|

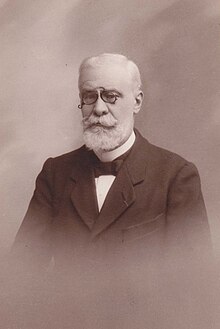

Charles Janet

Charles Janet (French: [ʃaʁl ʒanɛ]; 15 June 1849 – 7 February 1932) was a French engineer, company director, inventor and biologist. He is also known for his left-step periodic table of chemical elements.[3] Life and workJanet graduated from the École Centrale Paris in 1872,[1]: 57 and worked for some years as a chemist and engineer in a few factories in Puteaux (1872), Rouen (1873–74), and Saint-Ouen (1875–76).[1]: 61–65 He was then employed by Philippe Alphonse Dupont, at Société A. Dupont & Cie, a factory that produced bone buttons and fine brushes. He married Berthe Marie Antonia Dupont, the daughter of the owner, in November 1877, and worked there for the rest of his life, finding time for research in various branches of science.[1] Janet's collection of 50,000 fossils and other specimens was dispersed after his death.[2][4] His studies of the morphology of the heads of ants, wasps and bees, and his micrographs were of remarkable quality.[5] He also worked on plant biology and wrote a series of papers on evolution. He was an inventor and designed much of his own equipment, including the formicarium, in which an ant colony is made visible by being formed between two glass panes.[6] In 1927 he turned his attention to the periodic table and wrote a series of six articles in French that were privately printed and never widely circulated. His only article in English was poorly edited and gave a confused idea of his thinking.[7] Scientific workIn parallel with his professional activities, Janet began a university course at the Sorbonne in 1886. He became a member of the French Entomological Society and the French Zoological Society. First in his class, he began a thesis on ants and obtained his doctorate in natural sciences in 1900. Before the end of his studies, the French Academy of Sciences regularly published his research in its reports and awarded him the Thore Prize in 1896.[8][9] In 1899, he was elected president of the French Zoological Society. In 1900, he improved his artificial nests and showed them at the Universal Exhibition in Paris.[10] He attracted the interest of journalists who described the public's interest in ants. In 1909, the French Academy of Sciences awarded him the Cuvier Prize[11] for his work in zoology. Geology and paleontologyJanet explored the Paris Basin and especially its chalk.[12] At the request of Edmond Hébert and his geology laboratory at the École Pratique des Hautes Études, he organized a geological excursion[13] around Beauvais for the students of the Sorbonne University and the MNHN. He assembled a collection of fossil and prehistoric pieces. He estimated it contained around 50,000 items.[2] A large part of the collection included fossils from regional deposits that have now disappeared or are almost inaccessible, such as the Bracheux Sands (partially covered by the expansion of the city of Beauvais). He also developed a method for preserving the fragile shells of these geological layers.[14] Other local tertiary deposits are represented, such as the Ypresian and Lutetian from the regions of Chaumont-en-Vexin, Parnes, Grignon, Chambors, and Mouy. The collection also included numerous echinoderms, for which he co-wrote an article with Lucien Cuénot.[15] In the chalk of the Beauvais area, he discovered three new species of belemnites.[16] These are Actinocamax grossouvrei, Actinocamax toucasi, and Actinocamax alfridi.[17] Entomology Janet was particularly interested in social hymenoptera. In 1894, he observed a hornet's nest from its origin until the death of the last worker.[18] During these 5 months of observations, he discovered the trophallaxis of hornet larvae.[19][20] He invented a vertical artificial nest that remained a tool for entomologists for a long time. This type of nest allowed him to understand how some insects live at the expense of ants. He surprised, for example, the silverfish stealing the droplet of sugary liquid exchanged between two ants.[21] He then performed in-depth studies on the internal anatomy of ants, where he endeavored to show their organization in metameres.[22] In the young ant queen, he discovered the transformation of flight muscles after she tore off her wings. He demonstrated that these muscles evolve into lipid cells, providing the necessary energy for this queen who does not feed during the long months it takes to establish her colony.[23] In the end, 22 of the 24 notes he proposed to the French Academy of Sciences were related to social insects. He gradually sought to link ethology with insect physiology through histological sections.[5] Maurice Maeterlinck wrote:

BotanyBuilding on his studies of insect metamerism, Janet sought to conceive a common ancestor for animals and plants. According to Janet, metazoans came from colonies of flagellated protozoa. Janet studied Volvoxs. For him, the Volvox,[25] which has not evolved since its divergence from phyto-flagellates, is a living fossil that strongly recalls the beginnings of the animal kingdom.  A few years later, a theory called orthobiontics[26] emerged in which Janet outlined an organization plan for living beings. Ultimately based on excessive theorization that takes precedence over his observations, undermined by a text filled with complex neologisms, all translated into mathematical language, this theory remained inaccessible. It was also extremely poorly received in the Revue générale des Sciences pures et appliquées (General Review of Pure and Applied Sciences).[27] Chemistry At the age of 78, Janet began to research atoms. He was interested in the properties of atoms and the organization of their nuclei. To synthesize his ideas, he reflected on a periodic classification of atomic elements.[28] For him, their physico-chemical properties are intimately linked to their arithmetic and graphical arrangement.[29] Moreover, the perfect regularity he observes at all levels of his table is, for Janet, proof that he has discovered the correct distribution law. In 1930, he even proposes to verify it by aligning his classification with the very recent quantum theory.[30] In doing so, he is the first to state the rule that describes the order in which electrons fill the subshells of an atom. This rule, later rediscovered, is commonly called the Madelung rule since 1936 among English speakers or the Klechkowski rule (of Soviet origin in 1962 and in use in France). Confidentially, Janet's classification will remain completely ignored in France. Thanks to these astonishing spiral figures, it will reappear 40 years later among American chemists[31] before a new eclipse. It has only been considered a valid alternative[32] to the famous Mendeleev's classification under the name of Left Step Table for about a decade. Eric Scerri, an American historian (UCLA), has popularized Janet's form in magazines such as Scientific American[33] or Pour la Science.[34] He also devotes an entire chapter of his latest work[35] to Charles Janet, whom he sees as a minor contributor in terms of fame, but major in terms of ideas. Periodic tableJanet started from the fact that the series of chemical elements is a continuous sequence, which he represented as a helix traced on the surfaces of four nested cylinders. By various geometrical transformations he derived several striking designs, one of which is his "left-step periodic table", in which hydrogen and helium are placed above lithium and beryllium. It was only later that he realized that his arrangement agreed perfectly with quantum theory and the electronic structure of the atom. He placed the actinides under the lanthanides twenty years before Glenn Seaborg, and he continued the series to element 120. Janet's table differs from the standard table in placing the s-block elements on the right, so that the subshells of the periodic table are arranged in the order (n − 3)f, (n − 2)d, (n − 1)p, ns, from left to right. There is then no need to interrupt the sequence or move the f block into a 'footnote'. He believed that no elements heavier than number 120 would be found, so he did not envisage a g block. In terms of atomic quantum numbers, each row corresponds to one value of the sum (n + ℓ) where n is the principal quantum number and ℓ the azimuthal quantum number. The table therefore corresponds to the Madelung rule, which states that atomic subshells are filled in the order of increasing values of (n + ℓ). The philosopher of chemistry Eric Scerri has written extensively in favor of Janet's left-step periodic table, and it is being increasingly discussed as a candidate for the optimal or most fundamental form of the periodic table.[36]

Janet also envisaged an element zero whose 'atom' would consist of two neutrons,[37] and he speculated that this would be the link to a mirror-image table of elements with negative atomic numbers – in effect anti-matter. He also conceived of heavy hydrogen (deuterium). He died just before the discovery of the neutron, the positron and heavy hydrogen.[3] His work was championed most notably by Edward G. Mazurs.[31] FamilyArmand Janet,[38]: 5 Charles's brother was also an engineer and entomologist. Armand became known as a lepidopterist[5] and was president of the Société entomologique de France in 1911.[38] References

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia