|

Pericardial effusion

A pericardial effusion is an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the pericardial cavity. The pericardium is a two-part membrane surrounding the heart: the outer fibrous connective membrane and an inner two-layered serous membrane. The two layers of the serous membrane enclose the pericardial cavity (the potential space) between them.[1] This pericardial space contains a small amount of pericardial fluid, normally 15-50 mL in volume.[2] The pericardium, specifically the pericardial fluid provides lubrication, maintains the anatomic position of the heart in the chest (levocardia), and also serves as a barrier to protect the heart from infection and inflammation in adjacent tissues and organs.[3][4] By definition, a pericardial effusion occurs when the volume of fluid in the cavity exceeds the normal limit.[5] If large enough, it can compress the heart, causing cardiac tamponade and obstructive shock.[6] Some of the presenting symptoms are shortness of breath, chest pressure/pain, and malaise. Important etiologies of pericardial effusions are inflammatory and infectious (pericarditis), neoplastic, traumatic, and metabolic causes. Echocardiogram, CT and MRI are the most common methods of diagnosis, although chest X-ray and EKG are also often performed. Pericardiocentesis may be diagnostic as well as therapeutic (form of treatment). Signs and symptomsPericardial effusion presentation varies from person to person depending on the size, acuity and underlying cause of the effusion.[5] Some people may be asymptomatic and the effusion may be an incidental finding on an examination.[1] Others with larger effusions may present with chest pressure or pain, dyspnea, shortness of breath, and malaise (a general feeling of discomfort or illness). Yet others with cardiac tamponade, a life-threatening complication, may present with dyspnea, low blood pressure, weakness, restlessness, hyperventilation (rapid breathing), discomfort with lying flat, dizziness, syncope or even loss of consciousness.[2] This causes a type of shock, called obstructive shock, which can lead to organ damage.[6] Non-cardiac symptoms may also present due to the enlarging pericardial effusion compressing nearby structures. Some examples are nausea and abdominal fullness, dysphagia and hiccups, due to compression of stomach, esophagus, and phrenic nerve respectively.[4] CausesAny process that leads to injury or inflammation of the pericardium or inhibits appropriate lymphatic drainage of the fluid from the pericardial cavity leads to fluid accumulation.[4] Pericardial effusions can be found in all populations worldwide but the predominant etiology has changed over time, varying depending on the age, location, and comorbidities of the population in question.[2] Out of all the numerous causes of pericardial effusion, some of the leading causes are inflammatory, infectious, neoplastic and traumatic. These causes can be categorized into various classes, but an easy way to understand them is dividing them into inflammatory versus non-inflammatory. [citation needed]  Inflammatory

Non-Inflammatory

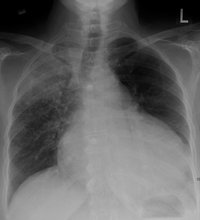

Pathophysiology How much fluid is stored in the pericardial sac at one particular time is based on the balance between production and reabsorption. Studies have shown that much of the fluid that accumulates in the pericardial sac is from plasma filtration of the epicardial capillaries and a small amount from the myocardium, while the fluid that is drained is mostly via the parietal lymphatic capillaries.[3] Pericardial effusion usually results from a disturbed equilibrium between these two processes or from a structural abnormality that allows excess fluid to enter the pericardial cavity.[3] Because of the limited amount of anatomic space in the pericardial cavity and the limited elasticity of the pericardium, fluid accumulation beyond the normal amount leads to an increased intrapericardial pressure which can negatively affect heart function. [citation needed] A pericardial effusion with enough pressure to adversely affect heart function is called cardiac tamponade.[1] Pericardial effusions can cause cardiac tamponade in acute settings with fluid as little as 150mL. In chronic settings, however, fluid can accumulate anywhere up to 2L before an effusion causes cardiac tamponade. The reason behind this is the elasticity of the pericardium. When fluid fills the cavity rapidly, the pericardium cannot stretch rapidly, but in chronic effusions, the gradual fluid collection provides the pericardium enough time to accommodate and stretch with the increasing fluid levels.[2] DiagnosisPatients with pericardial effusion may have unremarkable physical exams but often present with tachycardia, distant heart sounds and tachypnea.[5] A physical finding specific to pericardial effusion is dullness to percussion, bronchial breath sounds and egophony over the inferior angle of the left scapula. This phenomenon is known as Ewart's sign and is due to compression of the left lung base.[2] Patients with concern for cardiac tamponade may present with abnormal vitals and what's classically known as the Beck's triad, which consists of hypotension (low blood pressure), jugular venous distension and distant heart sounds. Though these are the classical findings; all three occur simultaneously in only a minority of patients.[1] Patients presenting with cardiac tamponade may also be evaluated for pulsus paradoxus. Pulsus paradoxus is a phenomenon in which systolic blood pressure drops by 10 mmHg or more during inspiration. In cardiac tamponade, the pressure within the pericardium is significantly higher, hence decreasing the compliance of the chambers (the capacity to expand/ conform to volume changes). During inspiration, right ventricle filling in increased, which causes the Interventricular septum to bulge into the left ventricle, hence leading to reduced left ventricular filling and consequently reduced stroke volume and low systolic blood pressure.[2] Exams  Some patients with pericardial effusions may present with no symptoms and the diagnosis can be an incidental finding due to imaging of other illnesses. Patients who present with dyspnea or chest pain have a broad differential diagnosis and it may be necessary to rule out other causes like myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, acute pericarditis, pneumonia, and esophageal rupture.[2] Initial tests include electrocardiography (ECG) and chest x-ray. Chest x-ray: is non-specific and may not help identify a pericardial effusion but a very large, chronic effusion can present as "water-bottle sign" on an x-ray, which occurs when the cardiopericardial silhouette is enlarged and assumes the shape of a flask or water bottle.[2] Chest radiograph is also helpful in ruling out pneumothorax, pneumonia, and esophageal rupture. [citation needed] ECG: may present with sinus tachycardia, low voltage QRS as well as electrical alternans.[2] Due to the fluid accumulation around the heart, the heart is further away from the chest leads, which leads to the low voltage QRS. Electrical alternans signifies the up-and-down change of the QRS amplitude with every beat due to the heart swinging in the fluid (as displayed in the ultrasound image in the introduction) .[1] These three findings together should raise suspicion for impending hemodynamic instability associated with cardiac tamponade. [citation needed] Echocardiogram (ultrasound): when pericardial effusion is suspected, echocardiography usually confirms the diagnosis and allows assessment of the size, location and signs of hemodynamic instability.[4] A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) is usually sufficient to evaluate pericardial effusion and it may also help distinguish pericardial effusion from pleural effusion and MI. Most pericardial effusions appear as an anechoic area (black or without an echo) between the visceral and the parietal membrane.[1] Complex or malignant effusions are more heterogeneous in appearance, meaning they may have variations in echo on ultrasound.[5] TTE can also differentiate pericardial effusion based on the size. Although it's difficult to define size classifications because they vary with institutions, most commonly they are as follows: small <10, moderate 10–20, large >20.[5] An echocardiogram is urgently needed for evaluation when there is concern for hemodynamic compromise, a rapidly developing effusion or history of recent cardiac surgery/procedures.[1] Cardiac CT and MRI scans: cross-sectional imaging with computed tomography (CT) can help localize and quantify the effusion, especially in a loculated effusion (an effusion contained to one area).[12] CT imaging also helps assess for pericardial pathology (pericardial thickening, constrictive pericarditis, malignancy-associated pericarditis).[1] Whereas cardiac MRI is reserved for patients with poor echocardiogram findings and for assessing pericardial inflammation, especially for patients with continued inflammation despite treatment.[5] CT and MRI imaging can also be used for continued follow up on patients. [citation needed] Pericardiocentesis: is a procedure in which fluid is aspirated from the pericardial cavity with a needle and catheter. This procedure can be used to analyze the fluid but more importantly can also provide symptomatic relief, especially in patients with hemodynamic compromise. Pericardiocentesis is usually guided by an echocardiogram to determine the exact location of the effusion and the optimal location of puncture site to minimize risk of complications.[5] After the procedure, the aspirated fluid is analyzed for gross appearance (color, consistency, bloody), cell count, and concentration of glucose, protein, and other cellular components (for example lactate dehydrogenase).[13] Fluid may be also sent for gram stain, acid fast stain, or culture if high suspicion of infectious cause.[1] Bloody fluids may also be evaluated for malignant cells.[13] Fluid analysis may result in:

TreatmentTreatment depends on the underlying cause and the severity of the heart impairment.[1] For example, pericardial effusion from autoimmune etiologies may benefit from anti-inflammatory medications. Pericardial effusion due to a viral infection usually resolves within a few weeks without any treatment.[8] Small pericardial effusions without any symptoms don't require treatment and may be watched with serial ultrasounds.[2] If the effusion is compromising heart function and causing cardiac tamponade, it will need to be drained.[1] Fluid can be drained via needle pericardiocentesis as discussed above or surgical procedures, such as a pericardial window.[2] The intervention used depends on the cause of pericardial effusion and the clinical status of the patient.[citation needed] Pericardiocentesis is the choice of treatment in unstable patients: it can be performed at the bedside and in a timely manner.[4] A drainage tube is often left in place for 24 hours or more for assessment of re-accumulation of fluid and also for continued drainage.[4] Patients with cardiac tamponade are also given IV fluids and/or vasopressors to increase systemic blood pressure and cardiac output.[1] But in localized or malignant effusions, surgical drainage may be required instead. This is most often done by cutting through the pericardium and creating a pericardial window[1] This window provides a path for the fluid to be drained directly into the chest cavity, which prevents future development of cardiac tamponade. In localized effusions, it might be difficult to get safe access for pericardiocentesis, hence a surgical procedure is preferred. In case of malignant effusions, the high likelihood of recurrence of fluid accumulation is the main reason for a surgical procedure.[4] Pericardiocentesis is not preferred for chronic treatment options due to risk of infection.[citation needed] References

External links |

||||||||