|

Hashimoto's thyroiditis

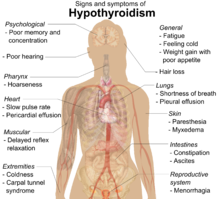

Hashimoto's thyroiditis, also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, Hashimoto's disease and autoimmune thyroiditis, is an autoimmune disease in which the thyroid gland is gradually destroyed.[7][1] Early on, symptoms may not be noticed.[3] Over time, the thyroid may enlarge, forming a painless goiter.[3] Most people eventually develop hypothyroidism with accompanying weight gain, fatigue, constipation, hair loss, and general pains.[1] After many years the thyroid typically shrinks in size.[1] Potential complications include thyroid lymphoma.[2] Further complications of hypothyroidism can include high cholesterol, heart disease, heart failure, high blood pressure, myxedema, and potential problems in pregnancy.[1] Hashimoto's thyroiditis is thought to be due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors.[5][8] Risk factors include a family history of the condition and having another autoimmune disease.[3] Diagnosis is confirmed with blood tests for TSH, Thyroxine (T4), antithyroid autoantibodies, and ultrasound.[3] Other conditions that can produce similar symptoms include Graves' disease and nontoxic nodular goiter.[6] Hashimoto's is typically not treated unless there is hypothyroidism, or the presence of a goiter, when it may be treated with levothyroxine.[6][3] Those affected should avoid eating large amounts of iodine; however, sufficient iodine is required especially during pregnancy.[3] Surgery is rarely required to treat the goiter.[6] Hashimoto's thyroiditis has a global prevalence of 7.5%, and varies greatly by region.[9] The highest rate is in Africa, and the lowest in Asia.[9] In the US white people are affected more often than black. It is more common in low to middle income groups. Females are more susceptible with a 17.5% rate of prevalence compared to 6% in males.[9] It is the most common cause of hypothyroidism in developed countries.[10] It typically begins between the ages of 30 and 50.[3][4] Rates of the disease have increased.[9] It was first described by the Japanese physician Hakaru Hashimoto in 1912.[11] Studies in 1956 discovered that it was an autoimmune disorder.[12] Signs and symptoms Signs Early stages of autoimmune thyroiditis may have a normal physical exam with or without a goiter.[13] A goiter is a diffuse, often symmetric, swelling of the thyroid gland visible in the anterior neck that may develop.[13] The thyroid gland may become firm, large, and lobulated in Hashimoto's thyroiditis, but changes in the thyroid can also be non-palpable.[14] Enlargement of the thyroid is due to lymphocytic infiltration, and fibrosis.[15] While their role in the initial destruction of the follicles is unclear, antibodies against thyroid peroxidase or thyroglobulin are relevant, as they serve as biomarkers for detecting the disease and its severity.[16] They are thought to be the secondary products of the T cell-mediated destruction of the gland.[5] As lymphocytic infiltration progresses, patients may exhibit signs of hypothyroidism in multiple bodily systems, including, but not limited to, a larger goiter, weight gain, cold intolerance, fatigue, myxedema, constipation, menstrual disturbances, pale or dry skin, and dry, brittle hair, depression, and ataxia.[13][10] Extended thyroid hormone deficiency may lead to muscle fibre changes, with fast-twitching type II being replaced by slow-twitching type-I fibers, resulting in muscle weakness, muscle pain, stiffness, and rarely, pseudohypertrophy.[17] While rare, more serious complications of the hypothyroidism resulting from autoimmune thyroiditis are pericardial effusion, pleural effusion, both of which require further medical attention, and myxedema coma, which is an endocrine emergency.[10] Patients with goiters who have had autoimmune thyroiditis for many years might see their goiter shrink in the later stages of the disease due to destruction of the thyroid.[1] Graves disease may occur before or after the development of autoimmune thyroiditis.[18] SymptomsMany symptoms are attributed to the development of Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Symptoms can include: fatigue, weight gain, pale or puffy face, feeling cold, joint and muscle pain, constipation, dry and thinning hair, heavy menstrual flow or irregular periods, depression, a slowed heart rate, problems getting pregnant, miscarriages,[19] and myopathy.[17] Some patients in the early stage of the disease may experience symptoms of hyperthyroidism due to the release of thyroid hormones from intermittent thyroid destruction[10][20] (aka destructive thyrotoxicosis).[5] While most symptoms are attributed to hypothyroidism, similar symptoms are observed in Hashimoto's patients with normal thyroid hormone levels.[21][22][23][15] According to one study, these symptoms may include lower quality of life, and issues of the "digestive system (abdominal distension, constipation and diarrhea), endocrine system (chilliness, gain weight and facial edema), neuropsychiatric system (forgetfulness, anxiety, depressed, fatigue, insomnia, irritability, and indifferent [sic]) and mucocutaneous system (dry skin, pruritus, and hair loss)."[24] In non-medical settings, the term "flare" is used to refer to a sudden exacerbation of symptoms, whether hyper or hypo.[25] CausesThe causes of Hashimoto's thyroiditis are complex. Around 80% of the risk of developing an autoimmune thyroid disorder is due to genetic factors, while the remaining 20% is related to environmental factors (such as iodine, drugs, infection, stress, radiation).[26] GeneticsThyroid autoimmunity can be familial.[27] Many patients report a family history of autoimmune thyroiditis or Graves' disease.[13] The strong genetic component is borne out in studies on monozygotic twins,[10] with a concordance of 38–55%, with an even higher concordance of circulating thyroid antibodies not in relation to clinical presentation (up to 80% in monozygotic twins). Neither result was seen to a similar degree in dizygotic twins, offering strong favour for high genetic etiology.[28] The genes implicated vary in different ethnic groups[29] and the impact of these genes on the disease differs significantly among people from different ethnic groups. A gene that has a large effect in one ethnic group's risk of developing Hashimoto's thyroiditis might have a much smaller effect in another ethnic group.[28] The incidence of autoimmune thyroid disorders is increased in people with chromosomal disorders, including Turner, Down, and Klinefelter syndromes.[26] HLA genesThe first gene locus associated with autoimmune thyroid disease was the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region on chromosome 6p21. It encodes human leukocyte antigens (HLAs). Specific HLA alleles have a higher affinity to auto-antigenic thyroidal peptides and can contribute to autoimmune thyroid disease development. Specifically, in Hashimoto's disease, aberrant expression of HLA II on thyrocytes has been demonstrated. They can present thyroid autoantigens and initiate autoimmune thyroid disease.[29] Susceptibility alleles are not consistent in Hashimoto's disease. In Caucasians, various alleles are reported to be associated with the disease, including DR3, DR5, and DQ7.[30][31] CTLA-4 genesCTLA-4 is the second major immune-regulatory gene related to autoimmune thyroid disease. CTLA-4 gene polymorphisms may contribute to the reduced inhibition of T-cell proliferation and increase susceptibility to autoimmune response.[32] CTLA-4 is a major thyroid autoantibody susceptibility gene. A linkage of the CTLA-4 region to the presence of thyroid autoantibodies was demonstrated by a whole-genome linkage analysis.[33] CTLA-4 was confirmed as the main locus for thyroid autoantibodies.[34] PTPN22 genePTPN22 is the most recently identified immune-regulatory gene associated with autoimmune thyroid disease. It is located on chromosome 1p13 and expressed in lymphocytes. It acts as a negative regulator of T-cell activation. Mutation in this gene is a risk factor for many autoimmune diseases. Weaker T-cell signaling may lead to impaired thymic deletion of autoreactive T cells, and increased PTPN22 function may result in inhibition of regulatory T cells, which protect against autoimmunity.[35] Immune-related genesIFN-γ promotes cell-mediated cytotoxicity against thyroid mutations causing increased production of IFN-γ were associated with the severity of hypothyroidism.[36] Severe hypothyroidism is associated with mutations leading to lower production of IL-4 (Th2 cytokine suppressing cell-mediated autoimmunity),[37] lower secretion of TGF-β (inhibitor of cytokine production),[38] and mutations of FOXP3, an essential regulatory factor for the regulatory T cells (Tregs) development.[39] Development of Hashimoto's disease was associated with mutation of the gene for TNF-α (stimulator of the IFN-γ production), causing its higher concentration.[40] Existential (aka endogenous environmental)SexStudy of healthy Danish twins divided to three groups (monozygotic and dizygotic same sex, and opposite sex twin pairs) estimated that genetic contribution to thyroid peroxidase antibodies susceptibility was 61% in males and 72% in females, and contribution to thyroglobulin antibodies susceptibility was 39% in males and 75% in females.[41] The high female predominance in thyroid autoimmunity may be associated with the X chromosome. It contains sex and immune-related genes responsible for immune tolerance.[42] A higher incidence of thyroid autoimmunity was reported in patients with a higher rate of X-chromosome monosomy in peripheral white blood cells.[43] X-chromosome inactivationAnother potential mechanism might be skewed X-chromosome inactivation,[5] leading to the escape of X-linked self-antigens from presentation in the thymus and loss of T-cell tolerance.[citation needed] PregnancyIn one population study, two or more births were a risk factor for developing autoimmune hypothyroidism in pre-menopausal women.[44] EnvironmentalMedicationsCertain medications or drugs have been associated with altering and interfering with thyroid function. There are two main mechanisms of interference:[45]

IodineExcessive iodine intake is a well-established environmental factor for triggering thyroid autoimmunity. Thyroid autoantibodies are found to be more prevalent in geographical areas with a higher dietary iodine levels. Several mechanisms by which iodine may promote thyroid autoimmunity have been proposed:

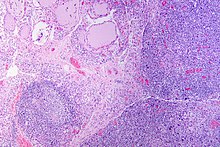

Data from the Danish Investigation of Iodine Intake and Thyroid Disease shows that within two cohorts (males, females) with moderate and mild iodine deficiency, the levels of both thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin antibodies are higher in females, and prevalence rates of both antibodies increase with age.[50] ComorbiditiesComorbid autoimmune diseases are a risk factor for developing Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and the opposite is also true.[3] Another thyroid disease closely associated with Hashimoto's thyroiditis is Graves' disease.[18] Autoimmune diseases affecting other organs most commonly associated with Hashimoto's thyroiditis include celiac disease, type 1 diabetes, vitiligo, alopecia,[51] Addison disease, Sjogren's syndrome, and rheumatoid arthritis[13][52] Autoimmune thyroiditis has also been seen in patients with autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes type 1 and 2.[18] OtherOther environmental factors include selenium deficiency,[8] infectious diseases such as hepatitis C, rubella, and possibly Covid-19,[53][54][55] toxins,[5] dietary factors,[18] radiation exposure,[5] and gut dysbiosis.[56] MechanismThe pathophysiology of autoimmune thyroiditis is not well understood.[5] However, once the disease is established, its core processes have been observed: Hashimoto's Thyroiditis is a T-lymphocyte mediated attack on the thyroid gland.[15] T helper 1 cells trigger macrophages and cytotoxic lymphocytes to destroy thyroid follicular cells, while T helper 2 cells stimulate the excessive production of B cells and plasma cells which generate antibodies against the thyroid antigens, leading to thyroiditis.[57] The three major antibodies are: Thyroid peroxidase Antibodies (TPOAb), Thyroglobulin Antibodies (TgAb), and Thyroid stimulating hormone receptor Antibodies (TRAb),[27] with TPOAb and TgAb being most commonly implicated in Hashimotos.[5] They are hypothesized to develop as a result of thyroid damage, where T-lymphocytes are sensitized to residual thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin, rather than as the initial cause of thyroid damage.[5] However, they may exacerbate further thyroid destruction by binding the complement system and triggering apoptosis of thyroid cells.[5] TPO antibody levels may correlate with the degree of lymphocyte infiltration of the thyroid.[58][59] Gross morphological changes within the thyroid are seen in the general enlargement, which is far more locally nodular and irregular than more diffuse patterns (such as that of hyperthyroidism). While the capsule is intact and the gland itself is still distinct from surrounding tissue, microscopic examination can provide a more revealing indication of the level of damage.[60] Hypothyroidism is caused by replacement of follicular cells with parenchymatous tissue.[57] Partial regeneration of the thyroid tissue can occur, but this has not been observed to normalise hormonal levels.[61][62] Pathology  Gross pathology of a thyroid with autoimmune thyroiditis may show an symmetrically enlarged thyroid.[5] It is often paler in color, in comparison to normal thyroid tissue which is reddish-brown.[5] Microscopic examination (histology) will show diffuse parenchymal infiltration by lymphocytes including plasma B-cells.[60] The lymphocytes are predominately T-lymphocytes with a representation of both CD4 positive and CD8 positive cells.[5] The plasma cells are polyclonal, with present germinal centers resembling the structure of a lymph node[5] (aka secondary lymphoid follicles, not to be confused with the normally present colloid-filled follicles that constitute the thyroid).[60] Atrophic colloid follicles are lined by Hürthle cells (cells with intensely eosinophilic and granular cytoplasm, which are a metaplasia of the normal cuboidal cells that line the thyroid follicles). Fibrous tissue may be found throughout the affected thyroid as well.[5] In late stages of the disease, the thyroid may be atrophic.[10] Severe thyroid atrophy presents often with denser fibrotic bands of collagen that remains within the confines of the thyroid capsule.[60] Generally, pathological findings of the thyroid are related to the amount of existing thyroid function - the more infiltration and fibrosis, the less likely a patient will have normal thyroid function.[5] A rare but serious complication is thyroid lymphoma, generally the B-cell type, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[27] Diagnosis TestsSome or all of the following tests may be performed, in any order: Physical examPhysicians will often start by assessing reported symptoms and performing a thorough physical exam, including a neck exam.[10] On gross examination, a hard goiter that is not painful to the touch often presents;[60] other symptoms seen with hypothyroidism, such as periorbital myxedema, depend on the current state of progression of the response, especially given the usually gradual development of clinically relevant hypothyroidism. Antithyroid antibodies testsTests for antibodies against thyroid peroxidase, thyroglobulin, and thyrotropin receptors can detect autoimmune processes against the thyroid. However, seronegative (without circulating autoantibodies) thyroiditis is also possible.[63] There may be circulating antibodies before the onset any symptoms.[10] Ultrasound An ultrasound may be useful in detecting Hashimoto thyroiditis, especially in those with seronegative thyroiditis,[15] or when patients have normal laboratory values but symptoms of autoimmune thyroiditis.[52] Key features detected in the ultrasound of a person with Hashimoto's thyroiditis include "echogenicity, heterogeneity, hypervascularity, and presence of small cysts."[15] Images obtained with ultrasound can evaluate the size of the thyroid, reveal the presence of nodules, or provide clues to the diagnosis of other thyroid conditions.[52] Nuclear medicineNuclear imaging showing thyroid uptake can also be helpful in diagnosing thyroid function, particularly differential diagnosis.[5] TSH plasma serum concentration testTo detect if the pituitary is stimulating an underperforming thyroid to produce more thyroid hormone. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) secretion from the anterior pituitary increases in response to decreased serum thyroid hormones. If elevated, it signifies hypothyroidism.[52] The elevation is usually a marked increase over the normal range.[13] TSH is the preferred initial test of thyroid function as it has a higher sensitivity to changes in thyroid status than free T4.[64] Biotin can cause this test to read "falsely low".[21] Time of day can affect the results of this test; TSH peaks early in the morning and slumps in the late afternoon to early evening,[65] with "a variation in TSH by a mean of between 0.95 mIU/mL to 2.0 mIU/mL".[66] Hypothyroidism is diagnosed more often in samples taken soon after waking.[67] T3 or T4 levels testTo detect a lack of thyroid hormones (hypothyroidism), or excess of thyroid hormones (hyperthyroidism). The two thyroid hormones are Thyroxine (T4) and Tri-iodothyronine (T3). T4 and T3 can be measured by their total amount, or free amount. As the free amount reflects the amount available to body tissues, the most treatment-relevant measures for thyroid disorders are Free T3 and Free T4.[68] Typically, Free T4 is the preferred test for hypothyroidism,[69] as Free T3 immunoassay tests are less reliable at detecting low levels of thyroid hormone,[70] and they are more susceptible to interference.[69] Free T4 levels will usually be lowered, but sometimes might be normal.[71] Immunoassay tests of Free T4 and Free T3 may overestimate concentrations, particularly at low thyroid hormone levels, which is why results are typically read in conjunction with TSH, a more sensitive measure.[68] LC-MSMS assays are rarer, but they are "highly specific, sensitive, precise, and can detect hormones found in low concentrations."[68] Muscle BiopsyMuscle biopsy is not necessary for diagnosis of myopathy due to hypothyroid muscle fibre changes, however it may reveal confirmatory features.[17] TreatmentThere is no cure for Hashimoto's Thyroiditis.[56][72] There is currently no known way to stop auto-immune lymphocytes infiltrating the thyroid[5] or to stimulate regeneration of thyroid tissue.[5] However, the condition can be managed.[56][72]  Managing hormone levels

Hypothyroidism caused by Hashimoto's thyroiditis is treated with thyroid hormone replacement agents such as levothyroxine (LT4), liothyronine (LT3), or desiccated thyroid extract (T4+T3). A tablet or liquid taken once a day generally keeps the thyroid hormone levels normal. In most cases, the treatment needs to be taken for the rest of the person's life. The standard of care is levothyroxine (LT4) therapy, which is an oral medication identical in molecular structure to endogenous thyroxine (T4).[21] Levothyroxine sodium has a sodium salt added to increase the gastrointestinal absorption of levothyroxine.[73] Levothyroxine has the benefits of a long half-life[23] leading to stable thyroid hormone levels,[74] ease of monitoring,[74] excellent safety[74][75] and efficacy record,[68] and usefulness in pregnancy as it can cross the fetal blood-brain barrier.[15] Levothyroxine dosing to normalise TSH is based on the amount of residual endogenous thyroid function and the patient’s weight, particularly lean body mass.[15] The dose can be adjusted based upon each patient, for example, the dose may be lowered for elderly patients or patients with certain cardiac conditions, but should be increased in pregnant patients.[10] It should be administered on a consistent schedule.[21] Levothyroxine may be dosed daily or weekly, however weekly dosing may be associated with higher TSH levels, elevated thyroid hormone levels, and transient "echocardiographic changes in some patients following 2-4 h of thyroxine intake".[76][77] Some patients elect combination therapy with both levothyroxine and liothyronine, which is identical in molecular structure to tri-iodothyronine (T3), however studies of combination therapy are limited,[5] and five meta-analyses/reviews "suggested no clear advantage of the combination therapy."[15] However, subgroup analysis found that patients who remain the most symptomatic while taking levothyroxine may benefit from therapy containing liothyronine.[15] There is a lack of evidence around the benefits, long-term effects and side effects of dessicated thyroid extract. It is no longer recommended for the treatment of hypothyroidism.[78] Side EffectsSide effects of thyroid replacement therapy are associated with "inadequate or excessive doses."[21] Symptoms to watch for include, but are not limited to, anxiety, tremor, weight loss, heat sensitivity, diarrhea, and shortness of breath. More worrisome symptoms include atrial fibrillation and bone density loss.[21] Long term over-treatment is associated with increased mortality and dementia.[22] MonitoringThyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) is the laboratory value of choice for monitoring response to treatment with levothyroxine.[71] When treatment is first initiated, TSH levels may be monitored as often as a frequency of every 6–8 weeks.[71] Each time the dose is adjusted, TSH levels may be measured at that frequency until the correct dose is determined.[71] Once titrated to a proper dose, TSH levels will be monitored yearly.[71] The target level for TSH is the subject of debate, with factors like age, sex, individual needs and special circumstances such as pregnancy being considered.[79] Recent studies suggest that adjusting therapy based on thyroid hormone levels (T4 and/or T3) may be important.[21] Monitoring liothyronine treatment or combination treatment can be challenging.[79][74][80] Liothyronine can suppress TSH to a greater extent than levothyroxine.[81] Short-acting Liothyronine's short half-life can result in large fluctuations of free T3[80] over the course of 24 hours.[82] Patients may have to adjust their dosage several times over the course of the disease. Endogenous thyroid hormone levels may fluctuate, particularly early in the disease.[83] Patients may sometimes develop hyperthyroidism, even after long-term treatment.[5] This can be due to a number of factors including acute attacks of destructive thyrotoxicosis (autoimmune attacks on the thyroid resulting in rises in thyroid hormone levels as thyroid hormones leak out of the damaged tissues).[20][5] This is usually followed by hypothyroidism.[5] Reverse T3Measuring reverse tri-iodothyronine (rT3) is often mentioned in the lay (non-medical) press as a possible marker to inform T4 or T3 therapy, "however, there is currently no evidence to support this application" as of 2023.[69] Although cited in the lay press as a possible competitor to T3, it is unlikely that rT3 causes hypothyroid symptoms by out-competing T3 for thyroid hormone receptors, as it has a binding affinity 200 times weaker.[84] It is also unlikely that rT3 causes poor T4 to T3 conversion; despite being demonstrated in vivo to have the potential to inhibit DIO-mediated T4 to T3 conversion, this is considered improbable at normal body hormone concentrations.[84] Persistent SymptomsMultiple studies have demonstrated persistent symptoms in Hashimotos patients with normal thyroid hormone levels (euthyroid)[21][79][15][23] and an estimated 10%-15% of patients treated with levothyroxine monotherapy are dissatisfied due to persistent symptoms of hypothyroidism.[85][22] Several different hypothesised causes are discussed in the medical literature:[86][23][15] Low tissue tri-iodothyronine (T3) hypothesisPeripheral tissue T4 to T3 conversion may be inadequate. Patients on LT4 monotherapy may have blood T3 levels low or below the normal range,[21][79] and/or may have local T3 deficiency in some tissues.[87] Although both molecules can have biological effects, thyroxine (T4) is considered the "storage form" of thyroid hormone, while tri-iodothyronine (T3) is considered the active form used by body tissues.[88][89] The body must convert thyroxine into tri-iodothyronine in order to have biological effects.[89] Tri-iodothyronine is produced primarily by conversion in the liver, kidney, skeletal muscle and pituitary gland.[90] Possible reasons for poor conversion include:

Patients with impaired conversion may be recommended combination therapy of both levothyroxine and liothyronine.[95][96] As standard immunoassay tests can overestimate blood T4 and T3 levels, Ultrafiltration LC-MSMS T4 and T3 tests may help to identify patients who would benefit from additional T3.[68] Inadequate markers hypothesisThere is ongoing debate about how to define euthyroidism and whether TSH is its best indicator.[85] TSH may be useful to detect poor thyroid output and may reflect the state of thyroid hormones in the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, but not the presence of hormones in other body tissues.[22][79][87] As a result, LT4 monotherapy may not result in a "truly biochemically euthyroid state."[23] Patients may express a preference for "low normal or below normal TSH values"[87] and/or T4 and T3 monitoring. The monitoring of other biomarkers that reflect the action of thyroid hormone on tissue levels has also been proposed.[15][97][22] As immunoassay Free T3 and Free T4 tests can overestimate levels, particularly at low thyroid hormone levels, hypothyroidism may be undertreated.[68] LC-MSMS tests may provide more reliable measures.[68] Extra-thyroidal effects of autoimmunity hypothesisIt is hypothesised that autoimmunity may play some role in euthyroid symptoms.[79][98][23] Hypothesised mechanisms include the proposal that TPO-antibody-producing lymphocytes may travel out of the thyroid to other tissue, creating symptoms and inflammation due to cross-reaction,[23][99] or "the inflammatory nature of [...] persistently increased circulating cytokine levels."[79] Multiple studies find that antibodies coincide with symptoms even in euthyroid patients,[5][23] and higher levels are associated with increased symptoms,[21] however "the found association does not prove a causality".[23] No treatment currently exists for Hashimotos autoimmunity, although observed wellbeing improvements after surgical thyroid removal are hypothesised to be due to removing the autoimmune stimulus.[15][99] Physical and psychosocial co-morbidities hypothesisIt is hypothesised that symptoms may not be due to Hashimotos or hypothyroidism, but some other "physical and psychosocial co-morbidities".[86][22] Other influences on thyroid hormone levelsZinc may increase free T3 levels.[100] A small pilot study found Ashwagandha Root may increase T3 and T4 levels, however, there's a lack of strong evidence of this benefit and Ashwagandha has a potential to cause adrenal insufficiency.[100] Improving wellbeingSome patients may perceive improved wellbeing while in thyrotoxicosis, however overtreatment has risks (known risks for levothyroxine and unknown risks for liothyronine).[22] One study demonstrated surgical thyroid removal may substantially improve fatigue and wellbeing,[79][5] see Surgery considerations. Reducing antibodiesIt is not established that reducing antithyroid antibodies in Hashimoto's has benefits.[98][15][101] A systematic review and meta-analysis of selenium trials found that while selenium reduces TPO antibodies, there was a lack of evidence of effects on "disease remission, progression, lowered levothyroxine dose or improved quality of life".[8] Selenium,[102][8] vitamin D,[103] and metformin[104] can reduce thyroid peroxidase antibodies. There is preliminary evidence that Levothyroxine,[105][106] Aloe Vera Juice[107] and Black Cumin Seed[108] may reduce thyroid peroxidase antibodies. Metformin can reduce thyroglobulin antibodies.[104] It is not established that a gluten-free diet can reduce antibodies when there is no comorbid coeliac disease.[109][100] Gluten free diets have been shown in several studies to reduce antibodies, and in other studies to have no effect, however there were significant confounding issues in these studies, including not ruling out comorbid coeliac disease.[109] One study found Surgical thyroid removal can substantially reduce anti-thyroid antibody levels,[79][5] see Surgery considerations. Surgery considerationsSurgery is not the initial treatment of choice for autoimmune disease, and uncomplicated Hashimoto's thyroiditis is not an indication for thyroidectomy.[5] Patients generally may discuss surgery with their doctor if they are experiencing significant pressure symptoms, or cosmetic concerns, or have nodules present on ultrasound.[5] One well-conducted study of patients with troublesome general symptoms and with anti-thyroperoxidase (anti-TPO) levels greater than 1000 IU/ml (normal <100 IU/ml) showed that total thyroidectomy caused the symptoms to resolve and median anti-thyroid peroxidase levels to reduce from 2232 to 152 IU/mL,[5][110] but post-operative complications were higher than expected:[79] infection (4.1%), permanent hypoparathyroidism (4.1%) and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury (5.5%).[86] OtherAs of 2022, there has been only one study of low-dose naltrexone in Hashimotos, which did not demonstrate efficacy, therefore nothing supports its use; Removing dairy products in those without lactose intolerance has not been found to be supported.[100] While soy isoflavones have the potential to theoretically affect T3 and T4 production, studies in those with sufficient iodine find no effect.[100] PrognosisOvert, symptomatic thyroid dysfunction is the most common complication, with about 5% of people with subclinical hypothyroidism and chronic autoimmune thyroiditis progressing to thyroid failure every year. Transient periods of thyrotoxicosis (over-activity of the thyroid) sometimes occur, and rarely the illness may progress to full hyperthyroid Graves' disease with active orbitopathy (bulging, inflamed eyes).[111] Rare cases of fibrous autoimmune thyroiditis present with severe shortness of breath and difficulty swallowing, resembling aggressive thyroid tumors, but such symptoms always improve with surgery or corticosteroid therapy. Although primary thyroid B-cell lymphoma affects fewer than one in 1000 persons, it is more likely to affect those with long-standing autoimmune thyroiditis,[111] as there is a 67- to 80-fold increased risk of developing primary thyroid lymphoma in patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis.[112] Myopathy as a result of muscle fibre changes due to thyroid hormone deficiency may take months[17] or years[113] of thyroid hormone treatment to resolve. Anti-thyroid antibodiesThyroid peroxidase antibodies typically (but not always) decline in patients treated with levothyroxine,[101] with decreases varying between 10% and 90% after a follow-up of 6 to 24 months.[114] One study of patients treated with levothyroxine observed that 35 out of 38 patients (92%) had declines in thyroid peroxidase antibody levels over five years, lowering by 70% on average. 6 of the 38 patients (16%) had thyroid peroxidase antibody levels return to normal.[114] ChildrenMany children diagnosed with Hashimoto's disease will experience the same progressive course of the disease that adults do.[115] However, of children who develop anti-thyroid antibodies and hypothyroidism, up to 50% are later observed to have normal antibodies and thyroid hormone levels.[5] One case of true remission has been observed in a 12-year-old girl. Her thyroid was observed via ultrasound to progress from early inflammation to severe end-stage Hashimoto's thyroiditis with hypothyroidism, and then return to "almost normal with only minimal features of inflammation" and euthyroidism.[116][117] EpidemiologyHashimoto's Disease is estimated to affect 2% of the world's population.[5][28] About 1.0 to 1.5 in 1000 people have this disease at any time.[60] SexAnyone may develop this disease, but it occurs between 8[21] and 15 times more often in women than in men. Some research suggests a connection to the role of the placenta as an explanation for the sex difference.[118] The difference in prevalence amongst genders is due to the effects of sex hormones.[18] High iodine consumptionAutoimmune thyroiditis has a higher prevalence in societies that have a higher intake of iodine in their diet, such as the United States and Japan, and among people who are genetically susceptible.[119] It is the most common cause of hypothyroidism in areas of sufficient iodine.[10] Also, the rate of lymphocytic infiltration increased in areas where the iodine intake was once low, but increased due to iodine supplementation.[27][120] Iodine deficiency disorder is combated using an increase in iodine in a person's diet. When a dramatic change occurs in a person's diet, they become more at-risk of developing hypothyroidism and other thyroid disorders. Treating iodine deficiency disorder with high salt intakes should be done carefully and cautiously as risk for Hashimoto's may increase.[120] Geographic influence of dietary trendsGeography plays a large role in which regions have access to diets with low or high iodine. Iodine levels in both water and salt should be heavily monitored in order to protect at-risk populations from developing hypothyroidism.[121] Geographic trends of hypothyroidism vary across the world as different places have different ways of defining disease and reporting cases. Populations that are spread out or defined poorly may skew data in unexpected ways.[28] North AmericaHashimoto's thyroiditis may affect up to 5% of the United States' population.[122] Hashimoto's thyroiditis disorder is thought to be the most common cause of primary hypothyroidism in North America.[60] AgeIt has been shown that the prevalence of positive tests for thyroid antibodies increases with age, "with a frequency as high as 33 percent in women 70 years old or older."[27] Hashimoto's thyroiditis can occur at any age, including children,[119] but more commonly appears in middle age, particularly for men.[123] Incidence peaks in the fifth decade of life, but patients are usually diagnosed between age 30–50.[52][122] The highest prevalence from one study was found in the elderly members of the community.[124] RaceThe prevalence of Hashimoto's varies geographically. The highest rate is in Africa, and the lowest in Asia.[9] In the US, the African-American population experiences it less commonly but has greater associated mortality.[125] Autoimmune diseasesThose that already have an autoimmune disease are at greater risk of developing Hashimoto's as the diseases generally coexist with each other.[28] See Causes > Comorbidities, above. Secular trendsThe secular trends of hypothyroidism reveal how the disease has changed over the course of time given changes in technology and treatment options. Even though ultrasound technology and treatment options have improved, the incidence of hypothyroidism has increased according to data focused on the US and Europe. Between 1993 and 2001, per 1000 women, the disease was found varying between 3.9 and 4.89. Between 1994 and 2001, per 1000 men, the disease increased from 0.65 to 1.01.[124] Changes in the definition of hypothyroidism and treatment options modify the incidence and prevalence of the disease overall. Treatment using levothyroxine is individualized, and therefore allows the disease to be more manageable with time but does not work as a cure for the disease.[28] HistoryAlso known as Hashimoto's disease, Hashimoto's thyroiditis is named after Japanese physician Hakaru Hashimoto (1881−1934) of the medical school at Kyushu University,[126] who first described the symptoms of persons with struma lymphomatosa, an intense infiltration of lymphocytes within the thyroid, in 1912 in the German journal called Archiv für Klinische Chirurgie.[4][127] This paper was made up of 30 pages and 5 illustrations all describing the histological changes in the thyroid tissue. Furthermore, all results in his first study were collected from four women. These results explained the pathological characteristics observed in these women especially the infiltration of lymphocyte and plasma cells as well as the formation of lymphoid follicles with germinal centers, fibrosis, degenerated thyroid epithelial cells and leukocytes in the lumen.[4] He described these traits to be histologically similar to those of Mikulic's disease. As mentioned above, once he discovered these traits in this new disease, he named the disease struma lymphomatosa. This disease emphasized the lymphocyte infiltration and formation of the lymphoid follicles with germinal centers, neither of which had ever been previously reported.[4] Despite Dr. Hashimoto's discovery and publication, the disease was not recognized as distinct from Reidel's thyroiditis, which was a common disease at that time in Europe. Although many other articles were reported and published by other researchers, Hashimoto's struma lymphomatosa was only recognized as an early phase of Reidel's thyroiditis in the early 1900s. It was not until 1931 that the disease was recognized as a disease in its own right, when researchers Allen Graham et al. from Cleveland reported its symptoms and presentation in the same detailed manner as Hashimoto.[4] In 1956, Drs. Rose and Witebsky were able to demonstrate how immunization of certain rodents with extracts of other rodents' thyroid resembled the disease Hakaru and other researchers were trying to describe.[4] These doctors were also able to describe anti-thyroglobulin antibodies in blood serum samples from these same animals.[4] Later on in the same year, researchers from the Middlesex Hospital in London were able to perform human experiments on patients who presented with similar symptoms. They purified anti-thyroglobulin antibody from their serum and were able to conclude that these sick patients had an immunological reaction to human thyroglobulin.[4] From this data, it was proposed that Hashimoto's struma could be an autoimmune disease of the thyroid gland. "Following these discoveries, the concept of organ-specific autoimmune disease was established and HT recognized as one such disease."