|

HMS Magnanime (1748)

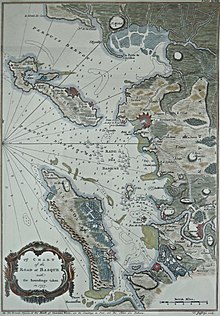

Le Magnanime [ma.ɲa.nim] was originally a 74-gun ship of the line of the French Navy launched in 1744 at Rochefort. Captured on 12 January 1748, she was taken into Royal Navy service as the third rate HMS Magnanime. She played a major part in the 1757 Rochefort expedition, helping to silence the batteries on the Isle of Aix, and served at the Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759 under Lord Howe, where she forced the surrender of the French 74-gun Héros. Following a survey in 1770, she was deemed unseaworthy and was broken up in 1775. ConstructionLe Magnanime was built between 1741 and 1745 in the port of Rochefort on the Charente estuary, France, and was designed by the renowned shipwright Blaise Geslain. She was 165 French feet in length (1531⁄2 French feet on the keel), 441⁄2 French feet in breadth and 22 French feet in depth in hold;[1] she measured 1,600 tons (2,900 tons displacement). As remeasured by the British following her capture, she was 173 feet 7 inches (52.91 m) along her gundeck with a 49 feet 4.5 inches (15.050 m) beam, and with a depth in the hold of 21 feet 7 inches (6.58 m), she had a capacity of just over 1,823 tons BM. When first fitted out by the British, Magnanime carried twenty-eight 32 pounders (15 kg) cannon on her lower deck (replacing the French 36-livre guns she had originally carried), thirty 18 pounders (8.2 kg) on her upper deck (replacing her French 18-livre guns), and sixteen 9 pounders (4.1 kg) guns (replacing her French 8-livre guns) – ten on her quarterdeck and six on her forecastle.[2][3] CaptureIn January 1748, Le Magnanime left Brest for the East Indies. She was partially dismasted in a storm off the coast of Ushant and while limping back to Brest, she was spotted by a British fleet under Edward Hawke. Le Magnanime was chased and engaged by HMS Nottingham and HMS Portland, and was forced to strike with 45 members of her crew killed and 105 injured. Nottingham had 16 killed and 18 wounded while Portland, catching up and joining the fight an hour later, had only 4 wounded.[4][a] Royal Navy serviceMagnanime was purchased by the Navy Board in July 1749 and, after an extensive refit, went to sea in 1756 under the command of Captain Wittewronge Taylor. She served as Rear-Admiral Savage Mostyn's flagship, part of the Channel Fleet commanded by Vice Admirals Edward Boscawen and later, Charles Knowles.[2] Rochefort Expedition While in Admiral Hawke's fleet, under Captain Richard Howe, Magnanime took part in the 1757 Raid on Rochefort, one of a series of raids designed to draw French troops away from the German front.[2][6] The plan to take Rochefort itself was later abandoned but Île d'Aix was captured and in the preceding battle, it was Magnanime's guns that bombarded the island's fort into submission.[7] The British fleet began its final approach to Basque Roads on 19 September 1757, Île-d'Aix lying some way beyond at the mouth of the Charente estuary.[8] The island was extremely important to the port of Rochefort because ships of the line were required to load and unload supplies and armaments there, being unable to navigate the shallow river fully laden.[9] It was expected therefore to be heavily defended. Although, as Hawke was later to discover, a couple of third rates would be sufficient for the task.[9] Hawke had formed an advanced squadron, under Sir Charles Knowles, comprising Magnanime, Barfleur, Neptune, Torbay and Royal William, and at around noon he sent these ships on ahead.[9] Just after 14:00, as they were approaching the Antioch Passage, between Île d'Oléron and Île de Ré, a French two-decker was sighted, and Magnanime and two other vessels were ordered to pursue.[8] The squadron was now without a competent pilot, who was aboard Magnanime, and the fleet, Hawke having by this time caught up, had to wait until the three ships returned the following afternoon.[10] By this time the wind had dropped and the British were forced to anchor. The lack of wind caused further delays and it was not until the fifth attempt that the British finally managed to enter the bay.[11] On the morning of 23 September, at around 10:00, Knowles' squadron, with Magnanime in the lead, was sent to silence the batteries on Île de Aix. Howe came within range of the fort at noon but held his fire for a further hour until he had brought Magnanime up within 40 yards (37 m). Shortly after the second ship, Barfleur arrived, the fort surrendered.[12]  Quiberon BayIn 1758, Magnanime was in Admiral George Anson's fleet under the temporary command of Captain Jervis Porter before rejoining Hawke's fleet under Lord Howe once more.[2] In 1759 Hawke was charged with blockading the French coast but a storm had forced him off his station, allowing the French fleet, under the Comte de Conflans, to break out of Brest on 14 November.[13] On hearing the news, Hawke immediately set off in pursuit. Conflans had slowed on the night of the 19th in order to arrive at Quiberon at dawn, and to investigate a small squadron of ships under Admiral Robert Duff, 20 miles (32 km) off Belleisle. At this point Hawke's fleet appeared on the horizon.[14] Magnanime and two frigates had been ordered ahead and were the first ships to spot the French at around 8:30.[15] Conflans was faced with the decision to stand and fight in rough seas and unfavourable winds, or to attempt to reach the hazardous waters around Quiberon Bay before nightfall.[16] He chose the latter and Hawke gave the signal for 'line abreast'.[17] The French fleet entered the bay at around 14:30 and, despite the fading light, the British fleet followed with Magnanime in the van.[18][19]  The British van was already starting to overhaul the French and, around this time, the first shots were being exchanged. Magnanime's guns were not discharged however, Howe wanted to reach the centre of the enemy's fleet before firing.[18] Hawke's ship, HMS Royal George, entered the bay at around 16:00, by which time the French 80 gun Formidable had already surrendered to HMS Resolution.[20] Magnanime forced the 74-gun Héros to strike her colours, but was unable to take possession of the ship, which later ran aground.[21] In all six French battleships were wrecked or destroyed with one, Formidable, captured.[22] The rest of the French fleet dispersed with many jettisoning guns and supplies to escape over the shoals.[23] The British lost two ships.[22] Later careerIn July 1760, Howe was replaced as captain of Magnanime by Captain Robert Hughes. This was a temporary command however and Hughes was replaced by Captain Charles Saxton early in 1762 where she served as flagship to Commodore J. Cerrit in the Basque Roads.[2][24] Magnanime spent the summer of 1762 under Captain John Montagu, again in a fleet commanded by Edward Hawke but by the autumn of that year she was in Charles Hardy's fleet. She was surveyed by the Navy Board in 1763 and again in 1770 when she was considered unseaworthy. She was not repaired and was broken up in April 1775, at Plymouth.[2] Notes

References

Bibliography

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia