|

Art Nouveau posters and graphic arts

Art Nouveau posters and graphic arts flourished and became an important vehicle of the style, thanks to the new technologies of color lithography and color printing, which allowed the creation of and distribution of the style to a vast audience in Europe, the United States and beyond. Art was no longer confined to art galleries, but could be seen on walls and illustrated magazines. The Art Nouveau posters and illustrations almost always feature women, representing glamor, beauty and modernity. Images of men are extremely rare. Posters and illustrations are highly stylized. approaching two dimensions, and frequently are filled with flowers and other vegetal decoration. The major artists who created work in this domain included Aubrey Beardsley in Britain, The Czech Alphonse Mucha and Eugène Grasset, Jules Chéret, Georges de Feure and the painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec in France, Koloman Moser in Vienna, and Will H. Bradley in the United States. Art Nouveau poster designers, especially in the earlier years, had to work with the early technology of lithography, which in early versions limited the number of colors they could use. They are also very much influenced by Japanese prints, especially those of Hiroshige, with their flat planes and two dimensions, which were being popularized expositions in Paris during this period. BritainThe first appearance of the curving, sinuous forms that came to be called Art Nouveau is traditionally attributed to Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (1851–1942) in 1883.[1] They were soon adapted by pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones and Aubrey Beardsley in the 1890s. They were following the advice of the art historian and critic John Ruskin, who urged artists to "go to nature" for their inspiration.[2] In Britain, one of the first leading graphic artists in what became Art Nouveau style was Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898). He began with engraved book illustrations for Le Morte d'Arthur, then black and white illustrations for Salome by Oscar Wilde (1893), which brought him fame. In the same year, he began engraving illustrations and posters for the art magazine The Studio, which helped publicize European artists such as Fernand Khnopff in Britain. The curving lines and intricate floral patterns attracted as much attention as the text.[3]

FranceThe artist-designer Jules Chéret (1835–1932) was a notable early creator of French Art Nouveau posters. He helped turn the advertising poster into an art form. The son a family of artisans, he apprenticed with a lithographer and also studied at the École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs. Finding little work in Paris, he went to London, and designed furniture for a time, but then returned to Paris and had a great success in 1858 with a poster for Orpheus in the Underworld by Jacques Offenbach. He still struggled, and returned to London to design brochures. His breakthrough came in 1866 when a French perfume and toiletries maker, Eugene Rimmel, commissioned him to make advertising posters for his products. Rimmel funded Chéret to open the first color lithography shop in Paris. He experimented with different techniques and materials, first working in two colors, then 1869 advancing to three colors, black, red and combination color. He produced a wide variety of very popular posters, depicting idealized contemporary women, in posters for cosmetics and then for theater performances and ice skating rinks, including a famous poster for the Palais de Glace ice-skating rink in Paris (1896).

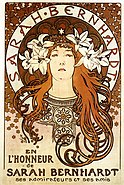

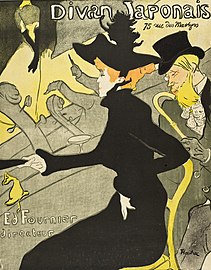

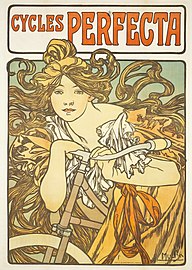

The Swiss-French artist Eugène Grasset (1845–1917) was another early creator of French Art Nouveau posters. He moved to Paris in 1871 and began designing ceramics, jewelry, furniture and tapestries. He gradually moved toward the graphic arts, and did an exceptional series of book illustrations and advertising posters. He helped decorate the famous cabaret Le Chat noir in 1885 and made his first posters for the Fêtes de Paris. He made a celebrated poster of Sarah Bernhardt in 1890, and a wide variety of book illustrations. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) was also a major figure in the early style. He began working together with two of the Les Nabis painters, Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, who turned him toward illustration. His Art Nouveau career was brief; he died at the age of 36 in 1901. Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939), born in Moravia in what is now the Czech Republic, trained as a painter in Munich for two years and then moved to Paris in 1887, where he struggled to survive. His moment came in December 1894, when he was asked, on very short notice, to create a poster for a new play, Gismonda, starring Sarah Bernhardt. His poster, a full-length portrait of Bernardt in costume against a background of Byzantine mosaic and sinuous lettering, became an immediate classic of Art Nouveau. Bernhardt signed him to a five-year contract, and, with each successive play and poster, his fame increased. Bernardt herself set aside a number of each new poster to sell them to collectors. Mucha was asked to produce posters for a variety of clients, from travel resorts to winemakers. The female figure were always highly stylized, and embellished with floral decoration and curling whiplash lines or The backgrounds were two-dimensional, filled with ornament but no depth. Mucha himself rejected the term Art Nouveau for his work, saying that "art cannot be new". He moved to Prague in 1910 to pursue more serious historical painting, a cycle of large-scale works called The Slav Epic.[4]

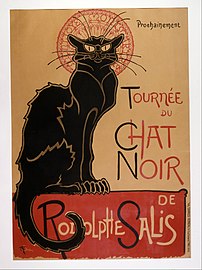

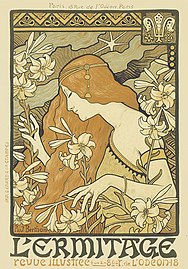

Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (1859–1923) was another important early Art Nouveau figure, whose work focused more on ordinary people and life in Montmartre, and political causes; besides making posters for cabarets, he illustrated socialist and anarchist publications. He made a famous poster for a cabaret called Le Chat Noir in 1896, with typical Art Nouveau curved lines and asymmetric print. Curling cat tails featured in several of his works.[5] Based on the success of his theater posters, Mucha made posters for a variety of products, ranging from cigarettes and soap to beer biscuits, all featuring an idealized female figure with an hourglass figure. He went on to design products, from jewellery to biscuit boxes, in his distinctive style.[6] Paul Berthon (1872–1909) was a notable figure of the later French Art Nouveau. A student of Eugène Grasset, he helped develop chromolithography, a more refined version of lithography which gave more accurate colors as well as the possibility of highlighting some colors over others. He specialized in portraits of women, either portraying them as idealized figures, taken from the style of the Pre-Raphaelites, as in the illustration for the cover of L'Hermitage, or as seducers, as in his poster for the Folies Bergere, depicting the dancer and courtesan Liane de Pougy luring men into a spider's web.[7]

Manuel Orazi (1860–1934) was born in Rome, but came to work in Paris in 1892 as an illustrator for novels and magazines. In 1895 he made a series of symbolist illustrations, called The Magic Calendar. His best known Art Nouveau work is the poster for La Maison Moderne, a shop of Art Nouveau interior design which competed with that of Samuel Bing, which combined a dozen aspects of Art Nouveau into a single illustration. Orazi also made illustrations of Sarah Bernhardt, including a poster of her as the Byzantine Empress Theodora, surrounded by mosaic patterns.[8] BelgiumThe first Art Nouveau architecture had appeared in Belgium in 1893, and Belgian graphic artists were quick to use the style. The most prominent was Henri Privat-Livemont, a member of the symbolist movement, who made his reputation as a member of the Circle of Artists of Schaerbeek, a group of artists in that neighborhood of Brussels. He became highly successful for the discreetly erotic women in his advertising posters, filled with the sinuous lines that were trademark of Art Nouveau.

Henri Meunier (1873-1922) was another very successful Belgian graphic designer and painter (1873–1922). The curling Art Nouveau lines appeared in each poster, in costumes or in the rising steam from a cup of coffee. His posters were so popular that he sold them to collectors by subscription, a practice soon followed by other prominent Art Nouveau poster designers, including Alphonse Mucha.

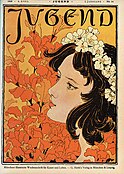

Munich Secession and JugendstilThe Munich Secession was an artistic movement which broke away from the more conservative fine arts establishment in Munich in 1892. Its creation inspired the better-known Vienna Secession a few years later.[9] The Jugendstil, or "Young Style", was centered in Munich, and was the German variant of Art Nouveau. Its most prominent graphic artist was Otto Eckmann, who produced numerous illustrations for the movement's journal, Jugend, in a sinuous, floral style that was similar to the French style. He also created a type style based upon Japanese calligraphy. Joseph Sattler was another graphic artist who contributed to the style through another artistic journal, called Pan. Sattler invented a type face often used in the Jugendstil. Another important German graphic artist was Josef Rudolf Witzel (1867–1925), who produced many early covers for Jugend with curving, floral forms which helped shape the style.

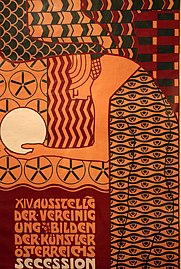

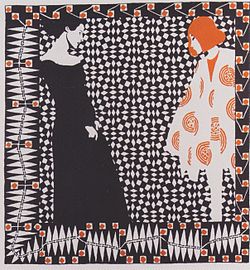

Vienna SecessionThe Vienna Secession was movement with a very different aesthetic and style from the Belgian and French Art Nouveau. The sinuous lines and floral designs of the early style were largely replaced by geometric patterns and symmetry. The painter Gustav Klimt made a venture into graphic arts, designing the poster for the Secession Exhibition of 1898. The major graphic artists of the Secession included Joseph Maria Olbrich, who designed posters for the exhibitions of the Secession, and also designed the gilded cupola for the Secession's gallery in central Vienna.

The Secession journal Ver Sacrum was a showcase the graphics of Koloman Moser and other Vienna designers.

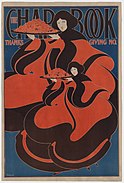

United StatesThe color lithograph advertising poster was introduced in the United States in 1893 by Harper's Magazine, which published a series of very popular posters. The rival of Scriber's was the Chapbook, which hired Will H. Bradley to design a poster in 1894 to celebrate Thanksgiving. This poster, called The Twins, with its two-dimensional format, similar to Japanese prints, and bold sinuous lines, is considered the first American Art Nouveau poster.[10] The Art Nouveau posters in the U.S., as in Europe, featured almost exclusively women. The range of colors was muted, partly because of the limitations of early color lithography, and partly by the choice of the artist. A popular theme of the era was the peacock design. The peacock was an early Christian symbol of immortality; it was used by James McNeill Whistler to decorate a room in London, by Louis Comfort Tiffany for a celebrated stained glass window, and by Bradley for The Modern Poster, advertising a book of that name by Scribner's publishers.[10] Art Nouveau style was especially popular for advertising bicycles, which were just becoming common. These posters were also aimed primarily at women, illustrating the freedom that a bicycle could bring.[11]

Louis John Rhead (1887–1926 was another important artist of Art Nouveau. Born in England, he studied in Paris, and moved to the United States in 1883, and became artistic director of the publishing house D. Appleton. His posters show the influence of the Pre-Raphaelite movement in England, He won a gold medal at the first international poster exposition held in Boston in 1895. He also illustrated children's books. Edward Penfield (1866–1923) was an illustrator and then the art editor of Harper's Magazine. His work was best known for its simplicity of line, with no excess ornament, so posters could be viewed easily at a distance.

Notes and citations

Bibliography

|

||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia