|

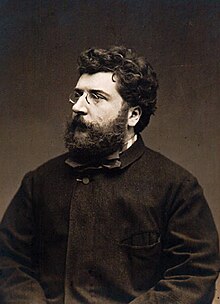

Symphony in C (Bizet) The Symphony in C is an early work by the French composer Georges Bizet. According to Grove's Dictionary, the symphony "reveals an extraordinarily accomplished talent for a 17-year-old student, in melodic invention, thematic handling and orchestration."[1] Bizet started work on the symphony on 29 October 1855, four days after turning 17, and finished it roughly a month later.[2] It was written while he was studying at the Paris Conservatoire under the composer Charles Gounod, and was evidently a student assignment. Bizet showed no apparent interest in having it performed or published, and the piece was never played in his lifetime. He used certain material from the symphony in later works, however.[3] There is no mention of the work in Bizet's letters, and it was unknown to his earlier biographers. His widow, Geneviève Halévy (1849–1926), gave the manuscript to Reynaldo Hahn, who passed it along with other papers to the archives of the conservatory library, where it was found in 1933 by Jean Chantavoine.[4][5] Soon thereafter, Bizet's first British biographer Douglas Charles Parker (1885–1970) showed the manuscript to the conductor Felix Weingartner, who led the first performance in Basel, Switzerland, on 26 February 1935.[6] The symphony was immediately hailed as a youthful masterpiece on a par with Felix Mendelssohn's overture to A Midsummer Night's Dream, written at about the same age, and quickly became part of the standard Romantic repertoire.[7] It received its first recording in 1937, by the London Philharmonic Orchestra under Walter Goehr.[8] FormWritten for a standard orchestra (without trombones), the work closely follows the classical symphonic form in four movements. The first and the last movement are in sonata form. HistoryBackgroundThe symphony is widely assumed to have been a student assignment, written toward the end of Bizet's nine years of study at the Conservatoire de Paris.[1] At the Conservatoire, Bizet had come increasingly under the influence of Charles Gounod, whose works in the first half of the 1850s—including Sapho (1851), Ulysse (1852) and the Symphony No. 1 in D major (1855)—had a strong impact on the young composer.[9] As Bizet would later write of this period: "Fifteen years ago [i.e. 1855/56], when I used to say "Sapho and the choruses from Ulysse are masterpieces", people laughed in my face. I was right".[10] In 1855, with Gounod his principal mentor, Bizet wrote his first three major compositions: the opera La maison du docteur, an overture, and the Symphony in C.[1] A year before Bizet started to compose the Symphony, Gounod had written his own first Symphony (in D), composed at the end of 1854 in the wake of a tepid response to his opera La nonne sanglante.[11] Gounod's Symphony in D proved a popular work, receiving at least eight performances in Paris alone within the space of a year.[11] Bizet was subsequently engaged with writing a transcription of the work for two pianos, one of a number of commissions to transcribe Gounod's work Bizet accepted to earn extra income.[1][12] This proximity to his mentor's work emerges in the close stylistic resemblance of Bizet's symphony with Gounod's; it may also explain why Bizet chose not to publish his symphony.[4][13] Similarities with Gounod's Symphony in D The numerous stylistic, orchestral, melodic and harmonic similarities between the Gounod and Bizet symphonies make it clear that Bizet was emulating and, in certain cases, directly quoting his teacher. As Howard Shanet, who revived Gounod's symphony with the Columbia University Orchestra in 1955, observed, "the first glance at [Gounod's] score ... made it clear that the young Bizet had copied all its most conspicuous features in his Symphony in C."[14] There are, in fact, so many references, parodies and quotations from Gounod in Bizet's work that it is likely the young composer was consciously paying homage to his celebrated teacher. His close involvement with Gounod's orchestral score in realising the two-piano transcription would have given Bizet the opportunity to explore many of its orchestral nuances and incorporate them into his own work and may explain why Bizet's first full-fledged symphonic work was such an unusually well-polished and well-orchestrated composition. As Bizet would later write to his former teacher: "You were the beginning of my life as an artist. I spring from you. You are the cause, I am the consequence."[15] This sentiment permeates the compositional spirit of the Symphony in C. All four movements of Bizet's symphony employ devices found in the earlier Gounod piece. The two inner movements are strikingly similar in form, rhythm and melodic shape.[16] First movement Second movement Third movement Final movement Finally, the scoring for both works is identical: a smaller, classical orchestra (omitting, for instance, piccolo, harp or trombones).[17] Although Bizet's symphony was closely drawing on Gounod's work, critics view it as a much superior composition, showing a precocious and sophisticated grasp of harmonic language and design, as well as originality and melodic inspiration. Since it has resurfaced, Bizet's Symphony in C has far outshone Gounod's work in the repertoire, both in terms of performance and number of recordings.[18] SuppressionThat the Symphony was never even mentioned in Bizet's extensive correspondence, let alone published in his lifetime, has given rise to speculation as to the composer's motives in suppressing the work. According to a 1938 correspondence from Bizet's publisher,

This explanation, however, was rejected by Shanet, who instead argued that Bizet was worried that his own work was too similar to Gounod's:

Since no evidence exists one way or the other, Bizet's motives must remain conjectural. However, the symphonic genre was not a popular one for French composers in the second half of the nineteenth century, who instead concentrated most of their large-scale efforts on theatrical and operatic music. Gounod himself observed: "There is only one way for a composer who desires to make a real name – the operatic stage."[21] This bias against formal symphonic writing was also entrenched within the culture of the Paris Conservatory, which considered the symphony to be (as in the case of Bizet's own) a mere student exercise on the path toward submissions for the Prix de Rome, the highest prize a young French composer could attain.[22] As the noted musicologist Julien Tiersot observed in 1903:

Instead, as Tiersot himself noted, French symphonic efforts gravitated toward the symphonic suite, of which Bizet's Roma Symphony was a pioneering example.[24] Indeed, while his youthful Symphony was written in less than a month, the Roma Symphony occupied Bizet for years, and he remained at his death unsatisfied with the work. Unlike the Symphony in C, Bizet tried to infuse his Roma Symphony with more gravitas and thematic weight. Of the two works, it is Bizet's student composition which has garnered much more critical praise.[1] It may also have been, as hinted at by the 1938 correspondence from Chevrier-Choudens, that Bizet intended to mine his student effort for material in what he saw as more serious compositions (including, possibly, two aborted symphonies written while in Rome).[25] The melodic theme of the slow movement reappears in Les pêcheurs de perles as the introduction to Nadir's air "De mon amie." And Bizet recycled the same melody in the trio of the Minuet from L'Arlésienne. In both cases, Bizet retained his original scoring for oboe. As noted by Chevrier-Choudens, Bizet also used the second theme of the finale in Act I of Don Procopio.[1] Finally, since he was only 36 when he died, it is entirely possible that had he lived, Bizet might have decided later to publish the work. Whatever the case, the work remained unpublished, unplayed, and unknown at Bizet's death, passing into the possession of his widow, Geneviève Halévy. Rediscovery and posthumous popularityAlthough Bizet's first biographer, Douglas Charles Parker, is widely credited with bringing the symphony to public attention, it was the French musicologist Jean Chantavoine who first revealed the existence of the work, in an article published in the periodical Le Ménestrel in 1933. Parker, alerted to its existence, informed the Austrian conductor Felix Weingartner, who gave the highly successful premiere in Basel in 1935. The work was published the same year by Universal-Edition.[5] Within a short time of its publication, the work had been widely performed. The musicologist John W. Klein, who attended its London premiere, found the work "enchanting" and "charming," a view that has been generally echoed since.[7] Although a student assignment, many musicologists find the symphony shows a precocious grasp of harmonic language and design, a sophistication which has invited comparisons with Haydn, Mozart, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Rossini, and Beethoven.[26] It received its first recording on 26 November 1937, by the London Philharmonic Orchestra under Walter Goehr.[8] AdaptationsGeorge Balanchine made a ballet to the music, which he originally called Le Palais de Cristal and later simply Symphony in C, first presented by the Paris Opera Ballet in 1947. ReferencesNotes

Bibliography

External links

|