|

Hispanic Monarchy (political entity)

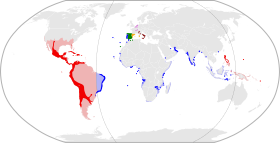

The Hispanic Monarchy (Monarquía Hispánica in Spanish), also known as Catholic Monarchy[1] and historically referred to as Monarchy of Spain[a], was the political entity encompassing the territories and dependencies of the Spanish Empire between 1479 and 1716. These regions maintained distinct, individual public institutions, councils, and legal systems, but were united under the control of a superior entity (the King of Spain)[2] and common state institutional structures. This monarchy was administered under a polysynodial system of councils. The Spanish monarch acted as king (or with the corresponding title) according to the political constitution of each kingdom, state, or lordship,[3] and thus, their formal power varied from one territory to another. However, they acted as a unified monarch over all the territories of the monarchy,[4] almost like a Composite Monarchy. The Monarchy included the Crown of Castile — with Granada, Navarre and the kingdoms of the Indies — and Aragon — with Sicily, Naples, Sardinia, and the State of the Presidi —, Portugal and its overseas territories between 1580 and 1640, the territories of the Burgundian Circle except between 1598–1621 — Franche-Comté, the Netherlands, as well as Charolais —, the Duchy of Milan, the Marquisate of Finale, the Spanish East Indies, and Spanish Africa.[5][6] The monarchy ended with the Treaties of Utrecht and Baden (1713–1714) and the Nueva Planta Decrees (1707–1716),[7] which produced a break in the system by implementing greater homogeneity and political centralization, relegating the polysynodial system.[8][9] HistoryThe Monarchy of Spain was born in 1479 from the dynastic union of the Crown of Castile and the Crown of Aragon through the marriage of their respective sovereigns, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, known as the Catholic Monarchs. Since then, the Catholic Monarchy, as it was known after the papal bull of Alexander VI in 1494, began adding various "Kingdoms, States, and Lordships" in the Iberian Peninsula, the rest of Europe, and the Americas until it became, under the Habsburg kings, the most powerful monarchy of its time. In 1580, Philip II incorporated the Kingdom of Portugal into the Monarchy, thereby bringing all of Spain—one of the meanings the term acquired then, although it was also common, since the Catholic Monarchs, to identify Spain with the crowns of Aragon and Castile—under the sovereignty of a single monarch. As Francisco de Quevedo noted in España defendida, a work published in 1609, "properly, Spain is composed of three crowns: Castile, Aragon, and Portugal." Regarding its structure, the Hispanic Monarchy was a composite monarchy where the "Kingdoms, States, and Lordships" that comprised it were united according to the formula aeque principaliter (or 'differentiated union'),[10] "under which the constituent kingdoms continued after their union being treated as distinct entities, so that they retained their own laws, charters, and privileges. 'The kingdoms are to be ruled and governed,' writes Solórzano, 'as if the king who holds them together were only king of each of them' [...] In all these territories, it was expected, and indeed it was imposed as an obligation, that the king maintain the distinctive status and identity of each one of them." The respect for territorial jurisdictions did not prevent a strengthening of the royal authority and power of the monarch in each kingdom in particular.[11] Despite the respect and jurisdictional autonomy, there existed a common policy or directive that had to be obeyed, embodied by diplomacy and defense, with the Crown of Castile occupying the central and preeminent position over the others.[12] Since the time of the Catholic Monarchs, there was a renewed sentiment of restoring Roman or Visigothic Hispania, which the kings of León had evoked with the title Imperator totius Hispaniae,[13][14] and the same kings spread the notion of the recovery of ancient Hispania under the same monarch. Notes

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia