|

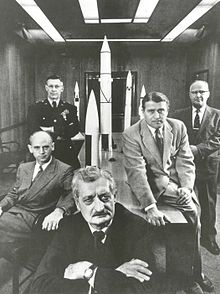

Hermann Oberth

Hermann Julius Oberth (German: [ˈhɛrman ˈjuːli̯ʊs ˈoːbɛrt]; 25 June 1894 – 28 December 1989) was an Austro-Hungarian-born German physicist and rocket pioneer of Transylvanian Saxon descent.[3] Oberth supported Nazi Germany's war effort and received the War Merit Cross (1st Class) in 1943.[5] Early life Oberth was born into a Transylvanian Saxon family in Nagyszeben (Hermannstadt), Kingdom of Hungary (today Sibiu in Romania);[6] and besides his native German, he was fluent in Hungarian and Romanian as well. At the age of 11, Oberth's interest in rocketry was sparked by the novels of Jules Verne, especially From the Earth to the Moon and Around the Moon. He was fond of reading them over and over until they were engraved in his memory.[7] As a result, Oberth constructed his first model rocket as a school student at the age of 14. In his youthful experiments, he arrived independently at the concept of the multistage rocket. During this time, however, he lacked the resources to put his ideas into practice. In 1912, Oberth began studying medicine in Munich, Germany, but after World War I broke out, he was drafted into the Imperial German Army, assigned to an infantry battalion, and sent to the Eastern Front against Russia. In 1915, Oberth was moved into a medical unit at a hospital in Segesvár (German: Schäßburg; Romanian: Sighișoara), Transylvania, in Austria-Hungary (today Romania).[8] There he found the spare time to conduct a series of experiments concerning weightlessness, and later resumed his rocketry designs. By 1917, he showed designs of a missile using liquid propellant with a range of 290 km (180 mi) to Hermann von Stein, the Prussian Minister of War.[9] On 6 July 1918, Oberth married Mathilde Hummel, with whom he had four children. Among Oberth's children, one lost his life as a soldier during World War II. His daughter, Ilse (born 1924), died on August 28, 1944, in an accidental explosion at the Redl-Zipf V-2 rocket engine test facility and liquid oxygen plant where she worked as a rocket technician. In 1919, Oberth once again moved to Germany, this time to study physics, initially in Munich and later at the University of Göttingen. In 1922, Oberth's proposed doctoral dissertation on rocket science was rejected as "utopian". However, professor Augustin Maior of the University of Cluj in Romania offered Oberth the opportunity to defend his original dissertation there in order to receive a doctorate.[10] He did so successfully on 23 May 1923.[8] He next had his 92-page work published privately in June 1923 as the somewhat controversial book, Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen[11] (The Rocket into Planetary Space).[12] By 1929, Oberth had expanded this work to a 429-page book titled Wege zur Raumschiffahrt (Ways to Spaceflight).[13] Oberth commented later that he made the deliberate choice not to write another doctoral dissertation. He wrote, "I refrained from writing another one, thinking to myself: Never mind, I will prove that I am able to become a greater scientist than some of you, even without the title of Doctor."[14] Oberth criticized the German system of education, saying "Our educational system is like an automobile which has strong rear lights, brightly illuminating the past. But looking forward, things are barely discernible."