|

Strongly connected component

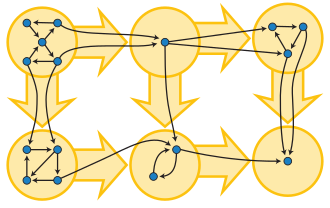

In the mathematical theory of directed graphs, a graph is said to be strongly connected if every vertex is reachable from every other vertex. The strongly connected components of a directed graph form a partition into subgraphs that are themselves strongly connected. It is possible to test the strong connectivity of a graph, or to find its strongly connected components, in linear time (that is, Θ(V + E )). DefinitionsA directed graph is called strongly connected if there is a path in each direction between each pair of vertices of the graph. That is, a path exists from the first vertex in the pair to the second, and another path exists from the second vertex to the first. In a directed graph G that may not itself be strongly connected, a pair of vertices u and v are said to be strongly connected to each other if there is a path in each direction between them. The binary relation of being strongly connected is an equivalence relation, and the induced subgraphs of its equivalence classes are called strongly connected components. Equivalently, a strongly connected component of a directed graph G is a subgraph that is strongly connected, and is maximal with this property: no additional edges or vertices from G can be included in the subgraph without breaking its property of being strongly connected. The collection of strongly connected components forms a partition of the set of vertices of G. A strongly connected component C is called trivial when C consists of a single vertex which is not connected to itself with an edge, and non-trivial otherwise.[1]  If each strongly connected component is contracted to a single vertex, the resulting graph is a directed acyclic graph, the condensation of G. A directed graph is acyclic if and only if it has no strongly connected subgraphs with more than one vertex, because a directed cycle is strongly connected and every non-trivial strongly connected component contains at least one directed cycle. AlgorithmsDFS-based linear-time algorithmsSeveral algorithms based on depth-first search compute strongly connected components in linear time.

Although Kosaraju's algorithm is conceptually simple, Tarjan's and the path-based algorithm require only one depth-first search rather than two. Reachability-based algorithmsPrevious linear-time algorithms are based on depth-first search which is generally considered hard to parallelize. Fleischer et al.[7] in 2000 proposed a divide-and-conquer approach based on reachability queries, and such algorithms are usually called reachability-based SCC algorithms. The idea of this approach is to pick a random pivot vertex and apply forward and backward reachability queries from this vertex. The two queries partition the vertex set into 4 subsets: vertices reached by both, either one, or none of the searches. One can show that a strongly connected component has to be contained in one of the subsets. The vertex subset reached by both searches forms a strongly connected component, and the algorithm then recurses on the other 3 subsets. The expected sequential running time of this algorithm is shown to be O(n log n), a factor of O(log n) more than the classic algorithms. The parallelism comes from: (1) the reachability queries can be parallelized more easily (e.g. by a breadth-first search (BFS), and it can be fast if the diameter of the graph is small); and (2) the independence between the subtasks in the divide-and-conquer process. This algorithm performs well on real-world graphs,[3] but does not have theoretical guarantee on the parallelism (consider if a graph has no edges, the algorithm requires O(n) levels of recursions). Blelloch et al.[8] in 2016 shows that if the reachability queries are applied in a random order, the cost bound of O(n log n) still holds. Furthermore, the queries then can be batched in a prefix-doubling manner (i.e. 1, 2, 4, 8 queries) and run simultaneously in one round. The overall span of this algorithm is log2 n reachability queries, which is probably the optimal parallelism that can be achieved using the reachability-based approach. Generating random strongly connected graphsPeter M. Maurer describes an algorithm for generating random strongly connected graphs,[9] based on a modification of an algorithm for strong connectivity augmentation, the problem of adding as few edges as possible to make a graph strongly connected. When used in conjunction with the Gilbert or Erdős-Rényi models with node relabelling, the algorithm is capable of generating any strongly connected graph on n nodes, without restriction on the kinds of structures that can be generated. ApplicationsAlgorithms for finding strongly connected components may be used to solve 2-satisfiability problems (systems of Boolean variables with constraints on the values of pairs of variables): as Aspvall, Plass & Tarjan (1979) showed, a 2-satisfiability instance is unsatisfiable if and only if there is a variable v such that v and its negation are both contained in the same strongly connected component of the implication graph of the instance.[10] Strongly connected components are also used to compute the Dulmage–Mendelsohn decomposition, a classification of the edges of a bipartite graph, according to whether or not they can be part of a perfect matching in the graph.[11] Related resultsA directed graph is strongly connected if and only if it has an ear decomposition, a partition of the edges into a sequence of directed paths and cycles such that the first subgraph in the sequence is a cycle, and each subsequent subgraph is either a cycle sharing one vertex with previous subgraphs, or a path sharing its two endpoints with previous subgraphs. According to Robbins' theorem, an undirected graph may be oriented in such a way that it becomes strongly connected, if and only if it is 2-edge-connected. One way to prove this result is to find an ear decomposition of the underlying undirected graph and then orient each ear consistently.[12] See alsoReferences

External links

|