|

Avalon Peninsula campaign

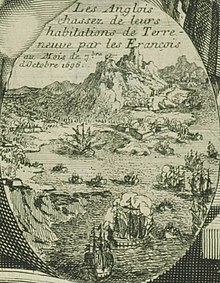

The Avalon Peninsula campaign occurred during King William's War when forces of New France, led by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville and Governor Jacques-François de Monbeton de Brouillan, destroyed 23 English settlements along the coast of the Avalon Peninsula, Newfoundland in the span of three months. The campaign began with raiding Ferryland on November 10, 1696, and continued along the coast until they raided the village of Heart's Content. After the Siege of Pemaquid, d'Iberville along with Father Jean Baudoin[1] led a force of Canadians, Acadians, Mi'kmaq, and Abenakis in the Avalon Peninsula campaign. They destroyed almost every English settlement in Newfoundland, over 100 English were killed, many times that number captured, and almost 500 deported to England or France.[2] Historical contextDuring this time period, the only French settlement on Newfoundland was Plaisance. Prior to the arrival of d'Iberville, Newfoundland's French Governor de Brouillon ordered a French naval squadron under Chevalier Nesmond to lay siege to St. John's in retaliation for earlier English attacks. In 1694, Nesmond set sail from Plaisance to lay siege to St. John's. This siege was unsuccessful. Two years later, however, the French made a second attempt. On September 12, 1696, Quebec's Governor Frontenac sent Pierre Le Moyne Sieur d'Iberville to Newfoundland. The previous August, d'Iberville had just been victorious in the Siege of Pemaquid, on the coast of present-day Maine. The campaignThe Newfoundland campaign involved a novel strategy: both a land and sea assault of the villages. D'Iberville attacked by land while Sieur de Brouillan attacked by sea. D'Iberville's strategy of attacking the settlement by land was the first recorded in Newfoundland and, as a result, the port villages were only prepared for an assault by sea. D'Iberville left Placentia on All Saints' Day (November 1) with his detachment of 124 men; soldiers, Acadians, and Indians. It was an 80 kilometres (50 mi), nine-day march across the Avalon Peninsula. Siege of FerrylandOn November 9, Sieur de Brouillan began the Siege of Ferryland. D'Iberville arrived on November 10, and the troops sacked Ferryland. Meanwhile, the 110 people of Ferryland fled to Bay Bulls and set about fortifying it. Raid on Cape BroyleD'Iberville set out against Bay Bulls using the small boats he had taken in Ferryland. On his way Cape Broyle was captured on November 12. Raid on Bay BullsHe then captured Bay Bulls on November 24, including a 100-ton merchant ship. Raid on Petty HarbourOn November 24, after a three-hour march from Bay Bulls, d'Iberville met up with his group of 20 scouts who had been sent to study the approaches to St. John's. Two days later, he encountered a detachment of 30 English soldiers posted on a hilltop near Petty Harbour. On November 26, d'Iberville charged and the enemy surrendered immediately. D'Iberville and his men were in command of the small port just eight kilometres south of St. John's. However, some colonists from Petty Harbour escaped to St. John's, where they alerted its residents. Siege of St. John'sAs d'Iberville marched into St. John's from Petty Harbour, English residents marched out the Waterford Valley to meet and repel the French. A pitched battle occurred in the Waterford Valley (Burnt Wood) and on the Heights of Kilbride (November 28). Of the 88 English defenders, 34 died in the battle. The English broke ranks and hastily retreated to St. John's. As d'Iberville approached St. John's, the English settlers scattered. Many sailed away, others escaped to the forests. A number of settlers and soldiers took refuge in Fort William. For three days the French laid siege to Fort William. On November 30, the English commander, Governor Miners, surrendered on condition that the English be allowed to leave St. John's. 230 men, women and children were sent off in a ship and duly arrived in Dartmouth, England. However a further 80 refugees were drowned when their ship foundered off the coast of Spain. After destroying St. John's, the French marched on Torbay (December 2), and Portugal Cove (December 5 and January 13). Internal struggles between de Brouillan and d'Iberville over the spoils of war followed. On December 25 de Brouillan left for Plaisance. The French burnt 80 shallops in the harbour (January 2). Raid on Conception BayThe villages on Conception Bay were the next targets. Holyrood (January 19) was first followed by Harbour Main (January 20) and Port de Grave (January 23). Battle of CarbonearOn January 24, 1697, two hundred permanent residents of Carbonear withdrew to Carbonear Island and successfully fended off the French and Indian attack on January 31. D'Iberville had only 70 men, the rest were dispersed in local skirmishes, holding villages and prisoners. Leaving Carbonear d'Iberville then attacked Old Perlican (February 4), Bay de Verde (February 6), Hants Harbour (February 7), New Perlican and Hearts Content (February 9). In many cases the local fishermen had fled to Carbonear. There was an unsuccessful attempt at a prisoner exchange (February 18). Frustrated, d'Iberville then sacked Brigus (February 11) and Port de Grave (February 11). Carbonear Island continued to hold out but d'Iberville torched their evacuated settlement on February 28 before leaving. D'Iberville then headed to Heart's Content before walking in a small group across the Avalon Peninsula isthmus. He arrived March 4 at Plaisance. D'Iberville then picked up his spoils of war, his scattered troops and approximately 200 prisoners at Bay Boulle (March 18-May 18). French attacks by sea on the remnants of the settlements continued into the spring (March 27-April 19). AftermathD'Iberville never returned to Newfoundland. These raids devastated the English settlements of Newfoundland. Every English settlement in Newfoundland had been destroyed and the English colony had been depopulated, except for Bonavista, which D'Iberville did not reach and the island holdout at Carbonear.[3] Estimates of eighty percent of the families were killed, deserted the village, were taken prisoner or were deported.[4] However, the English were able to recapture their Newfoundland territory in summer of 1697 with a strong relief force of 1500 troops. They found St. John's and all the English harbours on the Avalon abandoned, pillaged and every building destroyed. The English slowly began to rebuild and resettle. As a result of the campaign, the English government created permanent defences for Newfoundland. Previously the English had not built permanent fortifications or garrisons in Newfoundland as it was regarded as a seasonal fishing base. However, d'Iberville's devastating campaign had demonstrated the threat to the poorly defended colony. The following year, construction began on professionally engineered fortifications at Fort William.[5] D'Iberville continued his battles with the English, with the Battle of Hudson's Bay. See alsoReferences

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia