|

Rokeby (poem)

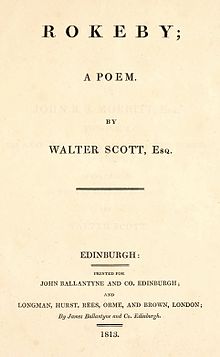

Rokeby (1813) is a narrative poem in six cantos with voluminous antiquarian notes by Walter Scott. It is set in Teesdale during the English Civil War. BackgroundThe first hint of Rokeby is found in a letter of 11 January 1811 from Scott to Lady Abercorn in which he says that although he is not currently engaged on a new poem he has 'sometimes thought of laying the scene during the great civil war in 1643'.[1] In June he was offered 3000 guineas for the poem, which had not yet been begun.[2] By 10 December he is thinking of setting the new work 'near Barnard Castle',[3] and on the 20th he writes to his friend J. B. S. Morritt, owner of Rokeby Park, that he has in mind 'a fourth romance in verse, the theme during the English civil wars of Charles I. and the scene your own domain of Rokeby', and asking for detailed local information. The proceeds of the poem will help finance building work at his new home, Abbotsford.[4] Composition seems to have started in the spring of 1812, but the first canto ran into problems. On 2 March he told Morritt that he had destroyed it 'after I had written it fair out because it did not quite please me'.[5] In the later spring he was at work again, now accompanied by the sound of the builders extending the cottage at Abbotsford.[6] In the middle of July he sent the new Canto 1 for comment by James Ballantyne and William Erskine,[7] but their verdict was unfavourable, sapping his confidence.[8] He decided to burn what he had written, having 'corrected the spirit out of it', but by 2 September he had 'resumed the pen in [his] old Cossack manner' and 'succeeded rather more to [his] own mind'.[9] Thereafter composition proceeded briskly, though at one stage Scott contemplated reducing the length to five cantos to enable publication for the Christmas market.[10] He paid Rokeby a visit in late September and early October to gather local colour.[11] The work was completed on the last day of 1812.[12] EditionsRokeby was published by John Ballantyne and Co. at Edinburgh on 11 January 1813, and at London on 15 January by Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. The price was two guineas (£2 2s or £2.10), and about 3000 copies were printed. Four further editions followed in the same year.[13] In 1830 Scott provided the poem with a new Introduction in Volume 8 of the 11-volume set of The Poetical Works.[14] A critical edition is due to be published as Volume 4 of The Edinburgh Edition of Walter Scott's Poetry by Edinburgh University Press.[15] Characters

SynopsisAt Oswald's instigation Bertram makes an attempt on the life of Philip, which he mistakenly thinks has succeeded, and an attack on Rokeby Castle, in which the castle is set on fire. Wilfrid and Matilda, through the efforts of Redmond, are able to escape the blaze. It emerges that Redmond, now in Oswald's hands, is the long-lost son of Philip, and that Philip has survived the assassination attempt. Oswald tries to force Lord Rokeby to accept a marriage between Wilfrid and Matilda, but Wilfrid's death forestalls this plan. Bertram kills his master Oswald to avoid further bloodshed, but is killed in his turn. Philip is reunited with his son, and Matilda and Redmond marry. Canto summaryCanto 1: Bertram Risingham arrives at Barnard Castle, and after informing Oswald Wycliffe that he has killed Philip Mortham, as agreed, while Philip and he were both fighting for the Parliament at Marston Moor, claims Philip's accumulated treasure as his reward. Oswald instructs his son Wilfrid, a soft lad in love with Matilda Rokeby, to accompany Bertram to Mortham Castle to secure the treasure. Canto 2: As they arrive at Mortham, Bertram, who believes he has seen Philip's ghost, inadvertently reveals to Wilfrid that he killed him, but when Wilfrid tries to arrest him he reacts violently before being stopped by the living Philip who disappears again after warning Wilfrid not to divulge his continued existence. Oswald arrives, accompanied by Rokeby's page Redmond O'Neale, who says he witnessed the murder at Marston and initiates a vain search for Bertram who has fled the scene. Oswald tells his son that Rokeby has been taken prisoner in the battle and consigned to his charge, and that though Redmond is Wilfrid's rival for Matilda's affection she may be induced to accept him to secure her father's release. Canto 3: After an arduous flight Bertram vows vengeance on Redmond, Oswald, and Wilfrid, believing that Oswald had intended to deprive him of the treasure. He encounters Guy Denzil and agrees to head a band of outlaws, including a young minstrel Edmund of Winston, quartered in a cave. Denzil tells Bertram that the treasure is in fact at Rokeby, whither Philip had moved it intending that his niece Matilda should inherit it in the event of his death in battle. Denzil and Bertram make plans to attack the castle. Canto 4: Matilda takes the air with the civilised rivals for her affections Wilfrid and Redmond: the latter had been her childhood companion after he was consigned to Rokeby's keeping because of his grandfather's destitution and physical deterioration in Ireland. For a while Rokeby had been inclined to favour a match proposed by Oswald between Matilda and Wilfrid, but he had changed his mind when Oswald defected to the Parliamentary side. Matilda tells Wilfrid and Redmond how Philip had consigned his treasure to her with a written account of his story: Oswald had failed to seduce his wife and in revenge had managed matters so that Oswald should kill her on suspicion of infidelity. Soon afterwards Philip's infant son had been abducted by armed men. After a career of piracy in South America Philip had returned, accompanied by Bertram, seeking vengeance and his son. After renouncing vengeance on religious grounds, he had entrusted the treasure to Matilda's keeping. Wilfrid and Redmond agree to convey Matilda to her captive father in Barnard Castle, transferring the treasure from Rokeby at the same time. Canto 5: Matilda, with Wilfrid and Redmond at Rokeby, admits the minstrel Edmund who opens the postern for Bertram and his robber band. The castle is set alight: Matilda, Redmond, the injured Wilfrid, and separately Bertram escape the conflagration. Canto 6: Three days later, Edmund returns to the robber cave and unearths a small casket with gold artefacts. He is interrupted by Bertram and tells him how Denzil and he, taken captive after the conflagration, had agreed with Oswald to save their lives by making a statement that Rokeby had enlisted their aid to storm Barnard Castle. Oswald had received a letter from Philip asking for the return of his son; Denzil announced that that son was Redmond, who had been abducted to Ireland as an infant by his grandfather O'Neale and brought back as a young man to be Rokeby's page, along with the artefacts which fell into Denzil's thieving hands, and which included an account engraved on gold tablets. Oswald has sent Edmund to retrieve the artefacts. Edmund tells Bertram that he intends to convey the artefacts to Philip and inform him that Redmond is his son. Bertram, moved, sends Edmund to tell Philip of his repentance, and ask him to lead forces to help Redmond. Oswald has Denzil executed and prepares to put pressure on Matilda to marry Wilfrid by readying the ruined church of Egliston for the beheading of her father and Redmond. Matilda agrees, but Wilfrid dies of his wounds. Oswald commands the executions to proceed, but Bertram rides into the church and shoots him dead before himself being killed by Oswald's men. Matilda and Redmond marry. ReceptionRokeby was judged Scott's best poem to date by several reviewers.[16] In particular the newly developed character interest was generally welcomed, and there was praise for the vigorous and well-conducted story and for the work's moral beauty. Sales were initially promising. J. G. Lockhart reported that bookshops in Oxford were besieged by customers wanting to read the poem, and bets were placed as to whether Rokeby would outsell Byron's recent Childe Harold's Pilgrimage. Byron himself wrote urgently from Italy asking his publisher John Murray to send him a copy.[17] In the event Rokeby sold ten thousand copies in the first three months.[18] Thomas Moore sarcastically wrote that Scott's works were turning into a picturesque tour of Britain's stately homes.[19] Lockhart, writing after Scott's death, admired the scenery of Rokeby, and found many thrilling episodes and lines scattered through the poem; he attributed its disappointing sales to the inevitable comparisons drawn by the public with Childe Harold’s greater raciness and romantic glamour.[20] In the 20th century John Buchan thought the plot too intricate for a poem. Comparing Rokeby with Scott's earlier works he found the landscape not as beguiling, but the character-drawing more subtle, and the songs superior to all of his former lyrics.[21] Andrew Lang also admired the songs, but considered the poem as a whole inferior to its predecessors, and, in common with other critics, thought the story better suited for a novel.[22][23] In Edgar Johnson's opinion the structure of the poem was strikingly innovative, but beyond Scott's powers at that date to bring off wholly successfully.[24] A. N. Wilson noted that most readers today think of it as a failure. He himself, while agreeing that it fell below the standard of vintage Scott, thought it worth re-reading.[25] Rokeby in other mediaOver a hundred musical adaptations or settings of lines from Rokeby are known. These include several songs and glees by John Clarke Whitfield, a song by William Hawes, an opera called Rokeby Castle by William Reeve, and a projected opera by Glinka from which only one song survives.[26][27] The actor-manager William Macready wrote, produced and starred in a stage version of Rokeby in 1814. Another adaptation by George John Bennett, a five-act play called Retribution, or Love's Trials, was produced at Sadler's Wells in 1850.[28][29] The artist J. M. W. Turner produced a watercolour of the river Greta at Rokeby in 1822, which had been commissioned from him as an illustration to Scott's poem.[30] The unincorporated area of Rokeby, Nebraska, is believed to be named after the poem.[31] Notes

Sources

External links |

||||||||||||||||