|

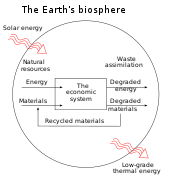

Market failure In neoclassical economics, market failure is a situation in which the allocation of goods and services by a free market is not Pareto efficient, often leading to a net loss of economic value.[1][2][3] The first known use of the term by economists was in 1958,[4] but the concept has been traced back to the Victorian philosopher Henry Sidgwick.[5] Market failures are often associated with public goods,[6] time-inconsistent preferences,[7] information asymmetries,[8] non-competitive markets, principal–agent problems, or externalities.[9] The existence of a market failure is often the reason that self-regulatory organizations, governments or supra-national institutions intervene in a particular market.[10][11] Economists, especially microeconomists, are often concerned with the causes of market failure and possible means of correction.[12] Such analysis plays an important role in many types of public policy decisions and studies. However, government policy interventions, such as taxes, subsidies, wage and price controls, and regulations, may also lead to an inefficient allocation of resources, sometimes called government failure.[13] Most mainstream economists believe that there are circumstances (like building codes, fire safety regulations or endangered species laws) in which it is possible for government or other organizations to improve the inefficient market outcome. Several heterodox schools of thought disagree with this as a matter of ideology.[14][15] An ecological market failure exists when human activity in a market economy is exhausting critical non-renewable resources, disrupting fragile ecosystems, or overloading biospheric waste absorption capacities. In none of these cases does the criterion of Pareto efficiency obtain.[16] CategoriesDifferent economists have different views about what events are the sources of market failure. Mainstream economic analysis widely accepts that a market failure (relative to Pareto efficiency) can occur for three main reasons: if the market is "monopolised" or a small group of businesses hold significant market power, if production of the good or service results in an externality (external costs or benefits), or if the good or service is a "public good". Nature of the marketAgents in a market can gain market power, allowing them to block other mutually beneficial gains from trade from occurring. This can lead to inefficiency due to imperfect competition, which can take many different forms, such as monopolies,[17] monopsonies, or monopolistic competition, if the agent does not implement perfect price discrimination.  It is then a further question about what circumstances allow a monopoly to arise. In some cases, monopolies can maintain themselves where there are "barriers to entry" that prevent other companies from effectively entering and competing in an industry or market. Or there could exist significant first-mover advantages in the market that make it difficult for other firms to compete. Moreover, monopoly can be a result of geographical conditions created by huge distances or isolated locations. This leads to a situation where there are only few communities scattered across a vast territory with only one supplier. Australia is an example that meets this description.[18] A natural monopoly is a firm whose per-unit cost decreases as it increases output; in this situation it is most efficient (from a cost perspective) to have only a single producer of a good. Natural monopolies display so-called increasing returns to scale. It means that at all possible outputs marginal cost needs to be below average cost if average cost is declining. One of the reasons is the existence of fixed costs, which must be paid without considering the amount of output, what results in a state where costs are evenly divided over more units leading to the reduction of cost per unit.[19] Nature of the goodsNon-excludabilitySome markets can fail due to the nature of the goods being exchanged. For instance, some goods can display the attributes of public goods[17] or common goods,[20] wherein sellers are unable to exclude non-buyers from using a product, as in the development of inventions that may spread freely once revealed, such as developing a new method of harvesting. This can cause underinvestment because developers cannot capture enough of the benefits from success to make the development effort worthwhile. This can also lead to resource depletion in the case of common-pool resources, whereby the use of the resource is rival but non-excludable, there is no incentive for users to conserve the resource. An example of this is a lake with a natural supply of fish: if people catch the fish faster than the fish can reproduce, then the fish population will dwindle until there are no fish left for future generations. ExternalitiesA good or service could also have significant externalities,[9][17] where gains or losses associated with the product, production or consumption of a product, differ from the private cost. These gains or losses are imposed on a third-party that did not take part in the original market transaction. These externalities can be innate to the methods of production or other conditions important to the market.[3] "The Problem of Social Cost" illuminates a different path towards social optimum showing the Pigouvian tax is not the only way towards solving externalities. It is hard to say who discovered externalities first since many classical economists saw the importance of education or a lighthouse, but it was Alfred Marshall who wanted to explore this more. He wondered why long-run supply curve under perfect competition could be decreasing so he founded "external economies" ([21][22]). Externalities can be positive or negative depending on how a good/service is produced or what the good/service provides to the public. Positive externalities tend to be goods like vaccines, schools, or advancement of technology. They usually provide the public with a positive gain. Negative externalities would be like noise or air pollution. Coase shows this with his example of the case Sturges v. Bridgman it involved a confectioner and doctor. The confectioner had lived there many years and soon the doctor several years into residency decides to build a consulting room; it is right by the confectioner's kitchen which releases vibrations from his grinding of pestle and mortar ([23][24] ). The doctor wins the case by a claim of nuisance so the confectioner would have to cease from using his machine. Coase argues there could have been bargains instead the confectioner could have paid the doctor to continue the source of income from using the machine hopefully it is more than what the Doctor is losing ([25][26] ). Vice versa the doctor could have paid the confectioner to cease production since he is prohibiting a source of income from the confectioner. Coase used a few more examples similar in scope dealing with social cost of an externality and the possible resolutions.  Traffic congestion is an example of market failure that incorporates both non-excludability and externality. Public roads are common resources that are available for the entire population's use (non-excludable), and act as a complement to cars (the more roads there are, the more useful cars become). Because there is very low cost but high benefit to individual drivers in using the roads, the roads become congested, decreasing their usefulness to society. Furthermore, driving can impose hidden costs on society through pollution (externality). Solutions for this include public transportation, congestion pricing, tolls, and other ways of making the driver include the social cost in the decision to drive.[3] Perhaps the best example of the inefficiency associated with common/public goods and externalities is the environmental harm caused by pollution and overexploitation of natural resources.[3] Nature of the exchangeSome markets can fail due to the nature of their exchange. Markets may have significant transaction costs, agency problems, or informational asymmetry.[3][17] Such incomplete markets may result in economic inefficiency, but also have a possibility of improving efficiency through market, legal, and regulatory remedies. From contract theory, decisions in transactions where one party has more or better information than the other is considered "asymmetry". This creates an imbalance of power in transactions which can sometimes cause the transactions to go awry. Examples of this problem are adverse selection[28] and moral hazard. Most commonly, information asymmetries are studied in the context of principal–agent problems. George Akerlof, Michael Spence, and Joseph E. Stiglitz developed the idea and shared the 2001 Nobel Prize in Economics.[29] Bounded rationalityIn Models of Man, Herbert A. Simon points out that most people are only partly rational, and are emotional/irrational in the remaining part of their actions. In another work, he states "boundedly rational agents experience limits in formulating and solving complex problems and in processing (receiving, storing, retrieving, transmitting) information" (Williamson, p. 553, citing Simon). Simon describes a number of dimensions along which "classical" models of rationality can be made somewhat more realistic, while sticking within the vein of fairly rigorous formalization. These include:

Simon suggests that economic agents employ the use of heuristics to make decisions rather than a strict rigid rule of optimization. They do this because of the complexity of the situation, and their inability to process and compute the expected utility of every alternative action. Deliberation costs might be high and there are often other, concurrent economic activities also requiring decisions. Coase theoremThe Coase theorem, developed by Ronald Coase and labeled as such by George Stigler, states that private transactions are efficient as long as property rights exist, only a small number of parties are involved, and transactions costs are low. Additionally, this efficiency will take place regardless of who owns the property rights. This theory comes from a section of Coase's Nobel prize-winning work The Problem of Social Cost. While the assumptions of low transactions costs and a small number of parties involved may not always be applicable in real-world markets, Coase's work changed the long-held belief that the owner of property rights was a major determining factor in whether or not a market would fail.[30] The Coase theorem points out when one would expect the market to function properly even when there are externalities.

As a result, agents' control over the uses of their goods and services can be imperfect, because the system of rights which defines that control is incomplete. Typically, this falls into two generalized rights – excludability and transferability. Excludability deals with the ability of agents to control who uses their commodity, and for how long – and the related costs associated with doing so. Transferability reflects the right of agents to transfer the rights of use from one agent to another, for instance by selling or leasing a commodity, and the costs associated with doing so. If a given system of rights does not fully guarantee these at minimal (or no) cost, then the resulting distribution can be inefficient.[11] Considerations such as these form an important part of the work of institutional economics.[31] Nonetheless, views still differ on whether something displaying these attributes is meaningful without the information provided by the market price system.[32] Business cyclesMacroeconomic business cycles are a part of the market. They are characterized by constant downswings and upswings which influence economic activity. Therefore, this situation requires some kind of government intervention.[18] Interpretations and policy examplesThe above causes represent the mainstream view of what market failures mean and of their importance in the economy. This analysis follows the lead of the neoclassical school, and relies on the notion of Pareto efficiency,[33] which can be in the "public interest", as well as in interests of stakeholders with equity.[12] This form of analysis has also been adopted by the Keynesian or new Keynesian schools in modern macroeconomics, applying it to Walrasian models of general equilibrium in order to deal with failures to attain full employment, or the non-adjustment of prices and wages. Policies to prevent market failure are already commonly implemented in the economy. For example, to prevent information asymmetry, members of the New York Stock Exchange agree to abide by its rules in order to promote a fair and orderly market in the trading of listed securities. The members of the NYSE presumably believe that each member is individually better off if every member adheres to its rules – even if they have to forego money-making opportunities that would violate those rules. A simple example of policies to address market power is government antitrust policies. As an additional example of externalities, municipal governments enforce building codes and license tradesmen to mitigate the incentive to use cheaper (but more dangerous) construction practices, ensuring that the total cost of new construction includes the (otherwise external) cost of preventing future tragedies. The voters who elect municipal officials presumably feel that they are individually better off if everyone complies with the local codes, even if those codes may increase the cost of construction in their communities. CITES is an international treaty to protect the world's common interest in preserving endangered species – a classic "public good" – against the private interests of poachers, developers and other market participants who might otherwise reap monetary benefits without bearing the known and unknown costs that extinction could create. Even without knowing the true cost of extinction, the signatory countries believe that the societal costs far outweigh the possible private gains that they have agreed to forego. Some remedies for market failure can resemble other market failures. For example, the issue of systematic underinvestment in research is addressed by the patent system that creates artificial monopolies for successful inventions. ObjectionsPublic choiceEconomists such as Milton Friedman from the Chicago school and others from the Public Choice school, argue[citation needed] that market failure does not necessarily imply that the government should attempt to solve market failures, because the costs of government failure might be worse than those of the market failure it attempts to fix. This failure of government is seen as the result of the inherent problems of democracy and other forms of government perceived by this school and also of the power of special-interest groups (rent seekers) both in the private sector and in the government bureaucracy. Conditions that many would regard as negative are often seen as an effect of subversion of the free market by coercive government intervention. Beyond philosophical objections, a further issue is the practical difficulty that any single decision maker may face in trying to understand (and perhaps predict) the numerous interactions that occur between producers and consumers in any market. AustrianSome advocates of laissez-faire capitalism, including many economists of the Austrian School, argue that there is no such phenomenon as "market failure". Israel Kirzner states that, "Efficiency for a social system means the efficiency with which it permits its individual members to achieve their individual goals."[34] Inefficiency only arises when means are chosen by individuals that are inconsistent with their desired goals.[35] This definition of efficiency differs from that of Pareto efficiency, and forms the basis of the theoretical argument against the existence of market failures. However, providing that the conditions of the first welfare theorem are met, these two definitions agree, and give identical results. Austrians argue that the market tends to eliminate its inefficiencies through the process of entrepreneurship driven by the profit motive; something the government has great difficulty detecting, or correcting.[36] MarxianObjections also exist on more fundamental bases, such as Marxian analysis. Colloquial uses of the term "market failure" reflect the notion of a market "failing" to provide some desired attribute different from efficiency – for instance, high levels of inequality can be considered a "market failure", yet are not Pareto inefficient, and so would not be considered a market failure by mainstream economics.[3] In addition, many Marxian economists would argue that the system of private property rights is a fundamental problem in itself, and that resources should be allocated in another way entirely. This is different from concepts of "market failure" which focuses on specific situations – typically seen as "abnormal" – where markets have inefficient outcomes. Marxists, in contrast, would say that markets have inefficient and democratically unwanted outcomes – viewing market failure as an inherent feature of any capitalist economy – and typically omit it from discussion, preferring to ration finite goods not exclusively through a price mechanism, but based upon need as determined by society expressed through the community. Ecological

In ecological economics, the concept of externalities is considered a misnomer, since market agents are viewed as making their incomes and profits by systematically 'shifting' the social and ecological costs of their activities onto other agents, including future generations. Hence, externalities is a modus operandi of the market, not a failure: The market cannot exist without constantly 'failing'. The fair and even allocation of non-renewable resources over time is a market failure issue of concern to ecological economics. This issue is also known as 'intergenerational fairness'. It is argued that the market mechanism fails when it comes to allocating the Earth's finite mineral stock fairly and evenly among present and future generations, as future generations are not, and cannot be, present on today's market.[37]: 375 [38]: 142f In effect, today's market prices do not, and cannot, reflect the preferences of the yet unborn.[39]: 156–160 This is an instance of a market failure passed unrecognized by most mainstream economists, as the concept of Pareto efficiency is entirely static (timeless).[40]: 181f Imposing government restrictions on the general level of activity in the economy may be the only way of bringing about a more fair and even intergenerational allocation of the mineral stock. Hence, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen and Herman Daly, the two leading theorists in the field, have both called for the imposition of such restrictions: Georgescu-Roegen has proposed a minimal bioeconomic program, and Daly has proposed a comprehensive steady-state economy.[37]: 374–379 [40] However, Georgescu-Roegen, Daly, and other economists in the field agree that on a finite Earth, geologic limits will inevitably strain most fairness in the longer run, regardless of any present government restrictions: Any rate of extraction and use of the finite stock of non-renewable mineral resources will diminish the remaining stock left over for future generations to use.[37]: 366–369 [41]: 369–371 [42]: 165–167 [43]: 270 [44]: 37 Another ecological market failure is presented by the overutilisation of an otherwise renewable resource at a point in time, or within a short period of time. Such overutilisation usually occurs when the resource in question has poorly defined (or non-existing) property rights attached to it while too many market agents engage in activity simultaneously for the resource to be able to sustain it all. Examples range from over-fishing of fisheries and over-grazing of pastures to over-crowding of recreational areas in congested cities. This type of ecological market failure is generally known as the 'tragedy of the commons'. In this type of market failure, the principle of Pareto efficiency is violated the utmost, as all agents in the market are left worse off, while nobody are benefitting. It has been argued that the best way to remedy a 'tragedy of the commons'-type of ecological market failure is to establish enforceable property rights politically – only, this may be easier said than done.[16]: 172f The issue of climate change presents an overwhelming example of a 'tragedy of the commons'-type of ecological market failure: The Earth's atmosphere may be regarded as a 'global common' exhibiting poorly defined (non-existing) property rights, and the waste absorption capacity of the atmosphere with regard to carbon dioxide is presently being heavily overloaded by a large volume of emissions from the world economy.[45]: 347f Historically, the fossil fuel dependence of the Industrial Revolution has unintentionally thrown mankind out of ecological equilibrium with the rest of the Earth's biosphere (including the atmosphere), and the market has failed to correct the situation ever since. Quite the opposite: The unrestricted market has been exacerbating this global state of ecological dis-equilibrium, and is expected to continue doing so well into the foreseeable future.[46]: 95–101 This particular market failure may be remedied to some extent at the political level by the establishment of an international (or regional) cap and trade property rights system, where carbon dioxide emission permits are bought and sold among market agents.[16]: 433–35 The term 'uneconomic growth' describes a pervasive ecological market failure: The ecological costs of further economic growth in a so-called 'full-world economy' like the present world economy may exceed the immediate social benefits derived from this growth.[16]: 16–21 Zerbe and McCurdyZerbe and McCurdy connected criticism of market failure paradigm to transaction costs. Market failure paradigm is defined as follows: "A fundamental problem with the concept of market failure, as economists occasionally recognize, is that it describes a situation that exists everywhere." Transaction costs are part of each market exchange, although the price of transaction costs is not usually determined. They occur everywhere and are unpriced. Consequently, market failures and externalities can arise in the economy every time transaction costs arise. There is no place for government intervention. Instead, government should focus on the elimination of both transaction costs and costs of provision.[47] See also

References

Further reading

External links

|