|

African crake

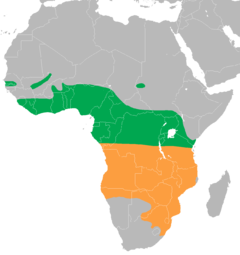

The African crake (Crecopsis egregia) is a small- to medium-size ground-living bird in the rail family, found in most of central to southern Africa. It is seasonally common in most of its range other than the rainforests and areas that have low annual rainfall. This crake is a partial migrant, moving away from the equator as soon as the rains provide sufficient grass cover to allow it to breed elsewhere. There have been a few records of vagrant birds reaching Atlantic islands. This species nests in a wide variety of grassland types, and agricultural land with tall crops may also be used. A smallish crake, the African crake has brown-streaked blackish upperparts, bluish-grey underparts and black-and-white barring on the flanks and belly. It has a stubby red bill, red eyes, and a white line from the bill to above the eye. It is smaller than the corn crake, which is also lighter-plumaged, and has an eye stripe. The African crake has a range of calls, the most characteristic being a series of rapid grating krrr notes. It is active during the day, and is territorial on both the breeding and non-breeding grounds; the male has a threat display, and may fight at territory boundaries. The nest is a shallow cup of grass leaves built in a depression under a grass tussock or small bush. The 3–11 eggs start hatching after about 14 days, and the black, downy precocial chicks fledge after four to five weeks. The African crake feeds on a wide range of invertebrates, along with some small frogs and fish, and plant material, especially grass seeds. It may itself be eaten by large birds of prey; snakes; or mammals, including humans, and can host parasites. Although it may be displaced temporarily by the burning of grassland, or permanently by agriculture, wetland drainage or urbanisation, its large range and population mean that it is not considered to be threatened. TaxonomyThe rails are a bird family comprising nearly 150 species. Although the origins of the group are lost in antiquity, the largest number of species and the most primitive forms are found in the Old World, suggesting that this family originated there. The taxonomy of the small crakes is complicated, but the closest relative of the African crake was for many years thought to be the corn crake (Crex crex) which breeds in Europe and Asia, but winters in Africa. The African crake was first described as Ortygometra egregia by Wilhelm Peters in 1854 from a specimen collected in Mozambique,[2] but the genus name failed to become established. For some time it was placed as the sole member of the genus Crecopsis[3] but subsequently moved to Crex, created for this species by German naturalist and ornithologist Johann Matthäus Bechstein in 1803.[4] Richard Bowdler Sharpe considered that the African bird differed sufficiently from the corn crake to have its own genus Crecopsis, and later authors sometimes placed it in Porzana, based on a resemblance to the ash-throated crake, P. albicollis. Structural differences rule out Porzana, and the placement in Crex became the most common and best-supported treatment,[5][6] until the International Ornithological Committee (IOC) 2020 world bird list moved the crake back to Crecopsis. This followed research that showed that the African crake was most closely related to the Rouget's rail, rather than the corn crake.[7][8] The genus name Crecopsis is derived from Crex and the Ancient Greek opsis "appearance",[9] and the species name egregia derives from Latin egregius, "outstanding, prominent".[10] Description The African crake is a smallish crake, 20–23 cm (7.9–9.1 in) long with a 40–42 cm (16–17 in) wingspan. The male has blackish upperparts streaked with olive-brown, apart from the nape and hindneck which are plain pale brown; there is a white streak from the base of the bill to above the eye. The sides of the head, foreneck, throat and breast are bluish-grey, the flight feathers are dark brown, and the flanks and sides of the belly are barred black and white. The eye is red, the bill is reddish, and the legs and feet are light brown or grey. The sexes are similar in appearance, although the female is slightly smaller and duller than the male, with a less contrasting head pattern. Immature birds have darker and duller upperparts than the adult, a dark bill, grey eye, and less barring on the underparts. There are no subspecific or other geographical variations in plumage. This crake has a complete moult after breeding, mainly prior to migration.[2] Although this species occurs in fairly open habitats, it lacks the pure white undertail used for signalling in open water or gregarious species like the coots and moorhens.[11] The African crake is smaller than the corn crake, which also has darker upperparts, a plain grey face and different underparts barring pattern. In flight, the African species has shorter, blunter wings with a less prominent white leading edge and deeper wingbeats than its relatives. Other sympatric crakes are smaller with white markings on the upperparts, different underparts patterns and a shorter bill. The African rail has dark brown upperparts, a long red bill and red legs and feet.[2] VoiceLike other rails, this species has a wide range of vocalisations. The male's territorial and advertising call is a series of rapid grating krrr notes repeated two or three times a second for several minutes. It is given most often in the breeding season, usually early or late in the day, but sometimes continues after dark or starts before dawn. The male stands upright with his neck extended when advertising, but will also call when chasing intruders on the ground or in flight. Both sexes give a sharp, loud kip call as an alarm or during territorial interactions, adapting a similar pose as for the advertising call. Once breeding starts, the birds become much quieter, but territorial birds commence the kip call again during the non-breeding season, especially when there is a high density of African crakes in the area. A wheezy kraaa is associated with threat displays and copulation; imitation of this call by a human can bring a rail to within 10 m (33 ft). Newly hatched chicks make a soft wheeeez call, and older chicks cheep.[2] The rasping advertising call is readily distinguished from the hwitt-hwitt-hwitt of spotted crake, the monotonous clockwork tak-tak-tak-tak-tak of striped crake, or the quick-quick of Baillon's crake.[12] The corn crake is silent in Africa.[13] Distribution and habitat The African crake occurs throughout sub-Saharan Africa from Senegal east to Kenya, and south to KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, except in arid areas of south and southwest Africa where the annual summer rainfall is less than 300 mm (12 in). It is widespread and locally common in most of its range, apart from the rainforests and the drier regions. Nearly all the South Africa population of about 8,000 birds occur in KwaZulu-Natal and the former Transvaal Province, and much good habitat is protected in the Kruger National Park and iSimangaliso Wetland Park. This crake is only a vagrant to southern Mauritania, southwest Niger, Lesotho, South Africa's northern and eastern Cape Province and North West Province,[2][14] and southern Botswana.[15] Further afield, it is rare on Bioko Island (Equatorial Guinea),[16] and there have been two records each for São Tomé and Tenerife, the Canary Islands birds being the first records for the Western Palearctic.[17][18] Holocene remains from North Africa suggest that the species was more widespread when the climate was wetter in what is now the Sahara.[19][20] This crake is a partial migrant, but although it is less skulking than many of its relatives, its movements are complex and poorly studied; the distribution map is therefore largely hypothetical. It is mainly a wet-season breeder, and many birds move away from the equator as soon as the rains provide sufficient grass cover to allow them to breed elsewhere. Southward movement is mainly from November to April, the return north beginning when burning or drought reduces the grass cover again. This species is present throughout the year in some West African countries, and in equatorial regions, but even in those areas numbers vary seasonally due to local movements; north-south migration has been noted within countries including Nigeria, Senegal, The Gambia, Ivory Coast and Cameroon.[2] Migration involves small groups of up to eight birds.[1] It may be one or two months after the rains begin before the grass is sufficiently high for breeding birds to arrive. Even in southern Africa, some birds may stay after breeding if enough usable habitat remains.[15] The habitat is predominantly grassland, ranging from wetland edges and seasonal marshes to savanna, lightly wooded dry grassland, and grassy forest clearings. The crake also frequents corn, rice and cotton fields, derelict farmland and sugarcane plantations close to water. A wide range of grass species are used, with a preferred height of 0.3–1 m (0.98–3.28 ft) tall but vegetation is acceptable up to 2 m (6.6 ft) tall. It normally prefers moister and shorter grassland habitats than does the corn crake, and its breeding territories often contain or are close to thickets or termite mounds. It occurs from sea level to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) but is rare in the higher altitude grasslands. Its grassland habitat is frequently burned in the dry season, forcing the birds to move elsewhere.[2] In an East African study, the average area occupied by one bird was 2.6 hectares (6.4 acres) when breeding, and 1.97 to 2.73 ha (4.9 to 6.7 acres) at other times.[21] The highest densities occur in lush or moist grassland such as the Okavango Delta.[15] Behaviour The African crake is active during the day, especially at dusk, during light rain, or after heavier rain. It is less skulking and easier to flush from cover than other crakes, and is often seen at the edges of roads and tracks. An observer in a vehicle can approach to within 1 m (3.3 ft). When a bird is flushed it normally flies less than 50 m (160 ft), but new arrivals may occasionally fly twice as far. A flushed crake will frequently land in a wet area or behind a thicket, and crouch on landing. In short grass, it can escape from a dog using its speed and manoeuvrability, running with the body held almost horizontal. It may roost in a depression near grass tussock and it will bathe in puddles.[2] The African crake is territorial on both the breeding and non-breeding grounds; the male threat display involves the bird standing upright and spreading the feathers of the flanks and belly like a fan to show the barred underparts. He may march towards the intruder, or walk side by side with another displaying male. The female may accompany the male, but with feathers less widely fanned. Fighting at territorial boundaries involves the male birds jumping at each other and pecking. Paired females will attack other females in the territory, especially if the male has shown an interest in them.[2] Breeding Breeding behavior commences with a courtship chase with the female running in a crouch, pursued by the male, who adopts a more upright stance and has his neck outstretched. The female may stop and lower her head and tail to allow copulation; this takes just a few seconds, but may be repeated several times in an hour. The nest is a shallow cup of grass leaves, sometimes with a loose canopy, built in a depression and hidden under a grass tussock or small bush; it may be on dry ground or slightly raised above standing water, or occasionally floating. The nest is about 20 cm (7.9 in) across with the internal cup 2–5 cm (0.79–1.97 in) deep, and 11–12 cm (4.3–4.7 in) wide. The clutch size is from 3 to 11 pink-coloured[22] eggs; the first is often laid when the nest is little more than a pad of grass, and a further egg is laid on each subsequent day. Both sexes incubate, and the eggs start hatching after about 14 days; all hatch with 48 hours despite the extended laying period. The black, downy precocial chicks soon leave the nest but are fed and protected by the parents. Fledging occurs after four to five weeks, and the young can fly before they are fully grown. It is not known whether a second brood is raised.[2] FeedingThe African crake feeds on invertebrates including earthworms, gastropods, molluscs and the adults and larvae of insects, especially termites, ants, beetles and grasshoppers. Vertebrate prey such as small frogs or fish may also be taken. Plant material is eaten, especially grass seeds, but also green shoots, leaves and other seeds. The crake searches for food both within vegetation and in the open, picking insects and seeds from the ground, turning over leaf litter, or digging with its bill in soft or very dry ground. It will chase faster moving prey, reach up to take food from plants, and wade to pluck food items from the water.[2] Crop plants such as rice, maize and peas may sometimes be eaten, but this bird is not an agricultural pest species.[23][24] It forages singly, in pairs or in family groups, sometimes in association with other grassland birds such as great snipes, blue quails and corn crakes.[2] Chicks are fed mainly on animal food. As with other rails, grit is swallowed to help break up food in the stomach.[25] Predators and parasitesPredators include the leopard,[26] serval, cats, the black-headed heron, dark chanting goshawk, African hawk-eagle and Wahlberg's eagle.[2] In South Africa, newly hatched chicks were taken by a boomslang.[27] If surprised, an African crake will leap vertically into the air before running away, a tactic believed to help it to evade snakes or terrestrial mammals.[28] Parasites of this species include ticks of the family Ixodidae,[29][30] and a feather mite, Metanalges elongatus, of the subspecies M. e. curtus. The nominate form of the mite occurs thousands of kilometres away in New Caledonia.[31] StatusThe African crake has a huge breeding range estimated at 11,700,000 km2 (4,500,000 mi2). Its population is unknown, but it is common in most of its range, and its numbers appear to be stable. It is therefore classed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.[1] Overgrazing, agriculture and the loss of wetland and moist grassland have reduced the availability of suitable habitat in many areas, such as some parts of the southern KwaZulu-Natal coast which have been urbanised or planted with sugarcane. In other areas, grassland may have increased locally in recent years as woodland is cleared. This crake is considered to be good eating, and is killed for food in some regions. Despite these adverse factors, it appears to be under no real threat.[2] Although most rails in the Old World are covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA), the African crake is not listed even in Kenya, where it is considered "near-threatened". Like its relative, the corn crake, it is too terrestrial to be classed as a wetland species.[32] References

Cited texts

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Crex egregia. Wikispecies has information related to Crex egregia.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia