|

Chiapas

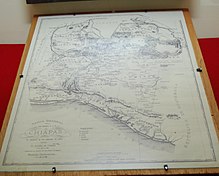

Chiapas,[b] officially the Free and Sovereign State of Chiapas,[c] is one of the states that make up the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It comprises 124 municipalities as of September 2017[update][8][9] and its capital and largest city is Tuxtla Gutiérrez. Other important population centers in Chiapas include Ocosingo, Tapachula, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Comitán, and Arriaga. Chiapas is the southernmost state in Mexico, and it borders the states of Oaxaca to the west, Veracruz to the northwest, and Tabasco to the north,[10] and the Petén, Quiché, Huehuetenango, and San Marcos departments of Guatemala to the east and southeast. Chiapas has a significant coastline on the Pacific Ocean to the southwest. In general, Chiapas has a humid, tropical climate. In the northern area bordering Tabasco, near Teapa, rainfall can average more than 3,000 mm (120 in) per year. In the past, natural vegetation in this region was lowland, tall perennial rainforest, but this vegetation has been almost completely cleared to allow agriculture and ranching. Rainfall decreases moving towards the Pacific Ocean, but it is still abundant enough to allow the farming of bananas and many other tropical crops near Tapachula. On the several parallel sierras or mountain ranges running along the center of Chiapas, the climate can be quite moderate and foggy, allowing the development of cloud forests like those of Reserva de la Biosfera El Triunfo, home to a handful of horned guans, resplendent quetzals, and azure-rumped tanagers. Chiapas is home to the ancient Mayan ruins of Palenque, Yaxchilán, Bonampak, Lacanha, Chinkultic, El Lagartero and Toniná. It is also home to one of the largest indigenous populations in the country, with twelve federally recognized ethnicities.[11] HistoryThe official name of the state is Chiapas, which is believed to have come from the ancient city of Chiapan, which in Náhuatl means "the place where the chia sage grows."[12] After the Spanish arrived (1522), they established two cities called Chiapas de los Indios and Chiapas de los Españoles (1528), with the name of Provincia de Chiapas for the area around the cities. The first coat of arms of the region dates from 1535 as that of the Ciudad Real (San Cristóbal de las Casas). Chiapas painter Javier Vargas Ballinas designed the modern coat of arms.[13][need quotation to verify] Pre-Columbian EraHunter gatherers began to occupy the central valley of the state around 7000 BCE, but little is known about them. The oldest archaeological remains in the seat are located at the Santa Elena Ranch in Ocozocoautla whose finds include tools and weapons made of stone and bone. It also includes burials.[14] In the pre Classic period from 1800 BCE to 300 CE, agricultural villages appeared all over the state although hunter gather groups would persist for long after the era.[15] Recent excavations in the Soconusco region of the state indicate that the oldest civilization to appear in what is now modern Chiapas is that of the Mokaya, which were cultivating corn and living in houses as early as 1500 BCE, making them one of the oldest in Mesoamerica.[15][16] There is speculation that these were the forefathers of the Olmec, migrating across the Grijalva Valley and onto the coastal plain of the Gulf of Mexico to the north, which was Olmec territory. One of these people's ancient cities is now the archeological site of Chiapa de Corzo, in which was found the oldest calendar known on a piece of ceramic with a date of 36 BCE. This is three hundred years before the Mayans developed their calendar. The descendants of Mokaya are the Mixe-Zoque.[15]  During the pre Classic era, it is known that most of Chiapas was not Olmec, but had close relations with them, especially the Olmecs of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Olmec-influenced sculpture can be found in Chiapas and products from the state including amber, magnetite, and ilmenite were exported to Olmec lands. The Olmecs came to what is now the northwest of the state looking for amber with one of the main pieces of evidence for this called the Simojovel Ax.[17]  Mayan civilization began in the pre-Classic period as well, but did not come into prominence until the Classic period (300–900 CE). Development of this culture was agricultural villages during the pre-Classic period with city building during the Classic as social stratification became more complex. The Mayans built cities on the Yucatán Peninsula and west into Guatemala. In Chiapas, Mayan sites are mostly concentrated along the state's borders with Tabasco and Guatemala, near Mayan sites in those entities. Most of this area belongs to the Lacandon Jungle.[18]  Mayan civilization in the Lacandon area is marked by rising exploitation of rain forest resources, rigid social stratification, fervent local identity, waging war against neighboring peoples.[15] At its height, it had large cities, a writing system, and development of scientific knowledge, such as mathematics and astronomy. Cities were centered on large political and ceremonial structures elaborately decorated with murals and inscriptions. Among these cities are Palenque, Xupa, Bonampak, Lacanha, Yaxchilan, Chinkultic, Toniná, Chinikiha, El Cayo, La Mar, El Palma, Oxlahuntun and Sak Tz'i. The Mayan civilization had extensive trade networks and large markets trading in goods such as animal skins, indigo, amber, vanilla and quetzal feathers.[18] It is not known what ended the civilization but theories range from over population size, natural disasters, disease, and loss of natural resources through over exploitation or climate change. Nearly all Mayan cities collapsed around the same time, 900 CE. From then until 1500 CE, social organization of the region fragmented into much smaller units and social structure became much less complex. There was some influence from the rising powers of central Mexico but two main indigenous groups emerged during this time, the Zoques and the various Mayan descendants. The Chiapans, for whom the state is named, migrated into the center of the state during this time and settled around Chiapa de Corzo, the old Mixe–Zoque stronghold.[15] There is evidence that the Aztecs appeared in the center of the state around Chiapa de Corza in the 15th century, but were unable to displace the native Chiapa tribe. However, they had enough influence so that the name of this area and of the state would come from Nahuatl.[19] Colonial period When the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, they found the indigenous peoples divided into Mayan and non-Mayan, with the latter dominated by the Zoques and Chiapanecas.[15] The first contact between Spaniards and the people of Chiapas came in 1522, when Hernán Cortés sent tax collectors to the area after Aztec Empire was subdued. The first military incursion was headed by Luis Marín, who arrived in 1523. After three years, Marín was able to subjugate a number of the local peoples, but met with fierce resistance from the Tzotzils in the highlands. The Spanish colonial government then sent a new expedition under Diego de Mazariegos. Mazariegos had more success than his predecessor, but many natives preferred to commit suicide rather than submit to the Spanish. One famous example of this is the Battle of Tepetchia, where many jumped to their deaths in the Sumidero Canyon.[20][21] Indigenous resistance was weakened by continual warfare with the Spaniards and disease. By 1530 almost all of the indigenous peoples of the area had been subdued with the exception of the Lacandons in the deep jungles who actively resisted until 1695.[15][19][20] However, the main two groups, the Tzotzils and Tzeltals of the central highlands were subdued enough to establish the first Spanish city, today called San Cristóbal de las Casas, in 1528. It was one of two settlements initially called Villa Real de Chiapa de los Españoles and the other called Chiapa de los Indios.[20][21]  Soon after, the encomienda system was introduced, which reduced most of the indigenous population to serfdom and many even as slaves as a form of tribute and way of locking in a labor supply for tax payments. The conquistadors brought previously unknown diseases. This, as well as overwork on plantations, dramatically decreased the indigenous population.[15] The Spanish also established missions, mostly under the Dominicans, with the Diocese of Chiapas established in 1538 by Pope Paul III.[21] The Dominican evangelizers became early advocates of the indigenous' people's plight, with Bartolomé de las Casas winning a battle with the passing of a law in 1542 for their protection. This order also worked to make sure that communities would keep their indigenous name with a saint's prefix leading to names such as San Juan Chamula and San Lorenzo Zinacantán. He also advocated adapting the teaching of Christianity to indigenous language and culture. The encomienda system that had perpetrated much of the abuse of the indigenous peoples declined by the end of the 16th century, and was replaced by haciendas. However, the use and misuse of Indian labor remained a large part of Chiapas politics into modern times.[15][20][21] Maltreatment and tribute payments created an undercurrent of resentment in the indigenous population that passed on from generation to generation. One uprising against high tribute payments occurred in the Tzeltal communities in the Los Alto region in 1712. Soon, the Tzoltzils and Ch'ols joined the Tzeltales in rebellion, but within a year the government was able to extinguish the rebellion.[20] As of 1778, Thomas Kitchin described Chiapas as "the metropolis of the original Mexicans," with a population of approximately 20,000, and consisting mainly of indigenous peoples.[22] The Spanish introduced new crops such as sugar cane, wheat, barley and indigo as main economic staples along native ones such as corn, cotton, cacao and beans. Livestock such as cattle, horses and sheep were introduced as well. Regions would specialize in certain crops and animals depending on local conditions and for many of these regions, communication and travel were difficult.[15] Most Europeans and their descendants tended to concentrate in cities such as Ciudad Real, Comitán, Chiapa and Tuxtla. Intermixing of the races was prohibited by colonial law but by the end of the 17th century there was a significant mestizo population. Added to this was a population of African slaves brought in by the Spanish in the middle of the 16th century due to the loss of native workforce.[15][23] Initially, "Chiapas" referred to the first two cities established by the Spanish in what is now the center of the state and the area surrounding them. Two other regions were also established, the Soconusco and Tuxtla, all under the regional colonial government of Guatemala. Chiapas, Soconusco and Tuxla regions were united to the first time as an intendencia during the Bourbon Reforms in 1790 as an administrative region under the name of Chiapas. However, within this intendencia, the division between Chiapas and Soconusco regions would remain strong and have consequences at the end of the colonial period.[15][16] Era of IndependenceFrom the colonial period Chiapas was relatively isolated from the colonial authorities in Mexico City and regional authorities in Guatemala. One reason for this was the rugged terrain. Another was that much of Chiapas was not attractive to the Spanish. It lacked mineral wealth, large areas of arable land, and easy access to markets.[15] This isolation spared it from battles related to Independence. José María Morelos y Pavón did enter the city of Tonalá but incurred no resistance. The only other insurgent activity was the publication of a newspaper called El Pararrayos by Matías de Córdova in San Cristóbal de las Casas.[24]    Following the end of Spanish rule in New Spain, it was unclear what new political arrangements would emerge. The isolation of Chiapas from centers of power, along with the strong internal divisions in the intendencia caused a political crisis after the royal government collapsed in Mexico City in 1821, ending the Mexican War of Independence.[15] During this war, a group of influential Chiapas merchants and ranchers sought the establishment of the Free State of Chiapas. This group became known as the La Familia Chiapaneca. However, this alliance did not last with the lowlands preferring inclusion among the new republics of Central America and the highlands annexation to Mexico.[25] In 1821, a number of cities in Chiapas, starting in Comitán, declared the state's separation from the Spanish empire. In 1823, Guatemala became part of the United Provinces of Central America, which united to form a federal republic that would last from 1823 to 1839. With the exception of the pro-Mexican Ciudad Real (San Cristóbal) and some others, many Chiapanecan towns and villages favored a Chiapas independent of Mexico and some favored unification with Guatemala. Elites in highland cities pushed for incorporation into Mexico.[15][20] In 1822, then-Emperor Agustín de Iturbide decreed that Chiapas was part of Mexico. In 1823, the Junta General de Gobierno was held and Chiapas declared independence again.[15] In July 1824, the Soconusco District of southwestern Chiapas split off from Chiapas, announcing that it would join the Central American Federation.[20] In September of the same year, a referendum was held on whether the intendencia would join Central America or Mexico, with many of the elite endorsing union with Mexico. This referendum ended in favor of incorporation with Mexico (allegedly through manipulation of the elite in the highlands), but the Soconusco region maintained a neutral status until 1842, when Oaxacans under General Antonio López de Santa Anna occupied the area, and declared it reincorporated into Mexico. Elites of the area would not accept this until 1844.[15][25][26] Guatemala would not recognize Mexico's annexation of the Soconusco region until 1895, even though the border between Chiapas and Guatemala had been agreed upon in 1882.[20][26] The State of Chiapas was officially declared in 1824, with its first constitution in 1826. Ciudad Real was renamed San Cristóbal de las Casas in 1828.[16] In the decades after the official end of the war, the provinces of Chiapas and Soconusco unified, with power concentrated in San Cristóbal de las Casas. The state's society evolved into three distinct spheres: indigenous peoples, mestizos from the farms and haciendas and the Spanish colonial cities. Most of the political struggles were between the last two groups especially over who would control the indigenous labor force. Economically, the state lost one of its main crops, indigo, to synthetic dyes. There was a small experiment with democracy in the form of "open city councils" but it was short-lived because voting was heavily rigged.[15] The Universidad Pontificia y Literaria de Chiapas was founded in 1826, with Mexico's second teacher's college founded in the state in 1828.[15] Era of the Liberal ReformWith the ouster of conservative Antonio López de Santa Anna, Mexican liberals came to power. The Reform War (1858–1861) fought between Liberals, who favored federalism and sought economic development, decreased power of the Roman Catholic Church, and Mexican army, and Conservatives, who favored centralized autocratic government, retention of elite privileges, did not lead to any military battles in the state. Despite that it strongly affected Chiapas politics.[15] In Chiapas, the Liberal-Conservative division had its own twist. Much of the division between the highland and lowland ruling families was for whom the Indians should work for and for how long as the main shortage was of labor.[27] These families split into Liberals in the lowlands, who wanted further reform and Conservatives in the highlands who still wanted to keep some of the traditional colonial and church privileges.[28] For most of the early and mid 19th century, Conservatives held most of the power and were concentrated in the larger cities of San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapa (de Corzo), Tuxtla and Comitán. As Liberals gained the upper hand nationally in the mid-19th century, one Liberal politician Ángel Albino Corzo gained control of the state. Corzo became the primary exponent of Liberal ideas in the southeast of Mexico and defended the Palenque and Pichucalco areas from annexation by Tabasco. However, Corzo's rule would end in 1875, when he opposed the regime of Porfirio Díaz.[15] Liberal land reforms would have negative effects on the state's indigenous population unlike in other areas of the country. Liberal governments expropriated lands that were previously held by the Spanish Crown and Catholic Church in order to sell them into private hands. This was not only motivated by ideology, but also due to the need to raise money. However, many of these lands had been in a kind of "trust" with the local indigenous populations, who worked them. Liberal reforms took away this arrangement and many of these lands fell into the hands of large landholders who when made the local Indian population work for three to five days a week just for the right to continue to cultivate the lands. This requirement caused many to leave and look for employment elsewhere. Most became "free" workers on other farms, but they were often paid only with food and basic necessities from the farm shop. If this was not enough, these workers became indebted to these same shops and then unable to leave.[29] The opening up of these lands also allowed many whites and mestizos (often called Ladinos in Chiapas) to encroach on what had been exclusively indigenous communities in the state. These communities had had almost no contact with the Ladino world, except for a priest. The new Ladino landowners occupied their acquired lands as well as others, such as shopkeepers, opened up businesses in the center of Indian communities. In 1848, a group of Tzeltals plotted to kill the new mestizos in their midst, but this plan was discovered, and was punished by the removal of large number of the community's male members. The changing social order had severe negative effects on the indigenous population with alcoholism spreading, leading to more debts as it was expensive.[27] The struggles between Conservatives and Liberals nationally disrupted commerce and confused power relations between Indian communities and Ladino authorities. It also resulted in some brief respites for Indians during times when the instability led to uncollected taxes.[30] One other effect that Liberal land reforms had was the start of coffee plantations, especially in the Soconusco region. One reason for this push in this area was that Mexico was still working to strengthen its claim on the area against Guatemala's claims on the region. The land reforms brought colonists from other areas of the country as well as foreigners from England, the United States and France. These foreign immigrants would introduce coffee production to the areas, as well as modern machinery and professional administration of coffee plantations. Eventually, this production of coffee would become the state's most important crop.[31] Although the Liberals had mostly triumphed in the state and the rest of the country by the 1860s, Conservatives still held considerable power in Chiapas. Liberal politicians sought to solidify their power among the indigenous groups by weakening the Roman Catholic Church. The more radical of these even allowed indigenous groups the religious freedoms to return to a number of native rituals and beliefs such as pilgrimages to natural shrines such as mountains and waterfalls.[32] This culminated in the Chiapas "caste war", which was an uprising of Tzotzils beginning in 1868.[20][33] The basis of the uprising was the establishment of the "three stones cult" in Tzajahemal.[33] Agustina Gómez Checheb was a girl tending her father's sheep when three stones fell from the sky. Collecting them, she put them on her father's altar and soon claimed that the stone communicated with her. Word of this soon spread and the "talking stones" of Tzajahemel soon became a local indigenous pilgrimage site. The cult was taken over by one pilgrim, Pedro Díaz Cuzcat, who also claimed to be able to communicate with the stones, and had knowledge of Catholic ritual, becoming a kind of priest. However, this challenged the traditional Catholic faith and non Indians began to denounce the cult.[34] Stories about the cult include embellishments such as the crucifixion of a young Indian boy.[25] This led to the arrest of Checheb and Cuzcat in December 1868. This caused resentment among the Tzotzils. Although the Liberals had earlier supported the cult, Liberal landowners had also lost control of much of their Indian labor and Liberal politicians were having a harder time collecting taxes from indigenous communities.[35] An Indian army gathered at Zontehuitz then attacked various villages and haciendas.[26] By the following June the city of San Cristóbal was surrounded by several thousand Indians, who offered the exchanged of several Ladino captives for their religious leaders and stones.[36] Chiapas governor Dominguéz came to San Cristóbal with about three hundred heavily armed men, who then attacked the Indian force armed only with sticks and machetes.[37] The indigenous force was quickly dispersed and routed with government troops pursuing pockets of guerrilla resistance in the mountains until 1870. The event effectively returned control of the indigenous workforce back to the highland elite.[26][38] Porfiriato, 1876–1911The Porfirio Díaz era at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th was initially thwarted by regional bosses called caciques, bolstered by a wave of Spanish and mestizo farmers who migrated to the state and added to the elite group of wealthy landowning families.[15][20] There was some technological progress such as a highway from San Cristóbal to the Oaxaca border and the first telephone line in the 1880s, but Porfirian era economic reforms would not begin until 1891 with Governor Emilio Rabasa.[15][26] This governor took on the local and regional caciques and centralized power into the state capital, which he moved from San Cristóbal de las Casas to Tuxtla in 1892.[26][39] He modernized public administration, transportation and promoted education.[15] Rabasa also introduced the telegraph, limited public schooling, sanitation and road construction, including a route from San Cristóbal to Tuxtla then Oaxaca, which signaled the beginning of favoritism of development in the central valley over the highlands.[40] He also changed state policies to favor foreign investment, favored large land mass consolidation for the production of cash crops such as henequen, rubber, guayule, cochineal and coffee.[15][41] Agricultural production boomed, especially coffee, which induced the construction of port facilities in Tonalá. The economic expansion and investment in roads also increased access to tropical commodities such as hardwoods, rubber and chicle.[40] These still required cheap and steady labor to be provided by the indigenous population.[40] By the end of the 19th century, the four main indigenous groups, Tzeltals, Tzotzils, Tojolabals and Ch’ols were living in "reducciones" or reservations, isolated from one another.[42] Conditions on the farms of the Porfirian era was serfdom, as bad if not worse than for other indigenous and mestizo populations leading to the Mexican Revolution. While this coming event would affect the state, Chiapas did not follow the uprisings in other areas that would end the Porfirian era.[43] Japanese immigration to Mexico began in 1897 when the first thirty five migrants arrived in Chiapas to work on coffee farms, so that Mexico was the first Latin American country to receive organized Japanese immigration.[44] Although this colony ultimately failed, there remains a small Japanese community in Acacoyagua, Chiapas. Early 20th century to 1960   In the early 20th century and into the Mexican Revolution, the production of coffee was particularly important but labor-intensive. This would lead to a practice called enganche (hook), where recruiters would lure workers with advanced pay and other incentives such as alcohol and then trap them with debts for travel and other items to be worked off. This practice would lead to a kind of indentured servitude and uprisings in areas of the state, although they never led to large rebel armies as in other parts of Mexico.[31] A small war broke out between Tuxtla Gutiérrez and San Cristobal in 1911. San Cristóbal, allied with San Juan Chamula, tried to regain the state's capital but the effort failed. San Cristóbal de las Casas, which had a very limited budget, to the extent that it had to ally with San Juan Chamula challenged Tuxtla Gutierrez which, with only a small ragtag army overwhelmingly defeated the army helped by chamulas from San Cristóbal. There were three years of peace after that until troops allied with the "First Chief" of the revolutionary Constitutionalist forces, Venustiano Carranza, entered in 1914 taking over the government, with the aim of imposing the Ley de Obreros (Workers' Law) to address injustices against the state's mostly indigenous workers. Conservatives responded violently months later when they were certain the Carranza forces would take their lands. This was mostly by way of guerrilla actions headed by farm owners who called themselves the Mapaches. This action continued for six years, until President Carranza was assassinated in 1920 and revolutionary general Álvaro Obregón became president of Mexico. This allowed the Mapaches to gain political power in the state and effectively stop many of the social reforms occurring in other parts of Mexico. The Mapaches continued to fight against socialists and communists in Mexico from 1920 to 1936, to maintain their control over the state.[16] In general, elite landowners also allied with the nationally dominant party founded by Plutarco Elías Calles following the assassination of president-elect Obregón in 1928; that party was renamed the Institutional Revolutionary Party in 1946. Through that alliance, they could block land reform in this way as well.[19] The Mapaches were first defeated in 1925 when an alliance of socialists and former Carranza loyalists had Carlos A. Vidal selected as governor, although he was assassinated two years later. The last of the Mapache resistance was overcome in the early 1930s by Governor Victorico Grajales, who pursued President Lázaro Cárdenas' social and economic policies including persecution of the Catholic Church. These policies would have some success in redistributing lands and organizing indigenous workers but the state would remain relatively isolated for the rest of the 20th century.[15][16] The territory was reorganized into municipalities in 1916. The current state constitution was written in 1921.[15] There was political stability from the 1940s to the early 1970s; however, regionalism regained with people thinking of themselves as from their local city or municipality over the state. This regionalism impeded the economy as local authorities restrained outside goods. For this reason, construction of highways and communications were pushed to help with economic development. Most of the work was done around Tuxtla Gutiérrez and Tapachula. This included the Sureste railroad connecting northern municipalities such as Pichucalco, Salto de Agua, Palenque, Catazajá and La Libertad. The Cristobal Colon highway linked Tuxtla to the Guatemalan border. Other highways included El Escopetazo to Pichucalco, a highway between San Cristóbal and Palenque with branches to Cuxtepeques and La Frailesca. This helped to integrate the state's economy, but it also permitted the political rise of communal land owners called ejidatarios.[15]  Mid-20th century to 1990In the mid-20th century, the state experienced a significant rise in population, which outstripped local resources, especially land in the highland areas.[45] Since the 1930s, many indigenous and mestizos have migrated from the highland areas into the Lacandon Jungle with the populations of Altamirano, Las Margaritas, Ocosingo and Palenque rising from less than 11,000 in 1920 to over 376,000 in 2000. These migrants came to the jungle area to clear forest and grow crops and raise livestock, especially cattle.[15][46] Economic development in general raised the output of the state, especially in agriculture, but it had the effect of deforesting many areas, especially the Lacandon. Added to this was there were still serf like conditions for many workers and insufficient educational infrastructure. Population continued to increase faster than the economy could absorb.[15] There were some attempts to resettle peasant farmers onto non cultivated lands, but they were met with resistance. President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz awarded a land grant to the town of Venustiano Carranza in 1967, but that land was already being used by cattle-ranchers who refused to leave. The peasants tried to take over the land anyway, but when violence broke out, they were forcibly removed.[47] In Chiapas poor farmland and severe poverty afflict the Mayan Indians which led to unsuccessful non violent protests and eventually armed struggle started by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in January 1994.[48] These events began to lead to political crises in the 1970s, with more frequent land invasions and takeovers of municipal halls.[15][47] This was the beginning of a process that would lead to the emergence of the Zapatista movement in the 1990s. Another important factor to this movement would be the role of the Catholic Church from the 1960s to the 1980s. In 1960, Samuel Ruiz became the bishop of the Diocese of Chiapas, centered in San Cristóbal. He supported and worked with Marist priests and nuns following an ideology called liberation theology. In 1974, he organized a statewide "Indian Congress" with representatives from the Tzeltal, Tzotzil, Tojolabal and Ch'ol peoples from 327 communities as well as Marists and the Maoist People's Union. This congress was the first of its kind with the goal of uniting the indigenous peoples politically. These efforts were also supported by leftist organizations from outside Mexico, especially to form unions of ejido organizations. These unions would later form the base of the EZLN organization.[45] One reason for the Church's efforts to reach out to the indigenous population was that starting in the 1970s, a shift began from traditional Catholic affiliation to Protestant, Evangelical and other Christian sects.[49] The 1980s saw a large wave of refugees coming into the state from Central America as a number of these countries, especially Guatemala, were in the midst of violent political turmoil. The Chiapas/Guatemala border had been relatively porous with people traveling back and forth easily in the 19th and 20th centuries, much like the Mexico/U.S. border around the same time. This is in spite of tensions caused by Mexico's annexation of the Soconusco region in the 19th century. The border between Mexico and Guatemala had been traditionally poorly guarded, due to diplomatic considerations, lack of resources and pressure from landowners who need cheap labor sources.[50] The arrival of thousands of refugees from Central America stressed Mexico's relationship with Guatemala, at one point coming close to war as well as a politically destabilized Chiapas. Although Mexico is not a signatory to the UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, international pressure forced the government to grant official protection to at least some of the refugees. Camps were established in Chiapas and other southern states, and mostly housed Mayan peoples. However, most Central American refugees from that time never received any official status, estimated by church and charity groups at about half a million from El Salvador alone.[51] The Mexican government resisted direct international intervention in the camps, but eventually relented somewhat because of finances.[52] By 1984, there were 92 camps with 46,000 refugees in Chiapas, concentrated in three areas, mostly near the Guatemalan border.[53] To make matters worse, the Guatemalan army conducted raids into camps on Mexican territories with significant casualties, terrifying the refugees and local populations.[54] From within Mexico, refugees faced threats by local governments who threatened to deport them, legally or not, and local paramilitary groups funded by those worried about the political situation in Central America spilling over into the state.[55] The official government response was to militarize the areas around the camps, which limited international access and migration into Mexico from Central America was restricted.[56] By 1990, it was estimated that there were over 200,000 Guatemalans and half a million from El Salvador, almost all peasant farmers and most under age twenty.[57] In the 1980s, the politization of the indigenous and rural populations of the state that began in the 1960s and 1970s continued. In 1980, several ejido (communal land organizations) joined to form the Union of Ejidal Unions and United Peasants of Chiapas, generally called the Union of Unions, or UU. It had a membership of 12,000 families from over 180 communities. By 1988, this organization joined with other to form the ARIC-Union of Unions (ARIC-UU) and took over much of the Lacandon Jungle portion of the state.[45] Most of the members of these organization were from Protestant and Evangelical sects as well as "Word of God" Catholics affiliated with the political movements of the Diocese of Chiapas. What they held in common was indigenous identity vis-à-vis the non-indigenous, using the old 19th century "caste war" word "Ladino" for them.[25][45][49] Economic liberalization and the EZLN   The adoption of liberal economic reforms by the Mexican federal government clashed with the leftist political ideals of these groups, notably as the reforms were believed to have begun to have negative economic effects on poor farmers, especially small-scale indigenous coffee-growers. Opposition would coalesce into the Zapatista movement in the 1990s.[45] Although the Zapatista movement couched its demands and cast its role in response to contemporary issues, especially in its opposition to neoliberalism, it operates in the tradition of a long line of peasant and indigenous uprisings that have occurred in the state since the colonial era. This is reflected in its indigenous vs. Mestizo character.[25][58] However, the movement was an economic one as well. Although the area has extensive resources, much of the local population of the state, especially in rural areas, did not benefit from this bounty. In the 1990s, two thirds of the state's residents did not have sewage service, only a third had electricity and half did not have potable water. Over half of the schools offered education only to the third grade and most pupils dropped out by the end of first grade.[55] Grievances, strongest in the San Cristóbal and Lacandon Jungle areas, were taken up by a small leftist guerrilla band led by a man called only "Subcomandante Marcos."[59] This small band, called the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, EZLN), came to the world's attention when on January 1, 1994 (the day the NAFTA treaty went into effect) EZLN forces occupied and took over the towns of San Cristobal de las Casas, Las Margaritas, Altamirano, Ocosingo and three others. They read their proclamation of revolt to the world and then laid siege to a nearby military base, capturing weapons and releasing many prisoners from the jails.[20] This action followed previous protests in the state in opposition to neoliberal economic policies.[60] Although it has been estimated[by whom?] as having no more than 300 armed guerrilla members, the EZLN paralyzed the Mexican government, which balked at the political risks of direct confrontation.[58] The major reason for this was that the rebellion caught the attention of the national and world press, as Marcos made full use of the then-new Internet to get the group's message out, putting the spotlight on indigenous issues in Mexico in general. Furthermore, the opposition press in Mexico City, especially La Jornada, actively supported the rebels. These factors encouraged the rebellion to go national.[61] Many[quantify] blamed the unrest on infiltration of leftists among the large Central American refugee population in Chiapas,[62] and the rebellion opened up splits in the countryside between those supporting and opposing the EZLN.[58] Zapatista sympathizers have included mostly Protestants and Word of God Catholics, opposing those "traditionalist" Catholics who practiced a syncretic form of Catholicism and indigenous beliefs. This split had existed in Chiapas since the 1970s, with the latter group supported by the caciques and others in the traditional power-structure. Protestants and Word of God Catholics (allied directly with the bishopric in San Cristóbal) tended to oppose traditional power structures.[60] The Bishop of Chiapas, Samuel Ruiz, and the Diocese of Chiapas reacted by offering to mediate between the rebels and authorities. However, because of this diocese's activism since the 1960s, authorities[which?] accused the clergy of being involved with the rebels.[63] There was some ambiguity about the relationship between Ruiz and Marcos and it was a constant feature of news coverage, with many in official circles using such to discredit Ruiz. Eventually, the activities of the Zapatistas began to worry the Roman Catholic Church in general and to upstage the diocese's attempts to re establish itself among Chiapan indigenous communities against Protestant evangelization. This would lead to a breach between the Church and the Zapatistas.[64] The Zapatista story remained in headlines for a number[quantify] of years. One reason for this was the December 1997 massacre of forty-five unarmed Tzotzil peasants, mostly women and children, by a government-backed paramilitary in the Zapatista-controlled village of Acteal in the Chenhaló municipality just north of San Cristóbal. This allowed many media outlets in Mexico to step up their criticisms of the government. Despite this, the armed conflict was brief, mostly because the Zapatistas, unlike many other guerilla movements, did not try to gain traditional political power. It focused more on trying to manipulate public opinion in order to obtain concessions from the government. This has linked the Zapatistas to other indigenous and identity-politics movements that arose in the late-20th century.[65] The main concession that the group received was the San Andrés Accords (1996), also known as the Law on Indian Rights and Culture.[21] The Accords appear to grant certain indigenous zones autonomy, but this is against the Mexican constitution,[citation needed] so its legitimacy has been questioned. Zapatista declarations since the mid-1990s have called for a new constitution.[66] As of 1999[update] the government had not found a solution to this problem.[58] The revolt also pressed the government to institute anti-poverty programs such as "Progresa" (later called "Oportunidades") and the "Puebla-Panama Plan" – aiming to increase trade between southern Mexico and Central America.[67] As of the first decade of the 2000s the Zapatista movement remained popular in many indigenous communities.[67] The uprising gave indigenous peoples a more active role in the state's politics.[15] However, it did not solve the economic issues that many peasant farmers face, especially the lack of land to cultivate. This problem has been at crisis proportions since the 1970s, and the government's reaction has been to encourage peasant farmers—mostly indigenous—to migrate into the sparsely populated Lacandon Jungle, a trend since earlier in the century.[58] From the 1970s on, some 100,000 people set up homes in this rainforest area, with many being recognized as ejidos, or communal land-holding organizations.[58] These migrants included Tzeltals, Tojolabals, Ch'ols and mestizos, mostly farming corn and beans and raising livestock. However, the government changed policies in the late 1980s with the establishment of the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, as much of the Lacandon Jungle had been destroyed or severely damaged.[31][68] While armed resistance has wound down, the Zapatistas have remained a strong political force, especially around San Cristóbal and the Lacandon Jungle, its traditional bases. Since the Accords, they have shifted focus in gaining autonomy for the communities they control.[19][69] Since the 1994 uprising, migration into the Lacandon Jungle has significantly increased, involving illegal settlements and cutting in the protected biosphere reserve. The Zapatistas support these actions as part of indigenous rights, but that has put them in conflict with international environmental groups and with the indigenous inhabitants of the rainforest area, the Lacandons. Environmental groups state that the settlements pose grave risks to what remains of the Lacandon, while the Zapatistas accuse them of being fronts for the government, which wants to open the rainforest up to multinational corporations.[68][70] Added to this is the possibility that significant oil and gas deposits exist under this area.[31] The Zapatista movement has had some successes. The agricultural sector of the economy now favors ejidos and other commonly-owned land.[15] There have been some other gains economically as well. In the last decades of the 20th century, Chiapas's traditional agricultural economy has diversified somewhat with the construction of more roads and better infrastructure by the federal and state governments. Tourism has become important in some areas of the state, especially in San Cristóbal de las Casas and Palenque.[71] Its economy is important to Mexico as a whole as well, producing coffee, corn, cacao, tobacco, sugar, fruit, vegetables and honey for export. It is also a key state for the nation's petrochemical and hydroelectric industries. A significant percentage of PEMEX's drilling and refining takes place in Chiapas and Tabasco, and Chiapas produces fifty-five percent of Mexico's hydroelectric energy.[55] However, Chiapas remains one of the poorest states in Mexico. Ninety-four of its 111 municipalities have a large percentage of the population living in poverty. In areas such as Ocosingo, Altamirano and Las Margaritas, the towns where the Zapatistas first came into prominence in 1994, 48% of the adults were illiterate.[72] Chiapas is still considered[by whom?] isolated and distant from the rest of Mexico, both culturally and geographically. It has significantly underdeveloped infrastructure compared to the rest of the country, and its significant indigenous population with isolationist tendencies keep the state distinct culturally.[71] Cultural stratification, neglect and lack of investment by the Mexican federal government has exacerbated this problem.[citation needed] Dissolution of the Rebel Zapatista Autonomous MunicipalitiesIn early November 2023, a treaty was signed by rebel Subcomandante Moises and EZLN that announced the dissolution of the Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities due to the cartel violence generated by Sinaloa Cartel and Jalisco New Generation Cartel and violent border clashes in Guatemala due to the increasing violence growing on the border.[73][74] Caracoles will remain open to locals but remain closed to outsiders, and the previous MAREZ system will be reorganized into a new autonomous system.[74] GeographyPolitical geographyChiapas is located in Southeastern Mexico, bordering the states of Tabasco, Veracruz and Oaxaca with the Pacific Ocean to the south and Guatemala to the east. It has a territory of 74,415 km2, the eighth largest state in Mexico. The state consists of 118 municipalities organized into nine political regions called Center, Altos, Fronteriza, Frailesca, Norte, Selva, Sierra, Soconusco and Istmo-Costa. There are 18 cities, twelve towns (villas) and 111 pueblos (villages).[75][76] Major cities include Tuxtla Gutiérrez, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Tapachula, Palenque, Comitán, and Chiapa de Corzo.[19][76] Geographical regions   The state has a complex geography with seven distinct regions according to the Mullerried classification system. These include the Pacific Coast Plains, the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, the Central Depression, the Central Highlands, the Eastern Mountains, the Northern Mountains and the Gulf Coast Plains. The Pacific Coast Plains is a strip of land parallel to the ocean. It is composed mostly of sediment from the mountains that border it on the northern side. It is uniformly flat, and stretches from the Bernal Mountain south to Tonalá. It has deep salty soils due to its proximity to the sea. It has mostly deciduous rainforest although most has been converted to pasture for cattle and fields for crops. It has numerous estuaries with mangroves and other aquatic vegetation.[77] The Sierra Madre de Chiapas runs parallel to the Pacific coastline of the state, northwest to southeast as a continuation of the Sierra Madre del Sur. This area has the highest altitudes in Chiapas including the Tacaná Volcano, which rises 4,093 m (13,428 ft) above sea level. Most of these mountains are volcanic in origin although the nucleus is metamorphic rock. It has a wide range of climates but little arable land. It is mostly covered in middle altitude rainforest, high altitude rainforest, and forests of oaks and pines.[77] The mountains partially block rain clouds from the Pacific, a process known as Orographic lift, which creates a particularly rich coastal region called the Soconusco.[78] The main commercial center of the sierra is the town of Motozintla, also near the Guatemalan border.[31] The Central Depression is in the center of the state. It is an extensive semi flat area bordered by the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, the Central Highlands and the Northern Mountains. Within the depression there are a number of distinct valleys. The climate here can be very hot and humid in the summer, especially due to the large volume of rain received in July and August. The original vegetation was lowland deciduous forest with some rainforest of middle altitudes and some oaks above 1,500 m (4,900 ft) above sea level.[77] The Central Highlands, also referred to as Los Altos, are mountains oriented from northwest to southeast with altitudes ranging from one thousand two hundred to one thousand six hundred m (3,900 to 5,200 ft) above sea level. The western highlands are displaced faults, while the eastern highlands are mainly folds of sedimentary formations – mainly limestone, shale, and sandstone.[31] These mountains, along the Sierra Madre of Chiapas become the Cuchumatanes where they extend over the border into Guatemala. Its topography is mountainous with many narrow valleys and karst formations called uvalas or poljés, depending on the size. Most of the rock is limestone allowing for a number of formations such as caves and sinkholes. There are also some isolated pockets of volcanic rock with the tallest peaks being the Tzontehuitz and Huitepec volcanos. There are no significant surface water systems as they are almost all underground. The original vegetation was forest of oak and pine but these have been heavily damaged.[77] The highlands climate in the Koeppen modified classification system for Mexico is humid temperate C(m) and subhumid temperate C (w 2 ) (w). This climate exhibits a summer rainy season and a dry winter, with possibilities of frost from December to March.[31] The Central Highlands have been the population center of Chiapas since the Conquest. European epidemics were hindered by the tierra fría climate, allowing the indigenous peoples in the highlands to retain their large numbers.[79] The Eastern Mountains (Montañas del Oriente) are in the east of the state, formed by various parallel mountain chains mostly made of limestone and sandstone. Its altitude varies from 500 to 1,500 m (1,600 to 4,900 ft). This area receives moisture from the Gulf of Mexico with abundant rainfall and exuberant vegetation, which creates the Lacandon Jungle, one of the most important rainforests in Mexico. The Northern Mountains (Montañas del Norte) are in the north of the state. They separate the flatlands of the Gulf Coast Plains from the Central Depression. Its rock is mostly limestone. These mountains also receive large amounts of rainfall with moisture from the Gulf of Mexico giving it a mostly hot and humid climate with rains year round. In the highest elevations around 1,800 m (5,900 ft), temperatures are somewhat cooler and do experience a winter. The terrain is rugged with small valleys whose natural vegetation is high altitude rainforest.[77] The Gulf Coast Plains (Llanura Costera del Golfo) stretch into Chiapas from the state of Tabasco, which gives it the alternate name of the Tabasqueña Plains. These plains are found only in the extreme north of the state. The terrain is flat and prone to flooding during the rainy season as it was built by sediments deposited by rivers and streams heading to the Gulf.[77] Lacandon Jungle The Lacandon Jungle is situated in north eastern Chiapas, centered on a series of canyonlike valleys called the Cañadas, between smaller mountain ridges oriented from northwest to southeast.[31][80] The ecosystem covers an area of approximately 1.9×106 ha (4.7×106 acres) extending from Chiapas into northern Guatemala and southern Yucatán Peninsula and into Belize. This area contains as much as 25% of Mexico's total species diversity,[81] most of which has not been researched.[82] It has a predominantly hot and humid climate (Am w" i g) with most rain falling from summer to part of fall, with an average of between 2300 and 2600 mm per year. There is a short dry season from March to May. The predominant wild vegetation is perennial high rainforest.[80] The Lacandon comprises a biosphere reserve (Montes Azules); four natural protected areas (Bonampak, Yaxchilan, Chan Kin, and Lacantum); and the communal reserve (La Cojolita), which functions as a biological corridor with the area of Petén in Guatemala. Flowing within the Rainforest is the Usumacinta River, considered to be one of the largest rivers in Mexico and seventh largest in the world based on volume of water.[83][dubious – discuss]  During the 20th century, the Lacandon has had a dramatic increase in population and along with it, severe deforestation. The population of municipalities in this area, Altamirano, Las Margaritas, Ocosingo and Palenque have risen from 11,000 in 1920 to over 376,000 in 2000.[46] Migrants include Ch'ol, Tzeltal, Tzotzil, Tojolabal indigenous peoples along with mestizos, Guatemalan refugees and others.[84] Most of these migrants are peasant farmers, who cut forest to plant crops. However, the soil of this area cannot support annual crop farming for more than three or four harvests.[31] The increase in population and the need to move on to new lands has pitted migrants against each other, the native Lacandon people, and the various ecological reserves for land.[68][70][84] It is estimated that only ten percent of the original Lacandon rainforest in Mexico remains, with the rest strip-mined, logged and farmed. It once stretched over a large part of eastern Chiapas but all that remains is along the northern edge of the Guatemalan border.[85] Of this remaining portion, Mexico is losing over five percent each year.[86]  The best preserved portion of the Lacandon is within the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve.[87] It is centered on what was a commercial logging grant by the Porfirio Díaz government, which the government later nationalized. However, this nationalization and conversion into a reserve has made it one of the most contested lands in Chiapas, with the already existing ejidos and other settlements within the park along with new arrivals squatting on the land.[31][68] Soconusco The Soconusco region encompasses a coastal plain and a mountain range with elevations of up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) above sea levels paralleling the Pacific Coast.[31][88] The highest peak in Chiapas is the Tacaná Volcano at 4,060 m (13,320 ft) above sea level.[89] In accordance with an 1882 treaty, the dividing line between Mexico and Guatemala goes right over the summit of this volcano.[82] The climate is tropical, with a number of rivers and evergreen forests in the mountains. This is Chiapas's major coffee-producing area, as it has the best soils and climate for coffee.[31] Before the arrival of the Spanish, this area was the principal source of cocoa seeds in the Aztec empire, which they used as currency, and for the highly prized quetzal feathers used by the nobility. It would become the first area to produce coffee, introduced by an Italian entrepreneur on the La Chacara farm.[31] Coffee is cultivated on the slopes of these mountains mostly between 600 and 1,200 m (2,000 and 3,900 ft) asl. Mexico produces about 4 million sacks of green coffee each year, fifth in the world behind Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia and Vietnam. Most producers are small with plots of land under five ha (12 acres). From November to January, the annual crop is harvested and processed employing thousands of seasonal workers. Lately, a number of coffee haciendas have been developing tourism infrastructure as well.[88] Environment and protected areas   Chiapas is located in the tropical belt of the planet, but the climate is moderated in many areas by altitude. For this reason, there are hot, semi-hot, temperate and even cold climates. Some areas have abundant rainfall year-round and others receive most of their rain between May and October, with a dry season from November to April. The mountain areas affect wind and moisture flow over the state, concentrating moisture in certain areas of the state. They also are responsible for some cloud-covered rainforest areas in the Sierra Madre.[77] Chiapas's rainforests are home to thousands of animals and plants, some of which cannot be found anywhere else in the world.[19] Natural vegetation varies from lowland to highland tropical forest, pine and oak forests in the highest altitudes and plains area with some grassland. Chiapas is ranked second in forest resources in Mexico with valued woods such as pine, cypress, Liquidambar, oak, cedar, mahogany and more. The Lacandon Jungle is one of the last major tropical rainforests in the northern hemisphere with an extension of 600,000 ha (1,500,000 acres). It contains about sixty percent of Mexico's tropical tree species, 3,500 species of plants, 1,157 species of invertebrates and over 500 of vertebrate species. Chiapas has one of the greatest diversities in wildlife in the Americas. There are more than 100 species of amphibians, 700 species of birds, fifty of mammals and just over 200 species of reptiles. In the hot lowlands, there are armadillos, monkeys, pelicans, wild boar, jaguars, crocodiles, iguanas and many others. In the temperate regions there are species such as bobcats, salamanders, a large red lizard Abronia lythrochila, weasels, opossums, deer, ocelots and bats. The coastal areas have large quantities of fish, turtles, and crustaceans, with many species in danger of extinction or endangered as they are endemic only to this area. The total biodiversity of the state is estimated at over 50,000 species of plants and animals. The diversity of species is not limited to the hot lowlands. The higher altitudes also have mesophile forests, oak/pine forests in the Los Altos, Northern Mountains and Sierra Madre and the extensive estuaries and mangrove wetlands along the coast.[77] Chiapas has about thirty percent of Mexico's fresh water resources. The Sierra Madre divides them into those that flow to the Pacific and those that flow to the Gulf of Mexico. Most of the first are short rivers and streams; most longer ones flow to the Gulf. Most Pacific side rivers do not drain directly into this ocean but into lagoons and estuaries. The two largest rivers are the Grijalva and the Usumacinta, with both part of the same system. The Grijalva has four dams built on it the Belisario Dominguez (La Angostura); Manuel Moreno Torres (Chicoasén); Nezahualcóyotl (Malpaso); and Angel Albino Corzo (Peñitas). The Usumacinta divides the state from Guatemala and is the longest river in Central America. In total, the state has 110,000 ha (270,000 acres) of surface waters, 260 km (160 mi) of coastline, control of 96,000 km2 (37,000 sq mi) of ocean, 75,230 ha (185,900 acres) of estuaries and ten lake systems.[77] Laguna Miramar is a lake in the Montes Azules reserve and the largest in the Lacandon Jungle at 40 km in diameter. The color of its waters varies from indigo to emerald green and in ancient times, there were settlements on its islands and its caves on the shoreline. The Catazajá Lake is 28 km north of the city of Palenque. It is formed by rainwater captured as it makes its way to the Usumacinta River. It contains wildlife such as manatees and iguanas and it is surrounded by rainforest. Fishing on this lake is an ancient tradition and the lake has an annual bass fishing tournament. The Welib Já Waterfall is located on the road between Palenque and Bonampak.[87]  The state has thirty-six protected areas at the state and federal levels along with 67 areas protected by various municipalities. The Sumidero Canyon National Park was decreed in 1980 with an extension of 21,789 ha (53,840 acres). It extends over two of the regions of the state, the Central Depression and the Central Highlands over the municipalities of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Nuevo Usumacinta, Chiapa de Corzo and San Fernando. The canyon has steep and vertical sides that rise to up to 1000 meters from the river below with mostly tropical rainforest but some areas with xerophile vegetation such as cactus can be found. The river below, which has cut the canyon over the course of twelve million years, is called the Grijalva. The canyon is emblematic for the state as it is featured in the state seal.[77][90] The Sumidero Canyon was once the site of a battle between the Spaniards and Chiapanecan Indians. Many Chiapanecans chose to throw themselves from the high edges of the canyon rather than be defeated by Spanish forces. Today, the canyon is a popular destination for ecotourism. Visitors can take boat trips down the river that runs through the canyon and see the area's many birds and abundant vegetation.[19] The Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve was decreed in 1978. It is located in the northeast of the state in the Lacandon Jungle. It covers 331,200 ha (818,000 acres) in the municipalities of Maravilla Tenejapa, Ocosingo and Las Margaritas. It conserves highland perennial rainforest. The jungle is in the Usumacinta River basin east of the Chiapas Highlands. It is recognized by the United Nations Environment Programme for its global biological and cultural significance. In 1992, the 61,874 ha (152,890-acre) Lacantun Reserve, which includes the Classic Maya archaeological sites of Yaxchilan and Bonampak, was added to the biosphere reserve.[70][77] Agua Azul Waterfall Protection Area is in the Northern Mountains in the municipality of Tumbalá. It covers an area of 2,580 ha (6,400 acres) of rainforest and pine-oak forest, centered on the waterfalls it is named after.[77] It is located in an area locally called the "Mountains of Water", as many rivers flow through there on their way to the Gulf of Mexico. The rugged terrain encourages waterfalls with large pools at the bottom, that the falling water has carved into the sedimentary rock and limestone. Agua Azul is one of the best known in the state. The waters of the Agua Azul River emerge from a cave that forms a natural bridge of thirty meters and five small waterfalls in succession, all with pools of water at the bottom. In addition to Agua Azul, the area has other attractions—such as the Shumuljá River, which contains rapids and waterfalls, the Misol Há Waterfall with a thirty-meter drop, the Bolón Ajau Waterfall with a fourteen-meter drop, the Gallito Copetón rapids, the Blacquiazules Waterfalls, and a section of calm water called the Agua Clara.[91] The El Ocote Biosphere Reserve was decreed in 1982 located in the Northern Mountains at the boundary with the Sierra Madre del Sur in the municipalities of Ocozocoautla, Cintalapa and Tecpatán. It has a surface area of 101,288.15 ha (250,288.5 acres) and preserves a rainforest area with karst formations. The Lagunas de Montebello National Park was decreed in 1959 and consists of 7,371 ha (18,210 acres) near the Guatemalan border in the municipalities of La Independencia and La Trinitaria. It contains two of the most threatened ecosystems in Mexico the "cloud rainforest" and the Soconusco rainforest. The El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve, decreed in 1990, is located in the Sierra Madre de Chiapas in the municipalities of Acacoyagua, Ángel Albino Corzo, Montecristo de Guerrero, La Concordia, Mapastepec, Pijijiapan, Siltepec and Villa Corzo near the Pacific Ocean with 119,177.29 ha (294,493.5 acres). It conserves areas of tropical rainforest and many freshwater systems endemic to Central America.[77] It is home to around 400 species of birds including several rare species such as the horned guan, the quetzal and the azure-rumped tanager.[19] The Palenque National Forest is centered on the archaeological site of the same name and was decreed in 1981. It is located in the municipality of Palenque where the Northern Mountains meet the Gulf Coast Plain. It extends over 1,381 ha (3,410 acres) of tropical rainforest. The Laguna Bélgica Conservation Zone is located in the north west of the state in the municipality of Ocozocoautla. It covers forty-two hectares centered on the Bélgica Lake. The El Zapotal Ecological Center was established in 1980.[77] Nahá–Metzabok is an area in the Lacandon Forest whose name means "place of the black lord" in Nahuatl. It extends over 617.49 km2 (238.41 sq mi) and in 2010, it was included in the World Network of Biosphere Reserves. Two main communities in the area are called Nahá and Metzabok. They were established in the 1940s, but the oldest communities in the area belong to the Lacandon people. The area has large numbers of wildlife including endangered species such as eagles, quetzals and jaguars.[92] DemographicsLargest cities

General statistics