|

Wulfstan (died 1023)

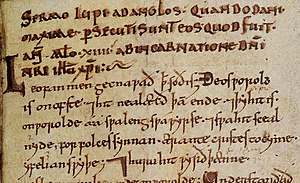

Wulfstan (sometimes Wulfstan II[1] or Lupus;[2] died 28 May 1023) was an English Bishop of London, Bishop of Worcester, and Archbishop of York. He is thought to have begun his ecclesiastical career as a Benedictine monk. He became the Bishop of London in 996. In 1002 he was elected simultaneously to the diocese of Worcester and the archdiocese of York, holding both in plurality until 1016, when he relinquished Worcester; he remained archbishop of York until his death. It was perhaps while he was at London that he first became well known as a writer of sermons, or homilies, on the topic of Antichrist. In 1014, as archbishop, he wrote his most famous work, a homily which he titled the Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, or the Sermon of the Wolf to the English. Besides sermons Wulfstan was also instrumental in drafting law codes for both kings Æthelred the Unready and Cnut the Great of England.[3] He is considered one of the two major writers of the late Anglo-Saxon period in England. After his death in 1023, miracles were said to have occurred at his tomb, but attempts to have him declared a saint never bore fruit. LifeWulfstan's early life is obscure, but he was certainly the uncle of one Beorhtheah, his successor at Worcester but one, and the uncle of Wulfstan of Worcester.[4][5] About Wulfstan's youth we know nothing. He probably had familial ties to the Fenlands in East Anglia,[6] and to Peterborough specifically.[7] Although there is no direct evidence of his ever being monastic, the nature of Wulfstan's later episcopal career and his affinity with the Benedictine Reform argue that he had once studied and professed as a Benedictine monk, perhaps at Winchester.[8][9][a] According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Wulfstan was consecrated bishop of London in 996, succeeding Aelfstan.[10] Besides the notice in the Chronicle, the first record of his name is in a collection of nine Latin penitential letters collected by him,[b] three of which were issued by him as bishop of London, and one by him as "Archbishop of the English". The other five letters in the collection (only one of which is addressed to Wulfstan, as archbishop) were issued by Pope Gregory V and by a Pope John (either Pope John XVII or Pope John XVIII). In the letters issued by Wulfstan as bishop of London he styles himself "Lupus episcopus", meaning "the bishop Wolf."[11] "Lupus" is the Latin form of the first element of his Old English name, which means "wolf-stone."[12] In 1002 Wulfstan was elected Archbishop of York and was immediately translated to that see.[c] Holding York also brought him control over the diocese of Worcester, as at that time it was practice in England to hold "the potentially disaffected northern archbishopric in plurality with a southern see."[14][d] He held both Worcester and York until 1016, resigning Worcester to Leofsige while retaining York.[15] There is evidence, however, that he retained influence over Worcester even after this time, and that Leofsige perhaps acted "only as a suffragan to Wulfstan."[16] Although holding two or more episcopal sees in plurality was both uncanonical and against the spirit of the Benedictine Reform, Wulfstan had inherited this practice from previous archbishops of York, and he was not the last to hold York and Worcester in plurality.[17][e] Wulfstan must have early on garnered the favour of powerful men, particularly Æthelred king of England, for we find him personally drafting all royal law codes promulgated under Æthelred's reign from 1005 to 1016.[18] There is no doubt that Wulfstan had a penchant for law; his knowledge of previous Anglo-Saxon law (both royal and ecclesiastical), as well as ninth-century Carolingian law, was considerable. This surely made him a suitable choice for the king's legal draftsman. But it is also likely that Wulfstan's position as archbishop of York, an important centre in the then politically sensitive northern regions of the English kingdom, made him not only a very influential man in the North, but also a powerful ally for the king and his family in the South. It is indicative of Wulfstan's continuing political importance and savvy that he also acted as legal draftsman for, and perhaps advisor to, the Danish king Cnut, who took England's West Saxon throne in 1016.[18] Homilist Wulfstan was one of the most distinguished and effective Old English prose writers.[19][20] His writings cover a wide range of topics in an even greater range of genres, including homilies (or sermons), secular laws, religious canons, and political theory. With Ælfric of Eynsham, he is one of the two major vernacular writers in early eleventh-century England, a period which, ecclesiastically, was still very much enamoured of and greatly influenced by the Benedictine Reform. The Benedictine Reform was a movement which sought to institute monastic standards among the secular clergy, a movement made popular by the churchmen of the Carolingian Empire in the ninth and tenth centuries. The Reform promoted a regular (i.e. based on a regula, or rule) life for priests and clerics, a strict church hierarchy, the primacy of the Roman see, the authority of codified or canonical church law, and stressed the importance of catholic, that is universal, church practices throughout all Christendom. These ideas could only thrive in a social and political atmosphere which recognised the importance of both the clergy's and the laity's obedience to the authority of the church on all things spiritual, and also on many things secular and juridical. This was one of the main theoretical models behind much of Wulfstan's legal and quasi-legal writings. But Wulfstan was not blind to the fact that, in order for this Reform model to thrive in England, the English clergy and laity (especially the laity) needed to be educated in the basic tenets of the faith. Nothing less than the legitimacy of English Christendom rested on Englishmen's steadfastness on certain fundamental Christian beliefs and practices, like, for example, knowledge of Christ's life and passion, memorisation of the Pater Noster and the Apostles' Creed, proper baptism, and the correct date and method of celebrating Easter mass. It is towards the promotion of such beliefs and practices, that Wulfstan engaged in writing a number of homilies dedicated to educating both clergy and laity in those Christian fundamentals which he saw as so important for both the flourishing of Christian lives and the success of the English polity.[21] In a series of homilies begun during his tenure as Bishop of London, Wulfstan attained a high degree of competence in rhetorical prose, working with a distinctive rhythmical system based around alliterative pairings. He used intensifying words, distinctive vocabulary and compounds, rhetorical figures, and repeated phrases as literary devices. These devices lend Wulfstan's homilies their tempo-driven, almost feverish, quality, allowing them to build toward multiple climaxes. An example from one of his earliest sermons, titled Secundum Lucam, describes with vivid rhetorical force the unpleasantries of Hell (notice the alliteration, parallelism, and rhyme): Wa þam þonne þe ær geearnode helle wite. Ðær is ece bryne grimme gemencged, & ðær is ece gryre; þær is granung & wanung & aa singal heof; þær is ealra yrmða gehwylc & ealra deofla geþring. Wa þam þe þær sceal wunian on wite. Betere him wære þæt he man nære æfre geworden þonne he gewurde.[22]

This type of heavy-handed, though effective, rhetoric immediately made Wulfstan's homilies popular tools for use at the pulpit.[24] There is good evidence that Wulfstan's homiletic style was appreciated by his contemporaries. While yet bishop of London, in 1002 he received an anonymous letter in Latin praising his style and eloquence. In this letter, an unknown contemporary refuses to do a bit of translation for Wulfstan because he fears he could never properly imitate the Bishop's style.[2] The Chronicle of Ely said of his preaching that "when he spoke, it was as if his listeners were hearing the very wisdom of God Himself."[25] Though they were rhetorically ornate, Wulfstan's homilies show a conscious effort to avoid the intellectual conceits presumably favoured by educated (i.e. monastic) audiences; his target audience was the common English Christian, and his message was suited to everyone who wished to flock to the cathedral to hear it. Wulfstan refused to include in his works confusing or philosophical concepts, speculation, or long narratives – devices which other homilies of the time regularly employed (likely to the dismay of the average parishioner). He also rarely used Latin phrases or words, though a few of his homilies do survive in Latin form, versions that were either drafts for later English homilies, or else meant to be addressed to a learned clergy. Even so, even his Latin sermons employ a straightforward approach to sermonising. Wulfstan's homilies are concerned only with the "bare bones, but these he invests with a sense of urgency of moral or legal rigorism in a time of great danger".[26] The canon of Wulfstan's homiletic works is somewhat ambiguous, as it is often difficult to tell if a homily in his style was actually written by Wulfstan, or is merely the work of someone who had appreciated Wulfstanian style and imitated it. However, throughout his episcopal career, he is believed to have written upwards of 30 sermons in Old English. The number of his Latin sermons has not yet been established.[f] He may also have been responsible, wholly or in part, for other extant anonymous Old English sermons, for his style can be detected in a range of homiletic texts which cannot be directly attributed to him. However, as mentioned, some scholars believe that Wulfstan's powerful rhetorical style produced imitators, whose homilies would now be difficult to distinguish from genuine Wulfstanian homilies.[28] Those homilies which are certainly by Wulfstan can be divided into 'blocks', that is by subject and theme, and in this way it can be seen that at different points in his life Wulfstan was concerned with different aspects of Christian life in England.[29] The first 'block' was written ca. 996–1002 and is concerned with eschatology, that is, the end of the world. These homilies give frequent descriptions of the coming of Antichrist and the evils that will befall the world before Christ's Second Coming. They likely play on the anxiety that surely developed as the end of the first millennium AD approached. The second 'block', written around 1002–1008, is concerned with the tenets of the Christian faith. The third 'block', written around 1008–1020, concerns archiepiscopal functions. The fourth and final 'block', written around 1014–1023, known as the "Evil Days" 'block', concerns the evils that befall a kingdom and people who do not live proper Christian lives. This final block contains his most famous homily, the Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, where Wulfstan rails against the deplorable customs of his time, and sees recent Viking invasions as God's punishment of the English for their lax ways. About 1008 (and again in a revision about 1016) he wrote a lengthy work which, although not strictly homiletic, summarises many of the favourite points he had hitherto expounded upon in his homilies. Titled by modern editors as the Institutes of Polity, it is a piece of 'estates literature' which details, from the perspective of a Christian polity, the duties of each member of society, beginning with the top (the king) and ending at the bottom (common folk).[30] LanguageWulfstan was a native speaker of Old English. He was also a competent Latinist. As York was at the centre of a region of England that had for some time been colonised by people of Scandinavian descent, it is possible that Wulfstan was familiar with, or perhaps even bilingual in, Old Norse. He may have helped incorporate Scandinavian vocabulary into Old English. Dorothy Whitelock remarks that "the influence of his sojourns in the north is seen in his terminology. While in general he writes a variety of late West Saxon literary language, he uses in some texts words of Scandinavian origin, especially in speaking of the various social classes."[31] In some cases, Wulfstan is the only one known to have used a word in Old English, and in some cases such words are of Scandinavian origin. Some words of his that have been recognised as particularly Scandinavian are þræl "slave, servant" (cf. Old Norse þræll; cp. Old English þeowa), bonda "husband, householder" (cf. Old Norse bondi; cp. Old English ceorl), eorl "nobleman of high rank, (Danish) jarl" (cf. Old Norse jarl; cp. Old English ealdorman), fysan "to make someone ready, to put someone to flight" (cf. Old Norse fysa), genydmaga "close kinsfolk" (cf. Old Norse nauðleyti), and laga "law" (cf. Old Norse lag; cp. Old English æw)[g] Some Old English words which appear only in works under his influence are werewulf "were-wolf," sibleger "incest," leohtgescot "light-scot" (a tithe to churches for candles), tofesian, ægylde, and morðwyrhta Church reform and royal service Wulfstan was very involved in the reform of the English church, and was concerned with improving both the quality of Christian faith and the quality of ecclesiastical administration in his dioceses (especially York, a relatively impoverished diocese at this time). Towards the end of his episcopate in York, he established a small monastery in Gloucester, which had to be re-established in 1058 after being burned.[32] In addition to his religious and literary career, Wulfstan enjoyed a lengthy and fruitful career as one of England's foremost statesmen. Under both Æthelred II and Cnut, Wulfstan was primarily responsible for the drafting of English law codes relating to both secular and ecclesiastical affairs, and seems to have held a prominent and influential position at court.[2] He drew up the laws that Æthelred issued at Enham in 1008, which dealt with the cult of St Edward the Martyr, the raising and equipping of ships and ship's crews, the payment of tithes, and a ban on the export of (Christian) slaves from the kingdom.[33] Pushing for religious, social, political, and moral reforms, Wulfstan "wrote legislation to reassert the laws of earlier Anglo-Saxon kings and bring order to a country that had been unsettled by war and influx of Scandinavians."[34]  In 1009 Wulfstan wrote the edict that Æthelred II issued calling for the whole nation to fast and pray for three days during Thorkell's raids on England, in a national act of penance. Only water and bread were to be eaten, people should walk to church barefoot, a payment of one penny from each hide of land was to be made, and everyone should attend Mass every day of the three days. Anyone not participating would be fined or flogged.[35] After Cnut conquered England, Wulfstan quickly became an advisor to the new king, as evidenced by Wulfstan's influence on the law code issued by Cnut.[36] After the death of Lyfing, Archbishop of Canterbury in 1020, Wulfstan consecrated his successor Æthelnoth in 1020, and wrote to Cnut asking the king to grant the same rights and dignities for the new archbishop that previous archbishops had held.[37] Wulfstan also wrote the laws that were issued by Cnut at Winchester in 1021 or 1022.[2] These laws continued in force throughout the 11th century, as they were the laws referred to in Domesday Book as "the law of King Edward".[38] Death and legacyWulfstan died at York on 28 May 1023. His body was taken for burial to the monastery of Ely, in accordance with his wishes. Miracles are ascribed to his tomb by the Liber Eliensis, but it does not appear that any attempt to declare him a saint was made beyond this.[2] The historian Denis Bethell called him the "most important figure in the English Church in the reigns of Æthelred II and Cnut."[39] Wulfstan's writings influenced a number of writers in late Old English literature. There are echoes of Wulfstan's writings in the 1087 entry of the Peterborough Chronicle, a version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle written at Peterborough Abbey. This entry has long been famous as it deals with the death of King William the Conqueror, and contrasts his worldly power with his status after death.[40] Other suggestions of Wulfstan's writing occur in works of Old English, including the Soul's Address to the Body.[41] His law codes, which were written under Æthelred and Cnut, remained in effect through the reign of King Edward the Confessor, and were still being reaffirmed in 1100, when King Henry I of England swore a coronation oath to observe the laws of King Edward.[42] The unique 11th-century manuscript of the Early English Apollonius of Tyre may only have survived because it was bound into a book together with Wulfstan's homilies.[43] WorksWulfstan wrote some works in Latin, and numerous works in Old English, then the vernacular.