|

South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam (RVN; Vietnamese: Việt Nam Cộng hòa; VNCH, French: République du Viêt Nam), was a country in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975, the period when the southern portion of Vietnam was a member of the Western Bloc during part of the Cold War after the 1954 division of Vietnam. It first received international recognition in 1949 as the State of Vietnam within the French Union, with its capital at Saigon (renamed to Ho Chi Minh City in 1976), before becoming a republic in 1955. South Vietnam was bordered by North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, and Thailand across the Gulf of Thailand to the southwest. Its sovereignty was recognized by the United States and 87 other nations, though it failed to gain admission into the United Nations as a result of a Soviet veto in 1957.[2][3] It was succeeded by the Republic of South Vietnam in 1975. In 1976, the Republic of South Vietnam and North Vietnam merged to form the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. The end of the Second World War saw anti-Japanese Việt Minh guerrilla forces, led by communist fighter Ho Chi Minh, proclaiming the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in Hanoi in September 1945.[4] In 1949, during the First Indochina War, the French formed the State of Vietnam, a rival government of anti-communist Vietnamese politicians in Saigon, led by former emperor Bảo Đại. A 1955 referendum on the state's future form of government was widely marred by electoral fraud and resulted in the deposal of Bảo Đại by Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm, who proclaimed himself president of the new republic on 26 October 1955.[5] After the 1954 Geneva Conference, it abandoned its claims to the northern, Việt Minh-controlled part of the country, and established its sovereignty over the southern half of Vietnam consisting of Cochinchina (Nam Kỳ), a former French colony; and parts of Annam (Trung Kỳ), a former French protectorate. Diệm was killed in a CIA-backed military coup led by general Dương Văn Minh in 1963, and a series of short-lived military governments followed. General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu then led the country after a US-encouraged civilian presidential election from 1967 until 1975. The beginnings of the Vietnam War occurred in 1955 with an uprising by the newly organized National Liberation Front for South Vietnam (Việt Cộng), armed and supported by North Vietnam, with backing mainly from China and the Soviet Union. Larger escalation of the insurgency occurred in 1965 with American intervention and the introduction of regular forces of Marines, followed by Army units to supplement the cadre of military advisors guiding the Southern armed forces. A regular bombing campaign over North Vietnam was conducted by offshore US Navy airplanes, warships, and aircraft carriers joined by Air Force squadrons through 1966 and 1967. Fighting peaked up to that point during the Tet Offensive of February 1968, when there were over a million South Vietnamese soldiers and 500,000 US soldiers in South Vietnam. What started as a guerrilla war eventually turned into a more conventional fight as the balance of power became equalized. An even larger, armored invasion from the North commenced during the Easter Offensive following US ground-forces withdrawal, and had nearly overrun some major southern cities until being beaten back. Despite a truce agreement under the Paris Peace Accords, concluded in January 1973 after five years of on-and-off negotiations, fighting continued almost immediately afterwards. The regular North Vietnamese army and Việt-Cộng auxiliaries launched a major second combined-arms conventional invasion in 1975. Communist forces overran Saigon on 30 April 1975, marking the end of the Republic of Vietnam. On 2 July 1976, the North Vietnam-controlled Republic of South Vietnam and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) merged to form the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. EtymologyThe official name of the South Vietnamese state was the "Republic of Vietnam" (Vietnamese: Việt Nam Cộng hòa; French: République du Viêt Nam). The North was known as the "Democratic Republic of Vietnam". Việt Nam (Vietnamese pronunciation: [vjə̀tnam]) was the name adopted by Emperor Gia Long in 1804.[6] It is a variation of "Nam Việt" (南 越, Southern Việt), a name used in ancient times.[6] In 1839, Emperor Minh Mạng renamed the country Đại Nam ("Great South").[7] In 1945, the nation's official name was changed back to "Vietnam". The name is also sometimes rendered as "Viet Nam" in English.[8] The term "South Vietnam" became common usage in 1954, when the Geneva Conference provisionally partitioned Vietnam into communist and capitalist parts. Other names of this state were commonly used during its existence such as Free Vietnam and the Government of Viet Nam (GVN). HistoryFounding of South Vietnam Before World War II, the southern third of Vietnam was the concession (nhượng địa) of Cochinchina, which was administered as part of French Indochina. A French governor-general (toàn quyền) in Hanoi administered all the five parts of Indochina (Tonkin, Annam, Cochinchina, Laos, and Cambodia) while Cochinchina (Nam Kỳ) was under a French governor (thống đốc), but the difference from the other parts with most indigenous intelligentsia and wealthy were naturalized French (Tourane now Đà Nẵng in the central third of Vietnam also enjoyed this privilege because this city was also a concession). The northern third of Vietnam (then the colony (thuộc địa) of Tonkin (Bắc Kỳ) was under a French resident general (thống sứ). Between Tonkin in the north and Cochinchina in the south was the protectorate (xứ bảo hộ) of Annam (Trung Kỳ), under a French resident superior (khâm sứ). A Vietnamese emperor, Bảo Đại, residing in Huế, was the nominal ruler of Annam and Tonkin, which had parallel French and Vietnamese systems of administration, but his influence was less in Tonkin than in Annam. Cochinchina had been annexed by France in 1862 and even elected a deputy to the French National Assembly. It was more "evolved", and French interests were stronger than in other parts of Indochina, notably in the form of French-owned rubber plantations. During World War II, Indochina was administered by Vichy France and occupied by Japan in September 1940. Japanese troops overthrew the Vichy administration on 9 March 1945, Emperor Bảo Đại proclaimed Vietnam independent. When the Japanese surrendered on 16 August 1945, Emperor Bảo Đại abdicated, and Việt Minh leader Hồ Chí Minh proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) in Hanoi and the DRV controlled almost the entire country of Vietnam. In June 1946, France declared Cochinchina a republic, separate from the northern and central parts. A Chinese Kuomintang army arrived to occupy Vietnam's north of the 16th parallel north, while a British-led force occupied the south in September. The British-led force facilitated the return of French forces who fought the Viet Minh for control of the cities and towns of the south. The French Indochina War began on 19 December 1946, with the French regaining control of Hanoi and many other cities. The State of Vietnam was created through co-operation between anti-communist Vietnamese and the French government on 14 June 1949. Former emperor Bảo Đại accepted the position of chief of state (quốc trưởng). This was known as the "Bảo Đại Solution". The colonial struggle in Vietnam became part of the global Cold War. In 1950, China, the Soviet Union and other communist nations recognised the DRV while the United States and other non-communist states recognised the Bảo Đại government. In July 1954, France and the Việt Minh agreed at the Geneva Conference that the Vietnam would be temporarily divided at 17th parallel north and State of Vietnam would rule the territory south of the 17th parallel, pending unification on the basis of supervised elections in 1956. At the time of the conference, it was expected that the South would continue to be a French dependency. However, South Vietnamese Premier Ngô Đình Diệm, who preferred American sponsorship to French, rejected the agreement. When Vietnam was divided, 800,000 to 1 million North Vietnamese, mainly (but not exclusively) Roman Catholics, sailed south as part of Operation Passage to Freedom due to a fear of religious persecution in the North. About 90,000 Việt Minh were evacuated to the North while 5,000 to 10,000 cadre remained in the South, most of them with orders to refocus on political activity and agitation.[9] The Saigon-Cholon Peace Committee, the first Việt Cộng front, was founded in 1954 to provide leadership for this group.[9] Government of Ngô Đình Diệm: 1955–1963 In July 1955, Diệm announced in a broadcast that South Vietnam would not participate in the elections specified in the Geneva Accords.[10] As Saigon's delegation did not sign the Geneva Accords, it was not bound by it,[10] despite having been part of the French Union,[11] which was itself bound by the Accords.[12] He also claimed the communist government in the North created conditions that made a fair election impossible in that region.[13] Dennis J. Duncanson described[undue weight? – discuss] the circumstances prevailing in 1955 and 1956 as "anarchy among sects and of the retiring Việt Minh in the South, the 1956 campaign of terror from Hanoi's land reform and resultant peasant uprising around Vinh in the North".[14] Diệm held a referendum on 23 October 1955 to determine the future of the country. He asked voters to approve a republic, thus removing Bảo Đại as head of state. The poll was supervised by his younger brother, Ngô Đình Nhu. Diệm was credited with 98 percent of the votes. In many districts, there were more votes to remove Bảo Đại than there were registered voters (e.g., in Saigon, 133% of the registered population reportedly voted to remove Bảo Đại). His American advisors had recommended a more modest winning margin of "60 to 70 percent". Diệm, however, viewed the election as a test of authority.[15]: 239 On 26 October 1955, Diệm declared himself the president of the newly proclaimed Republic of Vietnam.[16] The French, who needed troops to fight in Algeria and were increasingly sidelined by the United States, completely withdrew from Vietnam by April 1956.[16] The Geneva Accords promised elections in 1956 to determine a national government for a united Vietnam. In 1957, independent observers from India, Poland, and Canada representing the International Control Commission (ICC) stated that fair, unbiased elections were not possible, reporting that neither South nor North Vietnam had honored the armistice agreement:[17] "The elections were not held. South Vietnam, which had not signed the Geneva Accords, did not believe the Communists in North Vietnam would allow a fair election. In January 1957, the ICC agreed with this perception, reporting that neither South nor North Vietnam had honored the armistice agreement. With the French gone, a return to the traditional power struggle between north and south had begun again." In October 1956 Diệm, with US prodding, launched a land reform program restricting rice farm sizes to a maximum of 247 acres per landowner with the excess land to be sold to landless peasants. More than 1.8m acres of farm land would become available for purchase, the US would pay the landowners and receive payment from the purchasers over a six-year period. Land reform was regarded by the US as a crucial step to build support for the nascent South Vietnamese government and undermine communist propaganda.[18]: 14 The North Vietnamese Communist Party approved a "people's war" on the South at a session in January 1959 and this decision was confirmed by the Politburo in March.[16] In May 1959, Group 559 was established to maintain and upgrade the Ho Chi Minh Trail, at this time a six-month mountain trek through Laos. About 500 of the "regroupees" of 1954 were sent south on the trail during its first year of operation.[19] Diệm attempted to stabilise South Vietnam by defending against Việt Cộng activities. He launched an anti-communist denunciation campaign (Tố Cộng) against the Việt Cộng and military campaigns against three powerful group – the Cao Đài, Hòa Hảo and the Bình Xuyên organised crime syndicate whose military strength combined amounted to approximately 350,000 fighters. By 1960 the land reform process had stalled. Diệm had never truly supported reform because many of his biggest supporters were the country's largest landowners. While the US threatened to cut aid unless land reform and other changes were made, Diệm correctly assessed that the US was bluffing.[18]: 16 Throughout this period, the level of US aid and political support increased. In spite of this, a 1961 US intelligence estimate reported that "one-half of the entire rural region south and southwest of Saigon, as well as some areas to the north, are under considerable Communist control. Some of these areas are in effect denied to all government authority not immediately backed by substantial armed force. The Việt Cộng's strength encircles Saigon and has recently begun to move closer in the city."[20] The report, later excerpted in The Pentagon Papers, continued:

1963–1973 The Diệm government lost support among the populace, and from the Kennedy administration, due to its repression of Buddhists and military defeats by the Việt Cộng. Notably, the Huế Phật Đản shootings of 8 May 1963 led to the Buddhist crisis, provoking widespread protests and civil resistance. The situation came to a head when the Special Forces were sent to raid Buddhist temples across the country, leaving a death toll estimated to be in the hundreds. Diệm was overthrown in a coup on 1 November 1963 with the tacit approval of the US.[citation needed] Diệm's removal and assassination set off a period of political instability and declining legitimacy of the Saigon government. General Dương Văn Minh became president, but he was ousted in January 1964 by General Nguyễn Khánh. Phan Khắc Sửu was named head of state, but power remained with a junta of generals led by Khánh, which soon fell to infighting. Meanwhile, the Gulf of Tonkin incident of 2 August 1964 led to a dramatic increase in direct American participation in the war, with nearly 200,000 troops deployed by the end of the year. Khánh sought to capitalize on the crisis with the Vũng Tàu Charter, a new constitution that would have curtailed civil liberties and concentrated his power, but was forced to back down in the face of widespread protests and strikes. Coup attempts followed in September and February 1965, the latter resulting in Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ becoming prime minister and General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu becoming nominal head of state. Kỳ and Thieu functioned in those roles until 1967, bringing much-desired stability to the government. They imposed censorship and suspended civil liberties, and intensified anticommunist efforts. Under pressure from the US, they held elections for president and the legislature in 1967. The Senate election took place on 2 September 1967. The Presidential election took place on 3 September 1967, Thiệu was elected president with 34% of the vote in a widely criticised poll. The Parliamentary election took place on 22 October 1967. On 31 January 1968, the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and the Việt Cộng broke the traditional truce accompanying the Tết (Lunar New Year) holiday. The Tet Offensive failed to spark a national uprising and was militarily disastrous. By bringing the war to South Vietnam's cities, however, and by demonstrating the continued strength of communist forces, it marked a turning point in US support for the government in South Vietnam. The new administration of Richard Nixon introduced a policy of Vietnamization to reduce US combat involvement and began negotiations with the North Vietnamese to end the war. Thiệu used the aftermath of the Tet Offensive to sideline Kỳ, his chief rival. On 26 March 1970 the government began to implement the Land-to-the-Tiller program of land reform with the US providing US$339m of the program's US$441m cost. Individual landholdings were limited to 15 hectares. US and South Vietnamese forces launched a series of attacks on PAVN/VC bases in Cambodia in April–July 1970. South Vietnam launched an invasion of North Vietnamese bases in Laos in February/March 1971 and were defeated by the PAVN in what was widely regarded as a setback for Vietnamization. Thiệu was reelected unopposed in the Presidential election on 2 October 1971. North Vietnam launched a conventional invasion of South Vietnam in late March 1972 which was only finally repulsed by October with massive US air support. 1973–1975In accordance with the Paris Peace Accords signed on 27 January 1973, US military forces withdrew from South Vietnam at the end of March 1973 while PAVN forces in the South were permitted to remain in place. North Vietnamese leaders had expected that the ceasefire terms would favour their side. As Saigon began to roll back the Việt Cộng, they found it necessary to adopt a new strategy, hammered out at a series of meetings in Hanoi in March 1973, according to the memoirs of Trần Văn Trà. As the Việt Cộng's top commander, Trà participated in several of these meetings. A plan to improve logistics was prepared so that the PAVN would be able to launch a massive invasion of the South, projected for 1976. A gas pipeline would be built from North Vietnam to the Việt Cộng provisional capital in Lộc Ninh, about 60 mi (97 km) north of Saigon. On 15 March 1973, US President Richard Nixon implied that the US would intervene militarily if the communist side violated the ceasefire. Public reaction was unfavorable, and on 4 June 1973 the US Senate passed the Case–Church Amendment to prohibit such intervention. The oil price shock of October 1973 caused significant damage to the South Vietnamese economy. A spokesman for Thiệu admitted in a TV interview that the government was being "overwhelmed" by the inflation caused by the oil shock, while an American businessman living in Saigon stated after the oil shock that attempting to make money in South Vietnam was "like making love to a corpse".[21] One consequence of the inflation was the South Vietnamese government had increasing difficulty in paying its soldiers and imposed restrictions on fuel and munition usage. After two clashes that left 55 South Vietnamese soldiers dead, President Thiệu announced on 4 January 1974 that the war had restarted and that the Paris Peace Accord was no longer in effect. There were over 25,000 South Vietnamese casualties during the ceasefire period.[22] The same month, China attacked South Vietnamese forces in the Paracel Islands, taking control of the islands. In August 1974, Nixon was forced to resign as a result of the Watergate scandal, and the US Congress voted to reduce assistance to South Vietnam from $1 billion a year to $700 million. By this time, the Ho Chi Minh trail, once an arduous mountain trek, had been upgraded into a drivable highway with gasoline stations. In December 1974, the PAVN launched an invasion at Phuoc Long to test the South Vietnamese combat strength and political will and whether the US would respond militarily. With no US military assistance forthcoming, the ARVN were unable to hold and the PAVN successfully captured many of the districts around the provincial capital of Phuoc Long, weakening ARVN resistance in stronghold areas. President Thiệu later abandoned Phuoc Long in early January 1975. As a result, Phuoc Long was the first provincial capital to fall to the PAVN.[23] In 1975, the PAVN launched an offensive at Ban Me Thuot in the Central Highlands, in the first phase of what became known as the Ho Chi Minh Campaign. The South Vietnamese unsuccessfully attempted a defence and counterattack but had few reserve forces, as well as a shortage of spare parts and ammunition. As a consequence, Thiệu ordered a withdrawal of key army units from the Central Highlands, which exacerbated an already perilous military situation and undermined the confidence of the ARVN soldiers in their leadership. The retreat became a rout exacerbated by poor planning and conflicting orders from Thiệu. PAVN forces also attacked south and from sanctuaries in Laos and Cambodia capturing Huế and Da Nang and advanced southwards. As the military situation deteriorated, ARVN troops began deserting. By early April, the PAVN had overrun almost 3/5th of the South. Thiệu requested aid from US President Gerald Ford, but the US Senate would not release extra money to provide aid to South Vietnam, and had already passed laws to prevent further involvement in Vietnam. In desperation, Thiệu recalled Kỳ from retirement as a military commander, but resisted calls to name his old rival prime minister. Fall of Saigon: April 1975 Morale was low in South Vietnam as the PAVN advanced. A last-ditch defense was made by the ARVN 18th Division at the Battle of Xuân Lộc from 9–21 April. Thiệu resigned on 21 April 1975, and fled to Taiwan. He nominated his Vice President Trần Văn Hương as his successor. After only one week in office, the South Vietnamese national assembly voted to hand over the presidency to General Dương Văn Minh. Minh was seen as a more conciliatory figure toward the North, and it was hoped he might be able to negotiate a more favourable settlement to end the war. The North, however, was not interested in negotiations, and its forces captured Saigon. Minh unconditionally surrendered Saigon and the rest of South Vietnam to North Vietnam on 30 April 1975.[24] During the hours leading up to the surrender, the United States undertook a massive evacuation of US government personnel as well as high-ranking members of the ARVN and other South Vietnamese who were seen as potential targets for persecution by the Communists. Many of the evacuees were taken directly by helicopter to multiple aircraft carriers waiting off the coast. Provisional Revolutionary GovernmentFollowing the surrender of Saigon to North Vietnamese forces on 30 April 1975, the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam officially became the government of South Vietnam, which merged with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam to create the Socialist Republic of Vietnam on 2 July 1976.[25] GeographyThe South was divided into coastal lowlands, the mountainous Central Highlands (Cao-nguyen Trung-phan) and the Mekong Delta. South Vietnam's time zone was one hour ahead of North Vietnam, belonging to the UTC+8 time zone with the same time as the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, China, Taiwan] and Western Australia. Apart from the mainland, the Republic of Vietnam also administered parts of the Paracels and Spratly Islands. China seized control of the Paracels in 1974 after the South Vietnamese navy attempted an assault on PRC-claimed islands. Government and politicsSouth Vietnam went through many political changes during its short life. Initially, former Emperor Bảo Đại served as Head of State. He was unpopular however, largely because monarchical leaders were considered collaborators during French rule and because he had spent his reign absent in France. In 1955, Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm held a referendum to decide whether the State of Vietnam would remain a monarchy or become a republic. This referendum was blatantly rigged in favor of a republic. Not only did an implausible 98% vote in favor of deposing Bảo Đại, but over 380,000 more votes were cast than the total number of registered voters; in Saigon, for instance, Diệm was credited with 133% of the vote. Diệm proclaimed himself the president of the newly formed Republic of Vietnam. Despite successes in politics, economics and social change in the first 5 years, Diệm quickly became a dictatorial leader. With the support of the United States government and the CIA, ARVN officers led by General Dương Văn Minh staged a coup and killed him in 1963. The military held a brief interim military government until General Nguyễn Khánh deposed Minh in a January 1964 coup. Until late 1965, multiple coups and changes of government occurred, with some civilians being allowed to give a semblance of civil rule overseen by a military junta. In 1965, the feuding civilian government voluntarily resigned and handed power back to the nation's military, in the hope this would bring stability and unity to the nation. An elected constituent assembly including representatives of all the branches of the military decided to switch the nation's system of government to a semi-presidential system. Military rule initially failed to provide much stability however, as internal conflicts and political inexperience caused various factions of the army to launch coups and counter-coups against one another, making leadership very tumultuous. The situation within the ranks of the military stabilised in mid-1965 when the Republic of Vietnam Air Force chief Nguyễn Cao Kỳ became Prime Minister, with General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu as the figurehead chief of state. As Prime Minister, Kỳ consolidated control of the South Vietnamese government and ruled the country with an iron fist.[26]: 273 In June 1965, Kỳ's influence over the ruling military government was solidified when he forced civilian prime minister Phan Huy Quát from power.[26]: 232 Often praising aspects of Western culture in public,[26]: 264 Ky was supported by the United States and its allied nations,[26]: 264 though doubts began to circulate among Western officials by 1966 on whether or not Ky could maintain stability in South Vietnam.[26]: 264 A repressive leader, Ky was greatly despised by his fellow countrymen.[26]: 273 In early 1966, protesters influenced by popular Buddhist monk Thích Trí Quang attempted an uprising in Quang's hometown of Da Nang.[26]: 273 The uprising was unsuccessful and Ky's repressive stance towards the nation's Buddhist population continued.[26]: 273 In 1967, the unicameral National Assembly was replaced by a bicameral system consisting of a House of Representatives or lower house (Hạ Nghị Viện) and a Senate or upper House (Thượng Nghị Viện) and South Vietnam held its first elections under the new system. The military nominated Nguyễn Văn Thiệu as their candidate, and he was elected with a plurality of the popular vote. Thieu quickly consolidated power much to the dismay of those who hoped for an era of more political openness. He was re-elected unopposed in 1971, receiving a suspiciously high 94% of the vote on an 87% turn-out. Thieu ruled until the final days of the war, resigning on 21 April 1975. Vice-president Trần Văn Hương assumed power for a week, but on 27 April the Parliament and Senate voted to transfer power to Dương Văn Minh who was the nation's last president and who unconditionally surrendered to the Communist forces on 30 April 1975. The National Assembly/House of Representatives was located in the Saigon Opera House, now the Municipal Theatre, Ho Chi Minh City,[27]: 100 while the Senate was located at 45-47 Bến Chương Dương Street (đường Bến Chương Dương), District 1, originally the Chamber of Commerce, and now the Ho Chi Minh City Stock Exchange.[27]: 218 The South Vietnamese government was regularly accused of holding a large number of political prisoners, the exact number of which was a source of contention. Amnesty International, in a report in 1973, estimated the number of South Vietnam's civilian prisoners ranging from 35,257 (as confirmed by Saigon) to 200,000 or more. Among them, approximately 22,000–41,000 were accounted "communist" political prisoners.[28] Leaders

MinistriesSouth Vietnam had the following Ministries:

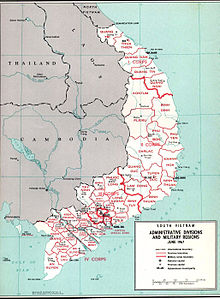

Administrative divisionsProvinces South Vietnam was divided into forty-four provinces: RegionsThroughout its history South Vietnam had many reforms enacted that affected the organisation of its administrative divisions.[31] On 24 October 1956 President Ngô Đình Diệm enacted a reform of the administrative divisions system of the Republic of Vietnam in the form of Decree 147a/NV.[31] This decree divided the region of Trung phần into Trung nguyên Trung phần (the Central Midlands) and Cao nguyên Trung phần (the Central Highlands).[31] The offices of appointed representative and assistant representative of the central government were created for the region of Trung phần, the main representative had an office in Buôn Ma Thuột, while the assistant had an office in Huế.[31] Following the 1963 United States-backed coup d'état that outsted Ngô the Central Government's Representatives in the Trung phần region were gradually replaced by the control of the Tactical zone's Commanders (Tư lệnh Vùng Chiến thuật), which replaced a civil administration with a military one.[31] However, following the 1967 Senate election the military administration was replaced back with civilian administrators.[31] On 1 January 1969, during the presidency of Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, Act 001/69 became effective which abolished the offices of government's representative and assistant government's representative, this was later followed on 12 May 1969 with Decree 544 – NĐ/ThT/QTCS which completely abolished the civil administration in Trung nguyên Trung phần in favour of the Tư lệnh Vùng Chiến thuật.[31] Foreign relations Republic of Vietnam North Vietnam A countries that officially recognizes the Republic of Vietnam Countries that have implicitly recognised the RVN de jure. Countries that have recognised the RVN de facto. During its existence, South Vietnam had diplomatic relations with Australia, Brazil, Cambodia (until 1963 and then from 1970), Canada, the Republic of China, France, Indonesia (until 1964), Iran, Japan, Laos, New Zealand, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, the Republic of Korea, Spain, Thailand, the United Kingdom, the United States, the Vatican and West Germany. Relationship with the United StatesDuring its existence, South Vietnam had a close, strategic alliance with the United States and served as a major counterbalance to communist states like North Vietnam within the Southeast Asian region as a client state of the United States during the Indochina Wars.  The Geneva Accords promised elections in 1956 to determine a national government for a united Vietnam. Neither the United States government nor Ngô Đình Diệm's State of Vietnam signed anything at the 1954 Geneva Conference. With respect to the question of reunification, the non-communist Vietnamese delegation objected strenuously to any division of Vietnam, but lost out when the French accepted the proposal of Viet Minh delegate Phạm Văn Đồng,[33] who proposed that Vietnam eventually be united by elections under the supervision of "local commissions".[34] The United States countered with what became known as the "American Plan", with the support of South Vietnam and the United Kingdom.[35] It provided for unification elections under the supervision of the United Nations, but was rejected by the Soviet delegation and North Vietnamese.[35] U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote in 1954 that "I have never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs who did not agree that had elections been held as of the time of the fighting, possibly eighty percent of the population would have voted for the Communist Ho Chi Minh as their leader rather than Chief of State Bảo Đại. Indeed, the lack of leadership and drive on the part of Bảo Đại was a factor in the feeling prevalent among Vietnamese that they had nothing to fight for."[36] According to the Pentagon Papers, however, from 1954 to 1956 "Ngô Đình Diệm really did accomplish miracles" in South Vietnam:[37] "It is almost certain that by 1956 the proportion which might have voted for Ho—in a free election against Diệm—would have been much smaller than eighty percent."[38] In 1957, independent observers from India, Poland, and Canada representing the International Control Commission (ICC) stated that fair, unbiased elections were not possible, reporting that neither South nor North Vietnam had honored the armistice agreement.[39] The failure to unify the country in 1956 led in 1959 to the foundation of the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (abbreviated NLF but also known as the Việt Cộng), which initiated an organized and widespread guerrilla insurgency against the South Vietnamese government. Hanoi directed the insurgency, which grew in intensity. The United States, under President Eisenhower, initially sent military advisers to train the South Vietnamese Army. As historian James Gibson summed up the situation: "Strategic hamlets had failed…. The South Vietnamese regime was incapable of winning the peasantry because of its class base among landlords. Indeed, there was no longer a 'regime' in the sense of a relatively stable political alliance and functioning bureaucracy. Instead, civil government and military operations had virtually ceased. The National Liberation Front had made great progress and was close to declaring provisional revolutionary governments in large areas."[40] President John F. Kennedy increased the size of the advisory force fourfold and allowed the advisers to participate in combat operations, and later acquiesced in the removal of President Diệm in a military coup. After promising not to do so during the 1964 election campaign, in 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson decided to send in much larger numbers of combat troops, and conflict steadily escalated to become what is commonly known as the Vietnam War. In 1968, the NLF ceased to be an effective fighting organization after the Tet Offensive and the war was largely taken over by regular army units of North Vietnam. Following American withdrawal from the war in 1973, the South Vietnamese government continued fighting the North Vietnamese, until, overwhelmed by a conventional invasion by the North, it finally unconditionally surrendered on 30 April 1975, the day of the surrender of Saigon. North Vietnam controlled South Vietnam under military occupation, while the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam, which had been proclaimed in June 1969 by the NLF, became the nominal government. The North Vietnamese quickly moved to marginalise non-communist members of the PRG and integrate South Vietnam into the communist North. The unified Socialist Republic of Vietnam was inaugurated on 2 July 1976. The Embassy of the Republic of Vietnam in Washington donated 527 reels of South Vietnamese-produced film to the Library of Congress during the embassy's closure following the Fall of Saigon, which are in the Library to this day.[41] International organisationsSouth Vietnam was a member of accT, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the World Bank (IBRD), the International Development Association (IDA), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the IMF, the International Telecommunications Satellite Organization (Intelsat), Interpol, the IOC, the ITU, the League of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (LORCS), UNESCO and the Universal Postal Union (UPU). MilitaryThe Republic of Vietnam Military Forces (RVNMF; Vietnamese: Quân lực Việt Nam Cộng hòa – QLVNCH), was formally established on 30 December 1955.[42] Created out from ex-French Union Army colonial Indochinese auxiliary units (French: Supplétifs), gathered earlier in July 1951 into the French-led Vietnamese National Army – VNA (Vietnamese: Quân Đội Quốc Gia Việt Nam – QĐQGVN), Armée Nationale Vietnamiènne (ANV) in French, the armed forces of the new state consisted in the mid-1950s of ground, air, and naval branches of service, respectively:

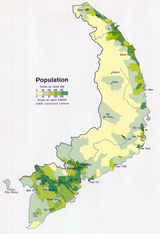

Their roles were defined as follows: to protect the sovereignty of the free Vietnamese nation and that of the Republic; to maintain the political and social order and the rule of law by providing internal security; to defend the newly independent Republic of Vietnam from external (and internal) threats; and ultimately, to help reunify Vietnam. The French ceased training the QLVNCH in 1956 and training passed to American advisers who progressively restructured the military along US military lines.[43]: 254–5 The country was divided from north to south into four corps tactical zones: I Corps, II Corps, III Corps, IV Corps and the Capital Military District in and around Saigon. At the time of signing of the Paris Peace Accords, the South Vietnamese government fielded the fourth largest military force in the world as a result of the American Enhance and Enhance Plus programs with approximately one and one-half million troops in uniform. The lack of sufficient training and dependence on the U.S. for spare parts, fuel, and ammunition caused maintenance and logistical problems. The impact of the 1973 oil crisis, a faltering economy, inflation and reduced US aid led to a steady decline in South Vietnamese military expenditure and effectiveness.[44]: 28 [45]: 83 Economy South Vietnam maintained a capitalist free-market economy with ties to the West. It established an airline named Air Vietnam. The economy was greatly assisted by American aid and the presence of large numbers of Americans in the country between 1961 and 1973 during Vietnam War. Electrical production increased fourteen-fold between 1954 and 1973 while industrial output increase by an average of 6.9 percent annually.[46] During the same period, rice output increased by 203 percent and the number of students in university increased from 2,000 to 90,000.[46] US aid peaked at $2.3 billion in 1973, but dropped to $1.1 billion in 1974.[47] Inflation rose to 200 percent as the country suffered economic shock due to the decrease of American aid as well as the oil price shock of October 1973.[47] The unification of Vietnam in 1976 was followed by the imposition of North Vietnam's centrally planned economy in the South. A 2017 study in the journal Diplomatic History found that South Vietnamese economic planners sought to model the South Vietnamese economy on Taiwan and South Korea, which were perceived as successful examples of how to modernize developing economies.[48] DemographicsIn 1968, the population of South Vietnam was estimated to be 16,259,334. However, about one-fifth of the people who lived in Southern Vietnam (from Quang Tri Province to the South) lived in areas that were controlled by Viet Cong.[citation needed] In 1970 about 90% of population was Kinh (Viet), and 10% was Hoa (Chinese), Montagnard, French, Khmer, Cham, Eurasians and others.[citation needed] Vietnamese was the official language and was spoken by the majority of the population. Despite the end of French colonial rule, the French language maintained a strong presence in South Vietnam where it was used in administration, education (especially at the secondary and higher levels), trade and diplomacy. The ruling elite of South Vietnam spoke French.[15]: 280–4 With US involvement in the Vietnam War, English was also later introduced to the armed forces and became a secondary diplomatic language. Languages spoken by minority groups included Chinese, Khmer, Cham, and other languages spoken by Montagnard groups.[49] Starting from 1955, the South Vietnamese government of Ngô Đình Diệm carried out an assimilation policy towards indigenous peoples (Montagnard) of the Central Highlands and the Cham people, including banning the Cham language in public schools, seizing indigenous lands and granting them to mostly Catholic Northern Kinh people who had moved to South Vietnam during Operation Passage to Freedom.[50] This resulted in increasing nationalism and support for independence among the Cham and other indigenous peoples. Some Cham joined the communist NFL, some others joined the Front de Libération des Hauts Plateaux du Champa. By 1964, civil rights activists and independent organizations of the indigenous peoples, including Cham organizations, had been merged into the Front Unifié de Lutte des Races Opprimées (FULRO), which struggled against both the governments of South Vietnam and the succeeding Socialist Republic of Vietnam until the late 1980s.[51][52] The majority of the population identified as Buddhists. Approximately 10% of the population was Christian, mainly Catholic.[53] Other religions included Caodaism and Hoahaoism. Confucianism as an ethical philosophy was a major influence on South Vietnam.[54][55] CultureCultural life was strongly influenced by China until French domination in the 18th century. At that time, the traditional culture began to acquire an overlay of Western characteristics. Many families had three generations living under one roof. The emerging South Vietnamese middle class and youth in the 1960s became increasingly more Westernised, and followed American cultural and social trends, especially in music, fashion and social attitudes in major cities like Saigon. Media

Radio There were four AM and one FM radio stations, all of them owned by the government (VTVN), named Radio Vietnam. One of them was designated as a nationwide civilian broadcast, another was for military service and the other two stations included a French-language broadcast station and foreign language station broadcasting in Chinese, English, Khmer and Thai. Radio Vietnam started its operation in 1955 under then President Ngo Dinh Diem, and ceased operation on 30 April 1975, with the broadcast of surrender by Duong Van Minh. The radio stations across the former South were later reused by the communist regime to broadcast their state-run radio service. TelevisionTelevision was introduced to South Vietnam on 7 February 1966 with a black-and-white FCC system. Covering major cities in South Vietnam, started with a one-hour broadcast per day then increased to six hours in the evening during the 1970s. There were two main channels:

Both channels used an airborne transmission relay system from airplanes flying at high altitudes, called Stratovision. See alsoNotes

References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to South Vietnam. Wikiquote has quotations related to South Vietnam.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||