|

Waste management in Australia

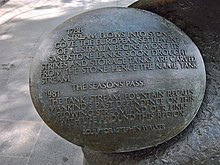

Waste management in Australia started to be implemented as a modern system by the second half of the 19th century, with its progresses driven by technological and sanitary advances.[2][3] It is currently regulated at both federal and state level.[4] The Commonwealth's Department of the Environment and Energy is responsible for the national legislative framework.[4] The waste management has different effects and applications depending on the geographical,[5] demographic[5] and behavioural[6] dynamics which it relates to. A number of reports and campaigns have been promoted. The system is undergoing a process of reformation to establish a more consistent and circular economy-based legislation,[6] a more reliable database[7] and a stronger, more independent domestic industry.[6] These factors have hampered the development of the industry and interstate relations.[5][6] Historical developmentPre-European settlementAboriginal middens are arrangements of bones, shells, ashes and other waste materials, usually related to meal consumption.[2][8][9] Most of them are considered as relics of cultural[8][10][11] and archaeological relevance.[11][12][13] Size can vary and they can occupy entire coastlines for hundreds of metres.[8] Middens have been described as the first forms of dumping sites in Australia.[2][14] Seashells became an important source of lime in the 1800s and so middens, for example in the Sutherland Shire area, may have been mined for shells.[15] Differences with western-like disposal areas derive from the middens' purpose.[2] Australian Indigenous people possess a culture which relates to land, sea and resources in a holistic way.[2][9] As such, middens were used to organise resources and were not intended to, and did not, damage the landscape.[2] Most Aborigines conducted a nomadic way of life,[16][17][18][dubious – discuss] and because they were those who moved, and not their "refuses",[17] some of these sites had originated from continuous human presence over hundreds or thousands of years.[8][10] The low density population, its ecological footprint and the traits of the Australian environment led to a harmonised system in which waste was not contemplated as, and did not represent, an issue.[17] 1788–1900 Sydney Cove became the place of the first permanent European settlement in Australia on 26 January 1788.[19][20] In accordance with a study, that is also considered the date in which the country's waste disposal system started to represent a problem.[3] The period spanning from 1788 to 1850 was characterised by an out-of-sight, out-of-mind mentality towards garbage and waste.[3][21] The concept was supported by the idea that the geography of Australia, and in particularly its vastness, would have allowed for an infinite time the exploitation of its areas as dumping sites.[3] In most of the cases, residents were asked to independently dispose of their own waste (which was mostly organic) and the general lack of regulations resulted in very low hygienic conditions.[2][3][22] These ultimately led to soil and water contamination, conditions that had consequences during the urban expansion in later years.[2][3][23] The initial absence of an industry that could have provided enough resources and materials for the colonies forced high rates of recycling.[2][3] Household and other early forms of waste that could not be recycled or otherwise reused were left in the streets, dumped in rivers, or collected in the backyard, where acid was used to accelerate decomposition and diminish the smell.[2] Diaries and journals from travellers and residents in the first decades of Sydney's life reported a "shameful situation",[3][24] which saw what at that time was a town of 50,000 people covered by various types of waste, flies and mosquitoes.[3] Sydney Harbour was the major dumping site.[3] Getting rid of waste in the sea (sea waste burial) was also a common practice,[3] and beaches were often covered by residuals brought by tides.[2]  The Gadigal clan, one of the original Sydney local communities,[25][26] used to collect freshwater in a river prior the European colonisation.[2][26] At the time of Captain Arthur Phillip looking for the ideal settlement site, in 1788, a primary requirement was that of a sufficient freshwater supply,[27] and that river constituted a crucial discriminant in the choice of Sydney.[20][27] After the arrival of the colonists, the stream has been reported to have become so polluted that it was ordered to be covered with sandstone.[2] The "Tank Stream", as it is now known, still flows beneath Sydney.[2][28] Dr Edwin Chadwick, with his publication "Treatise on Fever" (1830), catalysed the reforms of the British health system,[29] but these did not promptly affect the Australian administrations.[3] In the colony, proper hygienic practices -including waste management-, only started in the late years of the 19th century.[2][3] This shift was partly due to the change in the administration nature of the colonies, which prior to that moment had limited the participation of the public in their affairs.[3] Eventually, a more democratic and representative system was put into effect.[3] The waste classification system prior to federation in 1901[30] was not formalised and most refuse was directed to landfills or left in the streets.[3][31] Exceptions were due to waste sea burials and to limited incineration practices, and required sorting in two additional streams characterised by flammable or sinkable waste.[3] Recycling rates reduced,[2][3] with only the low income classes inclined in pursuing these practices.[2] Melbourne was considered the world's dirtiest city in the 19th century.[3] Its water and waste management systems were not able to keep up with the booming in population that followed the gold fever,[31][32] hence the nickname "Smellbourne".[32] Its hygienic conditions were described as "fearful" in 1847 by the council's Sanitary Committee,[22] which also stated the necessity of building new infrastructures to lessen epidemic risks.[22] Infections and diseases rates were high, compared to those from other world cities like London.[31] Typhoid and diphtheria were not rare and by the 1870s the city serious hygienic issues, reaching high infant mortality rates.[31] The Royal commission proposed to design a board of works in 1888, which was eventually established in 1890 under the name of Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW).[31][32] The scheme that would have reformed the usage (at that time comprehensive of both freshwater supply and sewerage disposal) of Melbourne's Yarra River waters was launched during the depression which hit the city during the 1890s.[32] The initial debt and difficulties did not stop its creation, and the building processes started in 1892.[32] By the end of the century, most sewage in Australia flowed underground and sewerage systems were integrated in the urban complexes.[3] Professions like rat-catcher and scavenger were fully established and supported recycling and a minimum control over the diffusion of rats.[3] 1900–1960 The councils' political asset renovation of the 19th century contributed only in part to the development of a systematic legislation.[3] The major changes in waste management were driven by the widespread of diseases and epidemics,[3][31] especially that of the Bubonic plague[2] which affected Sydney at the beginning of the 20th century.[34][35] The newly gained awareness towards public health allowed urban reorganisation and advances in sanitary standards.[3] In 1901 Australia gained the independence from the United Kingdom.[30] The lack of a centralised power which the states were exposed to limited the influence that the federation exerted on them.[3] The executive role was exercised locally, by the councils.[3] Landfills were the primary disposal sites.[3] Incinerators were starting to be adopted as a result of the additional commercial value promoted by technological implementations.[3] Their expensive nature previously led the Sydney council to decline the installation of one of such a plant, in 1889, but the plague which later spread in the area had the effect to reform priorities and justify the expenses.[3] The first decade of the century saw a rising demand of incinerators.[2][3] A second accretion in the sector had place in the 1920s[2] and it was largely due to the production of an Australian model,[3] the Reverberatory Refuse Incinerator.[36][37] In the same decade, the recycling of paper started in Melbourne.[2] WWII, technological advances and the clean air debate from overseas eventually imposed back landfill disposal over waste burning.[3][38] During the Second World War the resources demand necessitated a strong recycling strategy, but by the end of the conflict priorities changed and recycling was discarded in favour of landfill disposal.[2] Landfills also benefited from the technological advances acquired from the United States, and more sophisticated plants were built.[2] Hazardous and industrial waste were not known, or either ignored threats, and all wastes formed a general, unique stream that would have eventually ended up in landfill.[3] Since the Fifties the industrial refuses received different attention and their disposal requirements improved.[2] Leachate, the contaminated liquid which percolates through landfill material, was not prevented and this resulted in cases of environmental damages.[2] 1960–1990The population growth factor in 1871 was 27% in Sydney, 26% in Melbourne and 23% in Adelaide.[39][40] They reached 56%, 65% and 79% respectively in 1961.[39][40] The New South Wales capital counted more than 2,000,000 residents; Melbourne was close, having 1,911,000 inhabitants, and Adelaide 587,000.[39][40] The increase in population boosted land reclamation, and landfill siting began to be more challenging.[2] Chemical and hazardous traits of waste began to be internalised in the disposal method evaluations since the Sixties,[2][3] along with an augmented influence and regularisation by the Commonwealth.[3] Standard landfills started not to accept certain types of waste, but these measures did not take into account the escalation of illegal practices which arose as a response (such as clandestine dumping).[2][3] The paper and newspaper recycling sector reached a 30% recycling rate.[2] Deposit refunds for drink containers were shut down a decade later, in the 1970s, following the implementation of the recycling industry for bottles.[2] Public interest towards recycling and environmental protection arose greatly,[2][41] yet the process of collecting recyclables was finite to specific geographic areas.[41] The Canterbury Council was the first in differentiating the waste sorting into recyclables and household waste, in 1975.[2] Efforts were made especially for reducing visual pollution and, with it, litter.[2] Clean Up Australia Day was first held in January 1989.[42] More people started to recognise the issues related to litter and to the waste management practices, and the government evaluated the return of the deposit refund and the taxation of non-recyclable products.[2] These were ultimately not implemented, except for South Australia.[2] 1990–2000The inappropriateness of the waste management strategies started to be evident in the last decade of the 20th century, with the cities undergoing a process of rapid population growth and the states being unable to contrast unregulated landfills.[2] Landfill was still the preferred disposal method, although incinerators and recycling proposal began to be pondered again as alternatives.[2] Paper and glass differentiated collection were not rare.[2] The adoption of waste levies, recyclables sales and the agreements with various industry sectors allowed the creation of new means of introit.[2] The main constraints were represented by the residents, with the majority not sensitised in the matter.[2] 2000–presentThe federal government gives ample autonomy to the single states, resulting in a miscellanea of laws, independent projects and objectives produced by each state still characterising the current waste management system.[2] However, the Commonwealth has increasingly issued frameworks and policies with the aim of rendering the national waste management more consistent.[2][4]  Australia is currently considered to be one of the greatest consumers of carbon and resources within the countries that relate to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.[43] More advances, including in waste management, are needed to comply with the Paris emissions goals.[43][44][45] The national waste management framework is under implementation to establish a more consistent and circular-economy-based legislation,[6] a more reliable database[7] and a stronger, more independent domestic industry.[6] The waste management industry is currently worth about AUD$12.6 billion and contributes to the national economy with AUD$6.9 billion per annum.[6] Classification of wasteThe final objective of classifying waste is that of preserving the healthiness of both humans and environment by appropriately defining its properties.[3][46] Different classifications had been produced by multiple sources over the years, leading ultimately to a diverse range of systems and definitions.[46][47][48] Each state had implemented its own systems with specific terminologies.[46][47][48][49][50] In the case of surveys and reports being provided by industries and businesses, additional classifications can apply.[47] The same materials might be treated differently, in respect of the regulatory structures that categorise them as "waste" or "resource".[46][48] The National Waste Classification System was developed as a sub-project of the Australian Waste Database (AWD, 1990), but it was not widely implemented.[5][46][48] Its benefits -for policymakers, local manufacturers and communities-, had been highlighted by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO),[51] and yet a 2011 study disclosed that only Tasmania and the Northern Territory were fully aligned with it, and only two states, namely NSW and WA, partly did so.[48] In that occasion the Department of the Environment and Energy also expressed its commitment to submit a definitive, harmonised system.[48] Advances towards a system standardisation are recent and correlated to legislative modifications occurred in the last fifteen years.[52] One of the definitions provided for "waste" has been that of the Victorian "Environment Protection Act 1970", which described it as "any matter, whether solid, liquid, gaseous or radioactive, which is discharged, emitted or deposited in the environment in such volume, constituency or manner as to cause an alteration of the environment".[53] The 2018 National Waste Report defined waste as "materials or products that are unwanted or have been discarded, rejected or abandoned."[5] That classification included recyclables and waste-to-energy materials within the waste category, and excluded those that were not subjected to reprocessing prior to being reused.[5] In general, three waste streams are identified in Australia:[46][48][50]

Kerbside and hard waste collection are usually considered within the first category. Soft plastics, paper and organics are its key components.[50][54] Timber, plastic and metals characterise the second category. They are considered to represent an optimal and valuable source of recycling materials.[50][54] C&D waste products are usually inert, such as concrete, steel and earth that has been excavated.[50][54] DatabasesAustralian waste management had to comply over the years with a general scarcity of data from both businesses and institutions.[5][51][54][55] Statistical analyses, when provided, had been of varying usefulness to the governmental organs.[54][55] Main issues have been attributed to the lack of consistency, methodology, field-related expertise and legislation effectiveness.[7][52][56] In particular, the different systems, classifications and technical terminologies adopted by each jurisdiction, and required by the diverse stakeholders range and nature,[57] increase the complexity in both the data collection and wrangling processes.[5][48][50] Even where similarities are present, data can overlap.[46] An inquiry made by a governmental office in 2006 reported the waste management sector data to be inconsistent, incomplete and subjected to biases.[47] The data level of confidence had underpinned the ability of producing resonant policies, and in particular those regarding a sustainable management of resources.[46][51][56] There had been attempts to create an harmonised system, however the success of such projects had been hampered by the management costs associated with reforming the legislation already in use.[5][47] The first, not successful ones were made in the 1990s for reviewing the achievements of the 1992 "National waste minimisation and recycling strategy".[7] The quality eventually improved in the following decade, but the different standards among the years also meant that trends could not be understood by just referencing to the various reports commissioned at that time.[7] A more consistent data system started to be implemented after the release of the 2009 "National waste policy".[7] It was developed and ratified by all the states in 2015 and currently six of its annual versions represent the national waste database.[7] Validation and testing methodology are implemented by some researches to reduce biases and minimise errors occurrence.[58] Current management systemPrinciplesThe framework onto which the legislation is currently working is what has been named "The 3Rs plus 1": reduce, reuse, recycle and recover energy.[54] The approach is intended to be directed towards the circular economy principles.[54][59] The system has received critics from researchers (who are not convinced of the actual circularity of the proposed economy),[60][61] as well as from institutions that urge the concrete application of the principles thereof.[59] The main reason leading the critics is that a true circular economy should prefer the avoidance of waste over its reuse and recycle (in alignment with the waste hierarchy principles),[62] while no clear actions have been made towards the former goal.[60][61] Waste hierarchy The waste hierarchy describes the priorities linked to the waste management via a preferential order, on the basis of the efficiency of each of its strategies towards the production, use and disposal of a product.[62] It is often represented as an inverse pyramid, grading from the top "most preferable" to the bottom "least preferable" solutions.[62] The waste hierarchy sets efficiency as an aim, and over-consumption as an avoidable, unnecessary occurrence that can be diverted by appropriate changes in the consumer behaviour.[62] The disposal of waste serves, theoretically, as the worst-case scenario; in practice, the usage of landfills is widely adopted.[54] This happens because the hierarchy is not suitable in every circumstances: the evaluation of costs-benefits needs to be implemented in its consultation.[54][63] Its application as a guide for national policies has been widely spread since the last decade of the 20th century, and it is central to the "National Waste Minimization and Recycling Strategy".[54] The various waste hierarchies implemented by each jurisdiction, although almost identical in functions and structures, have been enshrined in different acts, and at different times. Queensland describes it in the "Waste Reduction and Recycling Act 2011";[64] in Victoria is part of the foundations of the "Environment Protection Act 1970";[53] in NSW is mirrored by the "Waste Avoidance and Recovery Act 2001".[65] Policies and regulationsFederal waste-related legislation is under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Environment and Energy.[4][66] (1992) National Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable DevelopmentThe strategy was endorsed in 1992 and represented an action towards the Ecologically Sustainable Development (ESD).[67] ESD was defined in 1990 by the Commonwealth Government as "using, conserving and enhancing the community's resources so that ecological processes, on which life depends, are maintained, and the total quality of life, now and in the future, can be increased"[68] and the same definition had been used in the strategy.[67] The National Waste Minimization and Management Strategy developed as a corollary.[67] National Waste Minimization and Management StrategyThe strategy was developed under the "National Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable Development" to serve as a framework with which improvements and effective measures could be coordinated.[67] In particular, it focused on hazardous waste and waste disposal.[67] (2017) National Food Waste Strategy. Halving Australia's Food Waste by 2030The document represents a guidance for Australian institutions, outlining the actions needed to be pursued to reduce food waste by 2030.[69] It is inspired by the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal 12: "Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns",[70][71] and by the Country's commitment towards the reduction of gas emissions (heavily produced by organic compounds in landfills).[69][72] The latter aligns with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.[69] (2009, 2018) National Waste Policy: Less Waste, More ResourcesThe 2018 text succeed the National Waste Policy of 2009,[6][73] and it represents the foundations on which governments and individual jurisdictions can relate in their legislative activities, while also stating their responsibilities.[74] The policy encompasses the MSW, C&I and C&D streams, considering liquid, gaseous and solid waste and excluding radioactive materials.[6] A total of sixteen waste strategies are exposed.[74] It will be in use until 2030 and, while setting the guidelines for governments, specific local and regional circumstances considerations for businesses and communities can still be pondered and implemented[6] The document presents itself as with a circular economy footprint.[6] Waste avoidance and recycling implementation are two of the five principles on which it is based.[6] (2011) Product Stewardship Act 2011Product stewardship refers to the regulations that set a product management strategy which ensure that each sector involved in the lifecycle of a product (including production and disposal), shares a responsibility towards its environmental and human impacts.[75] In Australia its regulation on a national basis has started in 2011 with the "Product Stewardship Act".[76] The act states the voluntary, co-regulatory and mandatory product stewardship and it implements the guidelines with which products must be thought of in terms of environment, health and safety.[77][78] The Department of the Environment and Energy annually publishes lists in which new regulated products are considered and included.[78] The first scheme developed under the act was "The National Television and Computer Recycling Scheme", in which both governments and industries were considered responsible of the management of electronic media products.[74][79] The last products introduced in its regulations include batteries, plastic microbeads and photovoltaic systems.[76] (2018) Threat Abatement Plan for the impacts of marine debrisMarine debris were considered and listed as a major threat to wildlife in "Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act" (EPBC) in 2003.[80] Plastic is a prominent source of such debris and it was on this basis that the plan was established.[81] In particular, it focuses on the actions needed in the research and in the understanding of the impacts of plastic and microplastics on marine environments, and on the actions needed to minimise their effects.[81] State regulationsIn various states, including Queensland, Victoria and Northern Territory, waste management is considered a general environmental duty and breaching this duty could result in penalties.[82] Waste duties include:

Waste levyThe waste levy is a taxation imposed on the amount of waste disposed in landfills.[85] Waste levies can determine the preferential approaches of the industry over waste function by encouraging alternative or traditional disposal and recovery technologies.[85][86] In terms of environmental impacts, an efficient usage of the contribution should incorporate their costs and benefits into the management of values thresholds.[86] Queensland used to have a waste levy, but in 2013 the Newman government repealed it.[87] The levy was considered at that time not effective both economically and environmentally, as it would have unnecessarily increased managing costs to businesses and promoted illegal dumping.[87] Other states, in the meantime, taxed landfill usage.[88][89] In NSW, for example, the levy was introduced in the "Protection of the Environment Operations (Waste) Regulation 2014" and in 2018–2019 the standard levy in the metropolitan area reached $141.20 per tonne ($81.30 per tonne in the regional area).[90][91] Queensland is planning to reintroduce the levy on 1 July 2019 in most of its local government areas.[92] It is projected that by the end of the first four years from the commencement of the levy, 70% of the incomes perceived will be redirected to councils, startups and other projects.[92] ProductionDiverse factors are involved in the production of waste, namely economy, demography and geography.[54][93] Australia produces much waste;[94] according to various studies, this is due to an economy based on an intensive use of materials,[54] to population growth (as of September 2018, Australia counts more than 25 million people),[93][95] population demographic and urban sprawl, and Gross domestic product GDP.[54][93] In 2018, Australian GDP grew by 2.3%, and every year in Australia about 67 million tonnes of wasted are generated (~2.7tn per person).[6] Municipal solid waste and commercial and industrial streams reduced their growth rates, while those of C&D increased in 2019.[50] The strategies adopted by lower chain links, as retailers, have also a role in the production or minimisation of waste.[2][43][96] The general disbelief towards the positive effects of reusing and recycling have impacted the amounts generated.[2][43] About 20% of the total waste generation is due to coal in forms of ash and fly ash.[50] Except for the Northern Territory and for Western Australia, 77% (or 150.9 TWh, terawatt per hour), of the total electricity provided by the National Electricity Market (NEM) in 2016–2017 was sourced from coal.[97] Littering Littering is a major issue in Australia, with $180 million per year spent in NSW only.[98] A decrease in its occurrence has been registered, although Victoria and Western Australia have recorded an inverse trend.[99] The former records 14,560 tonnes of litter generated per year, 75% of which is constituted of cigarette butts and packaging;[99][100] in NSW the number increases up to 25,000.[98] In Australia members of the public can report littering practices to the local Environment Protection Authority (EPA) agencies, as declared by documents such as the Local Nuisance and Litter Control Act 2016 (SA).[100] In Victoria, 20,000 reports are generated annually.[100] Single use plasticsAccording to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), 95% of the plastic packaging is discarded after a single use.[101] In March 2019 the organisation published "Solving Plastic pollution through accountability", a report issued on an international basis and which urged governments to stop accepting projects contemplating the use of virgin materials.[102] Additionally, it supported a global ban to single use plastics and requested the producers to be considered responsible for how their products are ultimately disposed of, and recycled.[103] The single use plastics have been already banned in Europe.[104][105] In the same month of the WWF publication, Hobart the first capital in Australia to ban single-use plastics,[106] although not without criticisms by the local businesses.[107] The Tasmanian Small Business Council demanded a coordinated action between government and local businesses, that could have otherwise been damaged by a sudden and costly ban.[107] Other states are pondering the ban, such as SA[108] and ACT,[109] while in the meantime there are several cases of bans on plastic bags, like those in Queensland,[110] Western Australia,[111] Victoria[112] and Darwin.[113] South Australia banned them in 2009 already.[114] Companies and institutions, such as McDonald's, Starbucks and the Sydney Opera House, are banning the use of straws.[115] In July 2018, Coles banned plastic bags from its retail shops.[96] The decision was followed by a consistent flux of critics from its shoppers and indecisions by the company.[116] In NSW the decision of Coles and Woolworths to stop supplying single-use plastic bags set off many controversies.[117] NSW is also the only state that has not yet formally took action against the use of single-use plastics, in what has been named the "ban on bans".[118][119] Advances in the reduction of single-use plastics are progressing on a nationwide view.[115] The number of reusable cups sold and responsible cafes registered have fluctuated in 2018.[115] Councils are repeatedly been asked questions by residents regarding the disposal of recycling, showing an increased interest in the subject matter.[115] CollectionCollection services vary in terms of types provided and areas in which they are implemented[5] The National Waste Report 2018, which is built upon data as of 2016–2017, reported that some services can be absent in certain locations (Table 1).[5] In the same years, kerbside collection was available in 90% of the households from all the states, with the exception of the Northern Territory.[5] The organics collection represented the less developed one with only 42% of the households having access to it -less than half the figure for both recycling and garbage collections.[5] A research conducted by Pollinate and Planet Ark in 2018 reported that the most requested recycling services by the households regarded, in order of prominence, organics, soft plastics and e-waste.[115]

SAP: service always, or nearly always provided; SUP: service usually provided; SRP service rarely, or sometimes provided.[5] LabellingUncoordinated labelling has impacted the sorting processes antecedent the waste collection dynamics,[50][120][121][122] which have been also influenced by the households' generally low education on labelling systems[50] and on contamination of recyclables.[122] A harmonised action has been taken by Planet Ark, PREP Design and the Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation, producing the Australasian Recycling Label (ARL) as a result.[120][123] The label refers to each component of a package (for example, of both a bottle and its cap), and it states its end-of-use destination.[120] The destination is distinguished in three categories: recyclables, not recyclables and conditionally recyclables.[120] Conditionally recyclable products can be potentially recycled, but they might undergo further restrictions depending on the state or council.[120] Examples of their destination can be either the red or yellow bins, or the store drop offs.[120] The system has been already implemented in the major market streams and some of its supporters include Nestlé, Unilever and Woolworths.[120] Waste bins The requirements for colours, markings and designations are specified in AS 4123.7-2006 (R2017).[125] The standards were first set in 2006 and they have been reconfirmed in 2017. The standards are also in use in New Zealand with most councils allowing the following in each waste bin:[125]

A 2018 report by Blue Environment estimated the average composition (by weight) of yellow-lid bins to mostly consist of paper (56%), followed by glass (25%), and then plastics, metals and other materials all in single figures.[126] The adoption of a unique bin for a wide range of recyclables may cause contamination problems,[127] but it has the side-effect of diminishing the number of trucks (and consequently air pollution), required for the collection processes.[50] The contamination of the materials collected causes the diversion of recyclables to landfills.[54][127] Most of the kerbside collected waste in 2016–2017 was disposed of in landfills.[5] Container deposit schemesSouth Australia has introduced container deposit schemes (CDS) since 1977; Northern Territory established them in 2012.[5] They were the only two operative schemes in 2016–2017.[5] SA had a return rate in that period that almost doubled that of the NT, reaching 80% with 587 million containers sold.[5] New South Wales introduced its scheme in 2017[128] and was quickly followed by Australian Capital Territory[129] and Queensland[130] in 2018, Western Australia in 2020,[131] and Victoria late 2023.[132] Collected containers have been treated both domestically and overseas.[5] TransportThe collection of solid and recyclables materials from households, industries and other places usually leads to the transport towards Materials recovery facility (MRF), transfer stations or landfill sites.[54] Materials recovery facilities (MRFs)Materials recovery facilities, or materials reclamation facilities, or multi re-use facilities, receive the commingled materials from the collection trucks.[133] They have the function of sorting and aggregate recyclables.[133] MRFs are generally similar in structure and require both manual and automatic procedures (see video in this section). The former are especially useful when the materials received are particularly contaminated and/or do not respect the requirements for being sorted.[133] However, the majority of MRFs in the country have deficiencies in sorting co-mingled MSW, leading to a rise in the levels of contamination.[127] Recovery and reuseWaste reuse identifies those dynamics that lead to the reuse of materials that have been included at some stage into the waste management processes.[5] Waste reuse has more positive effects on the economy than recycling for two reasons: firstly, the former has the potential to employ more people, and secondly, the value of reused waste materials is higher than that of recyclables.[5] Australia annually recovers about 2 million tonnes by waste-to-energy approaches.[5] Of all the Australian jurisdictions, Queensland is one of those with the worst recovery rates.[134] It also appears to have low standards on an international basis.[134] In the years spanning from 2007 to 2016, the state performances in the sector did almost not change at all.[134] The estimates made by the Queensland's Department of Environment and Science revealed a recovery rate of less than 45% in the financial year 2016–2017.[134] They represent a huge gap from those of the current leader, South Australia,[134] which in the same year diverted from landfill more than 80% of its generated waste.[134][135] The figures for SA show that the geographical origin of waste, as well as its typology, strongly affect the diversion percentages.[135] For example, C&D recorded an 89% recovery rate in the metropolitan area, and of 65% in the regional.[135] However the commercial and industrial category performed better in regional SA (93%), rather than in the surroundings of Adelaide (82%). Municipal solid waste (MSW) diversion scored the lower percentages, reaching only 39% in the regional area.[135] The national recovered waste average floats around 58%[5] to 61%.[134] Queensland would need to divert almost 40% more than its current performance to reach it.[134] Recycling The aim of recycling is that of producing new materials from old unused ones, without using raw materials.[54] The recycling industry in Australia is crucial in the realisation of the National Waste Policy: Less waste, more resources objectives.[137] It involves multiple sectors of waste management, and requires specific collection and sorting practices which precede the sale of recyclables.[54] The industry has many points to improve, with low recycling rates, confusing rules, and lower rates compared to more developed countries.[5] Despite these problems, Australia has begun investing more in recycling and waste management with new laws, grants, policies, and strategies to assist in these improvements.[138] It has been estimated that in the financial year 2009–10, the recycling sector was worth $4.5 billion (AUD), with an additional $5 billion if the entire waste management industry is considered.[139] In South Australia, which is currently the leader in the sector,[134][135] resource recovery activities employ almost 5000 people and contribute more than half a billion Australian dollars to the SA Gross State Product (GSP).[140] TreatmentThermal technologiesIncinerators, pyrolysis and gasification are some of the thermal treatments into which waste can be diverted.[54] They might be accompanied by energy recover.[54] In Australia, the waste-to-energy approach is becoming by the time more favoured by both councils and industries.[141] The major environmental pros of these practices consist of the decreasing adoption of fossil fuels, whose use compared to that of waste fuels may potentially produce more carbon dioxyde.[142] IncineratorIncinerators plants had sensibly developed over the years and now advanced pollution control devices enhance their environmental standards.[54] The most up-to-date waste-to-energy plants ameliorate their ecological performances by capturing CO2 emissions produced by the combustion of fuels;[142] carbon dioxide can also be then diverted and used by other processes.[142] Pyrolysis and gasifications are some of the waste-to-energy approaches.[86] These require the heating of waste in anaerobic conditions (without oxygen), to produce a fuel, the pyrolysis oil.[86] The oil can subsequently be gasified to produce the syngas.[86] Technologies to manage the emissions from these plants exist, but Australians are sceptic and concerned about them.[142] There are also critics relating to the idea that waste used as fuel could weaken the recycling industry.[54] They are supported by the fact that Australia has a little domestic demand in the sector of recyclables.[59][143] However, incinerators could be a tool for diverging contaminated materials from landfills in a way that promotes the waste hierarchy principles.[142] Living in the proximity of an energy-from-waste facility can lead to epigenetic modifications associated to heavy metals.[144] Heavy metals have been reported to occur within a certain radius from the incinerators.[145][146] Other toxic pollutants, including dioxins, have been documented to be produced by the combustion processes.[147] Landfills generate methane, a greenhouse gas naturally produced, but it is still discussed whether its emissions might be better than those of incinerators.[50][142] The preference of incinerators over landfills might be advantageous in social and political terms.[50] While the latter has an end-of-life (filling) and requires the jurisdictions to find new sites, the former, although sharing the characteristic of not being wanted by the nearby households,[147] does not need to move over time and will mainly affect only a relatively small area.[50] Queensland and Victoria tends to incinerate more than other states.[50] Western Australia started a project in 2018,[148] while in NSW, in the same year, the construction of a waste-to-energy plant in western Sydney was refused.[149][150] DisposalLandfill Australia depends on landfill disposal.[50] It represents a cheaper solution than others and this might have slowed down the advances in the recycling industry.[50] Landfill siting must consider multiple factors such as topography, local natural habitats and distances from the urban centres.[54] Most of the landfills are found in the metropolitan area of the states' capitals, with a major concentration in the southwest and southeast of Australia.[58][151] It results in a highly clustered overview,[58][151] with three-quarters of the total amount of waste produced collected in only 38 sites.[38] The number of landfills has decreased in the last 30 years, but they have become bigger and more sophisticated.[38] NSW has the largest disposal plant in Australia.[38] Landfills are planned to manage the flow of leachate and gas produced by the waste.[54] Products such as PVC, which contains phthalates, and timber, that can contain chromated copper arsenate (CCA) if it has been treated, can potentially release these components into leachate.[54] Methane, a gas with a greenhouse effect potential at least 25 times more stronger than that of carbon dioxide (CO2),[142][152] is emitted by biodegradable carbon sources materials within the landfill.[54] Most advanced plants reuse methane emissions by combusting it in a waste-to-energy approach.[38] A preferable solution -when considering waste hierarchy and climate change-, is that of adopting composting and special bacteria for limiting the amount of emissions produced.[38] National relationsStates and territoriesThe last year in which Queensland imposed a landfill taxation was 2012.[89][134] The emerging discrepancy between the levy legislation in Queensland and New South Wales supported the introduction of waste from interstate within the QLD borders,[134] with the additional effects of pollution originated by transports.[50] These dynamics and the dominant role of the levy were confirmed in 2017 by the Supreme Court Judge who was in charge of an investigation commissioned by the Queensland offices.[153] According to the investigation, the policy framework adopted by Queensland would have unlikely allowed a decrease in the quantity of waste from interstate.[153] The prospect led to the recommendation of the re-introduction of the waste levy, and it was backed up by a positive response by the government.[134] The levy is now expected to begin on 1 July 2019, and it will concern 39 out of 77 local government areas.[92] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communitiesWithin indigenous communities it can be more difficult to manage waste.[154] This is particularly true where these communities live in remote areas,[154] in which even machinery may be scarce.[155] Transports, collection, associated costs and the indigenous way of thinking towards garbage are some of the main aspects that have been pondered.[154] The NSW "Aboriginal Communities Waste Management Program" and "Aboriginal Land Clean Up and Prevention Program" are some of the programs addressed to the Aboriginal communities.[156][157] International relationsUnited Nations

The UNEP program was established in 1972 and it is recognised on an international basis.[158][159] It coordinates the UN's environmental projects and supports environmental-focused strategies in developing countries.[158]

The global, non-binding action plan was a product of the Earth Summit, a United Nations (UN) conference on environment and development held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, from 3 to 14 June 1992.[160][161] The main purpose of the conference was that to persuade the governments to include environmental concerns within their economic development strategies.[160][161] The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC Act 1999), still in force,[162] was the Australian response to the Agenda 21 commitments.[163]

The Basel Convention under the UNEP was ratified by Australia in 1992.[54] Mainly focusing on international markets, in particular the international exports from richer to poorer countries, it had as main objective the control and regulation of hazardous waste disposal.[54][164] As a legally binding agreement, it was supported in Australia by the Hazardous Waste Act, for which is considered as an offence the unregulated export of hazardous waste.[165] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)Under the OECD[166] Australia has submitted in 2019 its third Environmental Performance Review related to the years 2017–2019.[43][167] Strategies specifically linked to the Australian case on a national perspective are to be discussed between the organisation Environment Policy Committee members.[167] China and Asian marketsAustralia used to rely on Asian markets, especially on China, for waste treatment and disposal.[59][126][168] Since the Chinese "National Sword" policy came into effect in 2018, the waste management industry entered a crisis:[6][60][122][169][170] of the 1,248,000 tonnes (30% of the total produced per annum) of recyclable materials sent to China only in 2016–2017, 99% had been affected.[126][169][171] As an interim solution, exports have since shifted to, and enlarged, alternative markets, such as those in Vietnam and Indonesia.[5][140][143] An increasing number of Asian Countries is also planning to limit import rates,[172][173][174][175] increasing the urgency of a shift towards the circular economy and a reliable domestic industry.[5][122] The domestic policies in Australia did not include any clause in sharing risks associated with commodity prices with the recycling industries.[5] The Chinese import restrictions led a fall in these prices and forced many to stockpile their materials while waiting for new market opportunities.[5] Human behaviourWaste management practices, especially avoidance and recovery related to household materials, have been linked to consumer comportment.[168][176] Illegal practices as littering and dumping are also connected to it.[177] Targeted education and awareness campaigns are likely to affect these practices and, consequently, the effectiveness of the management outcomes.[121][177] Media coverage and government campaigns have positively affected the public eye towards the recycling issues.[178] Topics as single use plastics and packaging have received particular attention in the last decade.[178] Recycling practices and recyclables production particularly depend on consumer awareness for future implementations.[121] Industries, as well as communities, will be subjected to campaigns and their effectiveness is considered a challenge for local and state organisations.[179] Many cases of product-consumer dynamics are actually perceived as unsustainable by both residents and organisations,[180] but Australians are seen expecting government and industry inputs to firstly react to them.[50][180] More than 85% of residents, the Australian Council of Recycling (ACOR) stated, agree with recycling practices.[5] Where these non-spontaneous initiatives are offered for free, as some which developed in South Australia, the feedback has been recorded as particularly positive.[179] Items such as photovoltaic cells and e-waste, however, are not feasible to dispose and usually require private expenses by the owners.[179] In this case, the eco-prompt inspiring their discard is less apparent.[179] Campaigns and actionsLitter and illegal dumpingLitter report is a strategic mean used nation-widely as a supplement to EPA in its investigations; it has been implemented in all the states: NSW,[98] QLD,[181] VIC,[182] TAS,[183] WA,[184] SA,[185] ACT[186] and NT.[187] In 2015, NSW launched RIDonline, an online platform (as of 2019, still accessible), where the public can report illegal dumping practices.[188][189] One of its objectives is to help the state picturing an evidence base from which construct future management strategies.[188] (2017) EPA statewide "tosser" blitzResearches have shown that only about a quarter of the NSW residents actually think they can be caught for littering, and that those who realise measures can be taken against them for littering are not that numerous.[98] During Easter time in 2017, EPA worked with other agencies, councils and companies such as McDonald's, on a statewide campaign against driver tossers[clarification needed].[98] The aim of the project was to remind people that fines and measures can be directed for littering in any place and time.[98] Sensitization campaigns(1980s) Do the right thingThe campaign aimed to sensitise and educate households about themes such as littering.[2] The main media used was television, and it has been considered a successful campaign.[2] (1996–present) National Recycling WeekStarted in November 1996 by PlanetArk, the National Recycling Week consists of an annual media campaign, still in action, with educative roles as objective.[41] It aims to sensitise the public eye on themes such as recycling and responsible resource managing.[41] The next event National Recycling Week will take place in November 2019.[190] Projects for people in need Researches show that currently, in the world, there is enough to feed everyone, with about 3 billion people suffer from hunger or malnutrition.[191][192] In Australia only, figures reach 3.6 millions.[193] Projects against food wasting had developed throughout the country, with the aim to feed people in need via edible products that would have been otherwise discarded.[194] Waste levy waiver for disaster wasteOn the 13th of February 2024, high temperatures, strong winds and lightning strikes caused a power outage in Victoria which resulted in a blackout for more than 620,000 homes and business across the state. About 12,000 km of power lines were impacted.[195][196] Following the power outage, the Victorian government implemented a waste levy to dispose of disaster waste deposited or damaged on the 13th of February.[197] The free waste disposal is available to residents with proof of identity and proof of residence in a local government area impacted by the bushfires and storm on the day of disaster until the 30 April 2024.[198] Reports and surveys(2000) Report of the alternative Waste Management Technologies and Practices InquiryThe report was produced by the Alternative Waste Management Technologies and Practices Inquiry for the NSW government in 2000.[86] Its purpose was to provide an informative background for the future waste management and technology implementations in the state.[86] The framework onto which it was based on supported ecologically sustainable development and focused on technology, economy, society and environment.[86] The document started by questioning:

and structured the report on the investigation of them.[86] It provided the illustration of the "triple manifesto", defined as the close relation shared by the State or regional technologies, practices and strategies in the context of waste management.[86] The manifesto led to state the necessity of considering the different benefits that can derive from the usage of waste as a resource, before opting for less productive solutions as landfills.[3][86] On these premises, the Inquiry suggested a reform in the NSW strategies which were then based on the disposal of waste as a preferential approach.[86] (2009) Love Food Hate WasteThe NSW government started the Love Food Hate Waste program in 2009 and conducted a series of tracking surveys until 2017, having food waste as the key interest.[180] Covered topics ranged from meal planning and waste value to government role expectations and media influences.[50][180] In 2017 the survey was conducted online and 1389 residents participated to it.[50] The outcomes suggested that Love Food Hate Waste campaigns and the media contents had positively impacted certain population sectors.[50] It also showed how environmental concerns are seldom related to food waste.[50] More people had started to realise that they could throw away much less organics, but advances in this direction recorded in the previous study in 2015 had declined and in NSW more food was being wasted.[50] Only 61% of the residents practised five or more waste avoidance behaviours, and packaging was still considered as the primary source of waste.[50] The 2017 study differed from the others since it added another question to the survey, related to the perception of avoidability pertinent to food wasting.[50] Up to 27% of NSW residents were shown to not consider peels and bones as waste,[50] while younger respondents considered items such as unfinished drinks as "unavoidable".[180] Expired products and unfinished meals were the most popular reasons for wasting food, and meal planning recorded a decrease since the previous survey.[180] Older segments of the sample reported to consider portion size more often than the younger.[180] $1645.64 (AUD) was the weighted average answer when people were asked to estimate the annual waste costs produced. However, EPA had estimated at least $1260(AUD) more.[180] 68% of the respondents, and 82% of those from an Asian background, supported the idea that the government should implement the reduction strategies in this waste category.[180] (2010–present) National Waste ReportThe National Waste Report is a series of documents endorsed by the Australian Government. It started in 2010 and as of 2019 four reports have been produced: in 2010, by the Environment Protection and Heritage Council (EPHC);[199] in 2013;[200] in 2016, by Blue Environment Pty Ltd for the Department of the Environment and Energy;[171] and 2018.[5][201] Their studies span one financial year each and provide statistics and commentary on several aspects of waste management by using different key focuses (for example, on a per capita basis).[5] From 2016 onwards, the reports have been supported by the National Waste Data System (NWDS) and the National Waste Database.[5][202] (2017–2018) National report 2017-2018: National Litter IndexThe National Litter Index of 2017–2018 was the twelfth survey conducted by Keep Australia Beautiful.[99] Rather than answer to "why", its descriptive objectives regarded the "where" and the "hows" of littering nationwide.[99] The index revealed that the counted amount of litter decreased of 10.3% in comparison to the previous year data, although in VIC and WA it had actually increased.[99] The takeaway packaging was the category which differentiated the most, with a decrease of almost 17%. The major reductions were observed in NT (34%), and less of half that figure was recorded in NSW and SA.[99] In terms of sites, beach littering and shopping areas registered the biggest and smaller decrease respectively (22.5%, 12.9%).[99] Thirty-eight litter items per one squared kilometre was the average estimated on a national basis, with retail strip malls as density hotspots.[99] (2018) Planet Ark National Recycling Week: From Waste War to Recycling RebootThe survey was conducted in parallel by Pollinate and Planet Ark.[172] It illustrated the recycling activities and perceptions of Australians, as well as undercover anecdotes and propose potential alternatives such as the circular economy.[172] (2019) Waste away: a deep dive into Australia's waste management"Waste away: a deep dive into Australia's waste management" was a podcast episode launched on 20 February 2019.[50] According to its participants, in NSW 72% of the people who have been surveyed would recycle more if a more reliable recycling system was offered.[50] It revealed that in Victoria the knowledge about household waste collection was generally good, but such a result was not evident on landfill and recycling topics.[50] It also showed that waste was generally accepted as an essential service, although the household responsibility was lower in the public eye compared to those of businesses, companies and government.[50] Issues(1974–1998) Castlereagh Regional Liquid Waste Disposal DepotIn 1974, in Londonderry, Castlereagh, western Sydney, what was supposed to be a temporary plant was built.[2][3] It was the response from the local government to an issue relating to the disposal of liquid waste in the metropolitan area of Sydney,[2][3] which was worsening as a result of the clandestine activities and of the shut down of the previous plant in Alexandria, Sydney.[3] The disposal depot was originally scheduled to operate for a maximum of two years, exclusively disposing of non-toxic waste.[2][3] De facto, operations protracted for more than twenty years under a series of legislative variations and approved extensions.[3] It was only when the local residents organised themselves under the name of "Londonderry Residents Action Group for the Environment", aka R.A.G.E., in 1989, that an effective and definitive action was requested by the administrators.[3] Inspections, that were funded by the Waste Service NSW, supported by RAGE and investigated by "Total Environment Center" (TEC), concluded that within the materials being treated as dangerously non-predictable miscellany of compounds - including hazardous ones - were introduced in the normal flow of waste in the plant.[3] In addition, defaults in the system allowed liquids to escape as leachate, contaminating what had become in the meantime a residential area.[3] RAGE alleged that numerous, misleading documents and reports were given by the Metropolitan Waste Disposal Authority, NSW (MDWA) and by the Waste Management Authority (WMA), which in turn reported to the police that no dispersion had ever occurred.[3] The plant was eventually closed in 1998,[2][3] most likely as a result of political rather than environmental concerns.[3] (2000) Sydney Olympic Games preventive clean-upThe Olympic Games held in Sydney in 2000[203] succeeded a massive cleansing in the city, where unrecorded disposal sites containing hazardous waste were discovered.[2] Incidents(2017, 2018) SKM Recycling Plants In July 2017 and again in 2018, a recycling plant in Queensland, owned by SKM Recycling, took fire for several days, causing severe health, environmental and financial issues.[204][205][206] The Coolaroo plant had been receiving household recyclables from the Melbourne area, which it stockpiled as one of the consequences of China's National Sword -ultimately increasing the risks for fire hazard.[206] As a consequence, EPA blocked further waste flows in the facility in February 2019, causing the kerbside collections to be directed to landfills.[206] SKM Recycling have been legally prosecuted and charged with environmental offence in March 2019.[207] See alsoAssociations, organisations and community projects:

Environment: History:

Indexes and lists: International dynamics:

National dynamics:

Statistics: References

External links

|