|

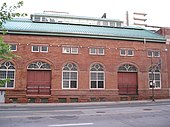

Fake buildingA fake building (also known as a fake house, false-front house, fake façade, or transformer house in specific situations) is a government building, structure, or public utility housing that uses urban and/or suburban camouflage, specifically with the intention to disguise equipment and city infrastructure facilities that some may consider aesthetically unpleasing in non-industrial neighborhoods.[1][2] HistoryPost-Industrial Revolution  After the Industrial Revolution, cities in industrialized countries were required to construct and maintain infrastructure facilities to support city growth. Originally, such infrastructure facilities weren't designed or intended to be concealed. For example, the pumping stations that housed large steam engines in the 19th and early 20th centuries were intentionally built to publicly communicate a message of safety and reliability in addition to expressing functionality. Additionally, building designs inherited from beam engine buildings required strong rigid walls and raised floors to support engines, large-arched and multi-story windows to allow natural light in, and roof ventilation via structures like decorative dormers. These functional features became known as "waterworks style." More elaborate designs were also used to communicate a sacred atmosphere and highlight the critical tasks performed at facilities like sewage pumping stations. An example of simple waterworks architectural style is the Springhead Pumping Station, while a baroque eclecticist example is the Abbey Mills Pumping Station.[3] Other types of infrastructure facilities—such as gas supply, electrical supply, and communications buildings—developed their own styles as well[4] Examples include the Radialsystem (sewage pumping station in Berlin), the Kempton Park Steam Engines house, the Chestnut Hill Waterworks (Massachusetts), the Spotswood Pumping Station (Melbourne), the Palacio de Aguas Corrientes (Buenos Aires), the Sewage Plant in Bubeneč (Prague), and the R. C. Harris Water Treatment Plant (Toronto). The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage considers the aforementioned buildings to be heritage sites of the global water industry.[5] Twentieth centuryUnurbanized substations An unconcealed electrical substation in Warren, Minnesota One of the earliest known examples of a fake building was 58 Joralemon Street in New York. The property was acquired by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company in 1907, after which it was internally transformed into infrastructure for ventilating underground transportation.[6] As a historic property, the local community wanted the façade to be historically appropriate and compatible with the neighborhood.[7] A few years later, in early 1911, substations were introduced to Toronto. Rather than being unenclosed, electronic converters were housed within fake buildings meant to imitate civic buildings such as museums and city halls.[8][9] After the end of World War II, suburban developments began to flourish all across the world.[10] As such, electric demand grew exponentially, leading architects to figure out where to place new substations. Harold Alphonso Bodwell, a utility employee appointed as a lead designer in Toronto, introduced the idea of disemboweling unused housing to set up substations within them.[11] Eventually, Toronto Hydro built house-shaped substations with six different base models ranging from ranch-style houses to Georgian mansions. Throughout the 20th century, the company went on to build hundreds of fake buildings in a litany of established styles.[9] In 1963, a property owner in Prairie Village, Kansas gave $300,000 to Johnson County Wastewater, a wastewater management authority, to build a fake building for a local sewage pumping station which would blend into the neighborhood. Very few in the neighborhood knew about it, as sewage smell was hardly reported in the area. Later, the same authority would go on to build another fake building for a pumping station.[12] Known locations Municipalities across the globe have used fake buildings for numerous purposes. Pump stations and subway ventilation shafts have often been subject to concealment by fake buildings.[14] Some also conceal the locations of secret facilities, such as chalets in Switzerland which hide military installations.[15] Such façades can be discovered in New York City,[16] Paris,[17] and London.[18] Specifically in Los Angeles, many fake buildings conceal oil rigs.[19][20] The following are further examples of fake buildings. For ventilation

For power conversion

For water and wastewater management

DesignDesign commonalities Printed images of windows rather than real glass panes, curtains or framing[23] Most fake buildings are intended to resemble the design of surrounding buildings, with some exceptions. Some may also fail to blend in due to design flaws caused by the contained equipment, such as blacked-out windows; [24][25][26] the lack of a roof,[27][25][28] doorway, window panes,[27] or some enclosed walls;[27] gated extrusions and/or heavy fencing; warning signs; industrial doors and windows; unusually pristine landscaping; security cameras; and/or some components printed on.[17][9] In municipalities that require public consultations for the construction of public facilities, the general public can command influence in the designs of fake buildings. When the City of Hoboken presented an initial design of a fake building to house a new flood pump station, some criticized it for looking more like a colonial townhouse and thus dishonoring the industrial heritage of the city. Ultimately, The final design was completely changed into a modern building with a similar design to a nearby transportation building.[29] Some fake buildings have designs that imitate other structures to match their surrounding areas. For example, an electrical substation in an urban neighborhood of Washington, D.C. was disguised as an old train station, while another substation in a mixed commercial and residential area of D.C. imitated an office building. In a more rural area of Gaithersburg, Maryland, a substation was designed to look like a large barn with a metal silo beside it.[30] References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Fake buildings. |

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia