|

Spleen

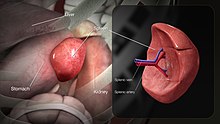

The spleen (from Anglo-Norman espleen, ult. from Ancient Greek σπλήν, splḗn)[1] is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The native Old English word for it is milt, now primarily used for animals; a loanword from Latin is lien. The spleen plays very important roles in regard to red blood cells (erythrocytes) and the immune system.[2] It removes old red blood cells and holds a reserve of blood, which can be valuable in case of hemorrhagic shock, and also recycles iron. As a part of the mononuclear phagocyte system, it metabolizes hemoglobin removed from senescent red blood cells. The globin portion of hemoglobin is degraded to its constitutive amino acids, and the heme portion is metabolized to bilirubin, which is removed in the liver.[3][4] The spleen houses antibody-producing lymphocytes in its white pulp and monocytes which remove antibody-coated bacteria and antibody-coated blood cells by way of blood and lymph node circulation. These monocytes, upon moving to injured tissue (such as the heart after myocardial infarction), turn into dendritic cells and macrophages while promoting tissue healing.[5][6][7] The spleen is a center of activity of the mononuclear phagocyte system and is analogous to a large lymph node, as its absence causes a predisposition to certain infections.[8][4] In humans, the spleen is purple in color and is in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen.[3][9] The surgical process to remove the spleen is known as a splenectomy. StructureIn humans, the spleen is underneath the left part of the diaphragm, and has a smooth, convex surface that faces the diaphragm. It is underneath the ninth, tenth, and eleventh ribs. The other side of the spleen is divided by a ridge into two regions: an anterior gastric portion, and a posterior renal portion. The gastric surface is directed forward, upward, and toward the middle, is broad and concave, and is in contact with the posterior wall of the stomach. Below this it is in contact with the tail of the pancreas. The renal surface is directed medialward and downward. It is somewhat flattened, considerably narrower than the gastric surface, and is in relation with the upper part of the anterior surface of the left kidney and occasionally with the left adrenal gland. There are four ligaments attached to the spleen: gastrosplenic ligament, splenorenal ligament, colicosplenic ligament, and phrenocolic ligament.[10] Measurements

The spleen, in healthy adult humans, is approximately 7 to 14 centimetres (3 to 5+1⁄2 in) in length. An easy way to remember the anatomy of the spleen is the 1×3×5×7×9×10×11 rule. The spleen is 1 by 3 by 5 inches (3 by 8 by 13 cm), weighs approximately 7 oz (200 g), and lies between the ninth and eleventh ribs on the left-hand side and along the axis of the tenth rib. The weight varies between 1 oz (28 g) and 8 oz (230 g) (standard reference range),[12] correlating mainly to height, body weight and degree of acute congestion but not to sex or age.[13]

Blood supply Near the middle of the spleen is a long fissure, the hilum, which is the point of attachment for the gastrosplenic ligament and the point of insertion for the splenic artery and splenic vein. There are other openings present for lymphatic vessels and nerves. In addition to the splenic artery, collateral blood supply is provided by the adjacent short gastric arteries.[14] Like the thymus, the spleen possesses only efferent lymphatic vessels. The spleen is part of the lymphatic system. Both the short gastric arteries and the splenic artery supply it with blood.[15] The germinal centers are supplied by arterioles called penicilliary radicles.[16] Nerve supplyThe spleen is innervated by the splenic plexus, which connects a branch of the celiac ganglia to the vagus nerve. The underlying central nervous processes coordinating the spleen's function seem to be embedded into the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-axis, and the brainstem, especially the subfornical organ.[17] DevelopmentThe spleen is unique in respect to its development within the gut. While most of the gut organs are endodermally derived, the spleen is derived from mesenchymal tissue.[18] Specifically, the spleen forms within, and from, the dorsal mesentery. However, it still shares the same blood supply—the celiac trunk—as the foregut organs. FunctionPulp

OtherOther functions of the spleen are less prominent, especially in the healthy adult:

Clinical significance Enlarged spleenEnlargement of the spleen is known as splenomegaly. It may be caused by sickle cell anemia, sarcoidosis, malaria, bacterial endocarditis, leukemia, polycythemia vera, pernicious anemia, Gaucher's disease, leishmaniasis, Hodgkin's disease, Banti's disease, hereditary spherocytosis, cysts, glandular fever (including mononucleosis or 'Mono' caused by the Epstein–Barr virus and infection from cytomegalovirus), and tumours. Primary tumors of the spleen include hemangiomas and hemangiosarcomas. Marked splenomegaly may result in the spleen occupying a large portion of the left side of the abdomen. The spleen is the largest collection of lymphoid tissue in the body. It is normally palpable in preterm infants, in 30% of normal, full-term neonates, and in 5% to 10% of infants and toddlers. A spleen easily palpable below the costal margin in any child over the age of three to four years should be considered abnormal until proven otherwise. Splenomegaly can result from antigenic stimulation (e.g., infection), obstruction of blood flow (e.g., portal vein obstruction), underlying functional abnormality (e.g., hemolytic anemia), or infiltration (e.g., leukemia or storage disease, such as Gaucher's disease). The most common cause of acute splenomegaly in children is viral infection, which is transient and usually moderate. Basic work-up for acute splenomegaly includes a complete blood count with differential, platelet count, and reticulocyte and atypical lymphocyte counts to exclude hemolytic anemia and leukemia. Assessment of IgM antibodies to viral capsid antigen (a rising titer) is indicated to confirm Epstein–Barr virus or cytomegalovirus. Other infections should be excluded if these tests are negative. Calculators have been developed for measurements of spleen size based on CT, US, and MRI findings.[23] Splenic injuryTrauma, such as a road traffic collision, can cause rupture of the spleen, which is a situation requiring immediate medical attention. AspleniaAsplenia refers to a non-functioning spleen, which may be congenital, or caused by traumatic injury, surgical resection (splenectomy) or a disease such as sickle cell anaemia. Hyposplenia refers to a partially functioning spleen. These conditions may cause[6] a modest increase in circulating white blood cells and platelets, a diminished response to some vaccines, and an increased susceptibility to infection. In particular, there is an increased risk of sepsis from polysaccharide encapsulated bacteria. Encapsulated bacteria inhibit binding of complement or prevent complement assembled on the capsule from interacting with macrophage receptors. Phagocytosis needs natural antibodies, which are immunoglobulins that facilitate phagocytosis either directly or by complement deposition on the capsule. They are produced by IgM memory B cells (a subtype of B cells) in the marginal zone of the spleen.[24][25] A splenectomy (removal of the spleen) results in a greatly diminished frequency of memory B cells.[26] A 28-year follow-up of 740 World War II veterans whose spleens were removed on the battlefield showed a significant increase in the usual death rate from pneumonia (6 rather than the expected 1.3) and an increase in the death rate from ischemic heart disease (41 rather than the expected 30), but not from other conditions.[27] Accessory spleenAn accessory spleen is a small splenic nodule extra to the spleen usually formed in early embryogenesis. Accessory spleens are found in approximately 10 percent of the population[28] and are typically around 1 centimeter in diameter. Splenosis is a condition where displaced pieces of splenic tissue (often following trauma or splenectomy) autotransplant in the abdominal cavity as accessory spleens.[29] Polysplenia is a congenital disease manifested by multiple small accessory spleens,[30] rather than a single, full-sized, normal spleen. Polysplenia sometimes occurs alone, but it is often accompanied by other developmental abnormalities such as intestinal malrotation or biliary atresia, or cardiac abnormalities, such as dextrocardia. These accessory spleens are non-functional. InfarctionSplenic infarction is a condition in which blood flow supply to the spleen is compromised,[31] leading to partial or complete infarction (tissue death due to oxygen shortage) in the organ.[32] Splenic infarction occurs when the splenic artery or one of its branches are occluded, for example by a blood clot. Although it can occur asymptomatically, the typical symptom is severe pain in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, sometimes radiating to the left shoulder. Fever and chills develop in some cases.[33] It has to be differentiated from other causes of acute abdomen. HyaloserositisThe spleen may be affected by hyaloserositis, in which it is coated with fibrous hyaline.[34][35] Society and cultureThere has been a long and varied history of misconceptions regarding the physiological role of the spleen, and it has often been seen as a reservoir for juices closely linked to digestion.[36] In various cultures, the organ has been linked to melancholia, due to the influence of ancient Greek medicine and the associated doctrine of humourism, in which the spleen was believed to be a reservoir for an elusive fluid known as "black bile" (one of the four humours).[36] The spleen also plays an important role in traditional Chinese medicine, where it is considered to be a key organ that displays the Yin aspect of the Earth element (its Yang counterpart is the stomach). In contrast, the Talmud (tractate Berachoth 61b) refers to the spleen as the organ of laughter while possibly suggesting a link with the humoral view of the organ. Etymologically, spleen comes from the Ancient Greek σπλήν (splḗn), where it was the idiomatic equivalent of the heart in modern English. Persius, in his satires, associated spleen with immoderate laughter.[37] In English, William Shakespeare frequently used the word spleen to signify melancholy, but also caprice and merriment.[37] In Julius Caesar, he uses the spleen to describe Cassius's irritable nature:

The spleen, as a byword for melancholy, has also been considered an actual disease.[39] In the early 18th century, the physician Richard Blackmore considered it to be one of the two most prevalent diseases in England (along with consumption).[39] In 1701, Anne Finch (later, Countess of Winchilsea) had published a Pindaric ode, The Spleen, drawing on her first-hand experiences of an affliction which, at the time, also had a reputation of being a fashionably upper-class disease of the English.[40] Both Blackmore and George Cheyne treated this malady as the male equivalent of "the vapours", while preferring the more learned terms "hypochondriasis" and "hysteria".[39][41][42] In the late 18th century, the German word Spleen came to denote eccentric and hypochondriac tendencies that were thought to be characteristic of English people.[37] In French, "splénétique" refers to a state of pensive sadness or melancholy. This usage was popularised by the poems of Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) and his collection Le Spleen de Paris, but it was also present in earlier 19th-century Romantic literature. FoodThe spleen is one of the many organs that may be included in offal. It is not widely eaten as a principal ingredient, but cow spleen sandwiches are eaten in Sicilian cuisine.[43] Chicken spleen is one of the main ingredients of Jerusalem mixed grill.[44] Other animals In cartilaginous and ray-finned fish, the spleen consists primarily of red pulp and is normally somewhat elongated, as it lies inside the serosal lining of the intestine. In many amphibians, especially frogs, it has the more rounded form and there is often a greater quantity of white pulp.[45] In reptiles, birds, and mammals, white pulp is always relatively plentiful, and in birds and some mammals the spleen is typically rounded, but it adjusts its shape somewhat to the arrangement of the surrounding organs. In most vertebrates, the spleen continues to produce red blood cells throughout life; only in mammals this function is lost in middle-aged adults. Many mammals have tiny spleen-like structures known as haemal nodes throughout the body that are presumed to have the same function as the spleen.[45] The spleens of aquatic mammals differ in some ways from those of fully land-dwelling mammals; in general they are bluish in colour. In cetaceans and manatees, they tend to be quite small, but in deep diving pinnipeds, they can be massive, due to their function of storing red blood cells. Marsupials have y-shaped spleens, and it develops postnatally.[46][47][48][49] The only vertebrates lacking a spleen are the lampreys and hagfishes (the early-branching Cyclostomata, or jawless fishes). Even in these animals, there is a diffuse layer of haematopoeitic tissue within the gut wall, which has a similar structure to red pulp and is presumed homologous with the spleen of higher vertebrates.[45] In mice, the spleen stores half the body's monocytes so that, upon injury, they can migrate to the injured tissue and transform into dendritic cells and macrophages to assist wound healing.[5] Additional images

See also

References

External linksLook up spleen in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spleen.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||