|

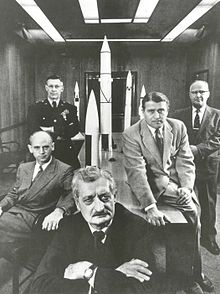

Robert Lusser Robert Lusser (19 April 1899 – 19 January 1969) was a German engineer, aircraft designer and aviator. He is remembered both for several well-known Messerschmitt and Heinkel designs during World War II, and after the war for his theoretical study of the reliability of complex systems. In the post-war era, Lusser also pioneered the development of modern ski bindings, introducing the first teflon anti-friction pads to improve release. BiographyLusser was born in Ulm. As a pilot, he won the International Light Aircraft Contest in France in 1928. Next he participated in three out of four FAI International Tourist Plane Contests, flying Klemm aircraft, and completed all three taking quite high places (Challenge 1929: 4th, Challenge 1930: 13th, and Challenge 1932: 10th).[1] In August 1930 he was 3rd in the handicapped race Giro Aereo d'Italia in Italy.[2] Lusser's first jobs were with the Klemm and Heinkel companies, before joining the newly relaunched Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (Bavarian Aircraft Works) in 1933. There, he assisted Willy Messerschmitt with his design for a touring aircraft, the Messerschmitt M37. This was later put into production as the Messerschmitt Bf 108, and formed the basis for the company's best known product, the Bf 109 fighter aircraft. By 1934, Lusser was head of Messerschmitt's design bureau and in charge of the Bf 110 heavy fighter project. In 1938 the company was renamed Messerschmitt. Lusser stayed with the company until 1938, when he returned to Heinkel. There, he led the design of two highly sophisticated aircraft that never reached their full potential - the He 280 and the He 219. The He 280 was the first jet fighter to leave the drawing board, but which the RLM (Reichsluftfahrtministerium - "Reich Aviation Ministry") passed over in favour of the Messerschmitt Me 262. The He 219 was an advanced night-fighter design that was rejected by the RLM in August 1941 as being too complex to order into production because of its many innovations. Ernst Heinkel immediately dismissed Lusser and resubmitted a simplified design that eventually saw limited production. From Heinkel, Lusser went to Fieseler, and there became involved with the company's efforts to produce a pilotless aircraft, initially designated the Fi 103. This was a collaborative effort between the company and engine manufacturer Argus, who were developing a pulsejet. Lusser worked with Argus engineer Fritz Gosslau to refine the design. The project was an initiative of the two companies, begun by Argus as early as 1934, and received little official interest until Erhard Milch recognised its potential in 1942 and assigned it high priority. Nazi propaganda dubbed this flying bomb the V1, (Vergeltungswaffe - "revenge weapon"). It was a design competing with Wernher von Braun' s "V2" vertical takeoff rocket. Despite initial demonstrations before Luftwaffe made the V2 look more reliable, it was decided both designs should proceed into production. Lusser and von Braun were rivals, and even later their relationship was never frictionless. Near Wolfsburg, Lusser found the main design flaw of his rocket, which turned out to be an underdimensioned main wing spar, as the ramp up of production began. From there on, the design worked. Post war timeLike many important German engineers, Lusser was brought to the United States after the end of World War II. There, he worked for the Navy, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and in 1953, re-joined von Braun's rocketry team at Huntsville, Alabama. During his six years there, he formalised his theories of reliability, which focus on the contribution that the reliability of each part makes to the reliability of an overall system. This is now known as Lusser's Law. Based on these calculations, he pronounced that von Braun's ambitions of reaching the Moon and Mars were doomed to failure because of the complexity of the spacecraft required. He returned to Germany, and to the Messerschmitt company, by then, Messerschmitt-Bölkow. His alarming reliability study of the adaptations that the company was making to the F-104 Starfighter that it was building under licence turned out to be tragically correct. In 1961 he ruptured his Achilles tendon while testing his ski's cable bindings in his hotel room at Saas-Fee. He decided to attack the binding problem, developing the first bindings that gripped the toe of the boot, rather than the flange projecting from the front of the sole at the toe. This allowed the toe binding to release in any direction. In 1963 he quit his job at Messerschmitt to start the Lusser Binding Company.[3] This was a major brand until his death in 1969. He died on 19 January 1969 in Munich. References

External links |