|

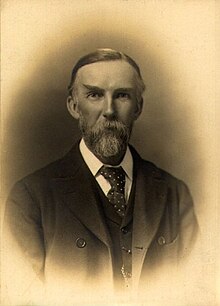

Alexander Kennedy

Sir Alexander Blackie William Kennedy FRS,[1] FRGS (17 March 1847 – 1 November 1928), better known simply as Alexander Kennedy, was a leading British civil and electrical engineer and academic. A member of many institutions and the recipient of three honorary doctorates, Kennedy was also an avid mountaineer and a keen amateur photographer being one of the first to document the archaeological site of Petra in Jordan following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Early life and worksKennedy was born in Stepney, London to Rev. John Kennedy, MA, and Helen Stodart Blackie, both from Aberdeen. His maternal uncle was John Stuart Blackie, a Scottish scholar. He received his early education at the City of London School, before taking a short course at the Royal School of Mines, Jermyn Street to give him a basic grounding in engineering. In 1864, he was apprenticed into the shipbuilding firm of J & W Dudgeon of Cubitt Town. He spent the next four years there working as a draughtsman and had a hand in the construction of the first ships with compound engines and twin screws.[2] By the time he left in 1868 he was one of a few draughtsmen in the country with a thorough understanding of the workings of both systems. He put this understanding to good use when he joined Palmers' Engine Works of Jarrow on Tyne upon completion of his apprenticeship, he became the leading draughtsman and designed the first compound engine to be built in the north. Having spent three years with Palmers he worked for a short time for T.M. Tennant and Company of Leith as their chief draughtsman.[3] PartnershipIn 1871 at the young age of 24 he was invited to become a partner of H.O. Bennett in Edinburgh. Over the next three years Kennedy was heavily involved with boiler design, building and testing. In 1873 he visited the Vienna Exhibition to study the boiler and engine designs exhibited there. He wrote a series of articles on several designs for the journal Engineering which were later reprinted in the official report on the exhibition made by the British Royal Commission.[3] Academic works In 1874, aged only 27, he was appointed to the chair of Engineering at University College, London, a post he would hold for the next 15 years (succeeded by Thomas Hudson Beare). He set about a series of changes that were to reform the way engineering was taught worldwide. He insisted that all of his students received not only lectures in engineering principles but also a firm grounding in mathematics, physics, chemistry, geology and the other sciences upon which engineering is based. He also asked that an engineering laboratory be built so that the students could have first hand experience of the applications of their theoretical studies.[4] This proposal met widespread support from the engineering profession and the presidents of the Institution of Civil Engineers and the Institution of Mechanical Engineers were among the leading figures who supported it. In 1878 the laboratory was built and put to use, it was the first of its kind in the world and proved so useful that over the next nine years ten other educational institutions followed Professor Kennedy's example and built their own.[5] Whilst working at the UCL he translated Franz Reuleaux's Theoretische Kinematik (1875, Vieweg und Sohn) into English for the first time in 1876 (with title The Kinematics of Machinery).[6] In August 1876 Kennedy gave two lectures at South Kensington on the kinematics of machinery.[7] In 1886, he published Mechanics of Machinery, the first time that a book based on Reuleaux's kinematic analysis had been published in English.[6] He also used the laboratory to carry out experiments to determine the strength and elasticity of various materials and was elected as a fellow of the Royal Society for this work in 1887. There followed a series of other experiments in which he investigated the strength of riveted joints and the possibility of developing new electric turbines.[8] ConsultancyKennedy found time outside of his academic works to establish an extensive consultancy business. His designs include the steel arched pier at Trouville-sur-Mer, the concrete structure and steelwork of the rebuilt Alhambra Theatre and the steelwork of the first Hotel Cecil.[8] He made great use of his laboratory to test his materials and his designs were always valued for the hours of research he had invested in them. During this period he was asked to investigate a remote oil concession in California which lay several days horse riding from the nearest road or railway. Kennedy had no riding experience and knew little about horses, however he immediately accepted the job and set about arranging riding classes in the mornings before he started lecturing. He soon became a very proficient rider and the trip to California proved a great success for Kennedy and the concession owners.[9] Electrical engineerIn 1889, Kennedy resigned his professorship and left the University turning to electrical engineering, which he had researched during his academic career. That year he established a very thriving private practise as a consulting engineer at Westminster in partnership with Bernard Maxwell Jenkin, (son of Fleeming Jenkin) with the firm adopting the name of Kennedy & Jenkin. His consultancy soon became famous for its works in this field. His first major contract was to design the supply system for the Westminster Electric Supply Corporation and he was retained by that corporation as their consultant engineer for the rest of his life.[9] He also worked for the Central Electric Company and the St James and Pall Mall Electric Light Company. Many towns first electric generating stations were built to his designs including those of Edinburgh, Glasgow, Manchester, Belfast, Croydon, Carlisle, Kirkcaldy, Weymouth, Hartlepool, York and Rotherham. Kennedy was contracted to build two hydroelectric stations for the British Aluminium Company, their first at the Falls of Foyers in 1896 and a second at Kinlochleven in 1909.[10] Kennedy also acted as a consultant to several railway companies in the London area, particularly in regard to electrification and tram systems. He advised the London County Council with regard to their tram network and instigated their use of unusual underground conduits for their electricity supply. In 1896 he was appointed engineer to the Waterloo and City Railway and the electrical systems were designed to his specifications. He held consultancy contracts with the London and Home Counties Electricity Authority, London Power Company, Edinburgh Corporation and the Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation.[11] Kennedy hired as his Assistant Engineer at the firm another climber, Sydney Donkin, who was made a partner in the business in 1908 and became senior partner in 1934 upon the retirement of the son of the founder. [citation needed] In 1932 the London Power Company commemorated Kennedy by naming a new 1,315 GRT coastal collier SS Alexander Kennedy.[12] Admiralty workIn 1900 Kennedy was asked by The Admiralty to serve as a member of the Belleville Boiler Committee to investigate the installation of French designed Belleville boilers on Diadem class cruisers.[11] This was the first in a long line of Admiralty commissions that he undertook which included work behind the front lines in France during the First World War. There followed several more admiralty appointments, serving on the Machine Design Committee from 1900 to 1906, the Ordnance Board in 1909 and on the government committee for wireless telegraphy in 1913. During the First World War his skills were in great demand and he served on many committees including the Panel of the Munitions Inventions Department; as chairman of the Committee on Gunsights and Rangefinders; Vice-Chairman of the Committee on Ordnance and Ammunition and as Vice-Chairman of the Anti-Aircraft Sub-Committee. After the war he was employed by the Ministry of Transport as chairman of the Electric Railway Advisory Committee.[13] Photography, the Alps & Petra Kennedy was a member of The Camera Club and served as their president in 1890.[14] As part of his duties on the Committee on Ordnance and Ammunition and the Anti-Aircraft Sub-Committee during World War I he was required to visit the Western Front where he took many photographs of the effects of the war and later published these in his account of the war, Ypres to Verdun, in 1921. He maintained a keen interest in mountaineering, in particular the Alps mountain range, and was a member of the Alpine Club. He used his inaugural presidential address to the Institution of Civil Engineers to highlight the impact the profession had upon the environment. Kennedy edited a revised edition of A.W. Moore's Alps in 1864: A Private Journal in 1902, illustrated with photographs he had taken of the area.[13] In 1922, aged 75, he visited the ruins of Petra in Jordan, then under British mandate, which had become much safer to visit after the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire following the First World War. The ruins fascinated him as an engineer and he returned the next year as the guest of Emir Abdullah. He returned for a third and final time in 1924 and was made a Pasha by the Emir. These excursions did, however, take their toll on his physical and mental health and Kennedy resigned himself to not to visit again. He published an account of the history of the area in his book Petra: its history and monuments published in 1925.[15][14] Personal lifeKennedy married Elizabeth Verralls Smith on 8 September 1874, in Cromdale, Inverallan and Advie, Inverness, Scotland. Together they had one daughter (Elizabeth Helen) and two sons (William Smith and Sir John MacFarlane). The younger son, John MacFarlane became a full partner of his father's firm, Kennedy & Jenkin, in 1908. He was widowed in 1911 and died at his home at 7a The Albany in London, on 1 November 1928. His great-grand daughter is Tessa Kennedy, mother of film producer Cassian Elwes, artist Damian Elwes, actor Cary Elwes, writer Dillon Kastner and film producer Milica Kastner. His great-grand-son is Christopher Kennedy, British photographer and sculptor, creator of the Photo Luminism photographic technique. UCL Kennedy Chair in Mechanical EngineeringUniversity College London named a Professorial Chair in Kennedy's honour. The Kennedy Chair was previously held by the university's Professor of Civil and Mechanical Engineering but is now the title of UCL's Professor of Mechanical Engineering. Kennedy Professors have included:

The Kennedy Chair of Mechanical Engineering is currently held by Professor Richard William Gordon BUCKNALL, who also serves as UCL Mechanical Engineering's Head of Department. Societies and institutions1878 – Member of Council of the Physical Society of London Honorary awardsDoctor of Laws, Glasgow University BibliographyThe Mechanics of Machinery MacMillan and Co., London (1886) References

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia