|

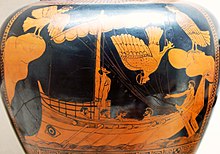

Commitment device A commitment device is, according to journalist Stephen J. Dubner and economist Steven Levitt, a way to lock oneself into following a plan of action that one might not want to do, but which one knows is good for oneself.[1] In other words, a commitment device is a way to give oneself a reward or punishment to make what might otherwise become an empty promise stronger and believable.[2] A commitment device is a technique where someone makes it easier for themselves to avoid akrasia (acting against one's better judgment), particularly procrastination. Commitment devices have two major features. They are voluntarily adopted for use and they tie consequences to follow-through failures.[3] Consequences can be immutable (irreversible, such as a monetary consequence) or mutable (allows for the possibility of future reversal of the consequence).[3] Overview The term "commitment device" is used in both economics and game theory. In particular, the concept is relevant to the fields of economics and especially the study of decision making.[4] A common example comes from mythology: Odysseus' plan to survive hearing the sirens' song without jumping overboard. Economist Jodi Beggs writes "Commitment devices are a way to overcome the discrepancy between an individual's short-term and long-term preferences; in other words, they are a way for self-aware people to modify their incentives or set of possible choices in order to overcome impatience or other irrational behavior. You know the story of Ulysses tying himself to the mast so that he couldn't be lured in by the song of the Sirens? You can think of that as the quintessential commitment device".[5] Behavioral economist Daniel Goldstein describes how commitment devices established in "cold states" help and protect themselves against impulsive decisions in later, emotional, stimulated, "hot states". Goldstein says that, despite their usefulness, commitment devices nevertheless have drawbacks. Namely, they still rely on some self-control.[6] Goldstein says that, for one, a commitment device can promote learned helplessness in the agent. If the agent enters a situation where the device does not incentivize commitment, the agent may not have enough will power or ability to control themselves. (Goldstein uses the example of a cake falling into the grey area of a diet, so it is eaten excessively.) Second, commitment devices can usually be reversed. (An unplugged distracting electronic can be plugged back in.) [6] Goldstein says "In effect you are like Odysseus and the first mate in one person. You're binding yourself, and then you're weaseling your way out of it, and then you're beating yourself up for it afterwards."[6] Methods

ChallengesIt can be challenging to promote uptake of commitment devices. In the field of health, for example, commitment devices have the potential to increase patient adherence to their health goals, but utilization of these techniques is low.[7][3] Health professionals can potentially increase patient uptake of commitment devices by increasing their accessibility, making policies opt-out, and leveraging patients’ social networks.[3] Other examples Examples of commitment devices abound. Dubner and Levitt give the example of Han Xin, a general in Ancient China, who positioned his soldiers with their backs to a river, making it impossible for them to flee, thereby leaving them no choice but to attack the enemy head-on. They also present various commitment devices related to weight loss.[8] In addition, some game theorists have argued that human emotions and sense of honor are forms of commitment device.[9] Other examples include announcing commitments publicly and mutually assured destruction,[10] as well as software programs that block internet access for a predetermined period of time. Filmmaker Alice Wu successfully employed a commitment device to complete the screenplay for The Half of It. Wu wrote a $1000 check to the National Rifle Association of America (an organization she doesn't support) and asked a friend to mail it in if Wu didn't complete the screenplay in five weeks.[11] See also

References

Further reading

External links

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia