|

Emile Garcke Emile Oscar Garcke (1856 – 14 November 1930) was a naturalised British electrical engineer,[1] industrial, commercial and political entrepreneur[2] managing director of the British Electric Traction Company (BET),[3] and early author on accounting.[4] who is noted for writing the earliest standard text on cost accounting in 1887.[5] BiographyBorn in the Kingdom of Saxon in 1856, Garcke came to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland at an early age, becoming a naturalised British citizen in 1880.[6] In 1883 he became Secretary of the Anglo-American Brush Electric Light Corporation, was promoted to Manager in 1887 and became managing director of its successor company, Brush Electrical Engineering Company in 1891. In 1893 he was managing director of the Electric Construction Co and led its reorganisation.[6] He was a great believer in electric traction and set up the British Electric Traction Pioneer Co. in 1895. The following year he became managing director of the new company, now renamed British Electric Traction Co, which was involved in the electrification of tramways in Britain and abroad. The company became the largest private owner of tramways in the British Isles.[6] He was chairman of the council of the Industrial Co-partnership Association.[7] and helped to found the British Institute of Philosophical Studies. He wrote a number of articles about the use of electricity for the 1911 edition of Encyclopædia Britannica[8] for example the lemma on Electric lighting, and on the Telephone. He was also a keen publisher of electrical books, some of which were published as the “Manuals” series, such as Garcke's Manual of Electricity Supply, even after his death.[6] In London Garcke was the city's expert on electrical applications, and chaired the Electrical Committee of the London Chamber of Commerce.[9] Garcke was elected Fellow of Royal Statistical Society, and member of the Institute of Actuaries.[10] Garcke retired in 1929 and died in 1930. He had married Alice, the daughter of John Withers, and had a son Sidney.[6] WorkFactory accounts, their principles and practice, 1887 In 1887 Garcke and the accountant John Manger Fells (1858-1925) published their book Factory accounts, their principles and practice. In the preface of the second edition they presented their work as the "first attempt to place before English readers a systematised statement of the principles regulating Factory Accounts; and of the methods by which those principles can be put into practice and made to serve important purposes in the economy of manufacture."[11] While works on general accounting and new accounting methods had been written since the renaissance, Garcke and Fells specifically focussed on the cost accounting for manufacturing. The need for factory accountingIn the preface of the second edition of Factory Accounts (1889) Garcke and Fells further explained about the intention of this work.

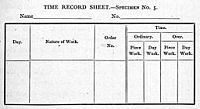

One of the special features of this work was the additional eight page long glossary of terms, while other authors in those days embedded the meaning of term within their text.[13] Forms for factory administrationA main part of Garcke and Fells' Factory Accounts (1889) relates to the administration of factory events, and specifically the administration of labour, shop orders, stores, and stock with special procedures and forms. The labour administration starts with the registration of labour time. This system is designed to secure, that "each person employed at a rate of pay on a time scale shall receive payment for the exact time employed."[14] It involved the cooperation of work people, the foreman, the time clerk and a timekeeper, and should exclude collusion and fraud. Forms for factory administration from Factory accounts, their principles and practice, 1889 The system includes multiple forms (see images):

Based on these information, wages can be paid at the end of each period. The flow diagram I (see below) shows the relation of these books and forms used in connection with wages. Late 19th and early 20th century these methods for timekeeping, payroll accounting, and piece-rate analysis would significantly improve in theory practice.[16] Garcke and Fells continued their work with methods for stock and stores accounting. Diemer (1904) considered this the most meritorious part of the work. He noted, that it shows "in complete detail a system of requisitions, purchase orders, and stores-accounting records, by means of which double-entry balances may be kept on stores. The principles of the system are sound. A competent storekeeper or purchasing agent should find no difficulty in adapting the ideas of the authors to the requirements of the particular business with which he is connected."[16] An overview of this system is pictured in the two flow diagrams (II en IV) below. System of factory accountingGarcke and Fells presented a system of factory accounting in which overall "prime costs were passed through a series of ledger accounts from raw materials to finished goods."[4] This concept initiated here, has hardly been improved ever since.[4] This system makes a division of two major types of costs, labour costs and material costs.

The system incorporated a work in process account. Hereto "materials and labor costs were transferred from stores and wages accounts to a summary manufacturing (work in process) account in the general ledger, which also received debits from the cashbook for expenditures directly applicable to the production process."[4] Periodically (diagram III) the "prime costs of goods completed were transferred from the manufacturing account to a stock (finished goods) account, leaving the work in process in manufacturing and accumulating cost of goods manufactured in stock."[4] The System of factory accounting was presented by a series of four diagrams, visualizing the foundations of factory accounting: Diagrams in Factory accounts, their principles and practice, 1889

Garcke and Fells (1889) commented, that they hoped that "the diagrams showing the relation between Factory and Commercial books will, with the numerous specimens the book contains, render the information we have to present of service to those who, while concerned in manufacture, and therefore interested in our subject, have not occasion to inquire closely into the practice of accounts."[11] The system of picturing manufacturing accounts has been further developed by J. Slater Lewis and others (see here), including James Alexander Lyons, who pictured various patterns of closing Loss & Gain accounts (see here). Allocation of indirect costs and depreciationAn important element in Garcke and Fells' method of cost accounting was the allocation of indirect costs. They "suggested allocating the 'indirect costs' of producing a good proportionally to the amount of labour and materials costs used to make the item."[17] As they (1887) explained:

According to Diewert (2001), the method proposed here was "rather crude" in compare to the "masterful analysis," that Alexander Hamilton Church would give in his 1908 "The Proper Distribution of Expense Burden."[17] Another innovation by Garcke and Fells was the "idea that deprecation was an admissible item of cost that should be allocated in proportion to the prime cost (i.e., labour and materials cost) of manufacturing an article but they explicitly ruled out interest as a cost."[17] They explained:

Diewert (2001) noticed that "the aversion of accountants to include interest as a cost can be traced back to this quotation."[17] ReceptionEarly 20th centuryLate 19th century and early 20th century Factory accounts, their principles and practice by Garcke and Fells turned out to be a popular and influential work on cost accounting. It was republished until the last 7th edition in 1922.[20] In 1910 J.M. Fells himself in The Accountancy, looked back and made the following remarks:

Fells is referring here to the words of an accountant, which was already mentioned the preface of the 2nd edition of their work (1889, p. 4). Now in 1910 Fells continued:

In his Bibliography of Works Management Hugo Diemer (1904) listed Garcke and Fells' work among the foremost works on work management. Diemer summarized, that "In a preface the authors state that their aim has been to show that as great a degree of accuracy can be attained in factory bookkeeping as in commercial accounts." And furthermore:

Diemer (1904) already stipulated, what Diewert (2001), Boyns (2006) and Parker (2013) confirms, that the matter of the distribution of indirect costs was not worked out that well. Diemer described "the matter of labor costs and distribution of indirect expenses has not been worked out as fully as the stores problem. The double-entry balance principle is carried still further into a method of balancing the manufactured stock ledger accounts with the commercial ledger. Charts built up of circles and arrows, and tracing the relationships of forms and accounts, serve to simplify the schemes proposed, and to make clear the underlying principles."[16] 21st centuryTrevor Boyns & John Richard Edwards (2006) acknowledged the Factory accounts, their principles and practice as the "earliest standard text on cost accounting,"[5] It marked the beginning of modern cost accounting; the process of collecting, analyzing, summarizing and evaluating various alternative courses of action. It was however so that this work primary focussed on the identification and classification of costs. The scope of the field of cost accounting has further developed in the use of accounting methods as aid to management.[5] Parker (2013) concluded that Garcke and Fells had written a leading book on cost accounting, but that their impact on accounting for decision making and control was limited. A restriction in their work was their argument that "all manufacturing costs fluctuated with the cost of labour and the price of material, and should therefore be allocated to products."[23] On the other hand, they assumed that "the 'establishment expenses' (by which they meant administrative and selling costs) were, in the aggregate, more or less constant and should not be so allocated, because that would 'have the effect of disproportionately reducing the cost of each, with every increase, and the reverse with every diminution of business'."[23] In comparison with the contemporary understanding of fixed costs and variable cost, the distinction made here is still limited.[23] Selected publicationsBooks:

Annual review:

Articles, a selection:

References

External linksWikisource has original text related to this article:

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Emile Garcke.

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia