|

Productivity

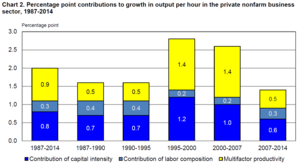

Productivity is the efficiency of production of goods or services expressed by some measure. Measurements of productivity are often expressed as a ratio of an aggregate output to a single input or an aggregate input used in a production process, i.e. output per unit of input, typically over a specific period of time.[1] The most common example is the (aggregate) labour productivity measure, one example of which is GDP per worker. There are many different definitions of productivity (including those that are not defined as ratios of output to input) and the choice among them depends on the purpose of the productivity measurement and data availability. The key source of difference between various productivity measures is also usually related (directly or indirectly) to how the outputs and the inputs are aggregated to obtain such a ratio-type measure of productivity.[2] Productivity is a crucial factor in the production performance of firms and nations. Increasing national productivity can raise living standards because increase in income per capita improves people's ability to purchase goods and services, enjoy leisure, improve housing, and education and contribute to social and environmental programs. Productivity growth can also help businesses to be more profitable.[3] Partial productivityProductivity measures that use one class of inputs or factors, but not multiple factors, are called partial productivities.[4] In practice, measurement in production means measures of partial productivity. Interpreted correctly, these components are indicative of productivity development, and approximate the efficiency with which inputs are used in an economy to produce goods and services. However, productivity is only measured partially – or approximately. In a way, the measurements are defective because they do not measure everything, but it is possible to interpret correctly the results of partial productivity and to benefit from them in practical situations. At the company level, typical partial productivity measures are such things as worker hours, materials or energy used per unit of production.[4] Before the widespread use of computer networks, partial productivity was tracked in tabular form and with hand-drawn graphs. Tabulating machines for data processing began being widely used in the 1920s and 1930s and remained in use until mainframe computers became widespread in the late 1960s through the 1970s. By the late 1970s inexpensive computers allowed industrial operations to perform process control and track productivity. Today data collection is largely computerized and almost any variable can be viewed graphically in real time or retrieved for selected time periods. Labour productivity  In macroeconomics, a common partial productivity measure is labour productivity. Labour productivity is a revealing indicator of several economic indicators as it offers a dynamic measure of economic growth, competitiveness, and living standards within an economy.[citation needed] It is the measure of labour productivity (and all that this measure takes into account) which helps explain the principal economic foundations that are necessary for both economic growth and social development. In general labour productivity is equal to the ratio between a measure of output volume (gross domestic product or gross value added) and a measure of input use (the total number of hours worked or total employment).[citation needed] The output measure is typically net output, more specifically the value added by the process under consideration, i.e. the value of outputs minus the value of intermediate inputs. This is done in order to avoid double-counting when an output of one firm is used as an input by another in the same measurement.[5] In macroeconomics the most well-known and used measure of value-added is the gross domestic product or GDP. Increases in it are widely used as a measure of the economic growth of nations and industries. GDP is the income available for paying capital costs, labor compensation, taxes and profits.[6] Some economists instead use gross value added (GVA); there is normally a strong correlation between GDP and GVA.[7] The measure of input use reflects the time, effort and skills of the workforce. The denominator of the ratio of labour productivity, the input measure is the most important factor that influences the measure of labour productivity. Labour input is measured either by the total number of hours worked of all persons employed or total employment (head count).[7] There are both advantages and disadvantages associated with the different input measures that are used in the calculation of labour productivity. It is generally accepted that the total number of hours worked is the most appropriate measure of labour input because a simple headcount of employed persons can hide changes in average hours worked and has difficulties accounting for variations in work such as a part-time contract, paid leave, overtime, or shifts in normal hours. However, the quality of hours-worked estimates is not always clear. In particular, statistical establishment and household surveys are difficult to use because of their varying quality of hours-worked estimates and their varying degree of international comparability. GDP per capita is a rough measure of average living standards or economic well-being and is one of the core indicators of economic performance.[8] GDP is, for this purpose, only a very rough measure. Maximizing GDP, in principle, also allows maximizing capital usage. For this reason, GDP is systematically biased in favour of capital intensive production at the expense of knowledge and labour-intensive production. The use of capital in the GDP-measure is considered to be as valuable as the production's ability to pay taxes, profits and labor compensation. The bias of the GDP is actually the difference between the GDP and the producer income.[9] Another labour productivity measure, output per worker, is often seen as a proper measure of labour productivity, as here: "Productivity isn't everything, but in the long run it is almost everything. A country's ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker."[10] This measure (output per worker) is, however, more problematic than the GDP or even invalid because this measure allows maximizing all supplied inputs, i.e. materials, services, energy and capital at the expense of producer income.[citation needed] Multi-factor productivity When multiple inputs are considered, the measure is called multi-factor productivity or MFP.[5] Multi-factor productivity is typically estimated using growth accounting. If the inputs specifically are labor and capital, and the outputs are value added intermediate outputs, the measure is called total factor productivity (TFP].[11] TFP measures the residual growth that cannot be explained by the rate of change in the services of labour and capital. MFP replaced the term TFP used in the earlier literature, and both terms continue in use (usually interchangeably).[12] TFP is often interpreted as a rough average measure of productivity, more specifically the contribution to economic growth made by factors such as technical and organisational innovation.[6] The most famous description is that of Robert Solow's (1957): "I am using the phrase 'technical change' as a shorthand expression for any kind of shift in the production function. Thus slowdowns, speed ups, improvements in the education of the labor force and all sorts of things will appear as 'technical change' ." The original MFP model[13] involves several assumptions: that there is a stable functional relation between inputs and output at the economy-wide level of aggregation, that this function has neoclassical smoothness and curvature properties, that inputs are paid the value of their marginal product, that the function exhibits constant returns to scale, and that technical change has the Hicks’n neutral form.[14] In practice, TFP is "a measure of our ignorance", as Abramovitz (1956) put it, precisely because it is a residual. This ignorance covers many components, some wanted (like the effects of technical and organizational innovation), others unwanted (measurement error, omitted variables, aggregation bias, model misspecification)[15] Hence the relationship between TFP and productivity remains unclear.[2] Total productivityWhen all outputs and inputs are included in the productivity measure it is called total productivity. A valid measurement of total productivity necessitates considering all production inputs. If we omit an input in productivity (or income accounting) this means that the omitted input can be used unlimitedly in production without any impact on accounting results. Because total productivity includes all production inputs, it is used as an integrated variable when we want to explain income formation of the production process. Davis has considered[16] the phenomenon of productivity, measurement of productivity, distribution of productivity gains, and how to measure such gains. He refers to an article[17] suggesting that the measurement of productivity shall be developed so that it "will indicate increases or decreases in the productivity of the company and also the distribution of the ’fruits of production’ among all parties at interest". According to Davis, the price system is a mechanism through which productivity gains are distributed, and besides the business enterprise, receiving parties may consist of its customers, staff and the suppliers of production inputs. In the main article is presented the role of total productivity as a variable when explaining how income formation of production is always a balance between income generation and income distribution. The income change created by production function is always distributed to the stakeholders as economic values within the review period. Benefits of productivity growth Productivity growth is a crucial source of growth in living standards. Productivity growth means more value is added in production and this means more income is available to be distributed. At a firm or industry level, the benefits of productivity growth can be distributed in a number of different ways:

Productivity growth is important to the firm because it means that it can meet its (perhaps growing) obligations to workers, shareholders, and governments (taxes and regulation), and still remain competitive or even improve its competitiveness in the market place. Adding more inputs will not increase the income earned per unit of input (unless there are increasing returns to scale). In fact, it is likely to mean lower average wages and lower rates of profit. But, when there is productivity growth, even the existing commitment of resources generates more output and income. Income generated per unit of input increases. Additional resources are also attracted into production and can be profitably employed. Drivers of productivity growthIn the most immediate sense, productivity is determined by the available technology or know-how for converting resources into outputs, and the way in which resources are organized to produce goods and services. Historically, productivity has improved through evolution as processes with poor productivity performance are abandoned and newer forms are exploited. Process improvements may include organizational structures (e.g. core functions and supplier relationships), management systems, work arrangements, manufacturing techniques, and changing market structure. A famous example is the assembly line and the process of mass production that appeared in the decade following commercial introduction of the automobile.[18] Mass production dramatically reduced the labor in producing parts for and assembling the automobile, but after its widespread adoption productivity gains in automobile production were much lower. A similar pattern was observed with electrification, which saw the highest productivity gains in the early decades after introduction. Many other industries show similar patterns. The pattern was again followed by the computer, information and communications industries in the late 1990s when much of the national productivity gains occurred in these industries.[19] There is a general understanding of the main determinants or drivers of productivity growth. Certain factors are critical for determining productivity growth. The Office for National Statistics (UK) identifies five drivers that interact to underlie long-term productivity performance: investment, innovation, skills, enterprise and competition.[20]

Research and development (R&D) tends to increase productivity growth,[21] with public R&D showing larger spillovers and smaller firms experiencing larger productivity gains from public R&D.[22] Individual and team productivityTechnology has enabled massive personal productivity gains—computers, spreadsheets, email, and other advances have made it possible for a knowledge worker to seemingly produce more in a day than was previously possible in a year.[23] Environmental factors such as sleep and leisure play a significant role in work productivity and received wage.[24] Drivers of productivity growth for creative and knowledge workers include improved or intensified exchange with peers or co-workers, as more productive peers have a stimulating effect on one's own productivity.[25][26] Productivity is influenced by effective supervision and job satisfaction. An effective or knowledgeable supervisor (for example a supervisor who uses the Management by objectives method) has an easier time motivating their employees to produce more in quantity and quality. An employee who has an effective supervisor, motivating them to be more productive is likely to experience a new level of job satisfaction thereby becoming a driver of productivity itself.[27] There is also considerable evidence to support improved productivity through operant conditioning reinforcement,[28] successful gamification engagement,[29] and research-based recommendations on principles and implementation guidelines for using monetary rewards effectively.[30] Detrimental impact of bullying, incivility, toxicity and psychopathyWorkplace bullying results in a loss of productivity, as measured by self-rated job performance.[31] Over time, targets of bullying will spend more time protecting themselves against harassment by bullies and less time fulfilling their duties.[32] Workplace incivility has also been associated with diminished productivity in terms of quality and quantity of work.[33] A toxic workplace is a workplace that is marked by significant drama and infighting, where personal battles often harm productivity.[34] While employees are distracted by this, they cannot devote time and attention to the achievement of business goals.[35] When toxic employees leave the workplace, it can improve the culture overall because the remaining staff become more engaged and productive.[36] The presence of a workplace psychopath may have a serious detrimental impact on productivity in an organisation.[37] In companies where the traditional hierarchy has been removed in favor of an egalitarian, team-based setup, the employees are often happier, and individual productivity is improved (as they themselves are better placed to increase the efficiency of the workfloor). Companies that have these hierarchies removed and have their employees work more in teams are called liberated companies or "Freedom Inc.'s".[38][39][40][41][42] The Kaizen system of bottom-up, continuous improvement was first practiced by Japanese manufacturers after World War II, most notably as part of The Toyota Way. Business productivityProductivity is one of the main concerns of business management and engineering. Many companies have formal programs for continuously improving productivity, such as a production assurance program. Whether they have a formal program or not, companies are constantly looking for ways to improve quality, reduce downtime and inputs of labor, materials, energy and purchased services. Often simple changes to operating methods or processes increase productivity, but the biggest gains are normally from adopting new technologies, which may require capital expenditures for new equipment, computers or software. Modern productivity science owes much to formal investigations that are associated with scientific management.[43] Although from an individual management perspective, employees may be doing their jobs well and with high levels of individual productivity, from an organizational perspective their productivity may in fact be zero or effectively negative if they are dedicated to redundant or value destroying activities.[23] In office buildings and service-centred companies, productivity is largely influenced and affected by operational byproducts—meetings.[44] The past few years have seen a positive uptick in the number of software solutions focused on improving office productivity.[45] In truth, proper planning and procedures are more likely to help than anything else.[46] Productivity paradoxOverall productivity growth was relatively slow from the 1970s through the early 1990s,[47] and again from the 2000s to 2020s. Although several possible causes for the slowdown have been proposed there is no consensus. The matter is subject to a continuing debate that has grown beyond questioning whether just computers can significantly increase productivity to whether the potential to increase productivity is becoming exhausted.[48] National productivityIn order to measure the productivity of a nation or an industry, it is necessary to operationalize the same concept of productivity as in a production unit or a company, yet, the object of modelling is substantially wider and the information more aggregate. The calculations of productivity of a nation or an industry are based on the time series of the SNA, System of National Accounts. National accounting is a system based on the recommendations of the UN (SNA 93) to measure the total production and total income of a nation and how they are used.[49] International or national productivity growth stems from a complex interaction of factors. Some of the most important immediate factors include technological change, organizational change, industry restructuring and resource reallocation, as well as economies of scale and scope. A nation's average productivity level can also be affected by the movement of resources from low-productivity to high-productivity industries and activities. Over time, other factors such as research and development and innovative effort, the development of human capital through education, and incentives from stronger competition promote the search for productivity improvements and the ability to achieve them. Ultimately, many policy, institutional and cultural factors determine a nation's success in improving productivity. At the national level, productivity growth raises living standards because more real income improves people's ability to purchase goods and services (whether they are necessities or luxuries), enjoy leisure, improve housing and education and contribute to social and environmental programs. Some have suggested that the UK's 'productivity puzzle' is an urgent issue for policy makers and businesses to address in order to sustain growth.[50] Over long periods of time, small differences in rates of productivity growth compound, like interest in a bank account, and can make an enormous difference to a society's prosperity. Nothing contributes more to reduction of poverty, to increases in leisure, and to the country's ability to finance education, public health, environment and the arts’.[51] Productivity is considered basic statistical information for many international comparisons and country performance assessments and there is strong interest in comparing them internationally. The OECD[52] publishes an annual Compendium of Productivity Indicators[53] that includes both labor and multi-factor measures of productivity. See alsoReferencesCitations

Sources

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Productivity. Wikiquote has quotations related to Productivity.

Handbooks |