|

United States presidential debates

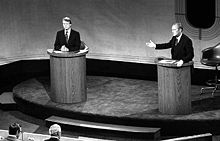

During presidential election campaigns in the United States, it has become customary for the candidates to engage in one or more debates. The topics discussed in the debate are often the most controversial issues of the time, and arguably elections have been nearly decided by these debates. Candidate debates are not constitutionally mandated, but they are now considered an intrinsic part of the election process.[1] The debates are targeted mainly at undecided voters; those who tend not to be partial to any political ideology or party.[2] With the exception of the debate between 45th President Donald J. Trump and 46th President Joseph R. Biden Jr. held on June 27, 2024, presidential debates are typically held late in the election cycle, after the political parties have nominated their candidates. The candidates typically meet in a large hall, often at a university, and usually before an audience of citizens; however, to accommodate debate rules and guidelines requested by the Biden 2024 campaign[3] for the June 27, 2024 debate between Trump and Biden, no audience of citizens was present. The formats of the debates have varied, with questions sometimes posed from one or more journalist moderators and in other cases members of the audience. The debate formats established during the 1988 through 2000 campaigns were governed in detail by secret memoranda of understanding (MOU) between the two major candidates; the MOU for the 2004 debates was, unlike the earlier agreements, jointly released to the public by the participants. Debates have been broadcast live on television, radio, and in recent years, the web. The first debate for the 1960 election drew over 66 million viewers out of a population of 179 million, making it one of the most-watched broadcasts in U.S. television history. The 1980 debates drew 80 million viewers out of a population of 226 million. Recent debates have drawn smaller audiences, ranging from 46 million for the first 2000 debate to a high of over 67 million for the first debate in 2012.[4] A record-breaking audience of over 84 million people watched the first 2016 presidential debate between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, a number that does not reflect online streaming.[5] Since 1960, no year has gone higher than 3. HistoryThe first general presidential debate was not held until 1960, but several other debates are considered predecessors to the presidential debates. Lincoln–Douglas debatesThe series of seven debates in 1858 between Abraham Lincoln and Senator Stephen A. Douglas for U.S. Senate were true, face-to-face debates, with no moderator; the candidates took it in turns to open each debate with a one-hour speech, then the other candidate had an hour and a half to rebut, and finally the first candidate closed the debate with a half-hour response. Douglas was later re-elected to the U.S. Senate by the Illinois legislature. Lincoln and Douglas were both nominated for president in 1860 by the Republicans and Northern Democrats, respectively, and their earlier debates helped define their respective positions in that election, but they did not meet during the 1860 presidential election. Early presidential primary candidate debatesWendell Willkie became the first 20th century presidential candidate to challenge his opponent to a face to face debate when in 1940 he challenged President Franklin D. Roosevelt, but Roosevelt refused.[citation needed] In 1948, presidential candidate debates became a reality when a radio debate was held in Oregon between Republicans Thomas E. Dewey and Harold Stassen during the party's presidential primary.[6][7] The Democrats followed suit in 1956 with a televised presidential primary debate between Adlai Stevenson and Estes Kefauver,[8][9] and in 1960 by one between John F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey.[10] In 1956, during the 1956 presidential campaign, University of Maryland student Fred Kahn led an effort to bring the two major presidential candidates, Adlai Stevenson II, the Democratic nominee, and President Dwight Eisenhower, the Republican nominee, to the campus for a debate.[11] Various newspapers were contacted and numerous letters were sent in an effort to generate interest and garner support for the proposal. Former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt was among those who received a letter. Kahn later told Guy Raz during an All Things Considered interview on NPR in 2012 that she replied, saying, "not only would the students of the University of Maryland be interested, but also other students." Roosevelt said that she was going to forward Kahn's letter to James Finnegan, Adlai Stevenson's campaign manager.[12] In the end, no debate took place, but Kahn's effort received national press exposure, helping lay groundwork for the Kennedy–Nixon debates four years later during the 1960 presidential campaign.[11] 1960 Kennedy–Nixon debatesThe first general election presidential debate was 1960 United States presidential debates, held on September 26, 1960, between Senator John F. Kennedy, the Democratic nominee, and Vice President Richard Nixon, the Republican nominee, at CBS's WBBM-TV in Chicago. It was moderated by Howard K. Smith and included a panel composed of Sander Vanocur of NBC News, Charles Warren of Mutual News, Stuart Novins of CBS, and Bob Fleming of ABC News. At the outset, Nixon was considered to have the upper hand due to his knowledge of foreign policy and proficiency in radio debates. However, because of his unfamiliarity with the new format of televised debates, factors such as his underweight and pale appearance, his suit color blending in with the debate set background, and his refusal to use television makeup resulting in a five o'clock shadow, led to his defeat. Many observers have regarded Kennedy's win[neutrality is disputed] over Nixon in the first debate as a turning point in the election.[13][14] After the first debate, polls showed Kennedy moving from a slight deficit into a slight lead over Nixon. Three more debates were subsequently held between the candidates:[15] on October 7 at the WRC-TV NBC studio in Washington, D.C., narrated by Frank McGee with a panel of four newsmen Paul Niven of CBS, Edward P. Morgan of ABC, Alvin Spivak of United Press International,[16] and Harold R. Levy of Newsday, on October 13, with Nixon at the ABC studio in Los Angeles and Kennedy at the ABC studio in New York City, narrated by Bill Shadel with a panel of four newsmen in a different Los Angeles studio; and October 21 at the ABC studio in New York, narrated by Quincy Howe with a panel of four including Frank Singiser, John Edwards, Walter Cronkite, and John Chancellor. Nixon regained his lost weight, wore television makeup, and appeared more forceful than in his initial appearance, winning the second and third debates while the fourth was a draw,[neutrality is disputed] however the viewership numbers of these subsequent events did not match the high set by the first debate and ultimately did not help Nixon as he lost the election. 1976 presidential debate After the Kennedy–Nixon debates, it was 16 years before general election presidential candidates again debated each other face to face. During this interval intra-party debates were held during the 1968 Democratic primaries, between Robert F. Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy, and again during the 1972 Democratic primaries, between George McGovern, Hubert Humphrey, and others.[citation needed] The next presidential candidates debates occurred during the 1976 campaign, when President Gerald Ford, who had entered office two years earlier after President Richard Nixon resigned, agreed to three debates with his Democratic challenger, Jimmy Carter.[17][18] The 1976 debates, one on domestic issues, one on foreign policy, and one on any topic, were held before studio audiences, and, like the 1960 debates, were televised nationally. The League of Women Voters sponsored the debates.[19] This was a change from the Kennedy–Nixon debates, which had been sponsored by the television networks themselves.[17] Roughly an hour into the first televised debate, the broadcast audio coming from the Walnut Street Theatre and fed to all networks suddenly cut out, effectively muting the candidates in the middle of a statement by Carter. The two candidates were initially unaware of this technical glitch and continued to debate, unheard to the television audience. They were soon informed of this problem, and proceeded to stand still and silently at their lecterns for about 27 minutes, until the problem, a blown capacitor, was located and fixed, in time for Carter to briefly finish the statement he had begun when the audio cut out, and for both candidates to issue closing statements. The dramatic effect of televised presidential debates was demonstrated again in the 1976 debates between Ford and Carter. Ford had already cut into Carter's large lead in the polls, and was generally viewed as having won the first debate on domestic policy. Polls released after this first debate indicated the race was even. However, in the second debate on foreign policy, Ford made what was widely viewed as a major blunder when he said "There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe and there never will be under a Ford administration." After this, Ford's momentum stalled, and Carter won a very close election.[20][21] 1980 and 1984 presidential debates The League of Women Voters also sponsored the debates held in 1980 and in 1984.[22] In 1980, debates were a major factor again. Earlier in the election season, President Carter held a substantial lead over his opponents. Three debates between Carter, former California Governor Ronald Reagan and Illinois Congressman John B. Anderson (who was running as an independent), were originally scheduled; along with a single vice presidential debate between incumbent Walter Mondale, former CIA Director George Bush, and former Wisconsin Governor Patrick Joseph Lucey. Carter refused to debate if Anderson was present and Reagan refused to debate without Anderson, resulting in the first debate being between Reagan and Anderson only. The second debate and the vice presidential debate were both cancelled. Reagan eventually conceded to Carter's demand, and a single debate took place with only Carter and Reagan. With years of experience in front of a camera as an actor, Reagan came across much better than Carter in the debate and was judged by voters to have won by a wide margin. Reagan's debate performance likely helped propel his landslide victory in the general election. The Reagan campaign had access to internal debate briefing materials for Carter; the exposure of this in 1983 led to a public scandal called "Debategate".[citation needed] In 1984, former Vice President Walter Mondale won the first debate over President Ronald Reagan, generating much-needed donations to Mondale's lagging campaign. The second presidential debate was held on October 21, 1984, where Ronald Reagan used a joke, "I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent's youth and inexperience", which effectively stalled Mondale's momentum.[citation needed] Since 1976, each presidential election has featured a series of presidential debates. Vice presidential debates have been held regularly since 1984. Vice Presidential debates have been largely uneventful and have historically had little impact on the election. Perhaps the most memorable moment in a vice presidential debate came in the 1988 debate between Republican Dan Quayle and Democrat Lloyd Bentsen. Quayle's selection by the incumbent vice-president and Republican presidential candidate George Bush was widely criticized; one reason being his relative lack of experience. In the debate, Quayle attempted to ease this fear by stating that he had as much experience as John F. Kennedy did when he ran for president in 1960. Democrat Bentsen countered with the now famous statement: "Senator, I served with Jack Kennedy. I knew Jack Kennedy. Jack Kennedy was a friend of mine. Senator, you're no Jack Kennedy." 1992 presidential debatesIn 1992, the first debate was held involving both major party candidates and a third-party candidate, billionaire Ross Perot, running against President Bush and the Democratic nominee Governor Bill Clinton. That year, President Bush was criticized for his early hesitation to join the debates, and some described him as a "chicken". Furthermore, he was criticized for looking at his watch which aides initially said was meant to track if the other candidates were debating within their time limits but ultimately it was revealed that the president indeed was checking how much time was left in the debate. Moderators of nationally televised presidential debates have included Bernard Shaw, Bill Moyers, Jim Lehrer, and Barbara Walters. Presidential debates since 1992Saint Anselm College has hosted four primary debates throughout 2004 and 2008; it is a favorite for campaign stops and these national debates because of the college's history in the New Hampshire primary. Washington University in St. Louis, however, has hosted the presidential debates (organized by the Commission on Presidential Debates) three times (in 1992, 2000, and 2004), more than any other location prior to 2016, and also hosted one of the 2016 debates. The university was also scheduled to host a debate in 1996, but it was later negotiated between the two presidential candidates to reduce the number of debates from three to two. The university hosted the only 2008 vice presidential debate, as well.[23] Hofstra University, originally an alternate site, was named the host of the first presidential debate in 2016, after Wright State University withdrew with eight weeks remaining. This positioned Hofstra to be the only school to host presidential debates in three consecutive campaign cycles.[24] Most of the presidential/vice presidential debates have been moderated by ABC, CBS, CNN, FOX, NBC, and/or PBS. PBS currently holds the record for the most debates at 16.[25] Rules and formatSome of the debates can feature the candidates standing behind their podiums, or in conference tables with the moderator on the other side. Depending on the agreed format, either the moderator or an audience member can be the one to ask questions. Typically there are no opening statements, just closing statements. A coin toss determines who gets to answer the first question and who will make their closing remarks first. Each candidate will get alternate turns. Once a question is asked, the candidate has 2 minutes to answer the question. After this, the opposing candidate has around 1 minute to respond and rebut her/his arguments. At the moderator's discretion, the discussion of the question may be extended by 30 seconds per candidate. In recent debates, colored lights resembling traffic lights have been installed to aid the candidate as to the time left with green indicating 30 seconds, yellow indicating 15 seconds and red indicating only 5 seconds are left. If necessary, a buzzer may be used or a flag. Debate sponsorshipControl of the presidential debates has been a ground of struggle for more than two decades. The role was filled by the nonpartisan League of Women Voters (LWV) civic organization in 1976, 1980 and 1984.[19] In 1987, the LWV withdrew from debate sponsorship, in protest of the major party candidates attempting to dictate nearly every aspect of how the debates were conducted. On October 2, 1988, the LWV's 14 trustees voted unanimously to pull out of the debates, and on October 3 they issued a press release:[26]

According to the LWV, they pulled out because "the campaigns presented the League with their debate agreement on September 28, two weeks before the scheduled debate. The campaigns' agreement was negotiated 'behind closed doors' ... [with] 16 pages of conditions not subject to negotiation. Most objectionable to the League...were conditions in the agreement that gave the campaigns unprecedented control over the proceedings.... [including] control the selection of questioners, the composition of the audience, hall access for the press and other issues."[26] The same year the two major political parties assumed control of organizing presidential debates through the Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD). The commission has been headed since its inception by former chairs of the Democratic National Committee and Republican National Committee. Some have criticized the exclusion of third party and independent candidates as contributing to lower results for candidates such as the Libertarian Party or the Green Party. Others criticize the parallel interview format as a minimum of getting 15 percent in opinion polls of the CPD's choosing is required to be invited. In 2004, the Citizens' Debate Commission (CDC) was formed with the stated mission of returning control of the debates to an independent nonpartisan body rather than a bipartisan body. Nevertheless, the CPD retained control of the debates that year and in 2008. In 2024, the Democratic and Republican parties opted out of the CPD debates, in favor of debates in June and September produced by CNN and ABC News respectively. They later agreed to a vice presidential debate in October, which would be hosted by CBS News. All three debates were conducted with no audience or outside press, but would be made available to other broadcasters.[27][28] The RNC had withdrew from the CPD in 2022 because they felt it "[was] biased and has refused to enact simple and common-sense reforms to help ensure fair debates, including hosting debates before voting begins and selecting moderators who have never worked for candidates on the debate stage."[29]Joe Biden campaign manager Jen O'Malley Dillon stated that the debates had become too much of a "spectacle", the CPD was not consistently enforcing its rules in prior debates, and that the debates' timetable did not end before the start of early voting. This marked the first time the CPD had not sponsored a presidential debate since 1988.[30][31] Timeline

Sponsors, locations, moderators, panelists and viewershipSee alsoNotes

References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to US presidential debates.

Debate critics and activists

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||