インドガビアル (Gavialis gangeticus )は、インドガビアル科 インドガビアル属 に分類されるワニ の一種。インドガビアル属唯一の現生種。単にガビアル とも呼ばれる。ワニの中でも大型で、雌は全長2.6 - 4.5 m、雄は全長3 - 6 mに達する。成体の雄は吻端に特徴的な突起があり、現地で「ガラ」と呼ばれる壺に似ていることから「ガリアル」と呼ばれるようになった。細長い吻には110本の鋭い歯があり、魚を捕らえるのに適している。

インドガビアルはおそらくインド亜大陸 北部で進化した。シワリク丘陵 とナルマダー川 渓谷の鮮新世 の堆積物からインドガビアルの化石が発掘されている。現在はインド亜大陸北部の平野部の川に生息している。ワニの中では最も水生傾向が強く、陸上に出るのは日光浴と砂州での巣作りのときのみである。冬の終わりに交尾し、雌は春に集まって巣を掘り、20 - 95個の卵を産む。雌は巣と幼体を守り、幼体はモンスーン の到来前に孵化する。幼体は最初の1年間は浅瀬に留まって餌を探すが、成長するにつれて深場に移動する。

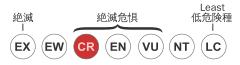

野生のガビアルの個体数は1930年代から大幅に減少し、現在の分布域は歴史的分布域のわずか2%にまで減少している。インドとネパールで開始された保護プログラムは、1980年代初頭から飼育下で繁殖されたガビアルの再導入を行っている。砂の採掘や農地への転換による生息地の喪失、餌である魚類の枯渇、有害な漁法により個体数が減少している。2007年以来、 IUCN のレッドリスト では近絶滅種 とされている。

人間文化において古くから扱われており、インダス川 流域でガビアルを描いた約4000年前の粘土板が発見された。ヒンドゥー教 では、インドガビアルは川の神ガンガー の乗り物とされる。川の近くに住む人々は、インドガビアルに神秘的な力と治癒力があると信じ、その体の一部を伝統医学 における薬の材料として使用していた。

「gharial(ガリアル)」という名前は、ヒンドゥスターニー語 で陶器の壺を意味する「ghara(ガラ)」に由来し、成体雄の鼻先にある突起に由来している。「gavial(ガビアル)」とも呼ばれる[ 5] [ 6] ベンガル語 の「mecho kumhir」の翻訳であり、魚を意味する「māch」とワニを意味する「kumhir」に由来する[ 7] [ 8] ガビアル という場合は本種を指し、ガンジスワニ とも呼ばれる[ 6]

1789年にヨハン・フリードリヒ・グメリン によって、Lacerta gangetica として記載された[ 9] Lacerta (現在はカナヘビ科 の属) は1758年にカール・フォン・リンネ が提案した属で、当時知られていた他のワニや様々なトカゲが含まれていた[ 10] クロコダイル属 に分類した。現在もクロコダイル科に含める説もある[ 11] [ 12] [ 13]

インドガビアル属 Gavialis は1811年にニコラウス・ミヒャエル・オッペル (英語版 ) [ 18] Rhamphostoma という属名は、1830年にヨハン・ゲオルク・ヴァーグラーが提案したもので、彼はこの属にCrocodilus gangeticus と Crocodilus tenuirostris の2種が含まれると考えていた[ 19]

インドガビアル科 Gavialidae は1854年に動物学者のアーサー・アダムズによって提唱され、インドガビアル属のみが分類されるとした[ 20] Gavialis gangetica は、1864年にアルベルト・ギュンター によって使用された学名であり、彼は L. gangetica 、C. longirostris 、C. tenuirostris をシノニムとし、インドガビアル属を単型分類群とした[ 21] ジョン・エドワード・グレイ は、ロンドン自然史博物館 にある標本を調査した。彼も1869年にインドガビアル属を単型とした。また、彼は細い顎と類似した歯列から、マレーガビアル もインドガビアル科に分類した[ 4]

1886年にリチャード・ライデッカー が提唱した Gharialis hysudricus は、シワリク丘陵で発見された頭蓋骨の化石に基づいており、当時知られていたガビアルの頭蓋骨の化石よりも大きかった[ 22] [ 23]

インドガビアルの進化と他のワニ類との関係および分岐については、議論の的となっている[ 24] [ 25] [ 26] 血漿タンパク質 の分岐度が低いことから、インドガビアルは他のワニ類よりもずっと遅く進化したと示唆した。インドガビアルはこの特徴をマレーガビアルと共有しているため、マレーガビアルと姉妹群 を形成することが示唆された[ 27] [ 28] [ 29] [ 30] [ 31] 分子遺伝学 と分子年代測定によると、約3800万年前の始新世 にインドガビアルとマレーガビアルの間に遺伝的分岐があったことが示されている[ 32]

インドガビアル属は、前期中新世 にインドとパキスタンで発生した[ 33] ハリヤナ州 とヒマーチャル・プラデーシュ州 のシワリク丘陵で発掘されたインドガビアルの化石は、鮮新世 から前期更新世 の間のものである[ 34] エーヤワディー川 渓谷の2か所でも発見されており、後期更新世のものである[ 35] Gavialis bengawanicus [ 33] G. bengawanicus の化石は、ガビアルが河川を通じて分散したという仮説を支持している[ 36] G. bengawanicus は唯一有効な絶滅したインドガビアル属の種である[ 37]

現存する主要なワニ類の系統図は、最新の分子研究に基づいており、インドガビアルとマレーガビアルの近縁関係、そしてガビアル科とクロコダイル科がアリゲーター科よりも近縁であることを示している[ 30] [ 38] [ 39] [ 32] [ 40]

以下は、絶滅した種も含め、ガビアル科内のインドガビアルの位置を示す詳細なクラドグラムである[ 32]

体色はオリーブ色で、成体は幼体よりも体色が濃く、幼体には暗褐色の横縞と斑点がある[ 41] [ 42] [ 43] [ 41] [ 12]

吻部は非常に細長く[ 13] [ 12] [ 11] [ 44] [ 12] [ 41] [ 5] 鼻骨 はかなり短く、前上顎骨 から大きく離れている[ 12] 頬骨 は隆起し[ 41] [ 45] [ 39]

雄は性成熟すると、鼻先に球根状の突起が発達する[ 43] [ 46] 性的二形 を持つ唯一の現生ワニである[ 45] [ 47]

雌は全長2.6 mで性成熟し、最大4.5 mまで成長する。雄は全長3 m以上で成熟し、最大で6 mまで成長する[ 48] [ 5] [ 49] [ 50] ファイザーバード のガーグラー川 で体長6.55 mのインドガビアルが死亡したと主張されているが、信頼できる計測は行われていない[ 51] [ 52]

水深が深く水が澄んで流れの速い河川 に生息する[ 13] [ 44] パキスタン のインダス川 、インド のガンジス川 、インド北東部とバングラデシュ のブラマプトラ川 からミャンマー のエーヤワディー川 に至るまで、インド亜大陸 北部の主要な河川水系で繁栄していた[ 45] パンジャーブ を流れるインダス川支流では一般的であると考えられていた[ 53] [ 54] [ 48] [ 5] ゴーダーヴァリ川 にも生息していたが、1940年代後半から1960年代にかけて乱獲され絶滅した[ 55] コシ川 では1970年以降絶滅したと考えられていた[ 56] ゴールデンマハシール を含む大型魚が生息していたアッサム州 のバラク川 に数多く生息していた[ 57] ミゾラム州 、マニプル州 を流れるバラク川の支流でも少数の個体が目撃されたが、調査は行われなかった[ 58] シュウェリ川 でガビアルが射殺された[ 59] [ 35]

1976年までに、その世界的な生息域は歴史的な生息域のわずか2%にまで減少し、生き残ったインドガビアルは200頭未満と推定された[ 45] ブータン 、ミャンマーでは局所的に絶滅している[ 5] [ 2]

ネパールでは、ガンジス川の支流であるバルディア国立公園 のカルナリ・ババイ川 水系[ 50] [ 60] チトワン国立公園 のナラヤニ ・ラプティ川水系に小規模な個体群が存在し、個体数はゆっくりと回復している[ 61] [ 62] [ 63]

インドでは、以下の地域にガビアルが生息している。

ジム・コーベット国立公園 のラムガンガ川 では、1974年に5頭のインドガビアルが記録された。飼育下繁殖個体は1970年代後半から放たれた。個体群は2008年から繁殖しており、2013年までに成体は約42頭に増加した[ 64] [ 65] [ 66] ガンジス川では、2009年から2012年の間にハスティナプール野生動物保護区 に494頭のインドガビアルが放された[ 67] [ 68]

ギルワ川では、1979年以来、飼育下個体によって小規模な繁殖個体群が維持されてきた[ 69] [ 2] [ 70] [ 71]

ガンダキ川ではトリヴェニダム下流、ヴァルミキ保護区の西、ソハジ・バーワ自然保護区に隣接した場所に生息する[ 72] [ 73]

チャンバル川 では、1974年に107頭のインドガビアルが記録された。1979年以降、飼育下繁殖個体が放たれ、1992年には1,095頭にまで増加した[ 74] [ 75] [ 76] [ 77] パールヴァティー川はチャンバル川の支流で、2015年頃からインドガビアルがいくつかの砂州に生息しており、2016年には29頭のインドガビアルが観察され、2017年には2つの営巣地で251頭の幼体が観察された[ 77]

ヤムナー川 では、2012年秋にケーン川との合流点付近で8頭の幼体が発見された。おそらくチャンバル川で繁殖している個体群の子孫であり、モンスーンの洪水で下流に流されてきたものと思われる[ 78] ソン川では1981年から2011年の間に164頭の飼育個体が放された[ 79]

ビハール州 のコシ川 では、2019年1月下旬、ガンジスカワイルカ を対象とした調査中に、約175kmの範囲で日光浴をしている2頭のインドガビアルが目撃された。これは1970年代以来、この川で野生のインドガビアルが記録された初めての事例である[ 80] オリッサ州 のマハナディ川 では、1977年から1990年代初頭にかけて約700頭のインドガビアルが放された[ 69] [ 81] [ 82] 1979年から1993年の間に、カジランガ国立公園 とディブルー・サイコーワ国立公園の間のブラマプトラ川 上流域で20頭未満の個体が目撃された。この個体群は、商業漁業、密猟、地元民による繁殖地への侵入、森林伐採後の川床の沈泥により減少した。1998年には、生存可能ではないと判断された[ 83] [ 84] バングラデシュでは、 2000年から2015年の間にパドマ川 、ジャムナ川、マハナンダ川 、ブラマプトラ川でインドガビアルの生息が確認された[ 85]

ワニの中では最も水生傾向が強い[ 48] 日光浴 をするときだけ水から出る[ 8] 変温動物 であるため、暑い時期には体を冷やし、周囲の温度が低いときには体を温める[ 86] [ 48] [ 87]

インドガビアルは生息域の一部でヌマワニと生息地を共有している。両者は同じ場所に巣を作るが、日光浴をする場所は異なる[ 88] [ 89] ヘビ 、カメ 、鳥 、哺乳類 、動物の死骸など、インドガビアルよりも多様な獲物を捕食する[ 90]

鋭く絡み合った歯と、水中でほとんど抵抗を受けない細長い吻を持っているため、水中で魚を狩るのに適応している。獲物を噛み砕かず、丸呑みする。若いインドガビアルは、魚を頭から飲み込み、自分の頭を後ろに引いて食道に押し込む様子が観察されている。若いインドガビアルは、昆虫 、オタマジャクシ 、小魚、カエル を食べる。成体は小型甲殻類 も食べる。インドガビアルの胃の中からは、ガンジススッポン の残骸も発見されている。インドガビアルは、大型の魚を引き裂き、石を胃石 として飲み込むが、これは消化を助けるか、浮力を調整するためである。インドガビアルの中には、宝石が入っているものもあった[ 48] [ 91]

食性は動物食で、主に魚類 を食べるが、鳥類 や哺乳類 などを食べることもある[ 13] [ 44]

雌は全長約2.6 mで成熟する[ 48] [ 92] [ 45] 性成熟 を示し、音を共鳴し、繁殖行動のために使用される[ 93]

求愛と交尾は晩冬の2月中旬までに始まる。乾季のチャンバル川で観察される繁殖期の雌は、定期的に80 - 120km移動し、繁殖する雌の群れに加わって一緒に巣を掘る[ 87] [ 48] [ 94] [ 45] [ 95] 温度依存性決定 である可能性が高い[ 48] [ 45] [ 87]

1980年代に観察された飼育下の雄は巣の保護には参加しなかった。飼育下の雄は孵化したばかりの幼体に興味を示し、雌は雄が背中に孵化したばかりの幼体を乗せることを許していた[ 96] [ 97]

ラクナウ 近郊の保護センターで生まれた若い個体孵化したばかりのガビアルは全長34 - 39.2 cm、体重82 - 130 gである。2年で80 - 116 cm、3年で130 - 158 cmに成長する[ 48] [ 98]

生後1年の若い個体は、倒木の残骸に囲まれた浅瀬に隠れて餌を探す[ 48] [ 99]

若い個体は、対角線上の両脚を同時に押し出すことで前進する。幼いうちは疾走(ギャロップ)することもできるが、緊急時のみに行う。8 - 9ヶ月齢で全長約75cm、体重約1.5kgに達すると、後脚と前脚を同時に押し出す成体の移動方法に変わる。成体は他のワニのように陸上で半直立姿勢で歩くことはできないため、陸上でうまく活動することができない[ 44] [ 8]

インドガビアルの個体数は、1946年の5,000 - 10,000頭から2006年には250頭未満にまで減少したと推定されており、3世代で96 - 98%減少している。インドガビアルは漁師に殺されたり、皮革、トロフィー、土着の薬用に狩猟され、卵は食用とされた。残った個体はいくつかの断片化された集団を形成している。狩猟は現在大きな脅威とは見なされていない。野生の成熟個体は、1997年の436頭から、2006年には250頭未満にまで減少した。この減少の理由の1つは、インドガビアルの生息地で漁業に刺し網 が多く使用されるようになったことである。もう1つの主な理由は、ダム 、堰堤 、灌漑 用の水路、人工堤防の建設、泥の沈殿や砂の採掘により河川環境が変化したことである。川沿いの土地は農業 や家畜 の放牧 に利用されている[ 2]

2007年12月から2008年3月の間にチャンバル川で111頭のインドガビアルの死骸が発見されたとき、当初は毒物か違法な漁網の使用により網に絡まって溺死したのではないかと疑われた[ 75] 鉛 やカドミウム などの重金属 が高濃度で検出された。これらの重金属と、胃潰瘍 や原生動物 の寄生虫 が死因と考えられた[ 100] [ 101] [ 60]

インドガビアルはワシントン条約 付属書Iに掲載されている[ 2] [ 45] [ 50]

チトワン国立公園 の繁殖施設で生まれた個体1970年代後半から、インドガビアルの保護活動は再導入に重点が置かれてきた。インドとネパールの保護区の川には、飼育下で繁殖した2 - 3歳の全長約1 mの個体が放流されていた[ 2]

1975年、インド政府の支援のもと、オリッサ州の保護区で保護プロジェクトが立ち上げられた。このプロジェクトは、国際連合開発計画 と国際連合食糧農業機関 の財政援助を受けて実施された。インド初の繁殖施設はナンダンカナン動物園 に建設された。繁殖プロジェクト立ち上げに伴い、フランクフルト動物園 から雄個体が空輸された。その後数年で、いくつかの保護区が設立された[ 102] ウッタル・プラデーシュ州 に繁殖センターが2つ設立された。1つは保護林に、もう1つは野生生物保護区に建てられ、毎年最大800個体を孵化育成し、川に放流している[ 103] [ 45] [ 104] [ 79] パンジャーブ州 のビアース川 にも若いインドガビアルが放流されている[ 2]

ネパールでは、1978年以来、採取された卵をチトワン国立公園内の保護繁殖センターで孵化させている。最初の一群である50個体のインドガビアルは1981年春にナラヤニ川に放たれた。その後、インドガビアルは国内の他の5つの川にも放たれた[ 50] [ 105] [ 106] [ 62] [ 105] [ 107]

飼育下個体の放流は、生存可能な個体群の回復には大きく貢献しなかった[ 2] [ 108] [ 109] [ 110]

2023年5月、パキスタンのパンジャーブ地方でインドガビアルの目撃情報が報告された。これは、30年ほど姿を消していたとみられる同種のパキスタンにおける初の目撃となった。これらの目撃情報を受けて、WWFは他のパートナーと協力してインドガビアルの保護活動を強化することを目指している。目標は、新たに発見された個体群を生存させ、反映させることである。パキスタンは、同種を再導入するため、ネパールから数百匹のインドガビアルの移送を要請している[ 111] [ 112] [ 113]

ギルワ川の川岸では、2019年に砂州と川中島の木本植物が除去され、2020年には砂が追加され、約1,000平方メートルの人工砂州が作られた。この介入により、この場所の土壌温度が安定し、最適化された。この川沿いのガビアルの巣の数は2018年の25から2020年には36に増加し、未孵化卵と幼体の死亡数は大幅に減少した[ 114]

フロリダの動物園の飼育個体 1999年時点では、インドではマドラス・クロコダイル・バンク・トラスト、マイソール動物園 、ジャイプール動物園 、ククライル・ガビアル・リハビリテーションセンターなどでガビアルが飼育されていた[ 115]

ヨーロッパでは、チェコ共和国 のプラハ動物園 とプロティヴィーン動物園、ドイツのベルリン動物園 でガビアルが飼育されている[ 116] [ 117]

アメリカ合衆国では、ブッシュガーデン・タンパベイ、クリーブランド・メトロパーク動物園、フォートワース動物園、ホノルル動物園 、サンディエゴ動物園 、スミソニアン国立動物園、サンアントニオ動物園、セントオーガスティン・アリゲーター・ファームでインドガビアルが飼育されている[ 45] ブロンクス動物園 とロサンゼルス動物園 は2017年にインドガビアルを導入した[ 118] [ 119] [ 120]

日本では野毛山動物園 とiZoo のみで飼育されている。ワシントン条約に加え、ガビアル科単位で特定動物 に指定されているため、個人での飼育は出来ない[ 121]

ガビアルが描かれた『バーブル・ナーマ 』の挿絵、インドの国立博物館 収蔵[ 122] インドガビアルの最も古い描写は、インダス文明 に遡る。印章や粘土板には、口に魚をくわえ、魚に囲まれたインドガビアルが描かれている。粘土板には、ガビアルと魚に囲まれた神が描かれている。これらの破片は約4,000年前のもので、モヘンジョダロ とシンド州 のアムリで発見された[ 123]

紀元前3世紀に遡るサーンチー の仏塔 の柱の岩の彫刻の一つにガビアルが描かれている[ 124] ガンガー と風と海の神ヴァルナ の乗り物である[ 125] バーブル は著書『バーブル・ナーマ 』の中で、 1526年にガジプル とバラナシ の間のガガラ川でインドガビアルが目撃されたと記している[ 126]

1915年、イギリス人将校がインダス川沿いで漁師がガビアルを狩る伝統的な方法を観察した。漁師は砂州近くの水面下約60 - 75cmの深さに網を張り、ガビアルが川から上がって日光浴をするのを隠れて待った。しばらくすると漁師は隠れ場所から出て、驚いたガビアルは川に飛び出して網に絡まった[ 127]

ネパールの人々は、雄のガビアルのコブに神秘的な力があると信じ、コブを得るためにガビアルを殺した[ 128] タルー の人々は、コブを野原で燃やすと虫や害虫を寄せ付けないと信じ、ガビアルの卵は咳止め薬や媚薬として効果的であると信じていた[ 50] 水葬 者を食べるとみなされており、消化管の内容物から装飾品が発見された例もあるが、実際に死骸を食べたのか胃石 として装飾品を食べたのかは不明である[ 11] [ 48]

ネパール語 では「Lamthore gohi」や「Chimpta gohi」 (gohiはワニの意味)、ヒンディー語 では「Gharial」、マラーティー語 で「Susar」 、ビハール語 で「Nakar」や「Bahsoolia nakar」 、オリヤー語 で「Thantia kumhira」(「Thantia」はサンスクリット語 でくちばし、鼻、象の鼻を意味する「tuṇḍa」に由来)などがある。オリヤー語ではオスは「Ghadiala」、メスは「Thantiana」と呼ばれている[ 7]

^ Rio, J. P. & Mannion, P. D. (2021). “Phylogenetic analysis of a new morphological dataset elucidates the evolutionary history of Crocodylia and resolves the long-standing gharial problem” . PeerJ 9 : e12094. doi :10.7717/peerj.12094 . PMC 8428266 . PMID 34567843 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8428266/ . ^ a b c d e f g h Lang, J.; Chowfin, S. & Ross, J. P. (2019). “Gavialis gangeticus ” . IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019 : e.T8966A149227430. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/8966/149227430 2 July 2024 閲覧。

^ “Appendices CITES ”. cites.org . 2024年7月2日 閲覧。 ^ a b Gray, J. E. (1869). “Synopsis of the species of recent Crocodilians or Emydosaurians, chiefly founded on the specimens in the British Museum and the Royal College of Surgeons” . The Transactions of the Zoological Society of London 6 (4): 125–169. doi :10.1111/j.1096-3642.1867.tb00575.x . https://archive.org/details/transactionsofzo06zool/page/132 .

^ a b c d e Stevenson, C. & Whitaker, R. (2010). “Gharial Gavialis gangeticus ” . In Manolis, S. C. & Stevenson, C.. Crocodiles. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan (Third ed.). Darwin: Crocodile Specialist Group. pp. 139–143. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/23_G-6764939a.pdf

^ a b 中井穂瑞嶺『ディスカバリー 生き物再発見 ワニ大図鑑』誠文堂新光社、2023年4月15日、218-224頁。ISBN 978-4-416-52371-1 。

^ a b Daniel, J. C.「Gharial, or Long-snouted Crocodile Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin)」『The Book of Indian Reptiles』Bombay Natural History Society and Oxford University Press、Bombay and Oxford、1983年、15–16頁。ISBN 9780195621686 。

^ a b c Bustard, H. R. & Singh, L. A. K. (1977). “Studies on the Indian gharial Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin) (Reptilia, Crocodilia) change in terrestrial locomotory pattern with age” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 74 (3): 534−535. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombay741977bomb/page/534 .

^ Gmelin, J. F. (1789). “Lacerta gangetica ” (ラテン語). Caroli a Linné. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis [Carol Linné. The System of Nature by the three Kingdoms of Nature: according to classes, orders, genera, species with characteristics, differences, synonyms, places] . ((Tomus I. Pars III)) . Leipzig: G. E. Beers. pp. 1057–1058. https://archive.org/details/carolilinns01linn/page/1057 ^ Linnaeus, C. (1758). “Lacerta” (ラテン語). Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis . ((Tomus I)) (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 41−42. https://archive.org/stream/mobot31753000798865#page/200/mode/2up ^ a b c 青木良輔 「素早く魚を捕らえる インドガビアル」『週刊朝日百科 動物たちの地球 両生類・爬虫類5 リクガメ・ワニほか』第5巻 101号著、朝日新聞社 、1992年 、150-152頁。

^ a b c d e 松井孝爾 「インドガビアル」『原色ワイド図鑑3 動物』今泉吉典、松井孝爾監修、学習研究社 、1984年 、151、184頁。

^ a b c d 長坂拓也 「インドガビアル」『爬虫類・両生類800種図鑑 第3版』千石正一監修 長坂拓也編著、ピーシーズ、2002年 、159頁。

^ Bonnaterre, P. J. (1789). “Le Gavial ” (フランス語). Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature. Erpétologie [Encyclopedic and methodical plates of the three Kingdoms of Nature. Herpetology] . Paris: Chez Panckoucke. pp. 34–35. https://archive.org/details/tableauencyclo00bonn/page/34 ^ Schneider, J. G. T. (1801). “Longirostris ” (ラテン語). Historiae amphibiorum naturalis et literariae fasciculus secundus [Natural History of and Literature about the Amphibians] . Jena: F. Frommann. pp. 160–161. https://archive.org/details/historiaeamphibi02schn/page/160 ^ Daudin, F. M. (1802). “Le crocodile à bec étroit ou le grand Gavial [The straight-snouted crocodile or the great Gavial ”] (フランス語). Histoire Naturelle, Générale et Particulière des Reptiles; ouvrage faisant suit à l'Histoire naturelle générale et particulière, composée par Leclerc de Buffon; et rédigee par C.S. Sonnini, membre de plusieurs sociétés savantes . ((Tome 2)) . Paris: F. Dufart. pp. 393–396. https://archive.org/details/histoirenaturel121802daud/page/392 ^ Cuvier, G. (1807). “Sur les différentes espèces de crocodiles vivans et sur leurs caractères distinctifs [About the different species of the living crocodiles and their distinct characteristics]” (フランス語). Annales du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle 10 : 8–66. https://archive.org/details/annalesdumusum10mus/page/66 . ^ Oppel, N. M. (1811). “Familia . Crocodilini” (ドイツ語). Die Ordnungen, Familien und Gattungen der Reptilien als Prodrom einer Naturgeschichte derselben . München: J. Lindauer. p. 19. https://archive.org/details/dieordnungenfami00oppe/page/19 ^ Wagler, J. (1830). “Rhamphostoma ” (ドイツ語). Natürliches System der Amphibien, mit vorangehender Classification der Säugethiere und Vögel. Ein Beitrag zur vergleichenden Zoologie [A natural System of the Amphibiae, preceded by a Classification of the Mammalia and Birds. A contribution to comparative Zoology] . München: J. G. Cotta'scche Buchhandlung. p. 141. https://archive.org/details/natrlichessystem00wagl/page/141 ^ Adams, A. (1854). “II. Order – Emydosaurians (Emydosauria)” . In Adams, A.; Baikie, W. B.; Barron, C.. A Manual of Natural History, for the Use of Travellers: Being a Description of the Families of the Animal and Vegetable Kingdoms: with Remarks on the Practical Study of Geology and Meteorology . London: John Van Voorst. pp. 70–71. https://books.google.com/books?id=71FAAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA70 ^ Günther, A. (1864). “Gavialis , Geoffr.” . The reptiles of British India . London: Robert Hardwicke. p. 63. https://archive.org/details/reptilesofbritis00gn/page/63 ^ Lydekker, R. (1886). “Gharialis hysudricus ” . Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India . Indian Tertiary and post Tertiary Vertebrata. III . Calcutta: Geological Survey Office. pp. 222–223. https://archive.org/details/indiantertiarypo03foot/page/222/mode/2up ^ Martin, J. E. (2018). “The taxonomic content of the genus Gavialis from the Siwalik Hills of India and Pakistan” . Papers in Palaeontology 5 (3): 483–497. Bibcode : 2019PPal....5..483M . doi :10.1002/spp2.1247 . https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02123647/file/2019Gavialis.pdf . ^ Brochu, C. A. (1997). “Morphology, fossils, divergence timing, and the phylogenetic relationships of Gavialis ”. Systematic Biology 46 (3): 479–522. doi :10.1093/sysbio/46.3.479 . PMID 11975331 . ^ Kälin, J. A. (1931). “Über die Stellung der Gavialiden im System der Crocodilia [On the position of the Gavialids in the system of the Crocodilia]” . Revue Suisse de Zoologie 38 (3): 379–388. https://archive.org/details/revuesuissedezoo3819schw/page/n451/mode/2up . ^ Hecht, M. K.; Malone, K. (1972). “On the Early History of the Gavialid Crocodilians”. Herpetologica 28 (3): 281–284. JSTOR 3890639 . ^ Densmore III, L. D. & Dessauer, H. C. (1984). “Low levels of protein divergence detected between Gavialis and Tomistoma : evidence for crocodilian monophyly?”. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Comparative Biochemistry 77 (4): 715–720. doi :10.1016/0305-0491(84)90302-X . ^ Frey, E.; Riess, J. & Tarsitano, S. F. (1989). “The axial tail musculature of recent crocodiles and its phyletic implications” . American Zoologist 29 (3): 857–862. doi :10.1093/icb/29.3.857 . https://academic.oup.com/icb/article-pdf/29/3/857/831972/29-3-857.pdf . ^ Gatesy, J. & Amato, G. D. (1992). “Sequence Similarity of 12S Ribosomal Segment of Mitochondrial DNAs of Gharial and False Gharial”. Copeia 1992 (1): 241–243. doi :10.2307/1446560 . JSTOR 1446560 . ^ a b Harshman, J.; Huddleston, C. J.; Bollback, J. P.; Parsons, T. J.; Braun, M. J. (2003). “True and false gharials: A nuclear gene phylogeny of crocodylia”. Systematic Biology 52 (3): 386–402. doi :10.1080/10635150309323 . PMID 12775527 .

^ Willis, R. E.; McAliley, L. R.; Neeley, E. D. & Densmore Ld, L. D. (2007). “Evidence for placing the false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii ) into the family Gavialidae: Inferences from nuclear gene sequences”. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 43 (3): 787–794. Bibcode : 2007MolPE..43..787W . doi :10.1016/j.ympev.2007.02.005 . PMID 17433721 . ^ a b c Lee, M. S. Y.; Yates, A. M. (2018). “Tip-dating and homoplasy: reconciling the shallow molecular divergences of modern gharials with their long fossil record” . Proceedings of the Royal Society B 285 (1881). doi :10.1098/rspb.2018.1071 . PMC 6030529 . PMID 30051855 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6030529/ .

^ a b Delfino, M. & De Vos, J. (2010). “A revision of the Dubois crocodylians, Gavialis bengawanicus and Crocodylus ossifragus , from the Pleistocene Homo erectus beds of Java”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (2): 427. Bibcode : 2010JVPal..30..427D . doi :10.1080/02724631003617910 .

^ Patnaik, R. & Schleich, H. H. (1993). “Fossil crocodile remains from the Upper Siwaliks of India” . Mitteilungen der Bayerischen Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und historische Geologie (33): 91–117. https://archive.org/details/mitteilungenderb313319911993baye/page/90 . ^ a b Win Ko Ko & Platt, S. G. (2012). “Does the Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus ) survive in Myanmar?” . Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 32 (4): 14–16. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/News-153f3fd2.pdf#page=14 .

^ Martin, J. E.; Buffetaut, E.; Naksri, W.; Lauprasert, K. & Claude, J. (2012). “Gavialis from the Pleistocene of Thailand and its relevance for drainage connections from India to Java” . PLOS ONE 7 (9): e44541. Bibcode : 2012PLoSO...744541M . doi :10.1371/journal.pone.0044541 . PMC 3445548 . PMID 23028557 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3445548/ . ^ Martin, J. E. (2019). “The taxonomic content of the genus Gavialis from the Siwalik Hills of India and Pakistan” . Papers in Palaeontology 5 (3): 483–497. Bibcode : 2019PPal....5..483M . doi :10.1002/spp2.1247 . https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02123647/file/2019Gavialis.pdf . ^ Gatesy, J. & Amato, G. (2008). “The rapid accumulation of consistent molecular support for intergeneric crocodylian relationships”. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 48 (3): 1232–1237. Bibcode : 2008MolPE..48.1232G . doi :10.1016/j.ympev.2008.02.009 . PMID 18372192 . ^ a b Erickson, G. M.; Gignac, P. M.; Steppan, S. J.; Lappin, A. K.; Vliet, K. A.; Brueggen, J. A.; Inouye, B. D.; Kledzik, D. et al. (2012). “Insights into the ecology and evolutionary success of crocodilians revealed through bite-force and tooth-pressure experimentation” . PLOS ONE 7 (3): e31781. Bibcode : 2012PLoSO...731781E . doi :10.1371/journal.pone.0031781 . PMC 3303775 . PMID 22431965 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3303775/ .

^ Hekkala, E.; Gatesy, J.; Narechania, A.; Meredith, R.; Russello, M.; Aardema, M. L.; Jensen, E.; Montanari, S. et al. (2021). “Paleogenomics illuminates the evolutionary history of the extinct Holocene "horned" crocodile of Madagascar, Voay robustus ” . Communications Biology 4 (1): 505. doi :10.1038/s42003-021-02017-0 . PMC 8079395 . PMID 33907305 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8079395/ . ^ a b c d Boulenger, G. A. (1889). “Gavialis ” . Catalogue of the Chelonians, Rhynchocephalians, and Crocodiles in the British Museum (Natural History) (New ed.). London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). pp. 275–276. https://archive.org/details/catalogueofchelo00brituoft/page/275

^ Boulenger, G. A. (1890). “Genus Gavialis ” . Fauna of British India. Reptilia and Batrachia . London: Taylor and Francis. p. 3. https://archive.org/details/reptiliabatrachi00boul/page/3 ^ a b Brazaitis, P. (1973). “Family Gavialidae Gavialis gangeticus Gmelin” . Zoologica 3 : 80−81. https://archive.org/details/zoologicascie58341973newy/page/80 .

^ a b c d 青木良輔 「インドガビアル」『動物世界遺産 レッド・データ・アニマルズ4 インド、インドシナ』小原秀雄・浦本昌紀・太田英利・松井正文編著、講談社 、2000年 、198頁。

^ a b c d e f g h i j Whitaker, R.; Members of the Gharial Multi-Task Force; Madras Crocodile Bank (2007). “The Gharial: Going Extinct Again” . Iguana 14 (1): 24–33. オリジナル の2011-07-26時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20110726191641/http://www.ircf.org/downloads/Iguana14_1%20Gharial%20Going%20Extinct%20Again.pdf .

^ Biswas, S.; Acharjyo, L. N. & Mohapatra, S. (1977). “A note on the protuberance or knob on the snout of male gharial, Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin)” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 74 (3): 536–537. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombay741977bomb/page/536 . ^ Hone, D.; Mallon, J.C.; Hennessey, P. & Witmer, L.M. (2020). “Ontogeny of a sexually selected structure in an extant archosaur Gavialis gangeticus (Pseudosuchia: Crocodylia) with implications for sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs” . PeerJ 8 : e9134. doi :10.7717/peerj.9134 . PMC 7227661 . PMID 32435543 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7227661/ . ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Whitaker, R. & Basu, D. (1982). “The Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus ): A review” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 79 (3): 531–548. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48239318#page/584/mode/1up .

^ Gauthier, J. A.; Nesbitt, S. J.; Schachner, E. R.; Bever, G. S. & Joyce, W. G. (2011). “The bipedal stem crocodilian Poposaurus gracilis : inferring function in fossils and innovation in archosaur locomotion” . Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History 52 (1): 107–126. doi :10.3374/014.052.0102 . https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229181586 . ^ a b c d e Maskey, T. M. & Percival, H. F. (1994). “Status and Conservation of Gharial in Nepal” . Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 12th Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group convened at Pattaya, Thailand, 2–6 May 1994 . Gland: IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group. pp. 77–83. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/12th-634937f9.pdf#page=90

^ Pitman, C. R. S. (1925). “The length attained by and the habits of the Gharial (G. gangeticus )” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 30 (3): 703. https://archive.org/details/journalofbomb30341925bomb/page/703 . ^ Flower, S. S. (1914). “The Gharial, Garialis gangeticus ” . Report on a zoological mission to India in 1913 . Cairo: Ministry of Public Works. p. 21. https://archive.org/details/flowerzoologicalmissi1913/page/20/mode/2up ^ Francis, R. (1911). “The broad snouted Mugger in the Indus” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 20 (4): 11601162. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombayn20191011bomb/page/1160/mode/2up . ^ Rao, C. J. (1933). “Gavial on the Indus”. Journal of the Sind Natural History Society 1 (4): 37. ^ Bustard, H. R. & Choudhury, B. C. (1983). “The distribution of the Gharial” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 79 (2): 427–429. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombay791982bomb/page/428 . ^ Biswas, S. (1970). “A Preliminary Survey of the Gharial in the Kosi River”. Indian Forester 96 (9): 705–710. ^ Macdonald, A. S. J. (1944). “Circumventing the Mahseer and Other Sporting Fish in India. Part VI: Mahseer Fishing in Assam and the Dooars” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 44 (3): 322–354. https://archive.org/details/journalofbo4419431944bomb/page/322/mode/2up . ^ Choudhury, A. U. (1997). “Records of the gharial Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin) from the Barak river system of north-eastern India” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 94 (1): 162–164. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombay941997bomb/page/162 . ^ Barton, C. G. (1929). “The Occurrence of the Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus ) in Burma” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 33 (2): 450–451. https://archive.org/details/journalofbomb33121929bomb/page/450/mode/2up . ^ a b Bashyal, A.; Shrestha, S.; Luitel, K.P.; Yadav, B.P.; Khadka, B.; Lang, J.W. & Densmore, L.D. (2021). “Gharials (Gavialis gangeticus ) in Bardiya National Park, Nepal: Population, habitat and threats”. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 31 (9): 2594–2602. Bibcode : 2021ACMFE..31.2594B . doi :10.1002/aqc.3649 .

^ Priol, P. (2003). Gharial field study report (Report). Kathmandu: Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation. ^ a b Ballouard, J. M.; Priol, P.; Oison, J.; Ciliberti, A. & Cadi, A. (2010). “Does reintroduction stabilize the population of the critically endangered gharial (Gavialis gangeticus , Gavialidae) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal?” . Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 20 (7): 756–761. Bibcode : 2010ACMFE..20..756B . doi :10.1002/aqc.1151 . https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227989979 .

^ Thapa, G. J.; Thapa, K.; Thapa, R.; Jnawali, S. R.; Wich, S. A.; Poudyal, L. P. & Karki, S. (2018). “Counting crocodiles from the sky: monitoring the critically endangered gharial (Gavialis gangeticus ) population with an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)”. Journal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems 6 (2): 71–82. doi :10.1139/juvs-2017-0026 . hdl :1807/87439 ^ Chowfin, S. (2010). “Crocodilian and freshwater research and conservation project, Uttarakhand, India” . Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 29 (3): 19. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/CSG%20-4575e7bc.pdf . ^ Chowfin, S. M. & Leslie, A. J. (2013). “A preliminary investigation into nesting and nest predation of the critically endangered, gharial (Gavialis gangeticus ) at Boksar in Corbett Tiger Reserve, Uttarakhand, India” . World Crocodile Conference. Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group . Gland: IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group. pp. 26−28. http://www.hwctf.org/Proceedings%20of%20the%2022nd%20Working%20Meeting%20of%20the%20IUCN-SSC%20Crocodile%20Specialist%20Group.pdf#page=27 ^ Chowfin, S. M. & Leslie, A. J. (2016). “The Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus ) in Corbett Tiger Reserve” . In Crocodile Specialist Group. Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 24th Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group in Skukuza, South Africa, 23–26 May 2016 . Gland: IUCN. pp. 120–124. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/cbb669b854f5d9b31438d0eca189915e.pdf#page=121 ^ Yadav, S. K.; Nawab, A. & Afifullah Khan, A. (2013). “Conserving the Critically Endangered Gharial Gavialis gangeticus in Hastinapur Wildlife Sanctuary, Uttar Pradesh: Promoting better coexistence for conservation” . World Crocodile Conference. Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group . Gland: IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group. pp. 78−82. http://www.hwctf.org/Proceedings%20of%20the%2022nd%20Working%20Meeting%20of%20the%20IUCN-SSC%20Crocodile%20Specialist%20Group.pdf#page=79 ^ “An endangered apex predator returns to the Ganga River ” (英語). World Wildlife Fund . 15 August 2023 閲覧。 ^ a b Rao, R. J. & Choudhury, B. C. (1992). “Sympatric distribution of gharial and mugger in India” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 89 : 312–315. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombay891992bomb/page/312 .

^ Das, A.; Basu, D.; Converse, L. & Choudhury, S. C. (2012). “Herpetofauna of Katerniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary, Uttar Pradesh, India”. Journal of Threatened Taxa 4 (5): 2553–2568. doi :10.11609/JoTT.o2587.2553-68 . ^ Vashistha, G.; Mungi, N.A.; Lang, J.W.; Ranjan, V.; Dhakate, P.M.; Khudsar, F.A. & Kothamasi, D. (2021). “Gharial nesting in a reservoir is limited by reduced river flow and by increased bank vegetation” . Scientific Reports 11 (1): 4805. Bibcode : 2021NatSR..11.4805V . doi :10.1038/s41598-021-84143-7 . PMC 7910305 . PMID 33637782 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7910305/ . ^ Choudhary, S. K. (2010). Multi-species Survey in River Gandak, Bihar with focus on Gharial and Ganges River Dolphin . https://www.academia.edu/10105543 ^ Choudhury, B. C.; Behera, S. K.; Sinha, S. K. & Chandrashekar, S. (2016). “Restocking, Monitoring, Population Status, New Breeding Record and Conservation Actions for Gharial in the Gandak River, Bihar, India” . In Crocodile Specialist Group. Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 24th Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group in Skukuza, South Africa, 23-26 May 2016 . Gland: IUCN. pp. 124. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/cbb669b854f5d9b31438d0eca189915e.pdf#page=125 ^ Hussain, S. A. (1999). “Reproductive success, hatchling survival and rate of increase of gharial Gavialis gangeticus in National Chambal Sanctuary, India”. Biological Conservation 87 (2): 261−268. Bibcode : 1999BCons..87..261A . doi :10.1016/S0006-3207(98)00065-2 . ^ a b Nawab, A.; Basu, D. J.; Yadav, S. K. & Gautam, P. (2013). “Impact of Mass Mortility of Gharial Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin, 1789) on its Conservation in the Chambal River in Rajasthan”. In Sharma, B. K.. Faunal Heritage of Rajasthan, India . Springer International Publishing. pp. 221–229. doi :10.1007/978-3-319-01345-9_9 . ISBN 978-3-319-01344-2

