|

Chancellorship of George Osborne

George Osborne served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from May 2010 to July 2016 in the David Cameron–Nick Clegg coalition Conservative-Liberal Democrat government and the David Cameron majority Conservative government. His tenure pursued austerity policies aimed at reducing the budget deficit and launched the Northern Powerhouse initiative. He had previously served as Shadow Chancellor in the Shadow Cabinet of David Cameron from 2005 to 2010. Following the 2010 general election, negotiations led to David Cameron becoming prime minister as the head of a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats. Osborne was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Cameron–Clegg coalition. He succeeded Alistair Darling, inheriting a large deficit in government finances due to the effects of the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession. At age 39, Osborne became the youngest Chancellor of the Exchequer since the appointment of Randolph Churchill over 120 years prior at age 37.[1] As Chancellor, Osborne pursued austerity policies aimed at reducing the budget deficit and launched the Northern Powerhouse initiative. After the Conservatives won an overall majority in the 2015 general election, Cameron reappointed Osbourne as Chancellor in his second government and gave him the additional title of First Secretary of State. He was widely viewed as a potential successor to David Cameron as Leader of the Conservative Party; one Conservative MP, Nadhim Zahawi, suggested that the closeness of his relationship with Cameron meant that the two effectively shared power during the duration of the Cameron governments. Following the 2016 referendum vote to leave the European Union and Cameron's consequent resignation, he was dismissed by Cameron's successor Theresa May. He was succeeded by Philip Hammond. The austerity measures are generally now viewed as having failed to reduce unemployment, lower interest rates, or stimulate growth, and have been linked to worsened inequality and poverty and a rise in political instability. Cameron–Clegg coalition2010Osborne was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer on 11 May 2010, and was sworn in as a Privy Counsellor two days later.[2] Osborne acceded to the chancellorship in the continuing wake of the financial crisis. Two of his first acts were setting up the Office for Budget Responsibility and commissioning a government-wide spending review, which was to conclude in autumn 2010 and to set limits on departmental spending until 2014–15.[3] Shortly before the 2010 election, Osborne had pledged to be "tougher than Thatcher" on Britain's budget deficit,[4] and he duly set himself the target of reducing the UK's deficit to the point that, in the financial year 2015–16, total public debt would be falling as a proportion of GDP.[5] On 24 May 2010, Osborne outlined £6.2bn cuts: "We simply cannot afford to increase public debt at the rate of £3bn each week."[6] Documents leaked from the Treasury the following month revealed that Osborne anticipated his tighter spending would lead to 1.3 million jobs being lost over the course of the parliament.[7] Osborne termed those who objected to his policy "deficit-deniers".[8] In July 2010, whilst seeking cuts of up to 25 per cent in government spending to tackle the deficit, Osborne insisted the £20 billion cost of building four new Vanguard-class submarines to bear Trident missiles had to be considered as part of the Ministry of Defence's core funding, even if that implied a severe reduction in the rest of the Ministry's budget. Liam Fox, the Secretary of State for Defence, warned that if Trident were to be considered core funding, there would have to be severe restrictions in the way that the UK operated militarily.[9] Osborne presented the Government's Spending Review on 20 October, which fixed spending budgets for each government department up to 2014–15.[10][11] Before and after becoming Chancellor, Osborne had alleged that the UK was on "the verge of bankruptcy",[12][13] though this assertion was criticised by the Treasury Select Committee and others as an effort to try and justify his programme of spending cuts.[14][15] On 4 October 2010, in a speech at the Conservative conference in Birmingham, Osborne announced a cap on the overall amount of benefits a family can receive from the state, estimated to be around £500 a week from 2013. It was estimated that this could result in 50,000 unemployed families losing an average of £93 a week. He also announced that he would end the universal entitlement to child benefit, and that from 2013 the entitlement would be removed from people paying the 40% and 50% income tax rates.[16] 2011 In February 2011 Osborne announced Project Merlin, whereby banks aimed to lend about £190bn to businesses in 2011 (including £76bn to small firms), curb bonuses and reveal some salary details of their top earners; meanwhile, the bank levy would increase by £800m. Liberal Democrat Treasury spokesman Lord Oakeshott resigned after the agreement was announced. Other pledges included providing £200m of capital for David Cameron's Big Society Bank, which was supposed to finance community projects.[17] In November 2011, Osborne sold Northern Rock to Richard Branson's Virgin Money for a price that was to range from £747m to £1bn.[18] Northern Rock, the first British bank in 150 years to suffer a bank run, had been taken into public ownership in 2008, then divided into two entities on 1 January 2010 – the other half being Northern Rock (Asset Management) plc.[19] The Independent described the entity sold as the "detoxified arm" of the bank, while saying the taxpayers retained "responsibility for £20bn of toxic assets such as bad debts and closed mortgages". The deal valued the bank at somewhat less than its £1.12bn net asset value, and "locks in a minimum loss" for taxpayers of £373m to £453m.[20] Osborne argued the deal would get "more money back than any other deal on the table".[18] and responded to concerns about the timing by saying that a secret deal between the previous Labour government and the European Commission in Brussels obliged them to sell the bank in or before 2013, and "[g]iven we were advised that Northern Rock plc would have been likely to remain loss-making [until] at least well into 2012, which would have depleted taxpayer resources still further, agreeing a sale now was even more imperative."[20] Osborne's 2011 Autumn Statement was delivered to Parliament on 29 November 2011. It included a programme of supply-side economic reforms such as investments in infrastructure intended to support economic growth.[21] 2012The 2012 budget – dubbed the "omnishambles budget" by the then Labour leader Ed Miliband – is viewed as the nadir of Osborne's political fortunes.[22][23] Osborne cut the 50% income tax rate on top earners, which he said had been specially designated by his predecessor as "temporary", to 45%. Figures from Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs showed that the amount of additional-rate tax paid had increased under the new rate from £38 billion in 2012/13 to £46 billion in 2013/14, which Osborne said was caused by the new rate being more "competitive".[24] Osborne faced criticism for simultaneously proposing imposing Value-added tax (VAT) on food such as Cornish pasties when served at above-ambient temperature. Critics commented on the potential effect on vendors, with members of the Treasury Select Committee suggesting that Osborne was inexperienced with the issue after a comment that he 'couldn't remember' the last time he had bought such a pasty from Greggs.[25] The "pasty tax" proposal was later withdrawn in what was seen as a political "U-turn",[26] as were proposals to cut tax relief on charitable donations and to tax static caravans.[27] In October 2012, Osborne proposed a new policy to boost the hiring of staff, under which companies would be able to give new appointees shares worth between £2,000 and £50,000, but the appointees would lose the right to claim unfair dismissal and time off for training.[28][29] Osborne sent a letter in 2012 to Ben Bernanke, the chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, in an attempt to help HSBC's leadership avoid criminal charges over the bank's involvement in laundering drug money and in channelling money to countries under economic sanctions.[30] Osborne suggested that if HSBC were to lose its banking license in the U.S., this could have negative consequences for the financial markets in Europe and Asia. HSBC avoided criminal charges, and settled with the U.S. Department of Justice for $1.92 bn.[30] Budget deficit In February 2013, the UK lost its AAA credit rating—which Osborne had indicated to be a priority when coming to power—for the first time since 1978.[31] His March 2013 budget was made when the Office for Budget Responsibility had halved its forecast for that year's economic growth from 1.2% to 0.6%.[32] It was described by The Daily Telegraph's economics editor as "an inventive, scattergun approach to growth that half-ticked the demands of every policy commentator, wrapped together under the Chancellor's banner of Britain as an 'aspiration nation'."[33] However, it was positively received by the public, with the ensuing boost to Conservative Party support in opinion polls standing in marked contrast to the previous year's budget.[34] The economy subsequently began to pick up in mid-2013, with Osborne's net public approval rating rising from −33 to +3 over the following 12 months.[22]

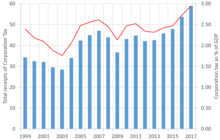

The Conservative manifesto for the 2015 general election contained a promise not to raise income tax, VAT, or National Insurance for the duration of the parliament. Journalist George Eaton maintains that Osborne did not expect an outright Conservative majority, and expected his Liberal Democrat coalition partners to make him break that promise.[38] Cameron majority governmentAfter the Conservatives won an overall majority at the 2015 general election, Osborne was reappointed Chancellor of the Exchequer by Cameron in his second government. Osborne was also appointed First Secretary of State,[39][40] replacing the retiring William Hague. July 2015 budgetOsborne announced on 16 May that he would deliver a second Budget on 8 July, and promised action on tax avoidance by the rich by bringing in a "Google tax" designed to discourage large companies diverting profits out of the UK to avoid tax.[41] In addition, large companies would now have to publish their UK tax strategies; any large businesses that persistently engaged in aggressive tax planning would be subject to special measures.[42] However, comments made by Osborne in 2003 on BBC Two's Daily Politics programme then resurfaced; these regarded the avoidance of inheritance tax and using "clever financial products" to pass the value of homeowners' properties to their children, and were widely criticised by politicians and journalists as hypocritical.[43][44] The second Budget also increased funding for the National Health Service, more apprenticeships, efforts to increase productivity and cuts to the welfare budget.[45] In response, the Conservative-led Local Government Association, on behalf of 375 Conservative-, Labour- and Liberal Democrat-run councils, said that further austerity measures were "not an option" as they would "devastate" local services. They said that local councils had already had to make cuts of 40% since 2010 and couldn't make any more cuts without serious consequences for the most vulnerable.[46] After the budget, many departments were told to work out the effect on services of spending cuts from 25% to 40% by 2019–20. This prompted fears that services the public takes for granted could be hit,[47] and concern that the Conservative Party had not explained the policy clearly in its manifesto before the 2015 election.[48] Osborne announced the introduction of a "National Living Wage" of £7.20/hour, rising to £9/hour by 2020, which would apply to those aged 25 or over.[49] This was widely cheered by both Conservative MPs and political commentators.[50] He also announced a raise in the income tax personal allowance to £11,000;[51] measures to introduce tax incentives for large corporations to create apprenticeships, aiming for 3 million new apprenticeships by 2020; and a cut in the benefits cap to £23,000 in London and £20,000 in the rest of the country.[51] The July budget postponed the predicted arrival of a UK surplus from 2019 to 2020, and included an extra £18 billion more borrowing for 2016–20 than planned for the same period in March.[52] In the July Budget, Osborne also planned to cut tax credits, which top up pay for low-income workers, prompting claims that this represented a breach of promises made by colleagues before the general election in May.[53] Following public opposition and a House of Lords vote against the changes, Osborne scrapped these changes in the 2015 Autumn Statement, saying that higher-than-expected tax receipts gave him more room for manoeuvre.[54] The Institute for Fiscal Studies noted that Osborne's proposals implied that tax credits would still be cut as part of the switch to Universal Credit in 2018.[53] FCAIn July 2015, Osborne was criticised by John Mann of the Treasury Select Committee for ending the contract of Martin Wheatley, head of the Financial Conduct Authority, and undermining the independence of the regulator. Wheatley had angered the banks by cracking down on misselling following the payment protection insurance scandal and fining them £1.4B.[55] Osborne was also criticised over his perceived inaction on enacting policies set forth by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to combat tax avoidance.[56] MPs called for an inquiry in January 2016, when it was revealed that a retrospective tax deal the Treasury agreed with Google over previous diverted profits allowed it to pay an effective tax rate of just 3% over the previous decade.[57] BBC licence feeAccording to The Guardian, Osborne was "the driving force" behind the BBC licence fee agreement which saw the BBC responsible for funding the £700m welfare cost of free TV licences for the over-75s, meaning that it lost almost 20% of its income.[58] The Guardian also noted Osborne's four meetings with News Corp representatives and two meetings with Rupert Murdoch before the deal was announced.[59] Hinkley Point CGeorge Osborne strongly supported China's involvement in sensitive sectors such as the Hinkley Point C nuclear power station. The then Home Secretary Theresa May had been unhappy about Osborne's "Gung ho" attitude to the Chinese, and had objected to the project. It has been delayed for final approval after May assumed the Prime Ministership. In 2015, May's political adviser Nick Timothy expressed his worry that China was effectively buying Britain's silence on allegations of Chinese human rights abuse, and criticised David Cameron and Osborne for "selling our national security to China" without rational concerns and "the Government seems intent on ignoring the evidence and presumably the advice of the security and intelligence agencies." He warned that the Chinese could use their role in the programme (designing and constructing nuclear reactors) to build weaknesses into computer systems which allow them to shut down Britain's energy production at will and "...no amount of trade and investment should justify allowing a hostile state easy access to the country's critical national infrastructure."[60][61][62] 2016 budget In Osborne's 2016 budget he introduced a sugar tax and raised the tax-free allowance for income tax to £11,500, as well as lifting the 40% income tax threshold to £45,000. He also gave initial funding for several large infrastructure projects, such as High Speed 3 (an east–west rail line across the north of England), Crossrail 2 (a north–south rail line across London), a road tunnel across the Pennines, and upgrades to the M62 motorway.[66] There would also be a new "lifetime" Individual savings account (ISA) for the under-40s, with the government putting in £1 for every £4 saved. Those saving £4000 towards a house deposit were promised an annual £1000 top-up until they reached 50.[66] £100m was also allocated to tackle rough sleeping.[67] However, many charities complained that they thought Osborne's 2016 budget favoured big business rather than disabled people.[68] Following the UK's vote to leave the European Union in June 2016, Osborne pledged to further lower corporation tax to "encourage businesses to continue investing in the UK". Osborne had already cut the corporation tax rate from 28% to 20%, with plans to lower it to 17% by 2020.[70][71] See alsoReferences

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia