|

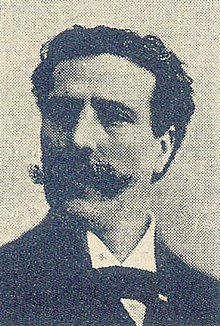

Eduardo Acevedo Díaz

Eduardo Acevedo Díaz (20 April 1851 – 18 June 1921[citation needed]a), was an Uruguayan writer,[1] politician and journalist. Early lifeHe was born in Villa de la Unión, Montevideo, the son of Fátima Díaz and Norberto Acevedo (brother of Eduardo Acevedo Maturana, whom Acevedo Díaz named "uncle Eduardo"). His maternal grandfather was General Antonio Díaz, who was a minister of the tenure of Manuel Oribe in the Gobierno del Cerrito. Between 1866 and 1868, he earned his baccalaureate degree and in the process became friendly with Pablo de Maria and Justino Jiménez de Aréchaga in the Greater University of the Republic.[citation needed] In 1868, he was associated the University Club. He entered the Faculty of Law in 1869. On 18 September 1869, he published, in the Century, his first article, a tribute to his maternal grandfather who had died six days before. In April 1870, he left University to join the revolutionary movement of Timoteo Aparicio against the Colorado government of Lorenzo Batlle.[citation needed] PoliticsHe wrote of the aim of the Revolution of Lanzas, in an article entitled "a tomb in the forest" published in the newspaper the Republic in 1872. He signed the manifesto "Profession of a Rationalist Faith" in 1872, which asserted the immortality of the soul and the existence of the Supreme God in opposition to the Pope.[citation needed] The three-month Revolutionary War was concluded in July 1872, and in Montevideo, Diaz began the militarization of the National Party. He wrote for Democracy in 1873, and started the Uruguayan Magazine in 1875.[citation needed] From these organs of press, Varela attacked the Pedro government, and he was sent into exile. After the failure of the Tricolor revolution against the government, he settled in Argentina, where he continued his journalistic activities living in Plata and Dolores. He returned to Uruguay, but his critics (Lorenzo Latorre) from the Democracy forced him to flee to Buenos Aires. On his return to Montevideo, he founded the National (important in the history of the Uruguayan media).[citation needed] He was made a senator by the National Party and took part in the second insurrection led by the nationalist Caudillo Aparicio Saravia, in 1897. He was a member of the Council of State in 1898, but moved away politically from Saravia in later years, deciding to support José Batlle y Ordñez. This distanced him from the National Party, which he explained in a Political Letter published in the National. Batlle sent him on diplomatic missions to various countries in Europe and to America, from 1904 to 1914. Death and remembranceHe did not return to Uruguay but died in Buenos Aires, Argentina,[2] on 18 June 1921, requesting that his remains not be repatriated to his homeland.[citation needed] One of the chairs of the National Academy of Letters of Uruguay was named in his honor, in recognition of his work.[citation needed] Works

Stories

Plays

See also

NotesCitations

References

External links

|

||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia