|

University Club of New York

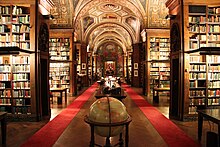

The University Club of New York (also known as University Club) is a private social club at 1 West 54th Street and Fifth Avenue in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. Founded to celebrate the union of social duty and intellectual life, the club was chartered in 1865 for the "promotion of literature and art". The club is not affiliated with any other University Club or college alumni clubs. The club is considered one of the most prestigious in New York City.[3] The University Club's predecessor, the Red Room Club, was founded in 1861 when a group of Yale College alumni founded the club to extend their collegial ties. Once the University Club received its charter, it struggled with financing, and from 1868 to 1879 the club had no permanent clubhouse and relatively few members. The club was reorganized in 1879 and became a popular social club, being housed at John Caswell's residence until 1883 and then at the Jerome Mansion until the current clubhouse was completed in 1899. Women were not permitted to become members until 1986, and are today highly represented within the membership. The current clubhouse, a nine-story granite-faced Renaissance Revival structure, was designed by Charles Follen McKim, a member of the club. It contains three main floors with a reception area at the first story, a set of library rooms on the fourth story, and a dining area on the seventh story. There are various mezzanines with bedrooms and club rooms as well, in addition to a bath and swimming pool in the basement. The clubhouse is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a New York City designated landmark. HistoryEarly yearsIn late 1861, a group of Yale College alumni from the classes of 1859 to 1861 formed the Red Room Club to continue their collegial friendship.[4][5] The club initially held meetings at the family house of Francis Edward Kernochan at 145 Second Avenue in Manhattan.[6][7] During the winters of 1862 and 1863, the club met on Saturdays in one room of the Kernochan house, dubbed the "Red Room". According to a later Harper's Weekly magazine article, the club had no regular organization; the only common trait was that the members were Yale alumni.[7] The club met at 7 West 30th Street during 1864 after Kernochan's father Joseph fell ill, interfering with the activities of the club. Cofounder Henry Holt recalled that, in late 1864, one member of the club had suggested that a university club be created.[8] Joseph Kernochan died in late 1864 and the estate was broken up, including the family's Second Avenue house.[8] Francis and his brother J. Frederic took rooms on 12th Street, where the Red Room Club continued to meet through early 1865.[7][8] Incorporation and early difficulties The University Club of the City of New York was officially incorporated on April 28, 1865, by act of the New York State Legislature.[7][9] The club was incorporated "for the purpose of the promotion of literature and art, by establishing and maintaining a library, reading-room, and gallery of art, and by such other means as shall be expedient and proper for such purpose."[10][11] The founding members had graduated from various colleges and universities in addition to Yale.[12] The club's first president, Theodore William Dwight,[a] was a Hamilton College alumnus and a professor at the Columbia College Law School.[13] George Van Nest Baldwin was the vice president, Theodore B. Bronson was treasurer, Edward Mitchell was secretary, and the founders listed in the acts of incorporation were appointed to the club's council.[14] The original constitution did not appear to have initiation fees and the club seems to have not restricted membership based on how long ago a member graduated from a college or university.[15] Nonetheless, membership was restricted to men.[3] After incorporation, the club officers wished to collect $4,500 from members to raise money for a clubhouse.[14] In November 1865, Dwight announced that all membership dues had to be paid immediately, but that less than half of members had paid their dues.[16] The next month, the club was able to sign a short-term lease at a townhouse on 9 Brevoort Place.[17] This clubhouse was on what is now 10th Street east of Broadway.[18][19] In its first year, the University Club had over 100 names on its rolls.[7][14] The club had so little money, the townhouse's landlady agreed to accept $750 of the $1,250 lease payment.[17] Disputes over financing continued through 1867, even though the space was subleased to Loyal Legion, which similarly had low finances. Having no money to pay off outstanding debts or lease space, the University Club moved out of Brevoort Place in late 1867.[19] The club was nearly dormant for the next twelve years, with low membership and no permanent clubhouse. In 1869, the club met in the rooms of Luther M. Jones at 32 Waverly Place, and George V. N. Baldwin was elected as president. The next year, the University Club met at the office of F. E. Kernochan at 23 Broadway, and in 1871 the members voted to not seek any more clubhouses or elect any new members. Though club records are inconsistent, the members met in late 1871 at 81 Fifth Avenue; Kernochan's house, on 18 West 33rd Street; and George St. J. Sheffield's house, at 11 East 42nd Street. With 28 members in 1872, the club often met for dinners, and its meetings tended to be "more entertaining than serious".[20] By late 1874, the club had dwindled to 24 members and existed as the University Dining Club.[21] The club met at its treasurers' office at 120 Broadway, the Equitable Life Building, for six years in the 1870s, though this fact was not acknowledged until 1879.[22] Reorganization and growth The news media reported in December 1878 that the University Club was to resume activities.[23][24] The board of officers were planning to elect 200 new members, but The New York Times reported: "It is believed that there will be no difficulty in securing a membership of a thousand, if so large a number seems desirable."[23] The first printed list of newly elected members, published early in 1879, included almost 300 names, which was quickly expanded to 502.[25] The members appointed a committee in March to search for a new clubhouse and an official club restaurant.[26][27] The constitution of the club was modified in April and May to accommodate the additional memberships.[25][28] Henry Hill Anderson was elected as the president,[29] and membership was initially capped at 750.[30] In May 1879, the University Club leased the John Caswell residence at Fifth Avenue and 35th Street for five years.[31][32] The residence was a freestanding four-story brick building.[33] Club member Robert H. Robertson renovated the house to accommodate the club. The ornately decorated building contained a lounging room, a dining room, and a piazza on the first floor, with additional functions on the upper stories.[31][33] Another member, Charles Follen McKim designed a flag for the club,[31] which moved into its new quarters in June 1879.[33] One year after reorganization, the club had 689 members.[34] The University Club's members voted to authorize $10,000 in interest-paying securities in November 1880.[35] While at the Caswell residence, the University Club formed its library.[7] The University Club quickly outgrew the Caswell house and began planning improvements in 1881. The club's council first proposed extending the lease and building an annex on an adjacent vacant plot, but this failed. The council then proposed buying the house for $500,000 in May 1883, also unsuccessfully.[36] Ultimately, the club signed a lease for Leonard Jerome's residence at 26th Street and Madison Avenue, the Jerome Mansion,[21] in November 1883.[37][38][39] The club was thus allowed to pay $22,500 a year for five years with the option for a five-year extension at $24,000 a year.[38][40] The University Club bought some of the furniture from the house's previous occupant.[40][41] The annual meeting of May 17, 1884, was held in the new clubhouse.[42] The club built a kitchen on the roof, above the theater attached to the house.[40][42] The house's ground floor had a cafe, billiard room, and bowling alleys, while the second floor had a lounge. There was a library on the mezzanine and, for the first time, bedrooms for members to sleep overnight.[43] Some improvements to the house were postponed until 1886, when the theater was converted into a dining room and an elevator was installed[44] to designs by C. C. Haight.[45] Anderson retired as president of the club in 1888, and George Absalom Peters was elected as the club's new president.[46][47] In the same year, the club leased the Jerome Mansion for another five years.[46] At the annual meeting in 1889, the club's council established a fund for a permanent clubhouse building.[48] James W. Alexander was elected as club president in 1891.[49][50] The club had 1,884 members by 1893, and the Jerome Mansion was not large enough to fit all the members. The president was authorized to lease an adjacent house on Madison Avenue, owned by the Stokes family, but this never happened. In October 1893, the Jerome Mansion lease was extended five years, and around the same time, membership was increased to 2,100.[51] Permanent clubhouse buildingBy the mid-1890s, the University Club had no vacancies in its membership and hundreds of people on a waiting list to join. However, the Jerome Mansion was becoming too small to meet the club's needs.[7][52] As early as 1893, the club had considered buying the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 54th Street was part of the old campus of St. Luke's Hospital,[53][54] which had moved to Morningside Heights, Manhattan, in 1893.[55] A real-estate speculator had offered to buy all 32 land lots on the old St. Luke's campus for $2.4 million, or $75,000 per lot. The hospital's trustees had rejected an offer from the University Club to buy only eight of these lots at $93,750 each, and the University Club rejected the trustees' counter-offer of $125,000 for each of the eight lots.[56] Planning and construction At the meeting of February 1896, a five-person committee was created to identify sites for a new clubhouse.[53] The club had a dedicated clubhouse fund of $300,000.[57][58] On May 4, 1896, the committee announced that it had examined several sites and recommended three sites.[53] The northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 54th Street, on the old campus of St. Luke's Hospital, was again suggested.[55] Two other sites along Fifth Avenue were also suggested: one at the southeast corner with 37th Street and one at the southeast corner of 44th Street.[b] The 54th Street parcel could be bought for $675,000, while the 37th and 44th Street parcels were offered by the Stevens family under 20-year leases at $35,000 per year.[53][56] The council moved to recommend the 54th Street site on May 5, 1896, as that offer expired in 48 hours.[53] Conflicting explanations are given for why the 37th and 44th Street parcels were rejected. The historian John Tauranac and a club historian write that the council preferred to not lease their space,[53][56] but The New York Times reported that these parcels were considered "the wrong corners" because northwest and northeast corner sites enjoyed more direct sunlight.[59] The next week, the members at large voted to approve the 54th Street site, which consisted of five lots.[57][58][60] With the assurance that a new clubhouse would be developed, the council was finally able to increase its membership.[61] Charles F. McKim, who was a club member,[62] was selected as the primary architect of the new clubhouse in June 1896.[63] The next month, the club's council authorized the purchase of two additional lots immediately adjacent to the property from the Rockefeller family, one on 54th Street and an adjacent tract on 55th Street.[63][64][65] McKim's firm McKim, Mead & White filed plans for the building in May 1897,[66][67] and construction began the same month.[66][68] Charles T. Wills was hired as the general contractor.[69] The building's predicted cost was over $2 million, including land and furniture.[66][70][69] The club took out two mortgage loans, one for $1.2 million[70][71] and another for $350,000.[70] The development of the new clubhouse was described in the New-York Tribune as part of a trend of clubs relocating uptown.[72] By late 1898, the clubhouse was nearly completed.[73] Opening and early 20th centuryThe members were notified in April 1899 that the Jerome Mansion clubhouse was to be closed.[74] The new clubhouse at Fifth Avenue and 54th Street was completed by May 1899.[75][76] The new club house was officially opened on May 17, 1899, with a dinner.[74] Reactions from local media were positive. Brooklyn Life newspaper said "One is particularly impressed with the exterior beauty of the new home of the University Club" and said the structure lacked "nothing in the way of comfort or history".[77] The New York Times said that "New York may well be proud of her newest building, the University Club structure",[4] and the Sun labeled it "One of the Finest Buildings of the Kind" in the United States in a headline.[78] To fund the new building, the club's annual membership fee increased by $75 the year after the clubhouse opened.[73] Though the expanded clubhouse allowed 1,700 resident members and 1,300 non-resident members, the resident capacity had been reached shortly after the club was completed.[79] By the end of 1901, the club had 2,800 members, of which nearly 2,000 came from four colleges: Columbia, Yale, Harvard, and Princeton.[80] Alexander resigned as president of the University Club in 1899, having overseen the completion of the clubhouse.[79][81] Lawyer Charles C. Beaman was elected as the president at the annual meeting in 1899, but he died at his Manhattan home the following year.[82][83] Retired judge Henry E. Howland, characterized in The New York Times as "one of the best known lawyers in America",[84] was elected as president in 1901.[79][85] In the early years of the new clubhouse, the University Club hosted several events, such as dinners featuring Prince Henry of Prussia in 1902,[86] a Chinese imperial party in 1906,[87] and mayor George B. McClellan in 1908.[88] After Howland stepped down as president in 1905,[89] retired attorney Edmund Wetmore, who had been one of the club's cofounders,[21][90] served as the club's president until 1910.[89][91] Afterward, Benjamin Aymar Sands served as club president until 1913, when he was replaced by lawyer Thomas Thacher.[92] In March 1916, the University Club obtained an option to buy two lots on 54th Street and 55th Street, which adjoined the existing clubhouse.[93][94][95] The new acquisition on 54th Street was directly across from the houses of John D. Rockefeller and his son John Jr.[93] at 4 and 10 West 54th Street respectively.[96] McKim, Mead & White filed plans for a 50-by-200-foot (15 by 61 m) annex to the clubhouse in July 1916. The addition was projected to cost $100,000 and would provide more bedrooms for members and their guests.[97][98] In June 1917, the club received a $1 million mortgage to fund the construction of the annex.[99][100] Thacher was replaced as club president in 1919 by A. Barton Hepburn.[92] After Hepburn's death in 1922,[101] H. Hobart Porter was elected as club president that year.[102][103] McKim, Mead & White designed a further expansion to the building in 1927.[104] George W. Wickersham was the club's president from the mid-1920s until 1930, when he was replaced by electromechanical engineer Michael Idvorsky Pupin.[105][106] Mid-20th century to presentWomen were banned from the clubhouse altogether until 1928, when they were allowed to attend Sunday evening suppers, as well as the biannual ladies' supper. In 1940, the clubhouse hosted a couples' dance for the first time in its history.[107] By 1980, the club's council was considering women as full members; even though the club's bylaws did not prohibit women, none had ever been accepted as members. At the time, the New York City Council was contemplating a bill that would prevent gender- or race-based restrictions for private clubs.[108][109] Opponents of the proposal said the club was meant for men and that accepting women would cause pressure for the admissions committee.[109] The council had given women the right to use the private library in early 1980 without consulting the members. At a vote that May, the members voted to prevent women from obtaining full memberships.[110] The city government enacted its antidiscrimination law in 1984[111] and opened an investigation into the University Club in 1986.[112] Fifty-three percent of members voted in January 1987 to ignore that law,[113] though some opponents said they voted to protest the city government regulating what the club could do.[114] To comply with the law, the club was considering firing many of its waitstaff.[115] Finally, in June 1987, the club voted to allow women to become members.[3][116] Within a year, 16 women had been admitted as members, out of 4,000 total members.[117] The clubhouse accumulated dirt throughout its history until it was cleaned in 1984. The annex was cleaned before the main building was.[118] The facade, which had darkened to a gray hue, was restored to its original color,[119] although architectural critic Christopher Gray said the change "was not necessarily an aesthetic improvement".[59] In 2005, the clubhouse underwent renovation and was covered with scaffolding. The work involved removing the balconies and bronze railings for restoration. The restoration architects intended to preserve the bronze, which had oxidized over time into a dark green color.[59] In 2012, Manhattan Community Board 5 approved a modification of the clubhouse's main entrance.[120] With the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States in 2020, many members relocated to the suburbs, prompting the club to fire some workers.[121] Clubhouse McKim, Mead & White designed the University Club's clubhouse,[122][123] and William M. Kendall of that firm was also involved in the design process.[124] The architects drew inspiration from their education at the École des Beaux-Arts.[125][126] It was designed like a 16th-century palazzo in the Mediterranean Revival and Italian Renaissance styles, although the building also has distinct architectural features not inspired by the palazzo style.[125][127][128] The building's design resembled that of the Palazzo Rucellai and the Palazzo Medici Riccardi.[62] The current clubhouse is composed of two adjoining structures. The original nine-story building at Fifth Avenue and 54th Street measures 100 by 140 feet (30 by 43 m) at ground level.[78][129] The annex to the west of the original clubhouse is six stories high and 25 feet (7.6 m) wide on 54th Street, while it is nine stories high and 27 feet (8.2 m) wide on 55th Street.[99] Various contractors were hired to construct the clubhouse. Post & McCord were given the iron contract while the Norcross Brothers were given the granite contract.[68] McKim, Mead and White also commissioned Edward F. Caldwell & Co. to provide light fixtures for the University Club's clubhouse.[130] The addition was constructed by general contractor Marc Eidlitz & Son.[100] SiteThe University Club's clubhouse is in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It is on the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue to the east and 54th Street to the south. The land lot is L-shaped and covers 22,650 square feet (2,104 m2), with a frontage of 100 feet (30 m) on Fifth Avenue and a depth of 175 feet (53 m) along 54th Street.[131] The westernmost section of the lot extends the entire depth of the city block to 55th Street.[131] The lot originally had a frontage of 100 feet on Fifth Avenue and 150 feet (46 m) on 54th Street.[62][63][66] An additional 25-foot-wide strip of land on 54th and 55th Streets, extending 200 feet (61 m) deep between the two streets, was obtained in 1916.[94] With this purchase, the University Club's site assumed its current frontage of 175 feet on 54th Street and 52 feet (16 m) on 55th Street.[94][100] To the west, the clubhouse abuts the residences at 5, 7, 9–11, 13 and 15 West 54th Street and the Rockefeller Apartments, while to the north, it wraps around The Peninsula New York hotel at Fifth Avenue and 55th Street.[131][123] The clubhouse is also near Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church and 712 Fifth Avenue to the north, the St. Regis New York hotel to the northeast, 689 Fifth Avenue and 19 East 54th Street to the east, the William H. Moore House to the southeast, and Saint Thomas Church and the Museum of Modern Art to the south.[131] Facade The original nine-story facade[c] is clad with pink Milford granite.[127][129] The granite is divided into rusticated blocks, though the grooves of the rustication are less deep on upper stories.[129] The facade is divided into three tiers,[59][122][132][133] with horizontal band courses separating the bottom, middle, and top sections of the building.[125][127][128] Each of these sections, measuring three stories high, have double-height arched windows at the bottom.[127][129] There are also carved marble shields on the third and sixth stories, which depict the eighteen universities or colleges that most of the members attended.[78][129][d] One of the institutions, the United States Naval Academy, had no seal, so the architects invented one for the facade.[134] Beneath the shields are inscriptions with the universities' names in Latin, sculpted by Daniel Chester French.[129][135] These seals were commissioned at a cost of $1,000 each (equivalent to $36,624 in 2023) and were funded by members who were alumni of the respective colleges.[73] The corners of the building have slightly projecting rusticated piers reaching its full height.[136]  On the first story, there are six arched windows on 54th Street, three on each side of the decorative main entrance; there are also five similar windows on Fifth Avenue.[128][137][138] There are keystones above each of the window, which depict mythological characters such as satyrs, nymphs, and the gods Pan and Bacchus.[75] The 54th Street entrance consists of a massive arch flanked by a pair of rusticated columns, above which is a lintel,[125][128][137] as well as a carved head in the archway's keystone, which depicts Pallas.[78] The archway as a whole is designed in the Doric order. The columns consist of alternating sections with two primary motifs: decorated flutes and bands ornamented with foliage that encloses the club's monogram, as well as the initials of universities and colleges from which the club's members graduated. The entablature is adorned with triglyphs, metopes, and mutules, which are designed to harmonize with the columns.[137][138] The third-story mezzanine contains rectangular openings above each of the windows (eight on 54th Street and six on Fifth Avenue), which alternate with French's carved marble shields.[128][129][138] There are four shields each on 54th Street and Fifth Avenue.[139] The middle section also has double-height arched windows on the fourth story: seven on 54th Street and five on Fifth Avenue. Outside some of these arched windows are ornate balconies with iron railings.[125][128] These consist of a long balcony on Fifth Avenue (spanning the center three windows there) and three short ones on 54th Street (spanning one window each).[137] These balconies have Italian Renaissance and Roman motifs,[136] consisting of panels enclosing pierced acanthus scrolls.[137] Above each individual window are keystones that depict poets and philosophers such as Homer, Socrates, Goethe, Dante, and Shakespeare.[75] The row of arched windows is topped by rectangular openings on the sixth floor, which alternate with the carved college shields.[125][128] There are six shields on 56th Street and four on Fifth Avenue.[139] Above the center window on 54th Street is the club's shield, sculpted by Kenyon Cox.[73][135][138][140] The top section has double-height arched windows at the seventh story, arranged in the same manner as the fourth-story windows.[125][128] The seventh story has similar ornate balconies to the fourth story, but there is a single balcony spanning the center window at 54th Street and a three-bay-wide balcony spanning the three center windows on Fifth Avenue.[137] The ninth-story attic windows are embedded within the deep cornice that runs above the building.[125][128][137] The cornice is decorated with Italian Renaissance and Roman motifs,[136] with dentils, eggs and darts, and brackets and lions' heads.[137] The roof of the building is about 122 feet (37 m) above the pavement,[129] though it had been planned to be 128.5 feet (39.2 m).[66][141] On top of the clubhouse building is a roof garden.[73][78] The roof is entirely laid in stone and surrounded by a tall stone coping.[75] Some sources considered the roof garden as a tenth floor since it is partially roofed over.[78] InteriorThe interior arrangement was designed with three double-height main floors and three mezzanine stories above them. The first, fourth, and seventh stories were the main floors respectively contained the lobby, library, and dining rooms.[59][129] The center of the building on each main floor is designed with a square hall containing marble columns.[66][141] All stories are connected by elevators.[59] The elevators and staircase are placed in the northwest corner of the building, and the elevators from the outset were meant to provide the primary access to each floor. The lack of a grand staircase allowed the building to be designed more efficiently.[142][78][143] The staircase, connecting all the stories of the building, is made of marble with metal balustrade and wooden handrail.[75] The clubhouse also included amenities that were typical of other clubhouses, such as a swimming pool, library, lounges, and guest rooms.[69] First through third floors The first floor of the Club is occupied by the central hall, with a lounging room on the east side and an office and cafe on the west side.[140][144] The hall is rectangular in plan, measuring 25 feet (7.6 m) high, 60 feet (18 m) long, and 50 feet (15 m) wide. It has a vaulted ceiling supported by dark green Connemara marble columns[e] with gilded Doric capitals at their tops.[4][75][78] The hall is also surrounded by piers, which form a peristyle, behind which is an aisle with a lower vaulted ceiling.[140] Along the outer walls are Connemara marble pilasters, between which are Italian mosaic panels in several different colors. These pilasters support a decorative entablature.[4][140][144] There are doorways leading to surrounding rooms, which contain white Norwegian-marble architraves above them.[138] The floor consists of Italian and Vermont marble panels interlaid with foreign marbles. Immediately opposite the entrance, on the north wall, is a fireplace topped by a sculpted panel by Charles E. Keck.[138][140][144] Atop the east and west walls, above the doorways leading respectively into the lounging room and the office, are gold reliefs depicting the eagle and wreath of Trajan's Forum.[4][142] Leading from the central hall's east wall is a hallway with a candelabra designed by Edward F. Caldwell.[142] Three arched portals at the end of the hallway lead into the main lounging room (now the Reading Room), which occupies the full length of the Fifth Avenue facade.[4][142][144] The Reading Room contains a gilded ceiling with a central oblong panel surrounded by smaller panels.[75] The room was designed like a Roman Renaissance apartments. The walls have with pilasters reaching from the floor to the entablature, with the arched windows in between along the south and east walls. The arched portals on the west wall have marble door architraves, and the fireplace also has a marble architrave.[142] The pilasters have an ornate entablature, the paneled ceiling is gilded, and the frieze on the walls has marble panels.[142][144] The pilasters and woodwork are of Italian walnut, while the walls are fitted with a deep-toned red velvet.[4][138][142] The room was originally decorated with red, green, blue, and gold colors and had paintings.[145] In addition, there was red velvet furniture.[4][75] The southwest corner of the building had a cafe decorated in wood and leather.[75][142] The cafe measured 40 feet (12 m) square and originally had leather-covered chairs and lounges and dark wood tables. The ceiling of the cafe had ivory white paneling.[75] As of 2021, the Dwight Room takes up the first floor and has luncheon buffets, cocktails, and afternoon tea.[146] Other rooms on the first floor included the coat room, office, and strangers' reception room.[78] A staircase ascends from the northwest corner of the first floor. The second-story landing has a billiards room. The third-story landing was furnished with 17 bedrooms, each with their own bathroom. These were rented to members for up to a week at a time.[75][78] Fourth through sixth floors  The fourth floor contains the library, reading and writing rooms, and council chamber.[147] In the center is an atrium similar in dimension to that of the first floor. The design was characterized by contemporary media as "Pompeian" in style, with brightly colored columns and walls and a neutrally tinted ceiling.[143][144][148] The room's main architectural features are ivory-toned, with a background of panels in rich reds and russets, as well as two niches containing statues. The center of the south wall has an Istrian-style doorway leading to the center of the club's private library.[147][148] There are marble sculpture busts depicting ancient philosophers Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Plato.[149] These were sculpted in Rome by M. Ezekiel and were presented to the club in 1905 by member John Woodruff Simpson.[150] The center of the east wall has another doorway leading to the magazine room, and the center of the north wall leads to a large room with a groin vault.[147] The library measures 135 feet (41 m) long, 34 feet (10 m) wide, and 24 feet (7.3 m) high.[75] According to a club brochure, the library has approximately 100,000 books and periodicals;[151] a source from 1994 described the library as having 130,000 volumes.[138] It is decorated in English oak with marble wainscoting.[144][152] There are five alcoves on each of the north and south walls.[75][148] The alcoves measure 9 feet (2.7 m) deep[153] and contain walnut bookcases, except that the center alcove on the north wall leads from the atrium.[75][149] The windows on the south side are lit by the windows along 54th Street.[153] The space between the alcoves on opposite walls is 16 feet (4.9 m) wide and contains a vaulted ceiling divided into five sections.[148] The ceiling was originally painted white, but one club member, the banker Charles T. Barney, paid for murals on the ceiling.[134] The library's ceiling and walls are decorated with a series of murals by Harry Siddons Mowbray.[149][152][154] The pieces symbolize various subjects[f] and are composed both of original work by Mowbray and copies of Pinturicchio.[155] Small staircases between the vaults lead to balconies above each alcove on the fifth floor, which contain access to the upper shelves.[143][144][149] Above the openings leading to these staircases are niches with bronze sculpture busts.[149][156] The design in general was meant to be evocative of the Borgia Apartments at the Vatican.[151][155][156] The gallery is bounded on the east and west by additional rectangular study rooms, each with portraits and bookshelves.[149][143] North of the east study room, and east of the atrium, is the magazine room, which is at the center of the Fifth Avenue facade. The magazine room has a vaulted ceiling divided into segments. The ceiling has an ivory hue while the walls are of buckram.[143][147] The magazine room is generally decorated in dark green and red.[143][144] Beyond that is a conversation room with red tapestries on the walls and a hemispherical white-tinted ceiling.[143][157][144] The corners of the conversation room have pilasters topped by silver capitals.[143] The main atrium and the magazine room were decorated in collaboration with Elmer E. Garnsey.[144][147] The fifth floor, the mezzanine above the library, contains a small smoking room in the northwest corner. It has a beamed ceiling and wainscoting, and a mantelpiece in the Dutch style.[78][143][147] It also contains a room that at one point housed the College Memorabilia collections.[147] The sixth floor, as with the third floor, had seventeen bedrooms.[78][143][147] Seventh through ninth floorsThe hall at the center of the seventh floor has paneled oak walls, a flat ceiling containing low relief panels, and three portals leading to the main dining room.[147] The hall could be used as a overflow dining room when the main dining room was already filled with guests.[157] The main dining room on the seventh floor occupies the entire length of the 54th Street facade.[156][157][147] The main dining room has a ceiling 34 feet (10 m)[143][158] or 37 feet (11 m) high.[156] The room is 136 feet (41 m) long and is divided into three sections: a full-height center section, as well as sections with lower ceilings to the west and east. The walls have pilasters and columns made of oak; on the southern wall, the panels and arches of the windows alternate with the pilasters and columns. On the northern wall, there are lunettes containing round panels with elaborately carved ornamentation; these were designed to contain paintings. The columns and pilasters support the main entablature and deep attic, and the engaged columns at the entrance support a balcony for musicians,[144][158] a feature also present in the nearby Villard Houses.[156] The attic is treated with decorative pilasters and panels, some of which contain animals' heads.[143][158] The main dining room also has large fireplace mantels at either end.[157][158] The mantel on the west end was reportedly several hundred years old. The floor is made of stone.[75][143] The northwest corner of the seventh floor is occupied by the council room and an adjoining anteroom.[158] The council room measures 40 by 40 feet (12 by 12 m)[157] and is finished in Italian walnut with a coved ceiling. The walls have Doric pilasters with intervening panels of wood and mirrors, the chimney breast being carried to the ceiling, and surmounted by elaborate wood-carving. The ceiling is divided into lozenge-shaped panels depicting figures upon a blue background. Other parts of the ceiling, including the ribs, are colored gold.[158] The council room's wall space was nearly entirely fitted with mirrors.[143] Above the main dining room is an eight story with a kitchen and storerooms.[75][78][143] The ninth story contains dining rooms for private parties.[78] it was designed as four private rooms, which were separated by curtains but could be combined.[143] BasementFrom the first floor, a staircase leads to the basement.[159] The basement was designed with bowling alleys and a Roman bath.[66][78][141] On the 54th Street side is the clubhouse's mechanical plant,[73][160] which had facilities for power, heat, light, ventilation, and ice.[144] On the Fifth Avenue side is a swimming pool with equipment for full Turkish bath.[73][160] The swimming pool itself is 48 by 17 feet (14.6 by 5.2 m) wide and is built of white marble, with sidewalls made of white glazed brick.[160] The swimming pool contains a fountain shaped like a brass lion's head, while the ceiling of the pool area is painted as a trompe-l'œil blue sky.[159] Surrounding the bath are dressing rooms, saunas, and a lounging and smoking room at one end.[157] A basement in the annex contained the bicycle storage room and wine cellar.[73] Memberships The club, nicknamed "The U" by its members,[159] ranked among New York City's most exclusive social clubs by the 21st century.[161][162][163] The club is not affiliated with any other University Club or college alumni clubs.[3] Under the 1879 constitution, the club's executive powers were held by a 20-member council[25][164] and membership was handled by a 21-member council.[25][165] All members were required to have graduated from a postsecondary institution at least three years prior or received an honorary A.M. or LL.D.; in the latter case, the graduation requirement was waived. In addition, Military Academy and Naval Academy graduates were eligible.[35][166] Before 1885, the required minimum period of graduation was five years.[167] The constitution initially allowed any honorary degree holder to become a member, but the constitution was amended in 1882 to restrict the criterion to certain degrees.[168] As of 2021[update], all members were required to have earned a baccalaureate degree from any college or university that had accreditation, as long as they sent a proposal for admission form and letters of recommendation from existing members.[146] In the 1879 constitution, it was provided that all members who joined before May 10, 1879, would pay a $50 initiation fee (equivalent to $1,635 in 2023), and all members after that date would pay $100 (equivalent to $3,270 in 2023). Members who were residents of New York City paid $50 in annual dues and non-resident members paid $25.[169] In 1895, life memberships were introduced; members of at least ten years could purchase life memberships for $750 (equivalent to $27,468 in 2023). The first life membership was issued to philanthropist Joseph F. Loubat that year.[170] In the 21st century, modern membership fees and statistics were generally not publicized,[161] but The New York Times reported in 2015 that annual fees ranged from $1,000 to $5,000.[162] The maximum number of members has varied over time, and the 1879 constitution originally restricted the club to 750 members, without apportionment based on whether a member lived in the city.[30] By 1914, the club's constitution provided for a maximum of 2,000 resident members and 1,500 non-residents, including military personnel.[169] By the 1980s, when women were allowed to become members, the University Club had 4,000 members.[3] Members were also allowed to bring visitors with them. The club's constitution initially allowed visitors only if they would ordinarily also be eligible for membership, if they resided within 30 miles (48 km) of New York City Hall and worked in the city. In 1886, the rule that required visitors to be eligible for membership was removed.[171] By the 21st century, the University Club's clubhouse was being used frequently for finance-related events.[163] House rulesThe University Club maintains a dress code as part of its house rules. As of 2021[update], male members and guests must wear jackets and dress shirts and were recommended to wear ties. Female members and guests had to wear tailored "clothing meeting similar standards", such as suits, dresses, or skirts with sweaters or dress shirts.[163][172] The dress code prohibits informal clothing. During weekends, members could wear polo shirts instead of jackets in several rooms, and members and guests could wear prohibited clothing if they used the secondary entrance at 3 West 54th Street to access a guest room or athletic facility.[172] The University Club continues to allow nude swimming for men, unlike other private clubs in New York City, which had banned the practice.[159][163] The University Club's house rules also restrict electronic devices, photography, and the use of the club's name. According to the house rules, cellphones are required to be silenced and could not be used except in telephone booths or private rooms. Additionally, other devices such as laptops could be used only in the library or other parts of the clubhouse. The house rules also required members or guests to obtain permission before photographing the club or describing its facilities and activities. The club's house committee had to approve any media appearances involving the club. Smoking and bringing animals into the clubhouse was also generally prohibited under the rules.[172] The club has strictly enforced regulations on guests, as in 1997, when then-U.S. first lady Hillary Clinton and reporter Cindy Adams were ejected after they broke a rule regarding discussion.[173][174] Club seal The University Club had no official seal until 1883, when the secretary was asked to create a seal "with the name of the Club in a circle with the date of incorporation in the centre".[175] With the construction of the 54th Street clubhouse, the club adopted a more ornate seal in 1898.[175] The design was made by Kenyon Cox and the escutcheon on the facade was sculpted by George Brewster very closely to the original drawings.[176] The design represents two Greek youths, their hands clasped in friendship. One of them holds a tablet bearing the word "Patria". The other holds a torch representing learning as well as eternity. The flame was inspired by Ancient Greek mythology, in which a succession of runners carried a burning torch and passed it to each other; this was meant to symbolize how learning was passed down between generations of scholars. Behind the two youths is a figure of Athena, the Greek deity of wisdom, on an altar. A Greek language inscription on the club seal translates to "In Fellowship Lies Friendship".[176] Notable membersFounding membersThe University Club's articles of incorporation on April 28, 1865, list the following individuals:[21][90]

The University Club's founding membership includes the men who participated in the predecessor organization, the Red Room Club, from 1861 to 1864. These members were all alumni of Yale and graduated from 1859 to 1863.[5]

Other membersIn the first year book, the names on the rolls included:[14]

Over the years, many notable professionals have been admitted as members. A partial list includes:

See also

ReferencesNotes

Citations

Sources

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to The University Club of New York.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||