|

Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana

The Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana is the Jewish cultural and historical collection of the University of Amsterdam Special Collections. The foundation of the collection is the personal library of Leeser Rosenthal, whose heirs presented the collection as a gift to the city of Amsterdam in 1880. In 1877 the city library had become the University Library, so the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana was essentially given to the University. The Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana has since expanded to become the largest collection of its kind in Continental Europe, featuring manuscripts, early printed books, broadsides, ephemera, archives, prints, drawings, newspapers, magazines, journals, and reference books.[1] Historical backgroundLeeser Rosenthal (1794-1868)Leeser (Elieser) Rosenthal was born in Nasielsk, Poland on 13 April 1794 (13 Nisan 5554) to a family of rabbis and teachers. He moved to Germany at a young age, working as a teacher[2] in Berlin and Paderborn before settling in Hanover as a financially independent Klausrabbiner at the Michael David'sche Stiftung. It was in Hanover that Rosenthal met and married Sophie (Zippora) Blumenthal, with whom he had three children, George, Nanny, and Mathilde.[3] Rosenthal was fascinated by books on Jewish subjects, and developed an enthusiasm for collecting them. So much so that he spent his wife's dowry on purchasing more works to add to his growing collection.[4] By the time of his death in 1868, Rosenthal's collection was considered the largest private library in this field in Germany, consisting of more than 5,200 volumes that included 32 manuscripts, 12 Hebrew incunabula, and a selection of rare Hebraica and Judaica on the subjects of religion, literature, and history.[5] Amsterdam Leeser Rosenthal's son George (1828-1909) was a banker in Amsterdam when he inherited his father's library. George Rosenthal housed the library in his home on Amsterdam's Herengracht and commissioned the Dutch-Jewish bibliographer Meijer Roest (1821-1889) to compile a catalogue of the collection. The catalogue, entitled Catalog der Hebraica und Judaica aus der L.Rosenthal'schen Bibliothek was published in two volumes in 1875 with Leeser Rosenthal's own catalogue, Yodea Sefer as an appendix. Leeser Rosenthal's children wanted the library to remain undivided and serve as a public resource in memory of their learned father. To this end, they offered the collection to Chancellor Bismarck to be housed in the Kaiserliche und Königliche Bibliothek in Berlin, but he declined the offer. Offers to other European and American libraries also came to nothing. In 1880, the library of the city and university of Amsterdam moved to the former archery ranges on Singel canal, where there was space for the library to expand. Following this, Rosenthal's heirs decided to present their father's library to the city of Amsterdam. It was accepted 'with warmest thanks for a princely gift' and Meijer Roest was appointed curator the year after. Since the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana became part of the University of Amsterdam's library, the collection has been continually expanded in keeping with its assumed role as a modern, functional library covering all fields of Jewish study. Roest was succeeded as curator by Jeremias M. Hillesum (1863-1943), who made significant additions to the library. He, in turn, was followed by Louis Hirschel (1895-1944), who in 1940 completed a subject catalogue for the library.[6] World War IIThe occupation of the Netherlands led to the dismissal of curator Hirschel and his assistant M.S. Hillesum (1894-1943) in November 1940, and the closing of the reading room in the summer of 1941. The reading room was closed and a number of seals had been attached, but most of the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana was kept in the book storage depot. Some of the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana's manuscripts and incunables had already been placed in crates below the book depot since they were part of a single organisational unit along with those of the University Library. Herman de la Fontaine Verwey, the University librarian during the war, made plans with Hirschel to smuggle the most valuable books out of the reading room, using old seals discarded when new ones were applied. To their advantage, the only complete catalogue was a handwritten card index in Hebrew that they shuffled thoroughly in order to render it useless. Furthermore, the reading room was overstocked and had no shelf numbers, so they were able to remove a number of books without leaving noticeable gaps. These books were then placed with the University's other valuable books in a shelter in Castricum. Nevertheless, in June 1944 the order came for the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana to be removed. Through a fortunate combination of the enterprising nature of de la Fontaine Verwey, the cooperation of library staff, and the ignorance of those sent to pack up the library, the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana's journals, brochures, pictures and prints were saved.[7] The collection was earmarked for the Institute for Study of the Jewish Question and was transported to Germany. Thankfully nothing had yet been done with the books by the time the war ended, and most of the boxes of books were recovered in storage in Hungen, near Frankfurt am Main, and sent back to Amsterdam. The same could not be said for the curator, his assistant, and their families, who had also been deported.[8] Material available online

Highlights of the collections

The Pekidim and Amarkalim (officers and treasurers) formed an international organization whose purpose was to coordinate the fundraising to support impoverished Jews in Palestine. The organization maintained close contacts with the leaders of the Jewish communities in the cities of Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed and Tiberias. The archive, which contains 10,100 incoming letters, is a very important source for the early history of the Jewish settlement in Palestine in modern times.[9]

Jacob Israël de Haan was not one to keep things. He was prolific in his correspondence, but destroyed almost every letter he received and requested the recipients of his letters do likewise. He also did away with all manuscripts and preparatory stages of his books once they were published. That his archive, comprising four boxes of handwritten material and three with copies and clippings, exists is partially due to the fact that he was murdered, after which his house was sealed and his papers returned to his widow. De Haan also presented the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana with material during his lifetime, and more has been added to the archive since it was acquired.[10] The archive contains varied material dating from 1904-1984 (mostly 1904-1924), including correspondence, publications, lectures, poems, and photos. The archive contains few letters from De Haan's wife and family, mostly written after 1919. Meanwhile, all surviving business letters are from after 1923. The notes of the law lectures De Haan gave at the University of Amsterdam and the Law School in Jerusalem remain, as well as notebooks with drafts of hundreds of poems, published and unpublished.[11]

Arguably the most well known manuscript of the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana is the Esslingen Machzor. Completed by the scribe Kalonymos ben Judah on 12 January 1290 in Esslingen, it is a machzor for Yom Kippur and Sukkot. The manuscript is of a type of prayer book created in Ashkenaz in the mid-1200s and produced for about a century. These codices are all very large, suggesting they were made for community use. This is confirmed by the inscriptions in some volumes, their luxurious execution, and their profuse decoration.[12]

The Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana holds a late thirteenth century copy of Rabbi Isaac ben Moses of Vienna's famous work, Sefer Or Zarua. It was his magnum opus, and he is therefore often referred to as Isaac Or Zarua. Despite its nature as a halakhic work, Sefer Or Zarua provides plenty of historical information in the form of everyday traditions and local customs across Europe that makes it an interesting source for both religious and medieval historians.[13] This manuscript is one of only two extant medieval copies, the other being held at the British Library in London, and the basis for the first published edition of the work, published in 1862 in Zhytomyr. The Sefer Or Zarua preserves one of the earliest versions of the story of Rabbi Amnon of Mainz.[14]

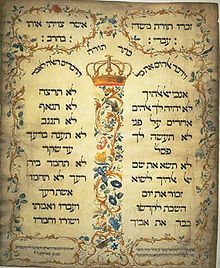

The Sefer Mitzwot Katan, SeMaK, or Small Book of Precepts, was composed by Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil in 1280, and is an abridged copy of the Great Book of Precepts by Moses ben Jacob of Coucy. The manuscript in the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana was copied by Hannah, daughter of Menachem Zion. It was extremely rare for women to write Hebrew medieval manuscripts. Indeed, fewer than ten female scribes are known compared with over four thousand known male scribes. However these figures can be misleading as the majority of manuscripts remain anonymous. Many girls were taught to read, but only those in families of scholars or scribes were taught to write, so there can nevertheless only be few more female scribes of medieval manuscripts.

The Hamburg-Altona school of Hebrew illuminated manuscripts was part of the revival of Hebrew manuscript illumination in the eighteenth century, and one of its most influential scribes was Joseph, son of David of Leipnik. Only thirteen manuscripts, all Haggadot written by Jodeph of Leipnik have been found, of which the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana Leipnik Haggadah is one. This Haggadah appears to have been intended as a personal gift, and includes an abridged version of Abravanel's commentary on the Haggadah, and a short mystical commentary. The Leipnik Haggadah was based on the two editions of the Amsterdam Haggadah (1695 and 1712), as was standard for eighteenth-century Haggadah manuscripts.[16] References

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia