|

Grand Lodge of All England

The Grand Lodge of All England Meeting since Time Immemorial in the City of York was a body of Freemasons which existed intermittently during the Eighteenth Century, mainly based in the City of York. It does not appear to have been a regulatory body in the usual manner of a masonic Grand Lodge, and as such is seen as a "Mother Lodge" like Kilwinning in Scotland. It met to create Freemasons, and as such enabled the foundation of new lodges. For much of its career, it was the only lodge in its own jurisdiction, but even with dependent lodges it continued to function mainly as an ordinary lodge of Freemasons. Having existed since at least 1705 as the Ancient Society of Freemasons in the City of York, it was in 1725, possibly in response to the expansion of the new Grand Lodge in London, that they styled themselves the Grand Lodge of All England Meeting at York. Activity ground to a halt some time in the 1730s, but was revived with renewed vigour in 1761. It was during this second period of activity that part of the Lodge of Antiquity, having quit the Grand Lodge of England in London, allied themselves with their Northern brethren and became, between 1779 and 1789, the Grand Lodge of All England South of the River Trent. Shortly after Antiquity's re-absorption into the London Grand Lodge she had founded, the Grand Lodge at York ceased to function again, this time for good. York LegendAccording to the Halliwell Manuscript, or Regius Poem, probably written in the second quarter of the fifteenth century, the birth of organised English masonry occurred when King Athelstan convened a grand council of the mason's trade. Later manuscripts added detail, and by the time of Queen Elizabeth I the assembly was acknowledged to have occurred in York in 926. It was convened by Athelstan's youngest son, Edwin, who appears in no other history of the period. This is usually referred to as the York Legend, or the Legend of the Guild. The masonic manuscripts known as the Old Charges all retell some version of this legend.[1] By the seventeenth century the Old Charges had assumed a standard form. After an introductory prayer or blessing the Seven Liberal Arts are described, and rooted in Geometry. There follows the story of the children of Lamech. His three sons invented masonry, metallurgy and music, and his daughter weaving. Being forewarned of the destruction of the world by fire or flood, they wrote their science on two great pillars, one which would not sink, and the other fireproof. The pillars were rediscovered after the flood, the knowledge passing from Hermes Trismegistus to Nimrod to Abraham, who carried it into Egypt where he taught it to Euclid. Euclid in turn, taught geometry/masonry to the children of the Lords of Egypt, whence it passed back to the children of Israel who in due course used it to build the Temple of Solomon. The diaspora of masons after the completion of the temple led to masonry arriving in the France of Charles Martel, whence it went to England under Saint Alban. The knowledge was lost in the wars after the death of Alban, but at Edwin's assembly at York he gave the masons their charges, and had them bring any writings they had inherited. Manuscripts in many languages were brought, and a book made showing how the craft was founded. The enduring myth of the "Grand Assembly" was continued in the first printed constitutions of the eighteenth century, making York the birthplace of English masonry, and allowing the old lodge at York to claim precedence over all the other English Lodges.[2] Early Freemasonry in YorkOriginsRecords of the operative lodge attached to York Minster are written on the Fabric rolls of York Minster (a record of the erection and maintenance of the fabric of the building), and extend from 1350 to 1639, when the lodge became irrelevant to the cathedral. Their rules appear under the heading Ordinacio Cementariorum in the roll from 1370. York Lodge has a manuscript constitution dated 1693, so presumably, the lodge is at least that old. The oldest, lost portion of the minutes of the speculative lodge commence on 7 March 1705–06. There may at one time have been minutes from 1704. The chief officer was styled President or Master until 1725, when Grand Master was adopted. Surviving minutes commence on 19 March 1712–13. Until 1725, there seems to have been only one lodge, its meetings termed Private and General lodges.[3] Familial relations have been traced between the members of the Ancient Society of Freemasons in the City of York, as recorded in 1705, and the operative lodge documented there in 1663. Some sort of organisational continuity is possible. It possessed its own collection of the Old Charges of the craft, and initiated masons to meet under its jurisdiction in at least two other towns. It assumed the geographical jurisdiction of the old operative Grand Lodge North of the River Trent. Its main meetings occurred twice a year on the feast days of John the Baptist and John the Evangelist.[4] From 1712–1716 there were one or two meetings a year, and from 1717–1721 there were no meetings at all.[5] Deputations were sent to other towns for the purpose of making masons, Scarborough in 1705, and Bradford in 1713, when eighteen gentlemen were admitted. Two important old constitutions, the Scarborough and the Hope manuscripts, are attributed to these meetings.[6] The end of the Scarborough MS states that it was certified at Scarborough on 10 July 1705 and is signed by the president and his officers. The end of the Hope MS is missing, thus the attribution is not so certain. The lodge would not again expand outside of York until the 1760s. In 1707, Robert Benson, the Lord Mayor of York, was president. Later, as Lord Bingham, he would become Chancellor of the Exchequer.[7] The Grand Lodge of All England On 27 December 1725, the feast of St. John the Evangelist, the York lodge claimed the status of a Grand Lodge. The burst of activity, which started earlier that year, may have been occasioned by the circulation of Anderson's constitutions, and the formation of a lodge at Durham under the jurisdiction of the London Grand Lodge. The minutes of 10 August 1725 describe William Scourfield as Worshipful Master. On 27 December, however, Brother Charles Bathurst was elected as Grand Master. His wardens (they were never referred to as Grand Wardens) were Brother Pawson and Francis Drake, the antiquarian, both of whom had only been initiated in September of that year. This occurred after a procession to Merchants Hall, and a banquet. They described themselves as a society and fraternity of free Masons. From 1722, visitors were admitted on examination. In 1725, Drake delivered a speech as Junior Warden, which went unrecorded. However, as the same persons were returned to office in 1726, his speech was written down. He characterised Freemasonry with the attributes of "Brotherly love, relief, and truth", and claimed superiority over the Southern Grand Lodge. They were, he said, content that the London lodge have the title Grand Master of England, but York claimed Totius Angliae (All England). The master of 1724, (now the treasurer) Scourfield, was expelled for making masons irregularly.[5] Drake's speech used the York Legend to claim precedence over all other English lodges, as the first lodge was established under Edwin of Northumbria around the year 600. Here, Edwin was not the brother or son of Athelstan, and the first lodge thereby became over three centuries older. Drake refers to three classes of Freemasons, working masons, other trades, and Gentlemen. Nineteen rules were enacted as Constitutions, and meetings moved from private houses to taverns.[3] After a space, the next minutes are from 21 June 1729. The minutes then become scarce and fall silent. In 1734 some masons travelled south to obtain authorisation for a lodge in York under the jurisdiction of the London Grand Lodge. 1761It was not until 1761 that the Grand Lodge was revived, under the Grand Mastership of Drake, for a period of renewed, and more successful activity. In 1767, they wrote to London informing them that their lodge No 259, in Stonegate, York, had ceased to meet, telling them, "This Lodge acknowledges no superiors and owes subjection to none; she exists in her own right, giving Constitutions and Certificate, in the same way as the Grand Lodge of England in London has asserted her claims there from time immemorial." On 31 July 1769, constitutions were granted to the Royal Oak lodge in Ripon, and on 30 October of the same year, Brothers Cateson, Revell, and Ketar were advanced to the degree of Master Mason, before being granted a constitution for the Crown in Boroughbridge. The Royal Arch Degree was introduced in 1768, and "Knights-Templars" by 1780. In 1777 London opened the Union lodge in York, but after negotiations during 1778, the rebel half of Antiquity were accepted in 1779 as the "only regular lodge in London". Antiquity, London's oldest and most prestigious lodge, had split following a dispute with their own Grand Lodge, who interpreted a walk from church to lodge in regalia by a few of their members as an unauthorised procession. At the centre of the controversy was William Preston, who mediated the move. These London Masons became, for ten years, The Grand Lodge of All England South of the River Trent.[5] The last minute is from 23 August 1792. Woodford believed that the lodge didn't cease to exist, it was simply absorbed by the larger Grand Lodge. Unlike other Grand Lodges, it enacted all the functions of a private lodge, as well as any regulatory duties that may have arisen.[3] RitualAfter 1761, there was worship at the church in Coney Street, followed by a procession to York's Guildhall for a banquet, attended by daughter lodges, ladies, and non-masons. The business of Grand Lodge, where ritual was used, followed the Banquet.[4] The operative masons having formed their own company in 1671, the Ancient Society used their copies of the Old Charges as warrants. Lodges which ceased to meet were expected to return their copy. Because the old operative lodge had admitted freemen who had passed their apprenticeship, the apprentice degree at York was largely symbolic, and until 1770 candidates were made Apprentice and Fellow on the same evening. The new degree of Master was administered separately. Candidates took an oath on a bible opened at the first chapter of St. John's Gospel. They were then invested with an apron, and seated at the lodge table, where they received their instruction. From 1760, the Royal Arch, and later the Knights Templar degrees were introduced. All the time, the lectures and catechisms attached to the degrees increased in complexity, a special award being presented to the past master who gave the best rendition.[4] Grand Lodge Minutes of 20 June 1780 show resolutions confirming the authority of the Grand Lodge over the Five degrees or Orders of Masonry. These were –

RegulationsThe regulations, or constitutions of the Grand Lodge, taken with Drake's speech in 1726, provide a window into sparsely documented world of the many independent lodges that refused to associate with the premier Grand Lodge in London.[4] These, together with the surviving regalia and minutes, are now the property of York Lodge No 236. "ARTICLES agreed to be kept and observed by the Ancient Society of Freemasons in the City of York, and to be subscribed by every Member thereof at their admittance into the said Society."

Subordinate Lodges

Under the Grand Lodge of All England South of the River Trent

Royal Arch Chapters

Knights Templar Encampments

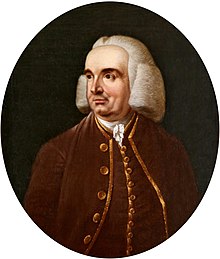

MastersNote – The stewardship of the presidents and masters at York dates from 27 December (the feast of St. John the Evangelist) in the year shown. For the most part of that year, the society will have been directed by their predecessor. Presidents 1704-Edward Thompson. Grand Masters 1726-Chas. Bathurst, Esq. The above from a letter of Jacob Bussey, Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of All England, addressed to Bro. B. Bradley, Junior Warden of the Lodge of Antiquity, London, and dated, York, 29 August 1778.[7] Last Period (Grand Secretaries in parentheses) 1761-2. Francis Drake, F.R.S. (John Tasker) References

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia