|

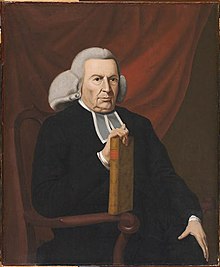

Charles Chauncy (1705–1787)

Charles Chauncy (1 January 1705 – 10 February 1787) was an American Congregational clergyman. He is known for his opposition to the First Great Awakening and his contributions to the development of Unitarianism and Liberal Protestantism, particularly his insistence on rational religion and defense of universal salvation. Life and career Chauncy was born into the elite Puritan merchant class that ruled Boston, Massachusetts. His great-grandfather, Charles Chauncy, after whom he was named, was the second president of Harvard College. His father was a successful Boston merchant. Chauncy was educated at the Boston Latin School and at Harvard, where he received both his undergraduate degree and his master's in theology. In 1727, Chauncy was ordained as an assistant minister of Boston's First Church, the oldest Congregational church in the city and one of the most important in New England. In 1762, Chauncy became pastor of First Church. He served the congregation for 60 years until his death.[1][2] Chauncy was an opponent of the First Great Awakening, which split the Congregational churches between Old Light and New Light factions. As a leader of the Old Lights, Chauncy spoke out against religious enthusiasm stirred up by revival preachers. Chauncy's fame would establish him as the chief defender of New England orthodoxy throughout the eighteenth century. He led the opposition against appointing an Anglican bishop for the American colonies. During the American Revolution, he famously supported the Patriot cause through sermons and pamphlets, to the point that he was seen as incendiary and dangerous to British efforts as Samuel Adams and other famous Patriots. [2][1] He earned the title "patriot preacher" given to him by King George and his work during the Revolution makes him the key "theologian of the American Revolution".[3] Chauncy was a charter member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1780) and was granted an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree from the University of Edinburgh. He was recognized by the Massachusetts Historical Society (when his portrait was hung there) as "eminent for his talents, learning, and lover of liberty, civil and religious."[1] TheologyDespite his Puritan heritage, Chauncy opposed Calvinism and its doctrine of total depravity. He held liberal Arminian views on free will, believing that human beings have God-given "natural powers" that were meant to be nurtured toward "an actual likeness to God in knowledge, righteousness, and true holiness".[4] Chauncy and fellow liberal Congregationalists Jonathan Mayhew and Ebenezer Gay were influenced by Enlightenment thought. They called for a "supernatural rationalism" that affirmed both reason and divine revelation as contained in the Bible.[5] The traditional view among scholars has been that Chauncy deviated from orthodox Trinitarian theology and that his Christology was Arian. Norman and Lee Gibbs, however, argue that Chauncy's views have been misunderstood and misrepresented.[6] They argue Chauncy's theology was Trinitarian, not Arian, and that he had a kenotic theology in regards to the Incarnation.[7] Sometime in the 1750s, Chauncy underwent a thorough scriptural study of Romans and Genesis, coming to the conclusion that all of humanity was destined for eternal salvation. He based this argument on the perfect equivalence between Adam's downfall and Jesus' salvific work. As early as 1754, he began circulating his views among local ministers. By the 1780s the manuscript, which he had coded as "pudding" had circulated among American clergy like Ezra Stiles and correspondents in London like minister Richard Price. In 1782, Chauncy finally decided to publish his views. There were likely two incidents that prompted his publication: 1) Baptist minister Isaac Backus recently published a text decrying the spread of universal salvation across the New England countryside with the itinerancy of universalist ministers John Murray and Elhanan Winchester, and the ever opportunistic Chauncy wanted an opportunity to publicly correct his theological opponent, and 2) the spread of universal salvation required Chauncy to clarify how his own views differed from those promulgated by Murray and Winchester. Given it was difficult to publish in Boston due to the American Revolution, Chauncy pursued a shorter publication titled "Salvation of All Men" which his peers lambasted. He would eventually publish "The Mystery Hid from Ages and Generations" in London to appease critics of his original piece. He followed it up with various other prooftexts including "Benevolence of the Deity" and "Five Dissertations." While initially controversial, his three works were generally received by Boston's clerical and political elite, including diplomat John Adams.[8] Chauncy's life and legacy reflects the theological transformations of eighteenth-century New England. He captures the all-too American contradiction between theological liberalism and social conservatism, which would shape the development of the American Unitarian tradition and Liberal Protestantism.[1] Works

References

Further reading

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia