|

Gravesend Blockhouse

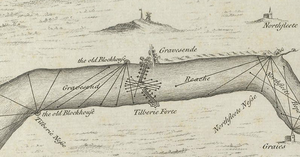

Gravesend Blockhouse was an artillery fortification constructed as part of Henry VIII's Device plan of 1539, in response to fears of an imminent invasion of England by European countries. It was built at Gravesend in Kent at a strategic point along the River Thames and was operational by 1540. A two-storey, D-shaped building built from brick and stone, it had a circular bastion overlooking the river and gun platforms extending out to the east and west. It functioned in conjunction with Tilbury Fort on the other side of the river, and was repaired in 1588 to deal with the threat of Spanish invasion, and again in 1667 when the Dutch navy raided the Thames. A 1778 report recommended alterations to the blockhouse and its defences, leading to the remodelling of the gun platforms and the construction of the new, larger New Tavern Fort alongside it. In the 1830s the government decided to rely entirely on the newer fort and the old blockhouse was demolished in 1844. Its remains were uncovered in archaeological excavations between 1975 and 1976. 16th centuryBackgroundGravesend Blockhouse was built as a consequence of international tensions between England, France and the Holy Roman Empire in the final years of the reign of King Henry VIII. Traditionally the Crown had left coastal defences to the local lords and communities, only taking a modest role in building and maintaining fortifications, and while France and the Empire remained in conflict with one another, maritime raids were common but an actual invasion of England seemed unlikely.[1] Modest defences, based around simple blockhouses and towers, existed in the south-west and along the Sussex coast, with a few more impressive works in the north of England, but in general the fortifications were very limited in scale.[2] In 1533, Henry then broke with Pope Paul III in order to annul the long-standing marriage to his wife, Catherine of Aragon and remarry.[3] Catherine was the aunt of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, and he took the annulment as a personal insult.[4] This resulted in France and the Empire declaring an alliance against Henry in 1538, and the Pope encouraging the two countries to attack England.[5] An invasion of England now appeared certain.[6] Device of 1539Henry issued an order, called a "device", in 1539, giving instructions for the "defence of the realm in time of invasion" and the construction of forts along the English coastline.[7] Under this programme of work the River Thames was protected with a mutually reinforcing network of blockhouses at Gravesend, Milton, and Higham on the south side of the river, and Tilbury and East Tilbury on the opposite bank.[8] The fortifications were strategically placed. London and the newly constructed royal dockyards of Deptford and Woolwich were vulnerable to seaborne attacks arriving up the Thames estuary, which was then a major maritime route, with 80 percent of England's exports passing through it.[9] The village of Milton and the adjacent town of Gravesend, only 500 metres (1,600 ft) apart, formed a particularly important communications point along the river.[10] They were the centre for the "Long Ferry" traffic of passengers into the capital, and for the "Cross Ferry" over the river to Tilbury, resulting in the local riverbank becoming lined with wharfs.[11] This was also the first point that an invasion force would be able to easily disembark along the Thames, as before this point the mudflats along the sides of the estuary would have made landings difficult.[12] Construction Gravesend Blockhouse was designed by the Clerk of the King's Works, James Nedeham, and the Master of Ordnance, Christopher Morice, with Robert Lorde serving as the paymaster for the project and Lionel Martin, John Ganyn and Mr Travers acting as the local overseers.[13] The Crown bought the land for the fort, along with the space for Gravesend Blockhouse, from William Burston for £66; it is uncertain how much the building work cost, but earlier estimates in 1539 had suggested that it would cost £211 to build such a blockhouse, including the 150,000 bricks and quantities of stone, chalk, lime, timber and labour that would be needed.[14][a] The work was quickly completed, and by 1540 the blockhouse was fully operational.[13] It was approximately 28 by 21 metres (92 by 69 ft) in size, two storeys tall, forming a D-shape, with a circular bastion at the front, extending into the Thames; another circular bastion jutted out from the side of the fort.[16] The bulk of the building was made of brick, faced with ashlar stone, with external walls 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) thick.[17] Two walls ran alongside either side of the blockhouse, parallel with the river, forming part of the adjacent platforms for mounting additional guns; in 1600, the east platform was described as being 100 feet (30 m) long and 14 feet (4.3 m) wide.[18] The rear of the blockhouse was overlooked by higher ground and would have been hard to defend.[19] The fort was initially commanded by Captain James Crane, with a garrison of ten men, including his second in command, a porter, six gunners and two soldiers.[20] As time went on, not all of the gunners worked full-time at the fort, some living and working in the town itself.[20] It is uncertain how many artillery pieces the blockhouse was initially equipped with, although it is known that the five blockhouses along the Thames had 108 brass and iron guns in total between them in 1540.[21] Use In 1553, orders were issued for the artillery pieces to be removed from Gravesend Blockhouse and taken to the Tower of London, although the historian Victor Smith casts doubt on whether this was actually carried out.[22] In 1588, however, there was a renewed threat of invasion, this time from Spain; the Spanish Armada sailed from A Coruña, while a separate invasion force was prepared in Flanders, threatening London; Rober Dudley, the Earl of Leicester was put in charge of the defences along the Thames.[19] When Dudley inspected the blockhouse, Gravesend was found to be in poor condition.[19] The gun platforms were unable to bear the weight of cannons, and the defences needed additional artillery and gunpowder; the permanent garrison by now only comprised five gunners.[19] One estimate that summer suggested that 1,000 feet (300 m) of structural timber, 300 iron spikes and 10 cartloads of smaller pieces of timber were needed for the repairs.[23] Plans were made to seal off the river with a chain or a boom stretching between the blockhouse and Tilbury Fort on the other bank, which was eventually accomplished at a cost of £305.[24][a] Further work was carried out on the defences, possibly including raising earthworks and establishing watch-houses.[23] Fears of an invasion persisted for many years afterwards and in 1598 Charles Howard, the Lord High Admiral, expressed his concerns about the effectiveness of the Gravesend Blockhouse in protecting the Thames.[23] 17th century A 1600 survey showed 10 pieces of artillery to be ineffective, while the gun platforms on either side of the fort were in bad condition and 2,828 feet (862 m) of planking, 650 joists and over 19 cartloads of other timber was needed for the repairs.[25] Little investment was forthcoming under James I or Charles I and by 1630 the garrison's pay was in arrears, with the fort was in need of repairs estimated at £1,248.[26][b] In 1631 the blockhouse was equipped with two brass demi-culverins and sakers, and an iron culverin, six demi-culverins, four sakers and one minion; the brass guns, which were needed for naval units, were exchanged for iron weapons in 1635.[28] In 1642 civil war broke out between the supporters of King Charles I and those of Parliament. Gravesend was controlled by Parliament, who placed it under the command of a military governor who oversaw both this fort and Tilbury, and was used to control traffic entering London and to search for spies.[29] Charles II regained the throne in 1660 and was petitioned by several royalists who claimed that they should be restored to the command of the blockhouse; William Leonard was ultimately successful.[30] The defences were repaired and may have been occasionally used by the King as a banqueting hall.[30] The Dutch fleet raided up the Thames in June 1667, but did not approach Gravesend Blockhouse due to the threat posed by its guns.[31] The fort, under the command of Sir John Griffith, was in reality not well prepared for war.[32] £400 was spent on upgrading the blockhouse, artillery was sent from the Tower of London to reinforce the local guns and four infantry companies were detached to guard the site.[30][b] The risk of attack ended with the signing of the Peace of Breda that July, and the blockhouse did not see action.[32] Shortly after the Dutch raids, Sir John was removed from his post for apparently demanding payments from ships passing by the blockhouse, a complaint which was repeated in later years under subsequent captains.[32] 18th–19th centuries By the start of the 18th century a complex of building had grown up around the original blockhouse, which now had a pier, a dock and two wharfs alongside it, and a large house built by the King's brother, James the Duke of York, after his return to England, as well as the two lines of approximately 20 guns stretching on either side along the river; it had a garrison of a sergeant, 20 soldiers and a gunner on loan from Tilbury Fort.[33] The blockhouse itself was no longer used to mount guns but instead acted as the magazine for the wider fortification, being able to store 2,500 barrels of gunpowder.[34] Under the terms of the Peace of Utrecht in 1713, the number of artillery pieces was reduced to ten, and a survey in 1766 reported that Gravesend was in good condition and equipped with ten 9 lb guns.[35] Amid rising concerns over the threat of a French invasion, Sir Thomas Page surveyed the blockhouse in 1778 and concluded that its guns were too closely packed together and that they could not easily fire down-river, proposing that a larger fort be built along the Thames to the east to rectify this problem.[36] New Tavern Fort was constructed shortly afterwards and the eastern Gravesend Blockhouse gun platform was redesigned and extended as part of the work.[37] Two volunteer militia companies were established in 1794 and 1797 to support the blockhouse and in 1805 it was equipped with 19 32 lb guns.[38] Concerns continued to be raised that the blockhouse's guns could not fire downriver and by the 1830s it had been decided to focus investment on the New Tavern and Tilbury forts.[38] The blockhouse itself fell out of use as a magazine in 1834, being briefly used as a government store, and the adjacent gun platforms were sold off in 1835.[38] The blockhouse building was subsequently demolished in 1844.[39] 20th–21st centuriesThe site of the former Gravesend Blockhouse was excavated in 1975 and 1976 by the Kent Archaeological Society, uncovering parts of the original building.[40] The site, which lies in the grounds of the Clarendon Royal Hotel, was protected under UK law as a scheduled monument in 1979.[41] Notes

References

Bibliography

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia