26, 1825,[47] the Erie Canal was completed, formed from part of Buffalo Creek,[48] with Buffalo a port-of-call for settlers heading westward.[49] Buffalo became the western end of the 524-mile waterway starting at New York City. At the time, the population was about 2,400.[50] By 1826, the 130 sq. mile Buffalo Creek Reservation at the western border of the village was transferred to Buffalo.[51] The Erie Canal brought a surge in population and commerce, which led Buffalo to incorporate as a city in 1832.[52][53] The population in 1840 was 18,213.[54] The canal area was mature by 1847, with passenger and cargo ship activity leading to congestion in the harbor.[55] On 1 June 1843, the world's first steam-powered grain elevator was put into service by a local merchant, Joseph Dart Jr., and an engineer, Robert Dunbar. The "Dart Elevator" would remain standing until 1862, when it burned down. During the 1840s and 1850s, more than a dozen grain elevators were built in Buffalo's harbor, most of them designed by Dunbar.[56] As the anti-slavery movement grew in the U.S., Buffalo also emerged as a gathering place for abolitionists. In 1843, the city served as the site of the Liberty Party[57] convention and the National Convention of Colored Citizens.[58] The mid-1800s saw a population boom, with the city doubling in size from 1845 to 1855.[59] In 1855, almost two-thirds of the city's population were foreign-born immigrants, largely a mix of unskilled or educated Irish and German Catholics, who began self-segregating in different parts of the city. The Irish immigrants planted their roots along the railroad-heavy Buffalo River and Erie Canal to the southeast, to which there is still a heavy presence today; German immigrants found their way to the East Side, living a more laid-back, residential life.[60] Some immigrants were apprehensive about the change of environment and left the city for the western region, while others tried to stay behind in the hopes of expanding their native cultures.[61] Fugitive black slaves began to make their way northward to Buffalo in the 1840s, and many of them settled on the city's East Side.[62] Buffalo was a terminus of the Underground Railroad, an informal series of safe houses for African-Americans escaping slavery in the mid-19th century. Buffalonians helped many fugitives cross the Niagara River to Fort Erie, Ontario, Canada and freedom. In 1845, construction began on the Macedonia Baptist Church, a meeting spot in the Michigan and William Street neighborhood where blacks first settled.[63] Political activity surrounding the anti-slavery movement took place in Buffalo during this time, including conventions held by the National Convention of Colored Citizens and the Liberty Party and its offshoots.[64] Buffalo was a terminus point of the Underground Railroad with many fugitive slaves crossing the Niagara River to Fort Erie, Ontario in search of freedom.[65]  During the 1840s, Buffalo's port continued to develop. Both passenger and commercial traffic expanded with some 93,000 passengers heading west from the port of Buffalo.[66][better source needed] Grain and commercial goods shipments led to repeated expansion of the harbor.[citation needed] In 1843, the world's first steam-powered grain elevator was constructed by local merchant Joseph Dart and engineer Robert Dunbar.[67] "Dart's Elevator" enabled faster unloading of lake freighters along with the transshipment of grain in bulk from barges, canal boats, and rail cars.[68] Millard Fillmore, who had taken up permanent residence in Buffalo in 1822 and represented the area in Congress on and off from 1832 to 1842, became the first chancellor of the University of Buffalo upon its founding in 1846, now known as SUNY University at Buffalo. Fillmore would be elected vice president in the election of 1848 and would eventually become the 13th President of the United States upon the death of Zachary Taylor in 1850. Railroads and industry, 1850–1900 By 1850, the city's population was 81,000.[53] In 1853, Buffalo annexed Black Rock, which had been Buffalo's fierce rival for the canal terminus. During the 19th century, thousands of pioneers going to the western United States debarked from canal boats to continue their journey out of Buffalo by lake or rail transport. During their stopover, many experienced the pleasures and dangers of Buffalo's notorious Canal district. The Erie Canal's peak year was 1855, when 33,000 commercial shipments took place. In 1860, many railway companies and lines crossed through and terminated in Buffalo. Major ones were the Buffalo, Bradford and Pittsburgh Railroad (1859), Buffalo and Erie Railroad and the New York Central Railroad (1853).[69] During this time, Buffalonians controlled a quarter of all shipping traffic on Lake Erie, and shipbuilding was a thriving industry for the city.[70] Later, the Lehigh Valley Railroad would have its line terminate at Buffalo in 1867. Buffalo was part of and the seat of Niagara County until the legislature passed an act separating the two on April 2, 1861.[71] Grover Cleveland lived in Buffalo from 1854 until 1882, and served as Buffalo's mayor from 1882 until 1883 before eventually becoming the 22nd and 24th President of the United States, winning the popular vote in 1884, 1888, and 1892. Steel industry and declineCity of Light, 1900–1957 Around the start of the 20th century, Buffalo was a growing city with a burgeoning economy. Immigrants came from Ireland, Italy, Germany, and Poland to work in the steel and grain mills which had taken advantage of the city's critical location at the junction of the Great Lakes and the Erie Canal. Hydroelectric power harnessed from nearby Niagara Falls made Buffalo the first American city to have widespread electric lighting yielding it the nickname, the "City of Light". Electricity was used to dramatic effect at the Pan-American Exposition in 1901.  The Pan-American was also notable for being the scene of the assassination of United States President William McKinley. He was shot by Leon Czolgosz on September 6, 1901, at the Exposition, and died in Buffalo on the 14th. Theodore Roosevelt was then sworn in on September 14, 1901, at the Ansley Wilcox Mansion, now the Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site, becoming one of only four presidents to be sworn in outside of the nation's capital. In 1918, the upgrade of the Erie Canal into the New York State Barge Canal meant that the canal now ended where Tonawanda Creek met the Niagara River. The advent of powered tugboats meant that barges could more easily move upstream in the upper portion of the river. As a result, the final section of the old canal, which had run alongside the river from Tonawanda to Buffalo – and which had been so critical to the city's growth nearly a century earlier – became obsolete and was gradually filled in over time.[72] The opening of the Peace Bridge linking Buffalo with Fort Erie, Ontario on August 7, 1927, was an occasion for significant celebrations. When it opened, Buffalo and Fort Erie each became the chief port of entry to their respective countries from the other. The bridge remains one of North America's important commercial ports with four thousand trucks crossing it daily. The Great Depression of 1929-39 saw severe unemployment, especially among working-class men. The New Deal relief programs operated full force. The city became a stronghold of labor unions and the Democratic Party.[73] Buffalo's City Hall, an Art Deco masterpiece, was dedicated on July 1, 1932. During World War II, Buffalo saw the return of prosperity and full employment due to its position as a manufacturing center.[74][75] As one of the most populous cities of the 1950s, Buffalo's economy revolved almost entirely on its manufacturing base. Major companies such as Republic Steel and Lackawanna Steel employed tens of thousands of Buffalonians. Integrated national shipping routes would use the Soo Locks near Lake Superior and a vast network of railroads and yards that crossed the city. Suburbanization and decline, 1957–2010The city's population gradually began to decline in the decades after World War II. A key cause was suburban migration, which was a major national trend at the time. Race riots rocked the city in 1967,[76] and while the city's population declined in the 1960 census for the first time in its history, Erie County as a whole continued growing through the 1970 census. Another factor was the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1957. Goods which had previously passed through Buffalo could now bypass it using a series of canals and locks, reaching the ocean via the St. Lawrence River. Lobbying by local businesses and interest groups against the St. Lawrence Seaway began in the 1920s, long before its construction.[77] Shipbuilding in Buffalo, such as the American Ship Building Company, shut down in 1962, ending an industry that had been a sector of the city's economy since 1812, and a direct result of reduced waterfront activity.[78] The city, which boasted over half a million people at its peak, saw its population decline by some 50% by 2010 as industries shut down and people left the Rust Belt for the employment opportunities of the South and West. Erie Country has lost population in every census year since 1970. The post-war rise of the automobile also saw the city's landscape re-shaped. The Buffalo Skyway opened in 1953 and the first portion of the Niagara Thruway opened in 1959, using much of the route of the old Erie Canal alongside the river. Meanwhile, the region obtained a professional football franchise, the Buffalo Bills, that began play in 1960, and a professional hockey franchise, the Buffalo Sabres, that began play in 1970. A basketball franchise, the Buffalo Braves, called the city home from 1970 to 1978, and the city opened a new baseball stadium in 1988 in an unsuccessful effort to attract a major-league baseball team. On July 3, 2003, at the climax of a fiscal crisis, the Buffalo Fiscal Stability Authority was established[79] to oversee the finances of the city. Initially established as a "hard control board," they froze the wages of city employees, and were required approve or reject all major expenditures. After a period of severe financial stress, Erie County, where Buffalo resides, was assigned a Fiscal Stability Authority on July 12, 2005. As a "soft control board," however, they act only in an advisory capacity.[80] Both Authorities were established by New York State. In November 2005, Byron Brown was elected Mayor of Buffalo. He is the first African-American to hold this office. Modern eraSigns of recovery, 2010–present As of 2020, there are significant signs that Buffalo's decline may have bottomed out over the past decade, and there are increasing signs of growth in the city and region. The 2020 census was the first in 70 years that saw both Buffalo and Erie County gain population.[81] The area was not as significantly affected by the Great Recession from 2007 to 2009 as much of the nation, in part because the city never experienced the major housing bubble that other cities did. The Canalside neighborhood started developing in 2010, with an uptick in construction projects including the LECOM Harborcenter. 2012 saw the end of the "control period" in which the Buffalo Financial Stability Authority reverted to an advisory role after the city met the legal requirements for financial stability.[82] New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced the Buffalo Billion initiative in 2012 to help change the "psychology" in the region, and Tesla now operates the Giga New York factory that was completed in 2016–17. The Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus has become a significant employer in the city. An important factor in the revitalization of the city was the 2017 reform of the zoning code, including the elimination of costly parking minimums, which had hindered development for many years.[83] The city has also apparently had more success in recent years in retaining or attracting younger residents, with the low cost of living being seen as a factor. A survey of Western New York residents in December 2018 found that a remarkable 87 percent of residents believed the area was generally headed in the right direction.[84] On May 14, 2022, a mass shooting occurred at a Tops Friendly Markets supermarket in Buffalo. Ten people died, and three others were injured, in what officials described as a racially motivated attack by a white supremacist inspired by the Christchurch mosque shootings in New Zealand and other far-right related attacks.[85] 34 people in the Buffalo region died in the late December 2022 North American winter storm.[86][87] See alsoNotes

References

Works cited

Bibliography

Further reading

Old primary sources

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||