[h] He has also been credited with a few short poems. His works can generally be divided into homiletic, legal, and philosophical categories. Wulfstan's best-known homily is Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, or Sermon of the Wolf to the English. In it he proclaims the depredations of the "Danes" (who were, at that point, primarily Norwegian invaders) a scourge from God to lash the English for their sins. He calls upon them to repent of their sinful ways and "return to the faith of baptism, where there is protection from the fires of hell."[34] He also wrote many homilies relating to the Last Days and the coming of the Antichrist.[8][44] Age of the Antichrist was a popular theme in Wulfstan's homilies, which also include the issues of death and Judgment Day. Six homilies that illustrate this theme include: Secundum Matheum, Secundum Lucam, De Anticristo, De Temporibus Antichrist, Secundum Marcum and "De Falsis Deis". De Antichristo was the "first full development of the Antichrist theme", and Wulfstan addressed it to the clergy.[45] Believing that he lived at the time right before the Antichrist was to come, he felt compelled to diligently warn and teach the clergy to withstand the dishonest teaching of the enemies of God.[46] These six homilies also include: emphasis that the hour of the Antichrist is very near, warnings that the English should be aware of false Christs who will attempt to seduce men, warnings that God will pass judgement on man's faithfulness, discussion of man's sins, evils of the world, and encouragement to love God and do his will.[47] He wrote the Canons of Edgar and The Law of Edward and Guthrum which date before 1008.[2] The Canons was written to instruct the secular clergy serving a parish in the responsibilities of their position. The Law of Edward and Guthrum, on the other hand, is an ecclesiastical law handbook.[48] Modern editors have paid most attention to his homilies: they have been edited by Arthur Napier,[49] by Dorothy Whitelock,[50] and by Dorothy Bethurum.[51] Since that publication, other works that were likely authored by Wulfstan have been identified; a forthcoming edition by Andy Orchard will update the canon of Wulfstan's homilies. Wulfstan was also a book collector; he is responsible for amassing a large collection of texts pertaining to canon law, the liturgy, and episcopal functions. This collection is known as Wulftan's Commonplace Book. A significant part of the Commonplace book consists of a work once known as the Excerptiones pseudo-Ecgberhti, though it has most recently been edited as Wulfstan's Canon Law Collection (a.k.a. Collectio canonum Wigorniensis).[52] This work is a collection of conciliar decrees and church canons, most of which he culled from numerous ninth and tenth-century Carolingian works. This work demonstrates the wide range of Wulfstan's reading and studies. He sometimes borrowed from this collection when he wrote his later works, especially the law codes of Æthelred.[53] There are also a number of works which are associated with the archbishop, but whose authorship is unknown, such as the Late Old English Handbook for the Use of a Confessor.[54] StyleWulfstan's style is admired by many sources, easily recognisable and exceptionally distinguished. "Much Wulfstan material is, more-over, attributed largely or even solely on the basis of his highly idiosyncratic prose style, in which strings of syntactically independent two-stress phrases are linked by complex patterns of alliteration and other kinds of sound play. Indeed, so idiosyncratic is Wulfstan’s style that he is even ready to rewrite minutely works prepared for him by Ǣlfric".[19] From this identifiable style, 26 sermons can be attributed to Wulfstan, 22 of which are written in Old English, the others in Latin. However, it's suspected that many anonymous materials are Wulfstan's as well, and his handwriting has been found in many manuscripts, supplementing or correcting material.[19] He wrote more than just sermons, including law-codes and sections of prose. Certainly he must have been a talented writer, gaining a reputation of eloquence while he still lived in London.[55] In a letter to him, "the writer asks to be excused from translating something Wulfstan had asked him to render into English and pleads as an excuse his lack of ability in comparison with the bishop’s skill".[55] Similarly, "[o]ne early student of Wulfstan, Einenkel, and his latest editor, Jost, agree in thinking he wrote verse and not prose" (Continuations, 229). This suggests Wulfstan's writing is not only eloquent, but poetic, and among many of his rhetorical devices is marked rhythm (229). Taking a look at Wulfstan's actual manuscripts, presented by Volume 17 of Early English Manuscripts in Facsimile, it becomes apparent that his writing was exceptionally neat and well structured – even his notes in the margins are well organised and tidy, and his handwriting itself is ornate but readable.[original research?] Notes

Citations

References

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||