^ Rao, R. J.; Tagor, S.; Singh, H. & Dasgupta, N. (2013). “Monitoring of Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus ) and its habitat in the National Chambal Sanctuary, India” . World Crocodile Conference. Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group . Gland: IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group. pp. 66−73. http://www.hwctf.org/Proceedings%20of%20the%2022nd%20Working%20Meeting%20of%20the%20IUCN-SSC%20Crocodile%20Specialist%20Group.pdf#page=67 ^ a b Khandal, D.; Sahu, Y. K.; Dhakad, M.; Shukla, A.; Katdare, S. & Lang, J. W. (2017). “Gharial and Mugger in upstream tributaries of the Chambal River, north India” . Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 36 (4): 11–16. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/0add0eef2e93114c16d6db73f1a9aab3.pdf .

^ Nair, T. (2012). “Gharial hatchlings in the Yamuna” . Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 32 (4): 17. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/News-153f3fd2.pdf#page=17 . ^ a b Nair, T. & Katdare, S. (2013). “Dry-season assessment of gharials (Gavialis gangeticus ) in the Betwa, Ken and Son Rivers, India” . World Crocodile Conference. Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group . Gland: IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group. pp. 53−65. http://www.hwctf.org/Proceedings%20of%20the%2022nd%20Working%20Meeting%20of%20the%20IUCN-SSC%20Crocodile%20Specialist%20Group.pdf#page=54

^ Nair, T.; Dey, S. & Gupta, S. P. (2019). “Relicts in the River: Short Survey for Gharials (Gavialis gangeticus ) in the Kosi River, India” . Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 38 (4): 11–14. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/088e46b7001f85854cb7d30b1c90b743.pdf#page=11 . ^ Bustard, H. R. (1983). “Movement of wild Gharial, Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin) in the River Mahanadi, Orissa (India)”. British Journal of Herpetology 6 : 287–291. ^ Mohanty, B.; Nayak, S. K.; Panda, B.; Mitra, A. & Pattanaik, S. K. (2010). “Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus ) in the Mahanadi River system of Orissa, India: On the brink of extinction”. E-planet 8 (8): 49–52. ^ Choudhury, A. U. (1998). “Status of the gharial Gavialis gangeticus in the main Brahmaputra river” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 95 (1): 118–120. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombay941997bomb/page/162 . ^ Saikia, B. P. (2010). “Indian Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus ): Status, ecology and conservation” . In Singaravelan, N.. Rare Animals of India . Sharjah: Bentham Science Publishers. pp. 76–100. ISBN 9781608054855 . https://books.google.com/books?id=BUPcAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA76 ^ Hasan, K. & Alam, S. (2016). “Chapter 3: Findings” . Gharials of Bangladesh . Dhaka: IUCN Bangladesh Country Office. pp. 29–65. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326981894 ^ Lang, J. W. (1987). “Crocodilian behaviour: implications for management”. In Webb, G. J. W.; Manolis, S. C.; Whitehead, P. J.. Wildlife Management: Crocodiles and Alligators . Sydney: Surrey Beatty and Sons. pp. 273−294 ^ a b c Lang, J. W. & Kumar, P. (2013). “Behavioral ecology of Gharial on the Chambal River, India” . World Crocodile Conference. Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group . Gland: IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group. pp. 42−52. http://www.hwctf.org/Proceedings%20of%20the%2022nd%20Working%20Meeting%20of%20the%20IUCN-SSC%20Crocodile%20Specialist%20Group.pdf#page=43

^ Rao, R. J. & Choudhury, B. C. (1992). “Sympatric distribution of Gharial Gavialis gangeticus and Mugger Crocodylus palustris in India” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 89 (3): 313–314. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombay891992bomb/page/312 . ^ Choudhary, S.; Choudhury, B. C. & Gopi, G. V. (2018). “Spatio-temporal partitioning between two sympatric crocodilians (Gavialis gangeticus & Crocodylus palustris ) in Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary, India” . Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 28 (5): 1067–1076. Bibcode : 2018ACMFE..28.1067C . doi :10.1002/aqc.2911 . https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325692895 . ^ Whitaker, R. & Whitaker, Z. (1989). “Ecology of the mugger crocodile” . Crocodiles, their ecology, management, and conservation . Gland: IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group. pp. 276–296. https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/NS-1989-001.pdf ^ Forsyth, H. W. (1914). “The food of Crocodiles” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 23 (1): 228–229. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombayn20191011bomb/page/228/mode/2up . ^ Bustard, H. R. & Maharana, S. (1983). “Size at first breeding in the Gharial [Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin) (Reptilia, Crocodilia) in captivity”]. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 79 (1): 206−207. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombay791982bomb/page/206 . ^ Martin, B. G. H. & Bellairs, A. d'A. (1977). “The narial excrescence and pterygoid bulla of the gharial, Gavialis gangeticus (Crocodilia)”. Journal of Zoology 182 (4): 541–558. doi :10.1111/j.1469-7998.1977.tb04169.x . ^ Bustard, H. R. & Basu, S. (1983). “A record (?) Gharial clutch” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 79 (1): 207−208. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombay791982bomb/page/207 . ^ Smith, M. A. (1931). “Gavialis ” . The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Reptilia and Amphibia . ((I. Loricata, Testudines)) . London: Secretary of State for India in Council. pp. 37–40. https://archive.org/details/FBISmithReptiles1/page/n63 ^ Bustard, H. R. (1982). “Behaviour of the male Gharial during the nesting and post-hatching period” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 79 (3): 677–680. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombay791982bomb/page/530 . ^ Lang, J. W. & Kumar, P. (2016). “Chambal Gharial Ecology Project – 2016 Update” . In Crocodile Specialist Group. Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 24th Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group Skukuza, South Africa, 23-26 May 2016 . Gland: IUCN. pp. 136–148. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/cbb669b854f5d9b31438d0eca189915e.pdf#page=137 ^ Khadka, B. B. & Bashyal, A. (2019). “Growth rate of captive Gharials Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin, 1789) (Reptilia: Crocodylia: Gavialidae) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal”. Journal of Threatened Taxa 11 (15): 14998–15003. doi :10.11609/jott.5491.11.15.14998-15003 . ^ Hussain, S. A. (2009). “Basking site and water depth selection by Gharial Gavialis gangeticus Gmelin 1789 (Crocodylia, Reptilia) in National Chambal Sanctuary, India and its implication for river conservation”. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 19 (2): 127–133. Bibcode : 2009ACMFE..19..127H . doi :10.1002/aqc.960 . ^ Whitaker, R.; Basu, D. & Huchzermeyer, F. (2008). “Update on gharial mass mortality in National Chambal Sanctuary” . Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 27 (1): 4–8. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/CSG%20-8d303c03.pdf . ^ Katdare, S. (2011). “Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus ) populations and human influences on habitat on the River Chambal, India”. Aquatic Conservation 21 (4): 364–371. Bibcode : 2011ACMFE..21..364K . doi :10.1002/aqc.1195 . ^ Bustard, H. R. (1999). “Indian Crocodile Conservation Project” . Envis Wildlife and Protected Areas 2 (1): 5–9. https://archive.org/details/IndianCrocodilians/page/n9 . ^ Singh, A.; Singh, R. L. & Basu, D. (1999). “Conservation Status of the Gharial in Uttar Pradesh” . Envis Wildlife and Protected Areas 2 (1): 91–94. https://archive.org/details/IndianCrocodilians/page/n91/mode/2up . ^ Stevenson, C. J. (2015). “Conservation of the Indian Gharial Gavialis gangeticus : successes and failures”. International Zoo Yearbook 49 (1): 150–161. doi :10.1111/izy.12066 . ^ a b Lang, J. W. (2017). “Doing the Needful in Nepal: Priorities of Gharial Conservation” . Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 36 (2): 9–12. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/f6c68866824331a45008304911496a1d.pdf .

^ Khadka, B. B. (2018). “119 Juvenile Gharials released into the Rapti River, Chitwan National Park, Nepal” . Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 37 (1): 12−13. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/9165a6d4d4d38607adc3b1e8b9e93c5e.pdf . ^ Acharya, K. P.; Khadka, B. K.; Jnawali, S. R.; Malla, S.; Bhattarai, S.; Wikramanayake, E. & Köhl, M. (2017). “Conservation and population recovery of Gharials (Gavialis gangeticus ) in Nepal”. Herpetologica 73 (2): 129–135. doi :10.1655/HERPETOLOGICA-D-16-00048.1 . ^ Katdare, S.; Srivathsa, A.; Joshi, A.; Panke, P.; Pande, R.; Khandal, D. & Everard, M. (2011). “Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus ) populations and human influences on habitat on the River Chambal, India”. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 21 (4): 364–371. Bibcode : 2011ACMFE..21..364K . doi :10.1002/aqc.1195 . ^ Nair, T.; Thorbjarnarson, J. B.; Aust, P. & Krishnaswamy, J. (2012). “Rigorous gharial population estimation in the Chambal: implications for conservation and management of a globally threatened crocodilian”. Journal of Applied Ecology 49 (5): 1046–1054. Bibcode : 2012JApEc..49.1046N . doi :10.1111/j.1365-2664.2012.02189.x . ^ Webb, G. (2018). “Editorial” . Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 37 (1): 3−4. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/9165a6d4d4d38607adc3b1e8b9e93c5e.pdf . ^ “Sighting of extinct Gharial signals hope for species revival ”. The Express Tribune (May 15, 2023). 2024年7月4日 閲覧。 ^ “Gharials in Pakistan- what we know so far ”. www.wwfpak.org . 2024年7月4日 閲覧。 ^ “Monitoring and assessment of gharial conservation initiatives ”. wwf.panda.org . 2024年7月4日 閲覧。 ^ Vashistha, G.; Lang, J.W.; Dhakate, P.M. & Kothamasi, D. (2021). “Sand addition promotes gharial nesting in a regulated river-reservoir habitat”. Ecological Solutions and Evidence 2 (2): e12068. Bibcode : 2021EcoSE...2E2068V . doi :10.1002/2688-8319.12068 . ^ Choudhury, B. C. (1999). “Crocodile Breeding in Indian Zoos” . Envis Wildlife and Protected Areas 2 (1): 100–103. https://archive.org/details/IndianCrocodilians/page/n101 . ^ Ziegler, T. (2018). “Europe” . In Crocodile Specialist Group. Crocodile Specialist Group Steering Committee Meeting, Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Santa Fe, Argentina (6 May 2018) . Santa Fe, Argentina. pp. Agenda Item: SC. 2.7. http://www.iucncsg.org/content_images/SantaFe/SC.2.7.%20Europe.pdf ^ Fougeirol, L. (2009年). “Le gavial du Gange, un rêve オリジナル よりアーカイブ。2017年12月26日 閲覧。 ^ Bronx Zoo (2017年). “Indian Gharials return to the Zoo ”. Wildlife Conservation Society . 2024年7月4日 閲覧。 ^ “L.A. Zoo Becomes One of Nine Zoos in the Western Hemisphere to House Gharials Flown in from India ”. Los Angeles Zoo and Botanical Gardens (2017年). 2020年10月25日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2018年10月29日 閲覧。 ^ NBCDFW Staff and Alicia Barrera (2023年). “Fort Worth Zoo announces 'groundbreaking births' of endangered gharial crocodiles ”. NBCDFW . 2024年7月4日 閲覧。 ^ 特定動物リスト (動物の愛護と適切な管理) (環境省 ・2015年12月10日に利用)^ Verma, S. P. (2016). “Part II. Depictions of Natural History, Figure 11” . The Illustrated Baburnama . Oxon: Routledge. p. Figure 11. ISBN 9781317338628 . https://books.google.com/books?id=G4GPCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT491 ^ Parpola, A. (2011). “Crocodile in the Indus Civilization and later South Asian traditions” . In Osada, H.; Endo, H.. Linguistics, Archaeology and the Human Past . Kyoto, Japan: Indus Project Research Institute for Humanity and Nature. pp. 1–57. ISBN 978-4-902325-67-6 . https://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Parpola_Asko_2011._Crocodile_in_the_Indu.pdf ^ Vyas, R. (2018). “Gharial Motifs (Gavialis gangeticus ) at Sanchi Stupa, India” . Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 37 (4): 13. http://www.iucncsg.org/365_docs/attachments/protarea/3ab6597756810d7ab30707a91943b1f3.pdf#page=13 . ^ Behera, S. K.; Singh, H. & Sagar, V. (2014). “Indicator Species (Gharial and Dolphin) of Riverine Ecosystem: An Exploratory of River Ganga” . In Sanghi, R.. Our National River Ganga: Lifeline of Millions . Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. pp. 103–123. doi :10.1007/978-3-319-00530-0_4 . ISBN 978-3-319-00529-4 . https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287563244 ^ Babur, Z. M. (1922). “Fauna of Hindustan: Aquatic animals” (チャガタイ語). Babur-nama [The Memoirs of Babur] . 2 . London: Luzac and Co. pp. 501–503. https://archive.org/details/baburnamainengli02babuuoft/page/502 ^ Lowis, R. M. (1915). “Gharial, Gavialis gangeticus , and Porpoise, Platanista gangetica , catching in the Indus” . Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 23 (4): 779. https://archive.org/details/journalofbombayn231914bomb/page/779/mode/1up . ^ Maskey, T. M. & Mishra, H. R. (1982). “Conservation of gharial (Gavialis gangeticus ) in Nepal”. In Majupuria, T. C.. Wild is beautiful: Introduction to the magnificent, rich and varied fauna and wildlife of Nepal . Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh: Lashkar S. Devi. pp. 185–196

ウィキメディア・コモンズには、

インドガビアル に関連するメディアがあります。