Explosively pumped flux compression generator

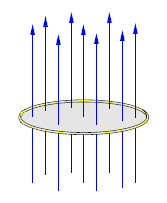

An explosively pumped flux compression generator (EPFCG) is a device used to generate a high-power electromagnetic pulse by compressing magnetic flux using high explosives. EPFCGs are physically destroyed during operation, making them single-use. They require a starting current pulse to operate, usually supplied by capacitors. Explosively pumped flux compression generators are used to create ultrahigh magnetic fields in physics and materials science research[1] and extremely intense pulses of electric current for pulsed power applications. They are being investigated as power sources for electronic warfare devices known as transient electromagnetic devices that generate an electromagnetic pulse without the costs, side effects, or enormous range of a nuclear electromagnetic pulse device. The first work on these generators was conducted by the VNIIEF center for nuclear research in Sarov in the Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1950s followed by Los Alamos National Laboratory in the United States. HistoryAt the start of the 1950s, the need for very short and powerful electrical pulses became evident to Soviet scientists conducting nuclear fusion research. The Marx generator, which stores energy in capacitors, was the only device capable at the time of producing such high power pulses. The prohibitive cost of the capacitors required to obtain the desired power motivated the search for a more economical device. The first magneto-explosive generators, which followed from the ideas of Andrei Sakharov, were designed to fill this role.[2][3] Mechanics Magneto-explosive generators use a technique called "magnetic flux compression", described in detail below. The technique is made possible when the time scales over which the device operates are sufficiently brief that resistive current loss is negligible, and the magnetic flux through any surface surrounded by a conductor (copper wire, for example) remains constant, even though the size and shape of the surface may change. This flux conservation can be demonstrated from Maxwell's equations. The most intuitive explanation of this conservation of enclosed flux follows from Lenz's law, which says that any change in the flux through an electric circuit will cause a current in the circuit which will oppose the change. For this reason, reducing the area of the surface enclosed by a closed loop conductor with a magnetic field passing through it, which would reduce the magnetic flux, results in the induction of current in the electrical conductor, which tends to keep the enclosed flux at its original value. In magneto-explosive generators, the reduction in area is accomplished by detonating explosives packed around a conductive tube or disk, so the resulting implosion compresses the tube or disk.[4] Since flux is equal to the magnitude of the magnetic field multiplied by the area of the surface, as the surface area shrinks the magnetic field strength inside the conductor increases. The compression process partially transforms the chemical energy of the explosives into the energy of an intense magnetic field surrounded by a correspondingly large electric current. The purpose of the flux generator can be either the generation of an extremely strong magnetic field pulse, or an extremely strong electric current pulse; in the latter case the closed conductor is attached to an external electric circuit. This technique has been used to create the most intense manmade magnetic fields on Earth; fields up to about 1000 teslas (about 1000 times the strength of a typical neodymium permanent magnet) can be created for a few microseconds. Elementary description of flux compression An external magnetic field (blue lines) threads a closed ring made of a perfect conductor (with zero resistance). The total magnetic flux through the ring is equal to the magnetic field multiplied by the area of the surface spanning the ring. The nine field lines represent the magnetic flux threading the ring.  Suppose the ring is deformed, reducing its cross-sectional area. The magnetic flux threading the ring, represented by five field lines, is reduced by the same ratio as the area of the ring. The variation of the magnetic flux induces a current (red arrows) in the ring by Faraday's law of induction, which in turn creates a new magnetic field circling the wire (green arrows) by Ampere's circuital law. The new magnetic field opposes the field outside the ring but adds to the field inside, so that the total flux in the interior of the ring is maintained: four green field lines added to the five blue lines give the original nine field lines.  By adding together the external magnetic field and the induced field, it can be shown that the net result is that the magnetic field lines originally threading the hole stay inside the hole, thus flux is conserved, and a current has been created in the conductive ring. The magnetic field lines are "pinched" closer together, so the (average) magnetic field intensity inside the ring increases by the ratio of the original area to the final area. The various types of generatorsThe simple basic principle of flux compression can be applied in a variety of different ways. Soviet scientists at the VNIIEF in Sarov, pioneers in this domain, conceived of three different types of generators:[5][3][6]

Such generators can, if necessary, be utilised independently, or even assembled in a chain of successive stages: the energy produced by each generator is transferred to the next, which amplifies the pulse, and so on. For example, it is foreseen that the DEMG generator will be supplied by a MK-2 type generator. Also, these can be either destructed just after an experiment, or used again and again while complying acceptable time to use.[7] Hollow tube generatorsIn the spring of 1952, R. Z. Lyudaev, E. A. Feoktistova, G. A. Tsyrkov, and A. A. Chvileva undertook the first experiment with this type of generator, with the goal of obtaining a very high magnetic field.  The MK-1 generator functions as follows:

The first experiments were able to attain magnetic fields of millions of gauss (hundreds of teslas), given an initial field of 30 kG (3 T) which is in the free space "air" the same as H = B/μ0 = (3 Vs/m2) / (4π × 10−7 Vs/Am) = 2.387×106 A/m (approximately 2.4 MA/m). Helical generatorsHelical generators were principally conceived to deliver an intense current to a load situated at a safe distance. They are frequently used as the first stage of a multi-stage generator, with the exit current used to generate a very intense magnetic field in a second generator.  The MK-2 generators function as follows:

The MK-2 generator is particularly interesting for the production of intense currents, up to 108 A (100 MA), as well as a very high energy magnetic field, as up to 20% of the explosive energy can be converted to magnetic energy, and the field strength can attain 2 × 106 gauss (200 T). The practical realization of high performance MK-2 systems required the pursuit of fundamental studies by a large team of researchers; this was effectively achieved by 1956, following the production of the first MK-2 generator in 1952, and the achievement of currents over 100 megaamperes from 1953. Disc generators A DEMG generator functions as follows:

Systems using up to 25 modules have been developed at VNIIEF. Output of 100 MJ at 256 MA have been produced by a generator a metre in diameter composed of three modules. See also

References

External links

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia