|

Cecil de Blaquiere Howard

Cecil de Blaquiere Howard, sometimes Cecil Howard, (April 2, 1888 – September 5, 1956), born in Clifton, Welland County, Ontario, Canada (today Niagara Falls) was an American painter and sculptor.[1][2] The sculptor devoted his work to the presentation of the human body in various circumstances and styles, in sports[3] or at rest, experimenting with figurative, polychrome sculptures, cubism, traditional African art, art deco, classicism or neoclassicism. Using different techniques, including modeling and direct carving, he worked with a range of materials, including clay, stone, marble, wood, plasticine, terracotta, plaster, wax, bronze and silver. BiographyHoward was the fourth child of British businessman George Henry Howard (1840–1896) and his wife Alice Augusta (née Farmer, 1850–1932). As the youngest son, Cecil was given his maternal grandmother's name "de Blaquiere" as his middle name. The family moved to Buffalo (New York) in 1890, and took American citizenship in 1896.[4] Howard left school early to study with James Earle Fraser at the Art Students' League of Buffalo,[5] which had recently relocated into the basement of the Albright–Knox Art Gallery, still under construction.[6] At the early age of sixteen,[7] he traveled to Paris to study at the Académie Julian with Raoul Verlet.[8] Soon he befriended Rembrandt Bugatti, whom he accompanied in 1909 on a journey to Antwerp, where together they made drawings and sculptures of animals in the Zoological Garden. Howard presented these early pieces at the Salon d'Automne in 1910, but later destroyed many of these plasters, as he regarded them as inferior in comparison to Bugatti's works.[8] After his return from Holland, the sculptor moved to a studio on the Avenue du Maine, in Montparnasse,[9] and regularly presented his works in Parisian salons and galleries. In 1913, Howard presented one of his earlier female nudes, simply entitled Woman, at the Armory Show in New York and Boston.[10] This was his first exhibition in the United States. In the early days of World War I, Howard served in an Anglo-French hospital as a stretcher-bearer, and in 1915 he joined an English Red Cross unit heading for Serbia, ravaged by war and typhus.[11] At the end of his six months engagement, he was back in Paris, and went on to produce a series of polychrome cubist sculptures, mainly inspired by scenes in Parisian dance-halls. By October 1915, after ten years in France, Howard returned to the United States for the annual exhibition of American sculpture at the Gorham Galleries in New York.[12] Four months later, after a few sales, he was back in Paris.[13] In November 1916 he featured again in the annual exhibition at the Gorham Galleries, where he presented Decorative Figure, a sculpture of a tall African woman bearing a vase on her shoulder, and L'Après-midi d'un faune (Afternoon of a Faun), representing two dancers, inspired by Nijinsky's innovative ballet.[14] Both pieces were exhibited the following months at the National Academy in Manhattan and at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts of Philadelphia.[15] In 1917, Howard befriended the poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire and in June of that year he played the role of the People of Zanzibar, providing on-stage accordion music and sound-effects, in the première of Apollinaire's «surrealist drama» Les Mamelles de Tirésias.[16]

During the inter-war period, Cecil Howard shared his time between France, England and the United States, producing some of his most important and creative works. After World War I, he received a commission to create two war memorials in Normandy. Several of his pieces were acquired by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, while Henry Luce also commissioned works from him. Very well acquainted with most of the Parisian art world, Howard occasionally socialised with his French fellow sculptors Charles Despiau, Antoine Bourdelle, and particularly Aristide Maillol. In 1925 the Whitney Studio Galleries of New York presented the first American exhibition dedicated exclusively to Cecil Howard's works.[17] Taking part in several international traveling art shows, like the Tri-National Art Exhibit, he also participated in the Century of Progress fair in Chicago in 1933, and was awarded two Grand Prix in the Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in 1937. His work was also part of the sculpture event in the art competition at the 1936 Summer Olympics.[18] After the declaration of World War II, when German troops invaded France, Howard drove an American Red Cross truck carrying food and medicine to the hastily erected prison camps around Paris. Five months later, his situation as an American became increasingly strained with the occupying authorities and he decided to head back to the United States with his family.

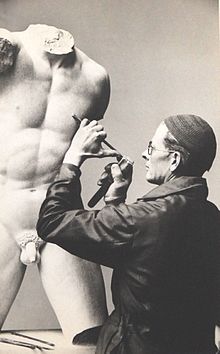

In late 1943, Cecil Howard exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, a male nude entitled American Youth or The Sacrifice, rewarded in 1944 by the George D. Widemer Memorial Gold Medal from the Academy.[19] The same year he became the sixteenth president of the National Sculpture Society, and was recruited by the Office of Strategic Services. From 1945 onward he worked for the United States Office of War Information, and three weeks after D-Day, he came ashore at Utah Beach, in Normandy. In 1947 Howard became Vice President of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and participated in an exhibition co-organised by the Whitney Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The same year, the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris bought a large sculpture of a reclining nude entitled Sun Bath, and in 1948 the French government awarded him the Legion of Honour. In 1953, for the 20th annual exhibition of the National Sculpture Society, he received the Herbert Adams Memorial Award Medal, and in 1954 the Architectural League of New York unanimously awarded him the highly coveted Golden Medal of sculpture. That same year, Cecil Howard featured in a long photo shoot by Andreas Feininger for Life magazine, and he also appeared in Uncommon Clay, Thomas Craven's documentary about six of America's leading sculptors at work in their studios. Cecil Howard died in New York in 1956 and was posthumously awarded the E. N. Watrous Gold Medal from the National Academy Museum and School in 1957.[20]

Collections

Bibliography and filmographyBooks in English

Books in French

References

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia