|

Social metabolism

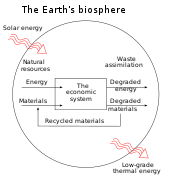

Social metabolism or socioeconomic metabolism is the set of flows of materials and energy that occur between nature and society, between different societies, and within societies. These human-controlled material and energy flows are a basic feature of all societies but their magnitude and diversity largely depend on specific cultures, or sociometabolic regimes.[1][2] Social or socioeconomic metabolism is also described as "the self-reproduction and evolution of the biophysical structures of human society. It comprises those biophysical transformation processes, distribution processes, and flows, which are controlled by humans for their purposes. The biophysical structures of society (‘in use stocks’) and socioeconomic metabolism together form the biophysical basis of society."[3] Social metabolic processes begin with the human appropriation of materials and energy from nature. These can be transformed and circulated to be consumed and excreted finally back to nature itself. Each of these processes has a different environmental impact depending on how it is performed, the amount of materials and energy involved in the process, the area where it occurs, the time available or nature's regenerative capacity.[1][2] Social metabolism represents an extension of the metabolism concept from biological organisms like human bodies to the biophysical basis of society. In capitalist societies, humans build and operate mines and farms, oil refineries and power stations, factories and infrastructure to supply the energy and material flows needed for the physical reproduction of a specific culture. In-use stocks, which comprise buildings, vehicles, appliances, infrastructure, etc., are built up and maintained by the different industrial processes that are part of social metabolism. These stocks then provide services to people in the form of shelter, transportation, or communication. Karl Marx understood these aspects of the specifically capitalist mode of production to be alienated, as they reflect a socially and economically mediated form of social metabolism, reducing the amount of energy regenerated for both the human beings involved and their natural environment, only to displace it to the interests of capital. John Bellamy Foster has thus developed the concept of metabolic rift to develop Marx's understanding of the deleterious effect of capitalism on ecosystems. Society and its metabolism together form an autopoietic system, a complex system that reproduces itself. Neither culture nor social metabolism can reproduce themselves in isolation. Humans need food and shelter, which is delivered by social metabolism, and the latter needs humans to operate it. Social or socioeconomic metabolism stipulates that human society and its interaction with nature form a complex self-reproducing system, and it can therefore be seen as paradigm for studying the biophysical basis of human societies under the aspect of self-reproduction. "A common paradigm can facilitate model combination and integration, which can lead to more robust and comprehensive interdisciplinary assessments of sustainable development strategies. ... The use of social or socioeconomic metabolism as paradigm can help to justify alternative economic concepts."[3] Origins of the conceptThe concept of social metabolism emerged in the nineteenth century, which was a time of scientific integration and reciprocity among naturalists and social scholars. The evolutionary perspective, particularly analogical reasoning, provided crossties between natural and social sciences.[4] It was only in the late 1970s that the human exceptionalism paradigm was rigorously questioned, leading to the birth of environmental sociology.[4] Social metabolism as a proxy for human developmentThe concept of social metabolism has been used in historical research as a framework to describe the development of human societies over time. Particularly important in this field is the work done by the German historian Rolf Sieferle on the socio-ecological patterns of societies. Focusing on the energy dimension of social metabolism (i.e. the energetic metabolism), Sieferle suggested that it is possible to classify different "socio-ecological patterns", or regimes, of human societies over time, according to the main source of energy and the dominant energy conversion technology that these use. Sieferle identified three main regimes that characterised human history: hunting-gathering, agrarian and industrial. The hunting-gathering regime relied on "passive solar energy utilization", as in this configuration humans relied mainly on products of recent photosynthesis, namely plants and animals for food and firewood for heat. This resulted in highly nomadic societies and low population density. Eventually, the Neolithic Revolution allowed societies to switch to an agrarian regime based on "active solar energy utilization". Humans started to modify their environment more systematically through deforestation in order maximise the exploitation of land and sun for farming to produce food for humans and for livestock. This led to sedentary societies, increased human labour burden and to higher population growth, which in turn boosted the development of more structured social hierarchies and dynamics. Finally, the invention of the steam engine in the 16th century triggered the emergence of the industrial regime, that relies on fossil fuels as its main energy source. This led to the industrial socio-ecological pattern that regulates human society as we now it today. Following Sieferle's footsteps, other social scientists eventually tried to reconstruct human history through social metabolism, also through quantitative analyses and indicators. Among them it is worth mentioning the Total Primary Energy Supply (TPES), the Domestic Energy Consumption (DEC), the Human Appropriation of Net Primary Production (HANPP) and others. Using energetic metabolism as a proxy for human development has important implications not only for historical analysis, but also for the elaboration of future scenarios. According to many studies, peak fossil fuel (i.e. the maximum rate of fossil fuels extraction on a global scale) has already been reached or is likely to be reached soon. Understanding what will be the next main energy source and conversion technology of human societies in the future has important policy and societal implications. Accounting methodsStudies of social metabolism can be carried out at different levels of system aggregation, see material flow analysis. In material flow accounting, for example, the inputs and outputs of materials and energy of a particular state or region, as well as imports and exports, are analysed. Such studies are facilitated by the ease of access to information about commercial transactions.[5][6] There are different schools of thought concerning social metabolism, each with its own accounting method. The two that can be identified have their roots in two different schools of research, the Material and Energy Flow Analyses (MEFA) which is related to the "Vienna School", not to be confused with the Austrian School, and the Multi-Scale Integrated Analysis of Societal and Ecosystem Metabolism (MuSIASEM), which finds its roots in the "Barcelona school", connected to the Autonomous University of Barcelona. The scholar who laid the foundations for MEFA is Marina Fischer-Kowalski, while MuSIASEM developed around Mario Giampietro and Kozo Mayumi.[7] While MEFA, primarily focusses its research on national economies across time and space, MuSIASEM primarily focusses its research on contemporary economies, herein they focus on specific subsectors of the economy.[7]: 190 This brings with it some methodological differences as well, in the MEFA school of thought, researchers have been more geared toward standardizing data collection as much as possible, which would result in an easier comparison between a wide range of cases and data. On the other hand, in the MuSIASEM school, scholars have been more reluctant to do this, they prefer to have a tailor-made form of accounting for every case, operating within a predetermined 'grammar'.[7]: 191 See also

References

|