[4] Following this recognition, the same researchers from Middlesex Hospital published an article in 1962 in The Lancet that included a portrait of Hakaru Hashimoto.[4] The disease became more well known from that moment, and Hashimoto's disease started to appear more frequently in textbooks.[128] PregnancyConceptionIt is recommended that hypothyroidism be treated with levothyoxine before conception, to prevent adverse effects on the course of the pregnancy and on the development of the child.[15] In IVF, embryo transfer is improved when hypothyroidism is treated.[129] PregnancyThe Endocrine Society recommends screening in pregnant women who are considered high-risk for thyroid autoimmune disease.[130] Universal screening for thyroid diseases during pregnancy is controversial, however, one study "supports the potential benefit of universal screening".[131] Pregnant women may have antithyroid antibodies (5%–14% of pregnancies[15]), poor thyroid function resulting in hypothyroidism, or both. Each is associated with risks.[15] Anti-thyroid antibodies in pregnancyThe presence of Thyroid peroxidase antibodies at the outset of pregnancy are associated with a greater risk to the mother of hypothyroidism and thyroid impairment in the first year after delivery.[132] The presence of antibodies is also associated with "a 2 to 4-fold increase in the risk of recurrent miscarriages, and 2 to 3-fold increased risk of preterm birth", however the reason why is unclear. Thyroid peroxidase antibodies are speculated to indicate other autoimmune processes against the placental-fetal unit.[15] Levothyroxine treatment in euthyroid women with thyroid autoimmunity does not significantly impact the relative risk of miscarriage and preterm delivery, or outcomes with live birth. "Therefore, no strong recommendations regarding the therapy in such scenarios could be made, but consideration on a case-by-case basis might be implemented."[15] Hypothyroidism in pregnancy.Women who have low thyroid function that has not been stabilized are at greater risk of complications for both parent and child. Risks to the mother include gestational hypertension including preeclampsia and eclampsia, gestational diabetes, placental abruption, and postpartum hemorrhage.[15] Risks to the infant include miscarriage, preterm delivery, low birth weight, neonatal respiratory distress, hydrocephalus, hypospadias, fetal death, infant intensive care unit admission, and neurodevelopmental delays (lower child IQ, language delay or global developmental delay).[131][129][15] Successful pregnancy outcomes are improved when hypothyroidism is treated.[129] Levothyroxine treatment may be considered at lower TSH levels in pregnancy than in standard treatment.[15] Liothyronine does not cross the fetal blood-brain barrier, so liothyronine (T3) only or liothyronine + levothyroxine (T3 + T4) therapy is not indicated in pregnancy.[15] Close cooperation between the endocrinologist and obstetrician benefits the woman and the infant.[131][133][134] Immune changes during pregnancyHormonal changes and trophoblast expression of key immunomodulatory molecules lead to immunosuppression and fetal tolerance. The main players in regulation of the immune response are Tregs. Both cell-mediated and humoral immune responses are attenuated, resulting in immune tolerance and suppression of autoimmunity. It has been reported that during pregnancy, levels of thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin antibodies decrease.[135] PostpartumThyroid peroxidase antibodies testing is recommended for women who have ever been pregnant regardless of pregnancy outcome. "[P]revious pregnancy plays a major role in development of autoimmune overt hypothyroidism in premenopausal women, and the number of previous pregnancies should be taken into account when evaluating the risk of hypothyroidism in a young women [sic]."[44] Postpartum thyroiditis can occur in women with Hashimoto's.[5] In healthy women, Postpartum thyroiditis can occur up to 1 year after delivery and should be differentiated from Hashimoto's thyroiditis as it is treated differently.[136] After giving birth, Tregs rapidly decrease and immune responses are re-established. It may lead to the occurrence or aggravation of autoimmune thyroid disease.[135] In up to 50% of females with thyroid peroxidase antibodies in the early pregnancy, thyroid autoimmunity in the postpartum period exacerbates in the form of postpartum thyroiditis.[137] Higher secretion of IFN-γ and IL-4, and lower plasma cortisol concentration during pregnancy has been reported in females with postpartum thyroiditis than in healthy females. It indicates that weaker immunosuppression during pregnancy could contribute to the postpartum thyroid dysfunction.[138] Fetal microchimerismSeveral years after the delivery, the chimeric male cells can be detected in the maternal peripheral blood, thyroid, lung, skin, or lymph nodes. The fetal immune cells in the maternal thyroid gland may become activated and act as a trigger that may initiate or exaggerate the autoimmune thyroid disease. In Hashimoto's disease patients, fetal microchimeric cells were detected in thyroid in significantly higher numbers than in healthy females.[139] Other animalsHashimoto's disease is known to occur in chickens, rats, mice, dogs, and marmosets, but Graves' disease does not.[140] PseudosciencePseudoscientific claims and "rogue practitioners" pose increasing risks to patients.[141]

See alsoReferences

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||