[14] Oberth became in 1927 a member of the Verein für Raumschiffahrt (VfR) – the "Spaceflight Society" – an amateur rocketry group that had taken great inspiration from his book, and Oberth acted as something of a mentor to the enthusiasts who joined the Society, which included persons such as Wernher von Braun, Rolf Engel, Rudolf Nebel or Paul Ehmayr. Oberth lacked the opportunities to work or to teach at the college or university level, as did many well-educated experts in the physical sciences and engineering in the time period of the 1920s through the 1930s – with the situation becoming much worse during the worldwide Great Depression that started in 1929. Therefore, from 1924 through 1938, Oberth supported himself and his family by teaching physics and mathematics at the Stephan Ludwig Roth High School in Mediaș, Romania.[8] Rocketry and spaceflightDuring portions of 1928 and 1929, Oberth served as a scientific advisor in Berlin for the film "Frau im Mond" ("The Woman in the Moon"). This pioneering film was directed and produced by the renowned filmmaker Fritz Lang, in collaboration with the Universum Film AG company. The film was of enormous value in popularizing the ideas of rocketry and space exploration. One of Oberth's main assignments was to build and launch a rocket as a publicity event just before the film's premiere. He also designed the model of the Friede, the main rocket portrayed in the film. On June 5, 1929, Oberth won the inaugural Prix REP-Hirsch (REP-Hirsch Award) from the French Astronomical Society. This honor recognized his significant contributions to the field of astronautics and interplanetary travel, specifically highlighted in his book Wege zur Raumschiffahrt[13] ("Ways to Spaceflight"). The book, an expanded version of Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen ("The Rocket to Interplanetary Space"), secured his position as a prominent figure in the field.[15] The volume is dedicated to Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou.[13]  Oberth's student Max Valier joined forces with Fritz von Opel to create the world's first large-scale experimental rocket program Opel-RAK, leading to speed records for ground and rail vehicles and the world's first rocket plane. Opel RAK.1, a purpose-built design by Julius Hatry,[16] was demonstrated to the public and world media on September 30, 1929, piloted by von Opel. Valier's and von Opel's demonstrations had a strong and long-lasting impact on later spaceflight pioneers, in particular on another of Oberth's students, Wernher von Braun. Shortly after the Opel RAK team's successful liquid-fuel rocket launches of April 10 and 12, 1929 by Friedrich Wilhelm Sander at Opel Rennbahn in Rüsselsheim, Oberth conducted in the autumn of 1929 a static firing of his first liquid-fueled rocket motor, which he named the Kegeldüse. The engine was built by Klaus Riedel in a workshop space provided by the Reich Institution of Chemical Technology, and although it lacked a cooling system, it did run briefly.[17] He was helped in this experiment by an 18-year-old student Wernher von Braun, who would later become a giant in both German and American rocket engineering from the 1940s onward, culminating with the gigantic Saturn V rockets that made it possible for man to land on the Moon in 1969 and in several following years. Indeed, Von Braun said of him:

Basic research and technical draftsThe rocket in spaceflight In 1923, Oberth's book The Rocket to the Planetary Spaces was published.[11] This publication is generally regarded as a kind of initial spark for rocket and space travel enthusiasm in Germany. Many later rocket engineers were inspired by his precise and comprehensive theoretical considerations and his bold conclusions.[18] The work sparked heated debates, known at the time as the Battle of the Many Formulas. The second edition appeared in 1925, and it was also sold out after a short time.[19] In his book, Oberth puts forward the following theses:

With the launch of Sputnik (1957) and the flight of Yuri Gagarin (1961) into space, these ideas, which were still completely utopian at the beginning of the 1920s, became a reality less than four decades later. Marsha Freeman writes, "The rockets were only a means to an end, his goal was space travel."[20] Oberth thought of interplanetary space travel, of a multiplanetary humanity. In his first book in 1923 he gives the first "outlook": He goes into more detail on physical and physical-chemical, as well as physiological experiments in weightless space, on the space telescope, research into the solar corona, the space station for Earth observation and the space mirror in Earth orbit for influencing the weather[11] The third, greatly expanded edition of his first book was published by Oberth in 1929 with the new title Ways to Spaceflight.[13] In the years that followed, the book became the standard work for space exploration and rocket technology and was called the "Bible of scientific astronautics" by the French aviation and rocket pioneer Robert Esnault-Pelterie.[19]: 117 In this book, Oberth describes possible uses of his two-stage rocket, among other things on pages 285 to 333 the crewed space flight including space suit for external use, the space telescope for Earth observation and the duration of interplanetary flights, on pages 333 to 350 his ideas and the theoretical basis for space stations in near Earth orbit from 700 to 1200 km above the ground for Earth and weather observation and as a starting point for flights to the Moon and to the planets, on pages 336 to 351 he explains the construction and function of the space mirror[11][13] he invented in 1923 with 100 bis 300 km in diameter in Earth orbit, with which, among other things, the weather is to be influenced in a targeted regional manner or the solar radiation is to be weakened in a targeted regional manner. On pages 350 to 386 in the chapter "Journeys to Strange Worlds", Hermann Oberth presents his scientific considerations and calculations for flights (including landings) to the Moon, to asteroids, to Mars, to Venus, to Mercury and to comets. Space MirrorIn 1923, Oberth initially outlined the concept of his space mirrors in his book Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (The Rocket to Interplanetary Space). These mirrors, with diameters ranging from 100 to 300 km, were envisioned to be composed of a grid network consisting of individually adjustable facets. Oberth's concept of space mirrors in orbit around the Earth serves the purpose of focusing sunlight on specific regions of the planet's surface or redirecting it into space. This approach differs from creating shaded areas at the Lagrange point between the Earth and the Sun, as it does not involve diminishing solar radiation across the entire exposed surface. According to Oberth, these colossal orbital mirrors possess the potential to illuminate individual cities, safeguard against natural disasters, manipulate weather patterns and climate, and even create additional living space for billions of people. He places significant emphasis on their capacity to influence the trajectories of barometric high and low-pressure areas. However, it is important to acknowledge that the implementation of such climate engineering interventions, including space mirrors, requires further extensive research before their practical applicability can be fully realized. Further publications followed in which he took into account the technical progress achieved up to that point: Ways to Spaceflight (1929), Menschen im Weltraum. Neue Projekte für Raketen-und Raumfahrt (People in Space. New Projects for Rocket and Space, 1957), and Der Weltraumspiegel (The Space Mirror, 1978). To optimize costs, Oberth's concept proposes the utilization of lunar minerals for producing components on the Moon. The Moon's lower gravitational pull necessitates less energy for launching these components into lunar orbit. Additionally, the Earth's atmosphere is spared the burden of numerous rocket launches. The envisioned process involves launching the components from the lunar surface into lunar orbit using an electromagnetic lunar slingshot, subsequently "stacking" them at a 60° libration point. These components could then be transported into orbit via electric spaceships, designed by Oberth with minimal recoil. Once in orbit, the components would be assembled into mirrors with diameters ranging from 100 to 300 km. Oberth's estimate in 1978 suggested that the realization of this concept could occur between 2018 and 2038. Oberth emphasized that these mirrors could potentially serve as weapons. Given this aspect, coupled with the complexity of the project, the realization of these mirrors would only be feasible as a peace initiative undertaken by humanity.[11][13]: pp. 87–88 [21][22][23] In 2023, the space mirror devised by Oberth is categorized within the field of Climate Engineering, specifically under Solar Radiation Management (SRM) as a subset of Space-Mirrors. The associated risks of these deliberate interventions in weather and climate are also examined and deliberated upon within this classification. The Moon CarHermann Oberth published his concept of a moving and jumping lunar vehicle for future, extensive lunar exploration in 1953.[24][25] In his considerations, he assumed that large distances should be covered quickly and that extensive fissures/ravines or impassable terrain that block the way should be overcome so that large detours can be avoided. The vehicle, which would weigh about 10000 kg on Earth and only 1654 kg on the Moon due to the weak gravitational pull, would be built on Earth, transported to the Moon and dropped on the lunar surface. The tower-like structure has only one leg and it stands on a tracked chassis with a footprint of 2.5 m x 2.5 m. A motor with 51.5 kW of power is sufficient to drive at a speed of up to 150 km/h, depending on the terrain. The required energy in the form of electrical current is supplied by the solar power plant above the crew cabin and the gyroscope. The leg is a gas-tight cylinder in which the 4.5 m long "jumping leg" can move up and down like a piston in a shock absorber and can be extended and retracted for jumping. The powerful gyroscope above the crew cabin keeps the vehicle vertical and ensures that the vehicle can never tilt more than 45 degrees. The jumps could be up to 125 m high and several 100 m wide. Jumping would occur if the vehicle had to overcome an impassable area or fissures/ravines, or if it had to get from a higher location (e.g. a mountain terrace) to a lower location or vice versa.[26] Oberth writes: "I wanted to present my readers not just with a rough sketch of the lunar car, but with drawings and descriptions based on precise calculations and designs. So I racked my brains over hundreds of details, calculated, compared, constructed, rejected and re-planned until the design was such that I could present it with a clear conscience. Now I can say: I am sure that my moon car can be built." Feasibility studies or development work on Oberth's lunar vehicle have not begun until 2023 because there are no concrete plans for lunar exploration in which such a large vehicle could be used. Ion propulsion for interplanetary spaceflightThe principle of ion propulsion was first presented in 1929 by the space pioneer Hermann Oberth in his work Ways to Spaceflight,[13] which is referred to as the "Bible of Space Technology",[19]: 117 in which he describes for the first time the physics, the function, the construction and the use for the interplanetary flight of an ion engine on pages 386 to 399. Oberth also presented at the 12th Rocket and Space Conference of the Deutsche Raketen-Gesellschaft (DRG) (German Rocket Society) in September 1963 in Hamburg, FRG a new idea for the electric spaceship.[27] Quote: "My proposal concerns an electric spaceship that does not emit ions and electrons, but rather nebula droplets that are 1,000 to 100,000 times larger in size depending on the project and to form an ion or electron as a condensation nucleus." Tasks in World War IIFrom 1923 to 1938 Oberth worked with short breaks in 1929 and 1930 as a high school teacher for physics and mathematics in his home country Transylvania in Romania.[19] The Romanian Hermann Oberth, known worldwide in the professional world, with his many foreign contacts, was regarded as a security risk for the secrecy of the development work on Aggregate 4 in Peenemünde. Therefore, from June 1938 he was employed / sidelined from June 1938 by means of a two-year research contract with the German Research Institute for Aviation (DVL) at the Vienna University of Technology and then from July 1940 at the University of Technology Dresden in the Greater German Reich.[28] When he wanted to return to Transylvania in May 1941, he received German citizenship and was conscripted in August 1941 under the alias "Friedrich Hann"[29]: 58 to the Army Research Institute Peenemünde, where the world's first large rocket, the Aggregat 4 - later called "Vergeltungswaffe V2" - was developed under the direction of Wernher von Braun. Oberth was not involved in this work,[29]: 58 [18]: 150 [28]: 157–164 [30]: 101 but placed in the patent review,[31]: 144 [18]: 94 and wrote various reports, for example "About the best outline of multi-stage rockets" and about "Defense against enemy planes with large, remote-controlled solid missile".[31][18] (Oberth criticized the V2 design because, in his view, it was too complicated and too expensive for military purposes. He would have developed a solid fuel rocket for the V2's intended purposes.)[19] Around September 1943, he was awarded the Kriegsverdienstkreuz I Klasse mit Schwertern (War Merit Cross 1st Class, with Swords) for his "outstanding, courageous behavior ... during the attack" on 17./18. Aug 1943 on Peenemünde by Operation Hydra, part of Allied operations against the German rocket programme.[5] In December 1943 Oberth asked for his transfer[30]: 101 to WASAG in Reinsdorf near Wittenberg/FRG to develop the anti-aircraft solid missile recommended by him. He fled from there in April 1945, had to go to two different US internment camps, was released in August 1945 as a "person unaffected by the Nazi era" and came to live with his family in Feucht (Middle Franconia) FRG,[19][20][18] where his family had already moved in 1943.[19] Feucht is located near the regional capital of Nuremberg, which became part of the American Zone of occupied Germany, and also the location of the high-level war-crimes trials of the surviving Nazi leaders. Post-war period Oberth was not involved in the American "Project Paperclip" because he was not involved in the development of the Aggregat 4 - later called "Vergeltungswaffe V2". For Oberth there was no employment in Germany either as a teacher of physics or mathematics or as a scientist. That is why Hermann Oberth went to Switzerland in 1948 and worked there both as a scientific consultant and as an author for the specialist journal Interavia. In the years 1950 to 1953 he was in the service of the Italian Navy and developed a solid fuel rocket. In 1953, Oberth returned to Feucht, Germany, to publish his book Menschen im Weltraum (Man into Space), in which he described his ideas for space-based reflecting telescopes, space stations, electric-powered spaceships, and space suits. Oberth eventually worked from 1955 for his former assistant Wernher von Braun, who was developing space rockets for NASA in Huntsville, Alabama. Among other things, Oberth was involved in preparing the study "The Development of Space Technology in the Next Ten Years". In 1958, Oberth returned to Feucht, Germany, where he published his ideas for a lunar exploration vehicle, a "moon catapult", and "damped" helicopters and airplanes. In 1961, Oberth returned to the United States, where he worked for the Convair Corporation as a technical consultant for the Atlas missile program. He retired in 1962.[31][20][28][19] During the 1950s and 1960s, Oberth offered his opinions regarding unidentified flying objects (UFOs). He was a supporter of the extraterrestrial hypothesis for the origin of the UFOs that were seen from Earth. For example, in an article in The American Weekly magazine of 24 October 1954, Oberth stated: "It is my thesis that flying saucers are real, and that they are space ships from another solar system. I think that they possibly are manned by intelligent observers who are members of a race that may have been investigating our earth for centuries".[32] He also published in the second edition of Flying Saucer Review, an article titled, "They Come From Outer Space". He discussed the history of reports of "strange luminous objects" in the sky, mentioning that the earliest historical case is of "Shining Shields" reported by Pliny the Elder. He wrote, "Having weighed all the pros and cons, I find the explanation of flying discs from outer space the most likely one. I call this the "Uraniden" hypothesis, because from our viewpoint the hypothetical beings appear to come from the sky (Greek – 'Uranos')."[33] Later life Oberth retired in 1962 at the age of 68. From 1965 to 1967 he was a member of the National Democratic Party of Germany, which was considered to be far right. In July 1969, Oberth returned to the United States to witness the launch of the Apollo project Saturn V rocket from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida that carried the Apollo 11 crew on the first landing mission to the Moon.[34] The 1973 oil crisis inspired Oberth to look into alternative energy sources, including a plan for a wind power station that could utilize the jet stream. However, his primary interest during his retirement years was to turn to more abstract philosophical questions. Most notable among his several books from this period is Primer For Those Who Would Govern. Oberth returned to the United States to view the launch of STS-61-A, the Space Shuttle Challenger launched 30 October 1985. Oberth died in Nuremberg, West Germany, on 28 December 1989, just shortly after the fall of the Iron Curtain.[9][35] Oberth was described as a "loyal supporter and donor" by Stille Hilfe, a Nazi support organisation, in its obituary of him.[36] Awards and honors

List from the Oberth biography by Hans Barth[19]

LegacyHermann Oberth is memorialized by the Hermann Oberth Space Travel Museum in Feucht, Germany, and by the Hermann Oberth Society. The museum brings together scientists, researchers, engineers, and astronauts from the East and the West to carry on his work in rocketry and space exploration. In 1980, Oberth was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum.[41] The Danish Astronautical Society has named Hermann Oberth an honorary member.[42] In Romania, the Faculty of Engineering of Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu is named after him.[43] In 1994, a memorial house was established in Mediaș on the 100th anniversary of his birth. It exhibits various items related to rocket technology and space travel, and also has an audio-video room for documentary films.[44] He discovered the Oberth effect (powered flyby or Oberth maneuver), a fuel-saving strategy for interplanetary space flight that is commonly used today. There are also a crater on the Moon and asteroid 9253 Oberth named after him. In Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, the USS Grissom was classified as an Oberth-class starship. Several other Oberth-class starships also appeared in subsequent Star Trek films and television series. Books

See also

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||