|

Tayma

Tayma /ˈteɪmə/ (Taymanitic: 𐪉𐪃𐪒, TMʾ, vocalized as: Taymāʾ;[1] Arabic: تيماء, romanized: Taymāʾ) or Tema (Hebrew: תֵּימָן Tēmān (Habakkuk 3:3)) is a large oasis with a long history of settlement, located in northwestern Saudi Arabia at the point where the trade route between Medina and Dumah (Sakakah) begins to cross the Nafud desert. Tayma is located 264 km (164 mi) southeast of the city of Tabuk, and about 400 km (250 mi) north of Medina.[2][3] It is located in the western part of the Nafud desert. HistoryThe historical significance of Tayma is based on the existence there of an oasis, which helped it become a stopping point on commercial desert routes.[4] An important event was the presence there of Nabonidus, the last Neo-Babylonian emperor, who took residence there in the mid-6th century BC.[4] Bronze Age: Egyptian inscriptionRecent archaeological discoveries show that Tayma has been inhabited since at least the Bronze Age. In 2010, the Ministry of Tourism of Saudi Arabia announced the discovery of the Pharaonic Tayma inscription by Ramesses III about 60 kilometers northwest of Tayma. It read "'The King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands, User-Maat-Ra, beloved of Amun' -- 'The Son of Ra, Lord of Crowns, Ramesses, ruler of Heliopolis' -- 'Beloved of the "Great Ruler of All Lands'".[5] This was the first confirmed find of a hieroglyphic inscription on Saudi soil. Based on this discovery, researchers have hypothesized that Tayma was part of an important land route between the Red Sea coast of the Arabian Peninsula and the Nile.[citation needed] Assyrian, Babylonian, and biblical sources The oldest mention of the oasis city appears as "Tiamat" in Neo-Babylonian inscriptions dating as far back as the 8th century BC. The oasis developed into a prosperous city rich in wells and handsome buildings. Tiglath-pileser III received tribute from Tayma[6] and Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BC) named one of Nineveh's gates the Desert Gate, recording that "the gifts of the Sumu'anite and the Teymeite enter through it". It was rich and proud enough in the seventh century BC for Jeremiah to prophesy against it in Jeremiah 25:23: "Dedan, Tema, and Buz, and all those who have their hair clipped". It was ruled then by a local Arab dynasty known as the Qedarites. The names of two 8th century BC queens, Šamši and Zabibe, are recorded.[citation needed] Emperor Nabonidus (ruled c. 556–539 BC) conquered Tayma, and for ten years of his reign retired there to worship and search for prophecies, entrusting the kingship of Babylon to his son, Belshazzar.[6] Taymanitic inscriptions also mention that the people of Tayma fought wars with Dadān (Lihyan).[7][clarification needed] Cuneiform inscriptions possibly dating from the 6th century BC have been recovered from Tayma.[8] They are known as the Tayma stones. Tayma is mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible. The biblical eponym is Tema, one of the sons of Ishmael, after whom the Land of Tema is named.[citation needed] Jewish community: classical period and 12th centuryAccording to Arab tradition, Tayma was inhabited by a Jewish community during the late classical period, but whether they were exiled Judeans or the Arab descendants of converts is unclear. The Jewish diaspora at the time of the Temple's destruction, according to Josephus, was in Parthia, Babylonia, Arabia, as well as some Jews beyond the Euphrates and in Adiabene. In Josephus' own words, he had informed "the remotest Arabians" about the destruction.[9] So, too, in pre-Islamic poetry, Tayma is often referred to as a fortified city belonging to the Jews, as an anonymous Arab poet wrote, "Unto God will I make my complaint heard, but not unto man; because I am a sojourner in Taymā, Taymā of the Jews!"[10] As late as the 6th century AD, Tayma was the home of a wealthy Jew, Samaw'al ibn 'Adiya.[11][12] Tayma and neighboring Khaybar were visited by Benjamin of Tudela sometime around 1170. He claimed that the city was governed by a Jewish prince. Benjamin was a Jew from al-Andalus who travelled to Persia and Arabia in the 12th century. Crusader threatIn the summer of 1181, Raynald of Châtillon, Prince of Antioch and Lord of Oultrejordain, attacked a Muslim caravan near Tayma during a raid of the Red Sea area despite a truce between Saladin and Baldwin IV of Jerusalem.[13] ClimateIn Tayma, there is a desert climate. Most rain falls in the winter. The Köppen-Geiger climate classification is BWh. The average annual temperature in Tayma is 21.8 °C (71.2 °F). About 65 mm (2.56 in) of precipitation falls annually.

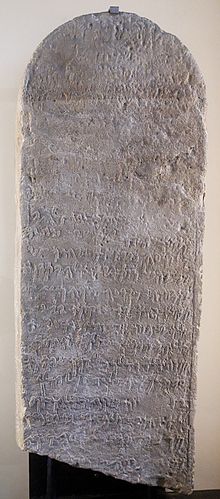

Archaeology The site was first investigated and mapped by Charles M. Doughty in 1877.[14] The Tayma stele discovered by Charles Huber in 1883, now at the Louvre, lists the gods of Tayma in the 6th century BC: Ṣalm of Maḥram and Shingala-and-Ashira. This Ashira may be "incorrect" for the name Ashima, according to Miller,[15] who also renders Śengallā.[16][17] Archeological investigation of the site, under the auspices of the German Archaeological Institute, is ongoing.[18][19] Clay tablets and stone inscriptions using Taymanitic script and language were found in ruins and around the oasis. Nearby Tayma was a Sabaean trading station, where Sabaean language inscriptions were found. EconomyHistorically, Tayma is known for growing dates.[20] The oasis also produced rock salt, which was distributed throughout Arabia.[21] Tayma also mined alum, which was processed and used for the care of camels.[22] Points of interest

See alsoReferences

Sources

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||